In my extensive career as a heat treatment specialist, I have confronted countless instances of heat treatment defects that threaten the integrity and performance of critical automotive components. The challenge is particularly acute for parts like rear axle spiral bevel gear shafts, where precision and durability are non-negotiable. This article delves deep into the nature of these heat treatment defects, presents a proven methodology for their correction, and extends the discussion to the longevity of essential equipment like high-temperature mesh belts. My aim is to share a comprehensive, first-hand account that blends theoretical understanding with hard-won practical insights.

The core of the problem lies in the inherent conflict during thermal processing. To achieve desired material properties—high surface hardness, wear resistance, and a tough core—components undergo severe thermal cycles. For the driving pinion shaft of an automobile rear axle, this typically involves carburizing and quenching from temperatures around 850°C. The rapid cooling induces significant martensitic transformation, generating intense internal stresses. These stresses, if not managed, manifest as the most common and troublesome of all heat treatment defects: distortion and warpage. The geometry of the pinion shaft, with its substantial diameter and stepped design, makes it exceptionally susceptible. Distortion values typically range from 0.1 mm to 0.3 mm, with extreme cases reaching 0.5 mm. Such deviation is catastrophic for gear meshing, leading to noise, elevated oil temperatures, improper contact patterns, and ultimately, premature failure through pitting, wear, or tooth fracture.

Attempting cold straightening on these hardened shafts (surface hardness 58-62 HRC) is futile at low pressures and disastrous at high pressures. Pressures exceeding a certain threshold simply cause brittle fracture at the stress-concentrating stepped sections. This forced the realization that thermal assistance was indispensable. The quest was to find a method that applied enough thermal energy to facilitate plastic flow for correction without degrading the carefully engineered surface properties—a delicate balance to avoid introducing new heat treatment defects like soft spots or re-hardening cracks.

After systematic experimentation, we developed a localized high-frequency induction heating and hot-pressing technique. The principle can be modeled by considering the yield strength reduction with temperature. The relationship between flow stress ($\sigma_f$), temperature (T), and strain rate ($\dot{\epsilon}$) is often approximated by a constitutive equation such as:

$$\sigma_f = K \cdot (\dot{\epsilon})^m \cdot \exp\left(\frac{Q}{RT}\right)$$

Where $K$ is a material constant, $m$ is the strain rate sensitivity, $Q$ is the activation energy for deformation, and $R$ is the universal gas constant. By locally elevating the temperature at the convex side of the bend (specifically around the bearing seat step), we drastically lower $\sigma_f$, allowing permanent correction under manageable press loads.

| Process Parameter | Optimal Range / Value | Physical Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Heating Temperature | 700°C – 800°C | Sufficient to lower yield strength below applied stress, yet below Ac1 to avoid austenitization and decarburization. |

| Heating Method | Localized High-Frequency Induction | Rapid, controlled heat input minimizing total heat-affected zone (HAZ) and thermal exposure time. |

| Applied Press Force | Empirically determined to achieve over-bending | Must exceed the elastic limit of the heated zone to induce plastic deformation. |

| Over-bending Amount ($\delta_{over}$) | 0.07 mm – 0.12 mm | Accounts for elastic springback upon unloading and cooling. |

| Measured Springback ($\delta_{springback}$) | 0.06 mm – 0.07 mm | Elastic recovery dictated by the modulus of elasticity at temperature: $\delta_{springback} \propto \frac{\sigma \cdot L}{E(T)}$. |

| Post-Straightening Hardness at Heated Zone | > 52 HRC | Fast heating/cooling cycle minimizes tempering effects; area is for bearing fit, not active gear mesh. |

| Final Straightness Tolerance | Within drawing specification | Achieved for >95% of components. |

The success of this correction hinges on precise control. The over-bending is critical. The final corrected dimension ($\delta_{final}$) can be expressed as:

$$\delta_{final} = \delta_{initial} + \delta_{plastic} – \delta_{springback}$$

Where $\delta_{initial}$ is the initial distortion, $\delta_{plastic}$ is the permanent deformation induced by hot-pressing, and $\delta_{springback}$ is the elastic recovery. We target $\delta_{final} = 0$. Therefore, the required plastic deformation is $\delta_{plastic} = -\delta_{initial} + \delta_{springback}$. Since $\delta_{springback}$ is positive, we must press “beyond” straight by that amount. Subsequent shot peening is mandatory to impart beneficial compressive residual stresses, enhancing fatigue resistance and stabilizing the correction by mitigating the tensile stresses that are classic contributors to heat treatment defects like stress-corrosion cracking. The economic impact is substantial, transforming a 10% scrap/rework rate into near-zero, yielding significant annual savings.

