The planetary roller screw assembly (PRSA) represents a sophisticated mechanical actuator capable of converting rotary motion into linear thrust with exceptional efficiency, precision, and load capacity. Its superior performance stems from the multi-point contact load sharing between the threaded components. However, this advantage is contingent upon a reasonably uniform distribution of the applied axial load among the many engaged thread teeth. Non-uniform load distribution leads to premature wear, reduced fatigue life, and diminished stiffness of the assembly. Therefore, a comprehensive understanding of the factors governing this distribution is paramount for optimal design and application. This article develops a detailed analytical model to study the load distribution in a planetary roller screw assembly, with a particular focus on the significant influence of different mechanical installation configurations, structural parameters, and thread form geometry.

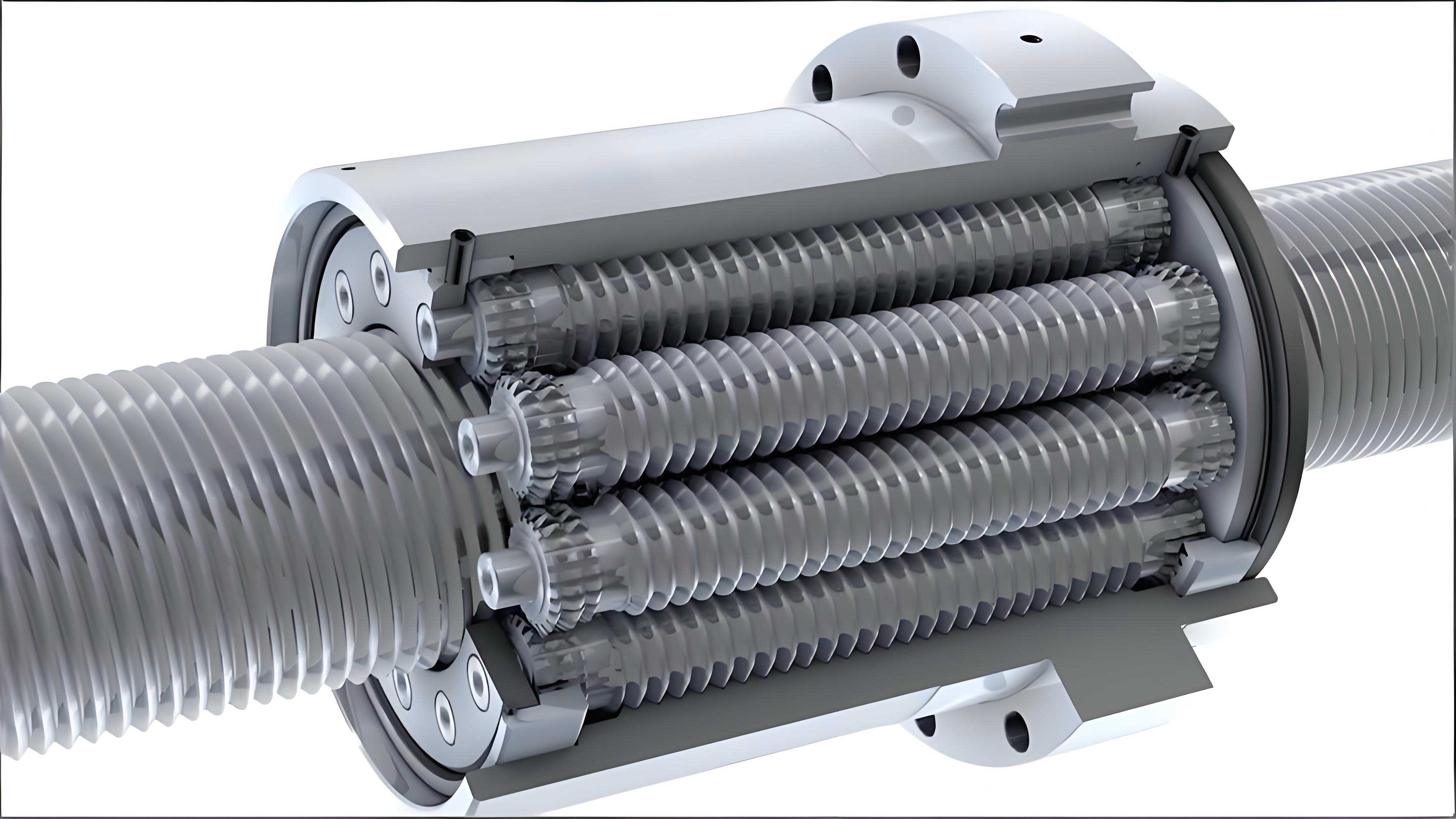

The core components of a standard planetary roller screw assembly include a central threaded screw, a set of planetary rollers (each with a single-start thread), and a surrounding nut with an internal thread. The rollers are distributed circumferentially around the screw and are meshed with both the screw and nut threads. To maintain proper phasing and prevent relative rotation, the ends of the rollers are geared and engage with internal ring gears fixed to the nut housing. A retainer or cage ensures even spacing of the rollers. The primary kinematic relationship is governed by the lead of the screw, which is the product of its pitch and the number of thread starts. A critical performance characteristic of any planetary roller screw assembly is its axial stiffness, which is directly related to the elastic deformations occurring under load.

To analyze the load distribution in a planetary roller screw assembly, a model must account for the primary sources of elastic deflection. We consider three fundamental types of compliance: 1) Shaft/Axial Segment Stiffness: The tensile/compressive deformation of the screw, roller, and nut bodies between adjacent loaded thread teeth. 2) Thread Tooth Bending Stiffness: The deflection of the individual thread teeth themselves under load, modeled as cantilever beams with complex root conditions. 