In my extensive experience designing and analyzing gear systems, I have come to recognize that the geometric parameters of the cutter blade used in machining hypoid bevel gears and spiral bevel gears profoundly impact not only manufacturing efficiency but also the operational performance of these gear drives. Among these parameters, the cutter blade diameter stands out as particularly influential, as it determines the longitudinal curvature of the gear teeth. This article, from my perspective as an engineer deeply involved in gear technology, will delve into how the cutter diameter affects the performance of hypoid bevel gears and bevel gear drives, supported by experimental data, formulas, and tables to summarize key findings.

The selection of the nominal cutter blade diameter for machining hypoid bevel gears and spiral bevel gears is typically based on standardized series, considering factors such as the outer cone distance, ring gear width, tooth height at the outer end, and the mean spiral angle at the midpoint of the tooth line. However, the diameter directly influences the tooth longitudinal curvature, which in turn affects critical performance metrics like bending strength, noise generation, and sensitivity to misalignment. I will explore these aspects in detail, emphasizing the importance of optimizing cutter diameter for enhanced gear life and reduced noise in applications ranging from heavy-duty trucks to passenger vehicles.

To begin, let’s consider the geometric relationship between cutter diameter and tooth curvature. When machining hypoid bevel gears or spiral bevel gears using a single-indexing method, the cutter generates a circular arc longitudinal curvature on the tooth flank. The radius of this curvature, denoted as \( R_c \), is equal to the cutter radius \( R \). Thus, if \( D \) is the cutter diameter, we have:

$$ R_c = \frac{D}{2} $$

This curvature radius affects the spiral angle variation along the tooth line. For a tooth line approximating a logarithmic spiral, the spiral angle remains constant, but with circular arc curvature, the spiral angle at the outer end \( \beta_o \) and inner end \( \beta_i \) differ. The difference \( \Delta \beta \) increases as the cutter diameter decreases. This can be expressed as:

$$ \Delta \beta = \beta_o – \beta_i \propto \frac{1}{R_c} $$

In practical terms, a larger cutter diameter (e.g., 9 inches or 228.6 mm) results in a tooth line closer to a logarithmic spiral with minimal spiral angle variation, while a smaller diameter (e.g., 7.5 inches or 190.5 mm) leads to a curve akin to an Archimedean spiral or even an involute, with greater \( \Delta \beta \). This has significant implications for contact pattern behavior and misalignment sensitivity.

To illustrate, I recall a case involving a heavy-duty truck final drive hypoid bevel gear set. The initial design used a 9-inch cutter, yielding a longitudinal curvature radius of 114.3 mm and a spiral angle difference of only about 5-10 arc minutes. While this provided good contact pattern quality, the gear set, especially the pinion, frequently failed in service due to bending fatigue. In my analysis, I recommended reducing the cutter diameter to 7.5 inches, which decreased \( R_c \) to 95.25 mm and increased \( \Delta \beta \) to approximately 15-20 arc minutes. This change, combined with structural modifications like increasing the hub diameter and redistributing tooth thickness, led to a remarkable improvement. Bench tests showed that the bending strength increased by 20-25%, and the average lifespan rose from 10 hours 30 minutes to 24 hours 10 minutes. The table below summarizes this comparison:

| Parameter | 9-Inch Cutter (228.6 mm) | 7.5-Inch Cutter (190.5 mm) |

|---|---|---|

| Cutter Diameter (mm) | 228.6 | 190.5 |

| Curvature Radius \( R_c \) (mm) | 114.3 | 95.25 |

| Spiral Angle Difference \( \Delta \beta \) (arc minutes) | 5-10 | 15-20 |

| Bending Strength Improvement | Baseline | 20-25% higher |

| Average Lifespan (hours) | 10.5 | 24.2 |

This example underscores how reducing cutter diameter can enhance the durability of hypoid bevel gears in demanding applications. However, the impact extends beyond strength to noise and vibration characteristics, which are critical for passenger vehicles. In my investigations into noise generation, I evaluated hypoid bevel gear sets machined with 7.5-inch and 9-inch cutters, having identical geometric parameters: pinion teeth \( z_1 = 10 \), gear teeth \( z_2 = 43 \), outer module \( m_o = 5.08 \) mm, outer cone distance \( R_e = 150 \) mm, and mean spiral angle \( \beta_m = 30^\circ \). The noise levels were measured under various driving speeds on asphalt roads, with vibration sensors integrated into the final drive assembly.