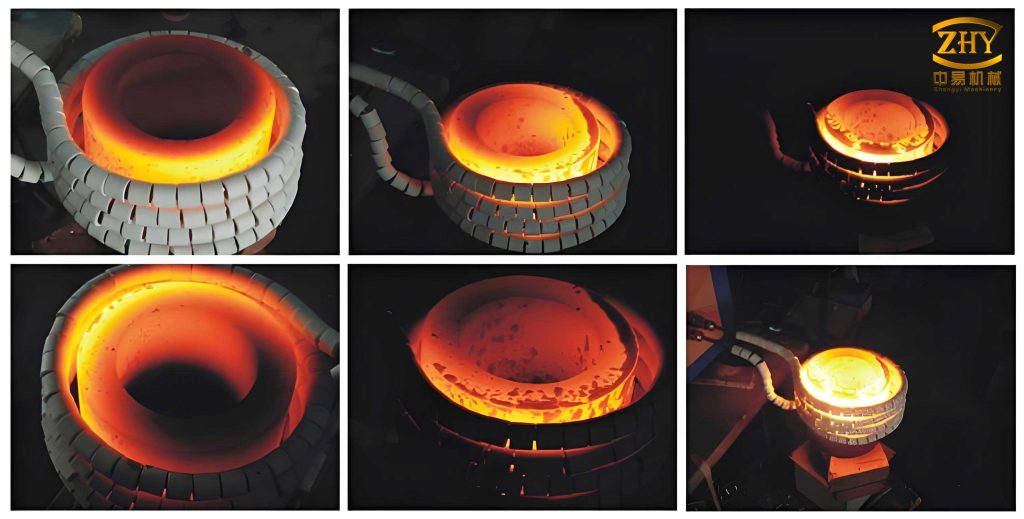

However, the battle against heat treatment defects is not confined to the workpiece alone. The equipment that facilitates the heat treatment, such as continuous mesh belt furnaces, is itself a source of failure and cost if not properly engineered. The mesh belt, operating in temperatures ranging from 800°C to 950°C, is subjected to creep, oxidation, and thermal fatigue. Its premature failure is a severe production disruption and a major cost contributor. From firsthand analysis and collaboration with manufacturers, I’ve identified that the root causes of short belt life are themselves a category of design and material selection heat treatment defects.

The traditional choice of Cr20Ni80 alloy, while serviceable, often falls short in longevity under aggressive cycling. The primary failure modes include sagging, distortion of side plates (“flagging”), and embrittlement leading to link rod fracture. We pioneered a shift to a superior alloy, 1Cr25Ni20SiZ (similar to AISI 310 with silicon). The improvement is not merely compositional but stems from enhanced high-temperature strength and oxidation resistance. The benefit of silicon additions in forming a protective SiO2 layer cannot be overstated. The creep rupture strength ($\sigma_{rupture}$) at a given temperature and time is fundamentally higher for the 25/20 Si grade. This can be compared using Larson-Miller parameters:

$$P_{LM} = T \cdot (C + \log t)$$

Where $T$ is temperature in Kelvin, $t$ is time in hours, and $C$ is a constant (~20 for many alloys). For a target life $t$, the allowable stress for 1Cr25Ni20SiZ is higher at the same $P_{LM}$ value.

| Aspect | Conventional Approach (Cr20Ni80) | Optimized Approach (1Cr25Ni20SiZ + Design) | Impact on Life and Heat Treatment Defects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Material Composition | ~20% Cr, ~80% Ni | ~25% Cr, ~20% Ni, ~1.5% Si | Superior oxidation & creep resistance; forms stable Cr2O3/SiO2 scale. Reduces thinning and embrittlement defects. |

| Typical Cost (Relative) | 1.0x (Baseline) | ~0.8x – 1.0x (Material costlier, but design efficiency lowers total cost) | Lower total cost of ownership despite higher raw material cost. |

| Design Structure | Standard woven or rod-type with simple baffles | “Herringbone” baffle design with optimized pitch (P) and spacing (S) | Distributes load evenly; prevents part jamming and belt distortion; reduces stress concentration defects. |

| Key Design Parameters | P, S often not optimized for specific load | P and S calculated based on part weight, furnace temperature gradient, and desired belt flexibility. $S_{opt} \propto \sqrt{W/\rho}$ where W is part load. | Minimizes permanent set and cross-rod deformation. |

| Typical Service Life | 3,000 – 5,000 hours | >7,500 hours (documented cases exceeding 7,000h) | Reduces frequency of catastrophic belt failure defects. |

| Primary Failure Mode | Baffle collapse, structural unraveling, rod fracture | Gradual, even wear; localized rod replacement possible without full belt failure | Transforms failure from sudden to manageable, predictable wear. |

