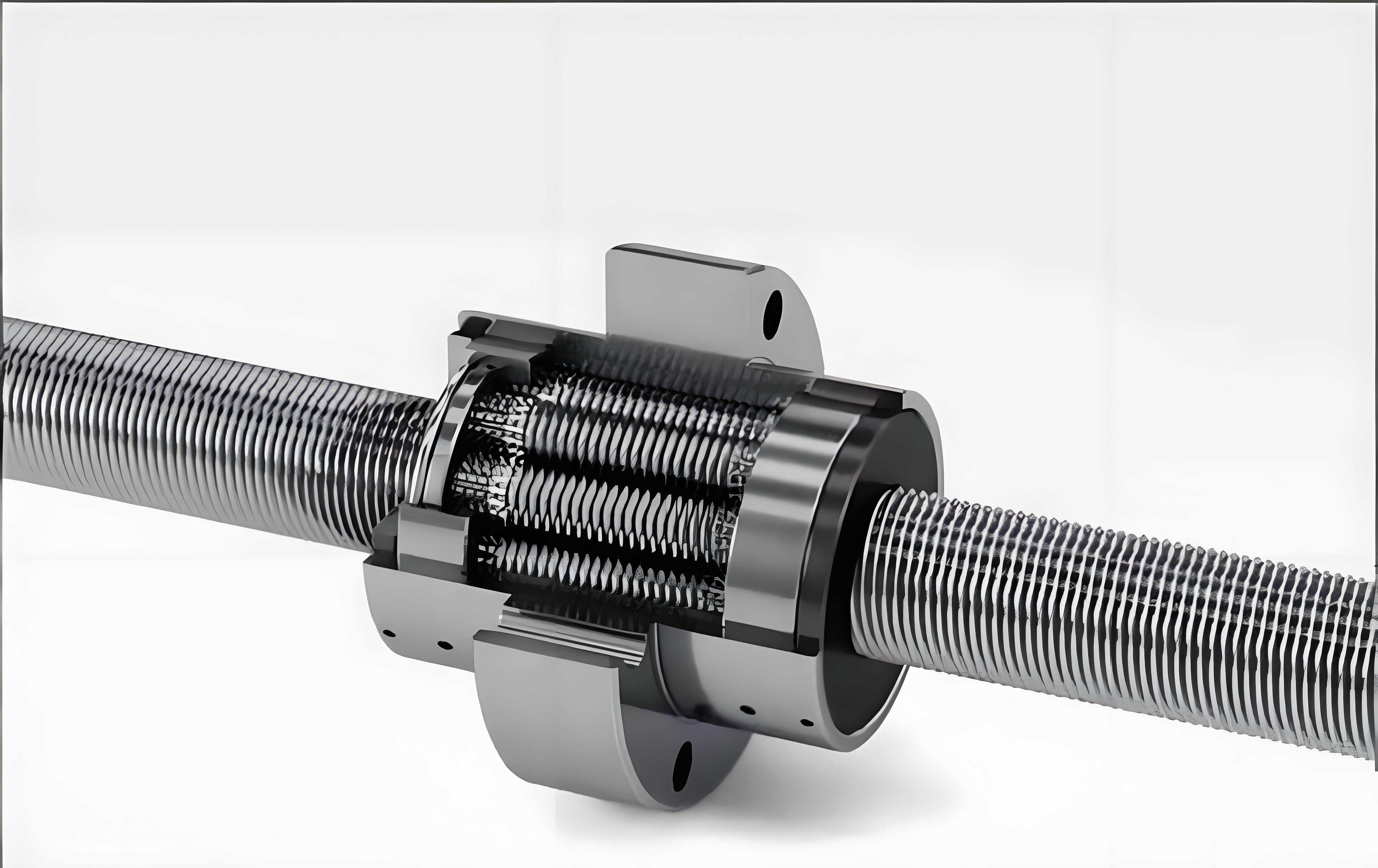

In the field of precision mechanical transmission, the planetary roller screw assembly has garnered significant attention due to its superior load-bearing capacity and longevity compared to traditional ball screw systems. As a critical component in aerospace and high-precision industrial applications, it efficiently converts rotational motion into linear motion. However, the performance of a planetary roller screw assembly is highly sensitive to manufacturing and assembly imperfections. Among these, assembly errors—often arising from misalignments during installation—can drastically alter the load distribution among the rollers, leading to uneven wear, reduced efficiency, and potential failure. In this article, I will delve into a comprehensive analysis of how assembly errors affect the load distribution across the threaded teeth of the rollers in a planetary roller screw assembly. By developing a mathematical model based on Hertzian contact theory, deformation compatibility, and static equilibrium, and validating it through finite element analysis, I aim to provide insights that can guide the design and assembly processes to enhance load-sharing characteristics and overall reliability.

The planetary roller screw assembly consists of three primary components: the screw, the rollers, and the nut. During operation, the screw rotates, driving the rollers, which in turn move the nut linearly. The rollers are typically arranged circumferentially around the screw, and they engage with both the screw and the nut via threaded interfaces. This design allows for high load capacity and stiffness. However, the assembly process often introduces errors. In typical installations, the screw is connected to a motor and supported by a bearing housing, while the nut is fixed to a sliding rail. Dimensional tolerances in the vertical direction of the bearing housing and rail can cause the central axes of the screw and nut to be offset. This offset, denoted as t, where t = hs – hn (with hs being the distance from the screw axis to the support plane and hn the distance from the nut axis to the support plane), disrupts the ideal uniform distribution of rollers. When t > 0, the screw is offset upward relative to the nut; when t < 0, it is offset downward. This misalignment changes the center distances between the screw and each roller, leading to pre-loads or gaps even before external loads are applied. Understanding these effects is crucial for optimizing the planetary roller screw assembly.