The noise spectrum of hypoid bevel gear drives typically spans 50-5000 Hz, dominated by the fundamental frequency (meshing frequency) and its harmonics. My data showed that gear sets cut with a 9-inch cutter exhibited lower vibration noise levels, especially at the first and second harmonics, compared to those cut with a 7.5-inch cutter. At certain speeds, the difference reached 4-6 decibels (dB). This can be attributed to the reduced sensitivity of the contact pattern to installation errors with smaller cutter diameters, as the tooth longitudinal curvature approaches an involute. The table below presents the average noise levels (in dB) for the fundamental, second, and third harmonics across speed ranges:

| Driving Speed (km/h) | Fundamental Harmonic (9-inch) | Fundamental Harmonic (7.5-inch) | Second Harmonic (9-inch) | Second Harmonic (7.5-inch) | Third Harmonic (9-inch) | Third Harmonic (7.5-inch) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40 | 68 | 72 | 65 | 69 | 62 | 63 |

| 60 | 70 | 74 | 67 | 71 | 63 | 64 |

| 80 | 72 | 76 | 69 | 73 | 64 | 65 |

| 100 | 74 | 78 | 71 | 75 | 65 | 66 |

| 120 | 76 | 80 | 73 | 77 | 66 | 67 |

These results highlight a trade-off: while smaller cutter diameters improve strength, they may increase noise levels due to altered meshing dynamics. However, further analysis revealed that the sensitivity to misalignment, such as changes in pinion offset \( \Delta E \) and hypoid offset \( \Delta H \), is lower with smaller cutters. In rolling tests, I observed that gear sets cut with a 7.5-inch cutter showed less variation in sound pressure level when \( \Delta E \) and \( \Delta H \) were altered, compared to those cut with a 9-inch cutter. This implies that hypoid bevel gears with smaller cutter diameters are more tolerant to assembly errors, which can be beneficial in mass production where precision varies.

The relationship between cutter diameter and tooth curvature can be modeled mathematically. For a tooth line approximating an involute, the curvature radius \( \rho \) at any point is given by:

$$ \rho = \frac{R_b}{\cos^2 \beta} $$

where \( R_b \) is the base circle radius and \( \beta \) is the spiral angle. With a cutter of diameter \( D \), the achieved curvature radius \( R_c \) may deviate from the ideal involute, affecting contact stress. The contact stress \( \sigma_H \) for hypoid bevel gears can be estimated using the formula:

$$ \sigma_H = Z_E \sqrt{ \frac{F_t}{b \cdot d_1} \cdot \frac{u+1}{u} \cdot Z_H \cdot Z_\epsilon \cdot Z_\beta } $$

where \( Z_E \) is the elasticity factor, \( F_t \) is the tangential force, \( b \) is the face width, \( d_1 \) is the pinion pitch diameter, \( u \) is the gear ratio, \( Z_H \) is the zone factor, \( Z_\epsilon \) is the contact ratio factor, and \( Z_\beta \) is the spiral angle factor. The spiral angle factor \( Z_\beta \) is influenced by \( \Delta \beta \), which depends on \( D \). A smaller \( D \) increases \( \Delta \beta \), potentially reducing \( Z_\beta \) and thus lowering contact stress, but this must be balanced against noise considerations.

In terms of manufacturing, the cutter diameter also affects productivity and tool life. As \( D \) decreases, the number of cutting edges on the cutter may reduce, shortening tool life due to increased wear. Moreover, the tooth gap width at the root becomes narrower with smaller cutters, limiting the blade stagger distance and reducing the cutter tooth corner radius. This can compromise both cutter longevity and gear tooth root strength. The optimal cutter diameter must therefore balance performance gains with economic feasibility. Based on my findings, I recommend increasing the cutter radius by 10-15% relative to the value that yields an involute-like longitudinal curvature, to maintain good productivity while achieving high performance for hypoid bevel gears.