3) Hertzian Contact Stiffness: The local elastic deformation at the point contacts between the mating thread flanks of the screw-roller and roller-nut interfaces. The interaction of these compliances under an external load determines how the total force is apportioned among the series of engaged thread pairs.

Mathematical Formulation of Stiffness Components

1. Axial Segment Stiffness

The axial stiffness of a segment of material between two thread teeth is derived from elementary mechanics. For the screw (S) and nut (N), the relevant length is one pitch, P. Considering Z rollers share the load, the effective stiffness for screw and nut segments is:

$$ k_{SB} = \frac{E_S A_S}{Z \cdot P}, \quad k_{NB} = \frac{E_N A_N}{Z \cdot P} $$

where \( E \) is the elastic modulus and \( A \) is the minimum cross-sectional area of the component. For the planetary roller, which is loaded from both ends by its meshes with the screw and nut, the effective loaded segment is half a pitch, leading to a roller body stiffness of:

$$ k_{RB} = \frac{E_R A_R}{P/2} = \frac{2 E_R A_R}{P} $$

2. Thread Tooth Bending Stiffness

The thread tooth is modeled as a short, tapered cantilever beam fixed at the root. Its total axial deflection \( \delta_{F} \) under an axial load \( F_a \) comprises several contributions: bending (\( \delta_1 \)), shear (\( \delta_2 \)), root tilt (\( \delta_3 \)), root shear (\( \delta_4 \)), and deformation due to the radial component of the load (\( \delta_5 \)). For a symmetric thread profile with a thread angle \( \theta \), the radial load component is \( F_r = F_a \tan(\theta/2) \). The individual deflections for a generic thread form are given by:

$$ \delta_1 = (1-\mu^2)\frac{3F_a}{4E} \cdot \frac{[1-(\frac{b}{a})^2 + 2\ln(\frac{a}{b})] \cdot [\cot^3(\theta/2) – 4(\frac{c}{a})^2 \cdot \tan(\theta/2)]}{???} $$

$$ \delta_2 = (1+\mu)\frac{6F_a}{5E} \cdot \cot^3(\theta/2) \cdot \ln(\frac{a}{b}) $$

$$ \delta_3 = (1-\mu^2)\frac{12c}{\pi E a^2} \cdot F_a \cdot \left( c – \frac{b}{2} \tan(\theta/2) \right) $$

$$ \delta_4 = (1-\mu^2)\frac{2F_a}{\pi E} \cdot \frac{P}{a} \left[ \ln\left( \frac{P+\frac{a}{2}}{P-\frac{a}{2}} \right)^2 + \frac{1}{2}\ln\left( \frac{4P^2}{a^2} – 1 \right) \right] $$