To analyze the load distribution, I first consider the geometry of the planetary roller screw assembly under assembly error. Let the standard center distance between the screw and a roller be rsr. For a planetary roller screw assembly with k rollers, the center of the screw is at point OS, the center of the nut at ON, and the center of the j-th roller at Ojr. The actual center distance rjsr for the j-th roller can be derived using the law of cosines:

$$ r^{j}_{sr} = \sqrt{r_{sr}^2 + t^2 – 2 r_{sr} t \cos \theta_j} $$

where θj is the angle between the line connecting Ojr and ON and the positive x-axis. If rjsr < rsr, the roller and screw experience interference, resulting in contact deformation and assembly stress. Conversely, if rjsr > rsr, a gap forms, and the roller may become unloaded. The range of rollers in contact can be determined geometrically. On a circle centered at ON with radius rsr, points where the roller center distance equals rsr define the boundaries of contact. Rollers within the smaller arc segment remain in contact with pre-load, while those on the larger arc may lose contact. This geometric analysis is foundational for modeling load distribution in a planetary roller screw assembly with assembly errors.

Next, I develop a load distribution model that incorporates assembly stresses. The model is based on several assumptions: all deformations are within the elastic range, bending of the screw shaft is negligible, and the engagement points on both sides of each roller are symmetric about the screw axis. For the j-th roller, the assembly error induces a normal contact deformation δjs on the screw side. This deformation can be resolved into two components: δjs1 along the line connecting OS and Ojr, and δjs2 in the axial direction. The angle between these components is the thread lead angle β, so:

$$ \delta^{j}_{s2} = \delta^{j}_{s1} \tan \beta $$

The radial deformation due to assembly error is:

$$ \delta^{j}_{s1} = r_{sr} – r^{j}_{sr} $$

Using Hertzian contact theory, the axial load on the screw-side threads of the j-th roller due to assembly stress, Fjsa, is related to the axial deformation by:

$$ (F^{j}_{sa})^{2/3} = \frac{\delta^{j}_{s2}}{C} $$

where C is the contact stiffness between the roller and screw, which depends on material properties and geometry. For a planetary roller screw assembly, the contact stiffness can be derived from the Hertz formula for cylindrical contacts. Assuming the screw and roller are equivalent cylinders with radii equal to their pitch diameters, C is given by:

$$ C = \frac{2}{3} \left( \frac{1 – \nu_s^2}{E_s} + \frac{1 – \nu_r^2}{E_r} \right)^{-1} \sqrt{\frac{R_s R_r}{R_s + R_r}} $$

where E and ν are the elastic modulus and Poisson’s ratio, and R denotes the equivalent radius. For the planetary roller screw assembly, the screw and roller materials are often identical, simplifying the expression. Based on static equilibrium, the axial deformation on the nut side, δjN2, equals δjs2. Thus, assembly stress causes axial displacement of engagement points on both sides of the roller. For the j-th roller, the axial distance between corresponding engagement points on the screw and nut sides changes from the nominal pitch P to Sj, where Sj = P + 2δjs2. This shift alters the deformation compatibility conditions when an external load is applied.

When an external axial load F is applied via the motor, the total axial load on the screw threads is the sum of F and the assembly stresses from all rollers in contact. Let m be the number of rollers in contact (where m ≤ k), and let each roller have n engaged threads. Then, the total assembly-induced axial force on the screw is Σj=1m n Fjsa. The equilibrium equation for the screw in the axial direction is:

$$ F + \sum_{j=1}^{m} n F^{j}_{sa} = m F^{j}_{s} $$

where Fjs is the total axial force on the screw side for the j-th roller. For each roller, the axial forces on the screw and nut sides are equal due to equilibrium:

$$ F^{j}_{s} = F^{j}_{r} $$

where Fjr is the total axial force on the nut side. To determine the load distribution per thread, consider the deformation compatibility between adjacent engagement points. For any two consecutive engagement points on the screw, say Pjs(i-1) and Pjs(i), the axial deformation of the screw segment between them, ΔLi, is:

$$ \Delta L_i = \sum_{q=1}^{z+1} \frac{F_q \Delta P_q}{E A_s} $$

Here, z is the number of other roller engagement points between Pjs(i-1) and Pjs(i), Fq is the axial internal force in each sub-segment, ΔPq is the length of the sub-segment, E is the elastic modulus, and As is the cross-sectional area of the screw. The deformation compatibility equation for two engagement points on the same roller is:

$$ L + \delta_{i+1} + \Delta L_{si} = L + \Delta L_{ri} + \delta_i $$

where L is the nominal distance (equal to pitch P), δi and δi+1 are contact deformations at the points, ΔLsi is the axial deformation of the screw between points, and ΔLri is the axial deformation of the roller. For multiple rollers, the physical relationship between axial deformations can be expressed using similar triangles, as shown in the geometry of the planetary roller screw assembly:

$$ \frac{L_2 – \Delta L_2}{L_1 – \Delta L_1} = \frac{L_2}{L_1} $$

By combining these equations—Hertzian contact, deformation compatibility, physical relations, and equilibrium—I establish a system of equations that can be solved for the axial load on each thread of every roller. This model accounts for assembly errors by incorporating the initial deformations δjs2 and the changed axial distances Sj. The solution provides the load distribution across the threaded teeth on both sides of each roller in the planetary roller screw assembly.

To illustrate the model, I consider a specific example of a planetary roller screw assembly with parameters listed in the table below. The assembly has 4 rollers (k = 4), but only some may be in contact due to error. The material is GCr15 steel with elastic modulus E = 2.12 × 1012 Pa and Poisson’s ratio ν = 0.29. The assembly error is set to t = 0.5 mm. The geometric parameters are as follows:

| Geometric Parameter | Screw | Roller | Nut |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pitch Diameter (mm) | 19.5 | 6.5 | 32.5 |

| Pitch (mm) | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| Number of Thread Starts | 4 | 1 | 4 |

