In my extensive experience within the automotive component manufacturing sector, controlling distortion during heat treatment remains one of the most persistent and costly challenges. The pursuit of dimensional stability, especially for asymmetric gears, directly confronts the pervasive issue of heat treatment defects. These defects, primarily manifested as warping, twisting, and size variation, not only compromise component functionality but also escalate production costs through scrapped parts and secondary corrective operations. The common international solution for critical components like synchronizer rings and high-precision gears involves a press-quenching step after carburizing. While effective, this method significantly increases cycle time and cost, making it less desirable in today’s competitive, high-volume manufacturing environment. Therefore, my focus has been on developing and refining direct quenching methodologies paired with innovative fixturing to suppress heat treatment defects and bring deformation within acceptable technical limits without resorting to press-quenching for every part.

A prime example that consumed significant engineering effort was a camshaft gear for a domestic engine assembly. This mass-produced component, made from 20CrMnTiH steel, presented a classic case study in asymmetric distortion. While its web was not exceptionally narrow, its 11mm thickness and the presence of a substantial, offset central hub created a geometry highly susceptible to heat treatment defects. The technical specifications were stringent: surface hardness of 57-62 HRC, core hardness of 25-45 HRC, and an effective case depth of 0.61-1.2 mm (including a 0.2 mm grinding allowance) defined at 515 HV1. Metallurgical requirements mandated carbides, martensite, and retained austenite all within grades 1 to 3.

The post-heat-treatment grinding sequence was critically dependent on the gear’s geometry. Seven signal pads on one face were ground using the opposite back face for location. These pads then located the gear for grinding the back face, and finally, the back face again located the gear for grinding the front face. The seven signal pads had a tight dimensional tolerance of ±0.1 mm. Any significant distortion of the central hub face, where these pads are located, would render the subsequent grinding sequence impossible or lead to grinding through the case, a catastrophic heat treatment defect resulting in part rejection.

To meet a peak monthly demand of 8,000 pieces with a short cycle time, we committed to a standard direct quenching process after carburizing. The chosen thermal cycle involved carburizing followed by a temperature drop and a soak period before quenching in oil, all conducted in an RTQF-13 IPSEN multi-chamber furnace line. Initially, gears were loaded vertically using traditional fixtures. The overall process flow was: forging → isothermal normalizing of blanks → pre-machining → carburizing and quenching → tempering → cleaning/shot blasting → grinding → final inspection.

Despite meeting metallurgical specs, the initial production batches were plagued by severe heat treatment defects. The dominant failure mode was the twisting and translation of the central hub face, making the signal pads un-grindable. Furthermore, the distortion pattern was inconsistent from batch to batch. We embarked on a comprehensive optimization program, scrutinizing incoming material quality, isothermal normalizing parameters, carburizing profiles, and pre-machining dimensions. While these efforts improved the consistency of the distortion trend, the fundamental issue of hub face translation remained unresolved, leading to a growing inventory of non-conforming semi-finished parts.