For an external thread (screw, roller), the radial compression term is:

$$ \delta_{5e} = (1-\mu) \cdot \frac{\tan^2(\theta/2)}{2} \cdot \frac{d_1}{P} \cdot \frac{F_r}{E} $$

For an internal thread (nut), the corresponding term is:

$$ \delta_{5i} = \left( \frac{D_0^2 + d^2}{D_0^2 – d^2} + \mu \right) \cdot \frac{\tan^2(\theta/2)}{2} \cdot \frac{d}{P} \cdot \frac{F_r}{E} $$

The total thread tooth stiffness is then \( k_{F} = F_a / \delta_{F} \). It is crucial to note that while the thread form angle \( \theta \) may be identical (commonly 90°), the stiffness values for the screw (\( k_{SF} \)), roller (\( k_{RF} \)), and nut (\( k_{NF} \)) threads differ due to their distinct effective dimensions (e.g., root diameter \( d_1 \), pitch diameter \( d \), nut housing diameter \( D_0 \)). Typically, \( k_{RF} > k_{SF} > k_{NF} \).

3. Hertzian Contact Stiffness

The contact between the convex spherical thread profile of the roller and the flat or slightly conforming thread flanks of the screw and nut is a point contact. According to Hertzian theory, the normal approach \( \delta \) under a normal load \( F_n \) is:

$$ \delta = \delta^* \left[ \frac{3F_n}{2\Sigma\rho} \left( \frac{1-\mu_R^2}{E_R} + \frac{1-\mu_X^2}{E_X} \right) \right]^{2/3} \cdot (\Sigma\rho)^{-1/3} $$

where \( \Sigma\rho \) is the sum of principal curvatures and \( \delta^* \) is a dimensionless parameter dependent on the curvature ratio. The normal load is related to the transmitted axial load \( F_a \) by the thread helix angle \( \alpha_R \) and the thread angle:

$$ F_n = \frac{F_a}{\cos\alpha_R \cdot \cos(\theta/2)} $$

The effective axial contact stiffness, relating axial force to axial deflection, is therefore:

$$ k_{XC} = \frac{F_a}{\delta \cdot \cos\alpha_R \cdot \cos(\theta/2)} = \frac{F_a^{1/3} \cdot K_{HX}^{2/3}}{\cos\alpha_R \cdot \cos(\theta/2)} $$

where \( K_{HX} \) consolidates the material and geometric constants from Hertz theory for interface X (S for screw-roller or N for roller-nut). This stiffness is non-linear, depending on \( F_a^{1/3} \).

Load Distribution Model for a Planetary Roller Screw Assembly

The model considers a single roller in mesh with both the screw and the nut, with n engaged thread pairs on each side. The total system of 2n thread pairs must satisfy equilibrium and compatibility conditions. The key compatibility condition exists within each closed loop formed by the screw, roller, and nut over one pitch, as shown in the conceptual deformation diagram. For the nut-side loop involving the i-th and (i+1)-th nut threads and the corresponding roller threads, the sum of axial deformations in the nut segment must equal the sum in the corresponding roller segments, as the nominal pitch is the same for all components.

Let \( F_{Ni} \) and \( F_{Si} \) denote the axial load on the i-th roller-nut and roller-screw thread pair, respectively. The deformation compatibility for the i-th nut-side loop can be expressed as:

$$ \sum_{j=1}^{i} \frac{F_{Nj}}{k_{NB}} + \frac{F_{Ni}-F_{Ni+1}}{k_{NT}} + \frac{F_{Ni}}{k_{NC}} = \sum_{j=1}^{i} \frac{F_{Sj} – \sum_{j=1}^{i-1} F_{Nj}}{k_{RB}} + \frac{F_{Ni+1}}{k_{RT}} – \frac{F_{Ni}}{k_{RT}} – \frac{F_{Ni}}{k_{RB}} – \frac{F_{Ni+1}}{k_{NC}} $$