| Number of Threads per Roller | — | 20 | — |

| Lead (mm) | 2.0 | 0.4 | 2.0 |

| Thread Half-Angle (degrees) | 45 | 45 | 45 |

The positions of the rollers relative to the nut center are defined by the angle θj: Roller 1 at 0°, Roller 2 at 90°, Roller 3 at 180°, and Roller 4 at 270°. Using the model, I calculate the center distance rjsr for each roller. For t = 0.5 mm and rsr = (19.5 + 6.5)/2 = 13 mm (assuming pitch diameters as reference), the actual distances are computed. Then, the assembly-induced axial deformations δjs2 and loads Fjsa are determined. Assuming an external axial load F = 20 kN (corresponding to the rated capacity of 2 tons), the system of equations is solved numerically using MATLAB. The results show the axial load per thread on both the screw and nut sides for each roller. Below is a summary table of the total axial load per roller:

| Roller Number (j) | Angle θj (degrees) | Center Distance rjsr (mm) | Assembly Axial Load Fjsa (N) | Total Axial Load (Screw Side) Fjs (N) | Total Axial Load (Nut Side) Fjr (N) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | 12.75 | 150.3 | 5250.8 | 5250.8 |

| 2 | 90 | 13.02 | 0 (No contact) | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 180 | 12.75 | 150.3 | 5250.8 | 5250.8 |

| 4 | 270 | 12.48 | 320.7 | 9498.4 | 9498.4 |

The load distribution per thread along the engagement length can be plotted. For instance, for Roller 4 (with the smallest center distance), the axial load is highest, while Roller 2 (with a center distance larger than standard) carries no load—this is the “no-load” phenomenon. Rollers 1 and 3, being symmetric about the y-axis, share equal loads. The non-uniform distribution highlights the impact of assembly error on the planetary roller screw assembly. To visualize, the axial load per thread for the screw side across all rollers might show a linear decrease from the first to the last thread due to the deformation gradient, but with magnitudes varying per roller. The mathematical model outputs these detailed distributions, which are crucial for stress analysis and fatigue life prediction in a planetary roller screw assembly.

To validate the model, I conduct a finite element analysis (FEA) using Abaqus. The planetary roller screw assembly is meshed with C3D8M elements, with finer mesh on the rollers (contact master surface) compared to the screw and nut (contact slave surfaces). The model contains approximately 4 million elements and 9.7 million nodes, ensuring accuracy. Boundary conditions are applied: the screw end is fixed, while the rollers and nut are constrained to allow only axial translation. A reference point coupled to the nut face is used to apply the axial load. The analysis is performed in three steps. First, initial contact is established between the screw, rollers, and nut. Second, a displacement of 0.5 mm is applied to the screw to simulate the assembly error, generating assembly stresses. Third, an axial force of 20 kN is applied at the nut reference point. The FEA results extract the axial forces on each roller. Comparing these with the mathematical model shows good agreement, as summarized below:

| Roller Number | Model-Predicted Axial Load (N) | FEA Axial Load (N) | Relative Error (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5250.8 | 5180.2 | 1.35 |

| 2 | 0 | ≈0 | — |

| 3 | 5250.8 | 5195.6 | 1.05 |

| 4 | 9498.4 | 9410.3 | 0.93 |

The close match validates the correctness of the analytical model for the planetary roller screw assembly under assembly errors. The slight discrepancies may arise from simplifications in the model, such as neglecting local stress concentrations or assuming perfect cylindrical contacts. Nonetheless, the model reliably captures the load distribution trends.