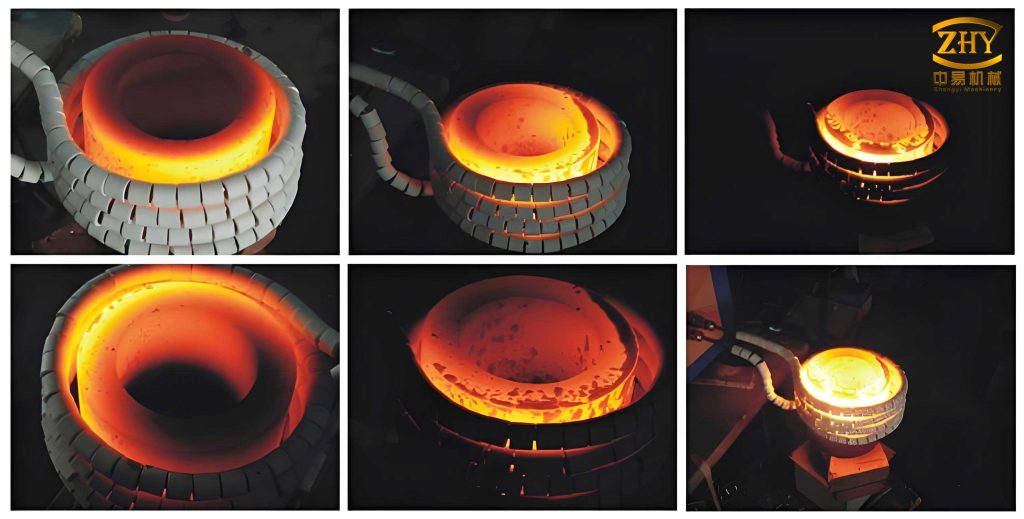

To salvage the existing stock, we utilized available resources: a rotary hearth furnace and a single-station press quench unit. A dedicated press-quench die was designed, comprising an upper die, a lower die with an oil containment shroud, and a central locating mandrel. The process involved reheating the carburized gears to the austenitizing temperature in the rotary furnace and then transferring them to the press quench, where the dies physically constrained the gear during the martensitic transformation to flatten the distorted hub.

A detailed cost analysis of this salvage operation highlighted why it couldn’t be the primary solution. The total cost per piece for press quenching was calculated from energy, atmosphere, and labor costs. The formulas below summarize the calculation:

Energy cost for the rotary furnace: $$ C_{rf} = P_{rf} \times t \times R_{elec} $$ where \( P_{rf} = 128 \text{ kW} \), \( R_{elec} = 0.72 \text{ USD/kWh} \), and \( t \) is the time in hours. For one hour, \( C_{rf} = 128 \times 0.72 = 92.16 \text{ USD} \).

Energy cost for the press quench: $$ C_{pq} = P_{pq} \times t \times R_{elec} $$ with \( P_{pq} = 48.1 \text{ kW} \), giving \( C_{pq} = 48.1 \times 0.72 = 34.632 \text{ USD} \).

Methanol cost: $$ C_{meoh} = F_{meoh} \times \rho_{meoh} \times t \times R_{meoh} $$ with flow rate \( F_{meoh} = 2 \text{ L/h} \), density \( \rho_{meoh} = 0.8 \text{ kg/L} \), and price \( R_{meoh} = 4 \text{ USD/kg} \). Thus, \( C_{meoh} = 2 \times 0.8 \times 4 = 6.4 \text{ USD/h} \).

Propane cost: $$ C_{prop} = F_{prop} \times \rho_{prop} \times t \times R_{prop} $$ with flow rate \( F_{prop} = 0.7 \text{ m}^3/\text{h} \), density \( \rho_{prop} = 1.76 \text{ kg/m}^3 \), and price \( R_{prop} = 7.168 \text{ USD/kg} \). Thus, \( C_{prop} = 0.7 \times 1.76 \times 7.168 = 8.83 \text{ USD/h} \).

The press quench cycle yielded 11 pieces per hour. The labor cost was 1 USD per piece. Therefore, the total cost per piece \( C_{total} \) was:

$$ C_{total} = \frac{C_{rf} + C_{pq} + C_{meoh} + C_{prop}}{N} + C_{labor} $$

$$ C_{total} = \frac{92.16 + 34.632 + 6.4 + 8.83}{11} + 1 = 12.911 + 1 = 13.911 \text{ USD} $$

Given the semi-finished value of a gear at 54.39 USD, the salvage cost represented \( (13.911 / 54.39) \times 100\% \approx 25.6\% \) of its value. This was economically viable for salvage but prohibitive for 100% application, not to mention the bottleneck created by the low throughput of 11 pieces per hour. This reinforced the need to eliminate the root cause of the heat treatment defects in the primary carburize-and-quench process.

We conducted a controlled furnace load experiment to quantitatively understand the deformation vector. Thirty-two gears were loaded vertically in two layers, and key dimensions were measured before and after heat treatment: the flatness of the gear face and the height difference \( a \) (or \( b \)) of the hub face relative to the primary gear face. A positive value indicates the hub protrudes beyond the primary face. The results are summarized in the table below.

| Gear ID | Pre-HT Flatness (mm) | Pre-HT Hub Height, a (mm) | Post-HT Flatness (mm) | Post-HT Hub Height, b (mm) | Hub Translation, Δ = a – b (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.08 |

| 2 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.07 | -0.15 | 0.23 |

| 3 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.12 | -0.10 | 0.20 |

| 4 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.07 | -0.01 |

| 5 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.18 | -0.07 | 0.17 |

| 6 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.16 | 0.08 | -0.01 |

| 7 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.07 | -0.03 | 0.11 |

| 8 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.02 |

| 9 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.15 | 0.06 | 0.01 |

| 10 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.06 |

| 11 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.12 | -0.18 | 0.22 |

| 12 | 0.03 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.05 |

| 13 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.13 | 0.05 | 0.03 |

| 14 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.06 |

| 15 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| 16 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.05 | -0.03 |