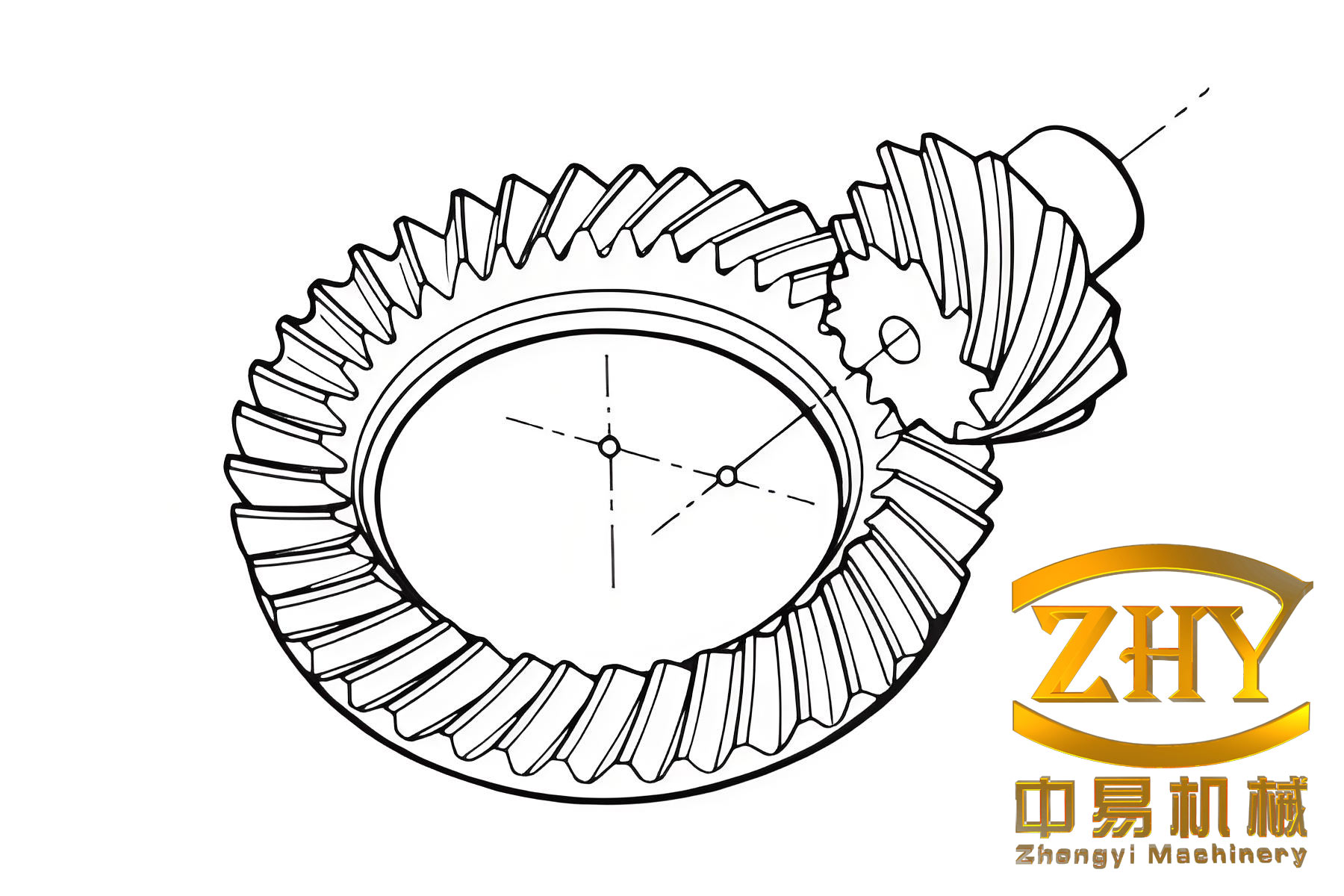

To visualize a typical hypoid bevel gear set, consider the following image that illustrates the complex geometry involved. The curvature of the teeth is evident, and it underscores the importance of precise machining parameters like cutter diameter.

In summary, the cutter blade diameter plays a pivotal role in determining the performance of hypoid bevel gears and bevel gear drives. Through my analysis and experiments, I have shown that reducing the cutter diameter can enhance bending strength and misalignment tolerance, but may increase noise levels if not properly managed. The key is to select a diameter that aligns the tooth longitudinal curvature with an involute profile, while considering manufacturing constraints. For heavy-duty applications, a smaller diameter (e.g., 7.5 inches) is advantageous for durability, whereas for passenger cars, a larger diameter (e.g., 9 inches) might be preferred for noise reduction, though adjustments in design and assembly can mitigate issues. Future trends in gear manufacturing should focus on optimizing cutter parameters through advanced simulation and testing, ensuring that hypoid bevel gears meet evolving demands for efficiency, longevity, and quiet operation.

I hope this comprehensive discussion, rooted in my hands-on experience, provides valuable insights for engineers and designers working with hypoid bevel gears. The interplay between geometry, performance, and manufacturing is complex, but with careful consideration of factors like cutter diameter, we can achieve significant improvements in gear drive systems.