A similar set of n-1 equations can be written for the screw-side loops. The global force equilibrium for the entire planetary roller screw assembly requires that the sum of all contact forces on either the screw or the nut equals the external axial load F:

$$ F = \sum_{i=1}^{n} F_{Si} = \sum_{i=1}^{n} F_{Ni} $$

This yields a total of 2n equations. However, the contact stiffness terms \( k_{SC} \) and \( k_{NC} \) are functions of \( F_{Si}^{1/3} \) and \( F_{Ni}^{1/3} \), rendering the system nonlinear. An iterative solution scheme is employed: 1) Assume uniform load distribution to calculate initial contact stiffnesses. 2) Solve the linearized system of equations. 3) Recalculate contact stiffnesses based on the new load distribution. 4) Iterate until convergence is achieved (\( |F_i^{k} – F_i^{k-1}| / F_i^{k-1} < \epsilon \)).

Influence of Installation Configuration

The mechanical installation of the planetary roller screw assembly profoundly affects load distribution. The two fundamental configurations are defined by the relative position of the reaction supports for the screw and nut.

Configuration A: Same-Side Support. Both the screw and nut are supported (e.g., by bearings) on the same axial side of the assembly. Under an external load, the screw and nut bodies experience cumulative axial deformations in the same direction relative to their supports.

Configuration B: Opposite-Side Support. The screw and nut are supported on opposite axial sides of the assembly. Here, the cumulative axial deformations of the screw and nut bodies occur in opposite directions.

Within each configuration, the direction of the external load (tension or compression on either component) defines the load case, but the distribution pattern relative to the supports remains qualitatively similar for a given configuration. The model is applied to analyze a sample planetary roller screw assembly with the parameters listed below.

| Parameter | Symbol | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Screw Pitch Diameter | \( d_s \) | 24 mm |

| Roller Pitch Diameter | \( d_R \) | 8 mm |

| Nut Pitch Diameter | \( d_N \) | 40 mm |

| Nut Housing OD | \( D_0 \) | 55 mm |

| Screw/Roller/Nut Thread Angle | \( \theta \) | 90° |

| Pitch | \( P \) | 2 mm |

| Number of Rollers | \( Z \) | 8 |

| Number of Engaged Roller Threads | \( n \) | 20 |

| Component | Elastic Modulus, \( E \) | Poisson’s Ratio, \( \mu \) |

|---|---|---|

| Screw, Roller, Nut | 212 GPa | 0.29 |

The analysis reveals distinct load distribution patterns. In the opposite-side support configuration, the load on the screw-side threads is highest near the screw support and decreases towards the free end, while the load on the nut-side threads shows the opposite trend: lowest near the nut support and increasing towards the free end. This is because the cumulative axial stretching of the screw and compression of the nut (or vice-versa) differentially pre-loads the thread pairs at each end. In the same-side support configuration, the cumulative deformations of the screw and nut are in the same direction. This causes both the screw-side and nut-side thread loads to be highest near the supports and decrease towards the free ends. The load inequality is often more severe in this configuration.

The physical reason is the interplay between axial body stiffness and load distribution. The component with the lower axial body stiffness (typically the screw, due to its smaller cross-section) exhibits a larger cumulative deformation over the engaged length, leading to a more pronounced load gradient on its side. The nut, with its larger cross-sectional area and higher \( k_{NB} \), generally has a more uniform load distribution. The configuration determines whether these gradients are additive (same-side, worsening inequality) or compensatory (opposite-side, improving uniformity). For the longevity of the planetary roller screw assembly, the opposite-side support is generally preferable as it promotes more uniform roller loading over its entire length during each revolution.

Parametric Analysis of Load Distribution

1. Effect of Number of Engaged Roller Threads (n)

The number of load-bearing threads on each roller is a critical design parameter. Analysis shows that as n increases, the load distribution becomes increasingly non-uniform. For a small number of threads (e.g., n=10), the load is nearly evenly shared. As n increases to 20, 30, and 50, the load on the most heavily loaded thread pair (closest to the support in a same-side configuration) increases dramatically as a percentage of the average load. With n=50, a significant portion of the total load is carried by only the first few threads, drastically reducing the effective load-sharing capacity and potential fatigue life of the planetary roller screw assembly. Conversely, a very small n increases the average load per thread, raising contact stresses. An optimal value balances these effects.