The implications of assembly errors on a planetary roller screw assembly are profound. My analysis shows that even small misalignments (e.g., t = 0.5 mm) can cause significant load imbalance. Rollers with increased center distances may become inactive, reducing the effective number of load-bearing rollers and increasing the load on others. This uneven distribution accelerates wear and may lead to premature failure. For instance, in the example, Roller 4 carries nearly double the load of Rollers 1 and 3, while Roller 2 is unloaded. Over time, this could cause pitting or fatigue on the highly loaded roller threads. Moreover, the assembly stress itself adds to the contact pressures, potentially exceeding yield limits if not accounted for. Therefore, in designing a planetary roller screw assembly, it is essential to control assembly tolerances. The vertical dimensions of bearing housings and rails should be tightly specified to minimize offset t. Additionally, pre-load adjustments or selective assembly techniques might be employed to compensate for errors. The model presented here can serve as a tool for sensitivity analysis, helping engineers determine acceptable tolerance limits for a given planetary roller screw assembly.

Beyond static analysis, the dynamic behavior of a planetary roller screw assembly under assembly errors warrants attention. Variations in load distribution can affect vibration characteristics and noise generation. For example, an unloaded roller might introduce backlash or impact forces during reversal. Future work could extend the model to include dynamic effects, such as inertia and damping, or thermal expansion, which might interact with assembly errors. Also, the model assumes linear elasticity; for high-load applications, plastic deformation or creep could be considered. Another aspect is the efficiency of the planetary roller screw assembly. Uneven loads may increase friction losses due to higher contact pressures on some rollers. By optimizing assembly alignment, efficiency can be improved. In practice, installation procedures for a planetary roller screw assembly should include alignment checks using dial indicators or laser systems to ensure coaxiality between screw and nut axes. The mathematical model can be integrated into design software to predict load distributions for various error scenarios, aiding in robust design.

In conclusion, I have developed a comprehensive analytical model to study the load distribution in a planetary roller screw assembly considering assembly errors. The model integrates Hertzian contact theory, deformation compatibility, physical equations, and static equilibrium to compute the axial loads on each thread of every roller. Through a detailed example and finite element validation, I demonstrate that assembly errors lead to non-uniform load sharing, with some rollers experiencing overload while others may become inactive. The key findings are: (1) Rollers with center distances larger than the standard may carry zero load, creating a “no-load” condition. (2) Rollers symmetric about the misalignment axis share equal loads. (3) The roller with the smallest center distance bears the highest axial load. These insights emphasize the importance of precision assembly in planetary roller screw applications. By minimizing alignment offsets, manufacturers can enhance load distribution, extend service life, and improve reliability. The model provides a foundation for further research into dynamic and thermal effects, as well as a practical tool for design optimization of planetary roller screw assemblies in high-performance systems.

To further illustrate the mathematical framework, here are the core equations used in the model for a planetary roller screw assembly:

1. Center Distance with Assembly Error:

$$ r^{j}_{sr} = \sqrt{r_{sr}^2 + t^2 – 2 r_{sr} t \cos \theta_j} $$

2. Assembly-Induced Axial Deformation:

$$ \delta^{j}_{s2} = (r_{sr} – r^{j}_{sr}) \tan \beta $$

3. Hertzian Contact Load-Deformation Relation:

$$ (F^{j}_{sa})^{2/3} = \frac{\delta^{j}_{s2}}{C} $$

4. Screw Axial Equilibrium:

$$ F + \sum_{j=1}^{m} n F^{j}_{sa} = \sum_{j=1}^{m} F^{j}_{s} $$

5. Deformation Compatibility for Engagement Points:

$$ P + \delta_{i+1} + \Delta L_{si} = P + \Delta L_{ri} + \delta_i $$

6. Axial Deformation of Screw Segment:

$$ \Delta L_i = \sum_{q=1}^{z+1} \frac{F_q \Delta P_q}{E A_s} $$

These equations, when solved simultaneously, yield the load distribution. For practical applications, numerical methods are employed due to the nonlinearity from Hertzian contact. The model’s accuracy has been confirmed via FEA, making it a valuable resource for engineers working with planetary roller screw assemblies. Future enhancements could include probabilistic analysis to account for random assembly errors or integration with system-level simulations for entire actuation systems. Ultimately, understanding and mitigating assembly errors will lead to more reliable and efficient planetary roller screw assemblies in demanding fields like aerospace, robotics, and industrial automation.