| 17 | 0.04 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.07 | 0.03 |

| 18 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.07 | -0.05 | 0.11 |

| 19 | 0.04 | 0.10 | 0.06 | -0.07 | 0.17 |

| 20 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.10 | -0.07 | 0.14 |

| 21 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.10 | -0.10 | 0.16 |

| 22 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.05 | -0.15 | 0.21 |

| 23 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.01 |

| 24 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.03 |

| 25 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.08 | -0.04 | 0.11 |

| 26 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.07 | -0.04 | 0.11 |

| 27 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.04 | -0.03 | 0.09 |

| 28 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.02 |

| 29 | 0.04 | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.03 |

| 30 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.02 | 0.08 |

| 31 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.09 | -0.04 | 0.11 |

| 32 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.20 | -0.05 | 0.15 |

The data revealed a clear and dominant trend: the central hub consistently translated towards the gear’s back face during heat treatment. The translation magnitude \( \Delta \) exceeded 0.10 mm for nearly half the batch, directly causing the grinding heat treatment defects. The root causes were identified as twofold. First, gravitational creep during the high-temperature austenitizing soak, exacerbated by the asymmetric mass distribution. Second, and more critically during quenching, the differential cooling rates and the non-simultaneous martensitic transformation between the thin web and the thick hub generated severe transformational stresses. The free deformation state during direct quenching was the primary enabler of these heat treatment defects.

The breakthrough came from re-imagining the fixturing strategy not as a simple carrier, but as a constraining tool to counteract these forces. We designed a simple three-claw fixture. This fixture presented three discrete contact points to support the gear’s hub face, arranged circumferentially. The radial length of the claws was designed to accommodate the gear diameter without interfering with the cooling of the gear’s outer periphery. Crucially, we changed the loading orientation: the gear was placed with its hub face *down* on the three-claw fixture, which was then stacked on a standard honeycomb-style furnace tray. This configuration used the fixture to physically resist the gravitational and transformational forces pushing the hub face inward. The small contact area and machined oil drainage grooves on the claws ensured uniform cooling and hardness.

Initial trials with five prototype fixtures across ten furnace loads, processing 50 gears, were unanimously successful. The hub face translation was eliminated; flatness was consistently held within 0.10 mm, well within the grinding allowance. All trial parts were successfully ground without any heat treatment defects. This proved the concept that a well-designed support fixture could mitigate the specific distortion modes of an asymmetric gear in a direct quench process. While our initial fixtures were made from standard 3Cr25Ni20Si2 alloy with limited durability, they provided the theoretical foundation for a production-ready solution.

We subsequently collaborated with a specialized heat treatment fixture manufacturer to develop a dedicated, high-volume fixture system. The design was optimized for symmetrical load-bearing and minimal thermal stress concentration. The material was upgraded to HR17Nb for superior high-temperature strength and creep resistance, targeting a service life of two years. This robust, full-furnace-load fixture system now allows for the cost-effective, high-throughput production of this camshaft gear using the direct quench method, effectively eradicating the previously endemic heat treatment defects related to hub distortion.

This case underscores a broader principle: there is no universal fixture for all gears. Controlling heat treatment defects requires a tailored approach based on component geometry. Through practice, we have developed a library of personalized fixture concepts for different part families. For symmetric gears, a standard vertical comb-style fixture maximizes load density while controlling runout. For wide-face intermediate shaft gears, a simple bar-fixture, where gears are stacked on a fixed rod, provides alignment and prevents tilting. For parts prone to internal distortion, like thin-walled gears with large bores or asymmetric coupling sleeves, a flat-plate or “stacking tray” fixture with locating pins is essential. This fixture supports the entire face, preventing ovality of bores or taper of internal splines—common heat treatment defects in such components—by ensuring even support and minimizing point-loading during the quench.

The control of distortion, a predominant class of heat treatment defects, is profoundly influenced by the fixturing strategy. The case of the asymmetric camshaft gear demonstrates that for structural asymmetry, a supportive, constraining fixture like the three-claw design can be highly effective in controlling specific translation or warpage modes. The economic benefits of implementing such optimized, high-durability fixtures for high-volume parts are substantial. Ultimately, the selection of loading method and fixture design must be an integral part of the heat treatment process design, tailored to the component’s unique geometry to proactively suppress the root causes of heat treatment defects and achieve consistent dimensional quality in a cost-effective manufacturing flow.