2. Effect of Thread Form Parameters: Pitch and Tooth Height

The thread form, defined primarily by pitch \( P \) and tooth height \( h \), influences stiffness at multiple levels. The axial body stiffnesses \( k_{SB} \) and \( k_{NB} \) are inversely proportional to pitch \( P \). A smaller pitch directly increases these stiffnesses, thereby reducing the cumulative axial deformation for a given load and significantly improving load distribution uniformity. The thread tooth stiffness \( k_F \) is also affected by pitch and tooth height, but its influence on the overall distribution is secondary compared to the axial body stiffness. The following table summarizes the trend when scaling thread geometry.

| Geometric Change | Effect on Axial Body Stiffness | Effect on Thread Tooth Stiffness | Overall Impact on Load Distribution Uniformity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Decrease Pitch (\( P \downarrow \)) | Increases significantly (\( \propto 1/P \)) | Moderate increase | Strong improvement |

| Decrease Tooth Height (\( h \downarrow \)) | No direct effect (area constant) | Decreases (shorter lever arm) | Minor improvement (softer teeth allow more redistribution) |

| Decrease Both \( P \) and \( h \) proportionally | Increases significantly | Varies | Very strong improvement |

Therefore, designing a planetary roller screw assembly with a fine pitch is one of the most effective ways to achieve a uniform load distribution, albeit at the potential cost of reduced linear speed for a given rotational input.

Model Verification and Discussion

The validity of the proposed modeling approach can be assessed by comparing its results with those from other established methods, such as finite element analysis or simplified spring-network models from literature. A key point of differentiation in the present model is the inclusion of the detailed thread tooth bending compliance, particularly the radial compression term (\( \delta_5 \)), which is often neglected. This term is especially significant for the nut thread due to its different boundary conditions. Omitting it can lead to an overestimation of nut thread stiffness and a consequent under-prediction of load uniformity on the nut side. The iterative handling of the non-linear Hertzian contact stiffness is also crucial for accuracy under high loads.

The primary driver of non-uniform load distribution in a planetary roller screw assembly is the cumulative elastic deformation of the screw and nut bodies (axial segment deformation). This deformation creates a relative displacement gradient along the engagement length, progressively unloading thread pairs farther from the support. The installation configuration dictates whether the gradients from the screw and nut are synergistic or opposing. Secondary factors include the thread tooth flexibilities and the non-linear contact stiffness. The results underscore that achieving uniform load distribution requires maximizing the axial rigidity of the screw and nut components, selecting an opposite-side support configuration where possible, and optimizing the number of engaged threads and the pitch.

Conclusion

This article presents a comprehensive analytical framework for investigating the load distribution in a planetary roller screw assembly. The model integrates the axial stiffness of the component bodies, the bending stiffness of the individual thread teeth, and the non-linear Hertzian contact stiffness at the meshing interfaces. A pivotal finding is the dominant influence of the mechanical installation configuration. An opposite-side support arrangement for the screw and nut generates compensating deformation gradients, leading to a markedly more uniform load distribution compared to a same-side support arrangement. This uniformity is essential for maximizing the load capacity, fatigue life, and operational reliability of the planetary roller screw assembly.

Further, parametric studies elucidate the impact of key design variables. The number of engaged threads on the roller presents a trade-off; increasing it raises the potential load capacity but severely exacerbates distribution inequality. The thread pitch is identified as a highly influential parameter, where a finer pitch dramatically improves load sharing by increasing the axial body stiffness of the screw and nut. Thread tooth height and stiffness have a measurable but secondary effect.

In summary, the design and application of a high-performance planetary roller screw assembly must carefully consider installation kinematics alongside structural dimensions. The model provides a valuable tool for designers to predict load distribution, optimize parameters, and select the most favorable support configuration to ensure that the inherent multi-contact advantage of the planetary roller screw assembly is fully realized in practice.