The structural innovation is as vital as the material. The herringbone baffle design provides superior lateral stability. The mechanical advantage can be conceptualized by considering the bending moment on a baffle. For a standard vertical baffle under a side load $F$, the bending stress $\sigma_b$ at the root is:

$$\sigma_b = \frac{M \cdot c}{I} = \frac{F \cdot h \cdot (t/2)}{(w \cdot t^3)/12} = \frac{6Fh}{w t^2}$$

Where $h$ is height, $t$ is thickness, $w$ is width, and $c$ is the distance from neutral axis. The herringbone design, by angling the baffle, reduces the effective moment arm $h$ and introduces a supporting component from adjacent structure, thereby lowering $\sigma_b$ and the propensity for this mechanical heat treatment defect (baffle failure).

Furthermore, the entire heat treatment process is a system. The control of atmosphere, temperature uniformity, and quenching medium are all potential sources of heat treatment defects. For instance, non-uniform carburizing can lead to case depth variation, a serious defect. The case depth ($d$) as a function of time ($t$) and temperature ($T$) follows a parabolic diffusion law:

$$d^2 = 4 D t$$

Where $D$ is the temperature-dependent diffusion coefficient, given by $D = D_0 \exp(-Q_d / RT)$. A temperature variation of just ±10°C in the furnace can lead to a significant variation in $D$, and thus $d$, across a load. This is why modern practices employ sophisticated PID control algorithms:

$$u(t) = K_p e(t) + K_i \int_0^t e(\tau) d\tau + K_d \frac{de(t)}{dt}$$

Where $u(t)$ is the heater power output and $e(t)$ is the temperature error. Tuning these constants ($K_p, K_i, K_d$) is critical to minimize spatial temperature gradients that cause distortion and uneven hardness—core heat treatment defects.

Preventing distortion proactively is always superior to correcting it. Finite Element Analysis (FEA) simulation has become an indispensable tool in my work. By modeling the thermal, phase transformation, and stress-strain fields during quenching, we can predict distortion patterns. The governing thermo-elasto-plastic equations are complex:

$$\nabla \cdot (\sigma) + \rho g = 0 \quad \text{(Equilibrium)}$$

$$\sigma = C : (\epsilon – \epsilon_{th} – \epsilon_{tr} – \epsilon_{pl}) \quad \text{(Constitutive Law)}$$

$$\rho c_p \frac{\partial T}{\partial t} = \nabla \cdot (k \nabla T) + \rho L \frac{\partial f}{\partial t} \quad \text{(Heat Transfer with Latent Heat)}$$

Where $\epsilon_{th}$ is thermal strain, $\epsilon_{tr}$ is transformation strain, $\epsilon_{pl}$ is plastic strain, $f$ is phase fraction, $L$ is latent heat, and $C$ is the stiffness tensor. Simulations allow us to optimize fixturing, quenching direction, and even modify part geometry (e.g., adding sacrificial material) to counteract predicted warpage, thus designing out the heat treatment defects before the first part is ever made.

The journey from encountering a crippling heat treatment defect to implementing a robust solution is iterative. For the pinion shaft, it involved countless trials to pinpoint the exact temperature window and over-bend amount. The science provides the guiding principles, but the art lies in the adaptation to specific shop-floor conditions. Similarly, for mesh belts, material datasheets give nominal properties, but real-world performance depends on details like weld quality, the precision of link assembly, and even the operational practices such as avoiding sudden load changes when the belt is hot. Educating operators on these nuances is a crucial, often overlooked step in defect prevention. A belt, even made from 1Cr25Ni20SiZ, will fail prematurely if subjected to mechanical shock from a fallen workpiece or rapid thermal cycling from frequent furnace idling.

In conclusion, addressing heat treatment defects requires a multi-faceted, systems-level approach. For component distortion, localized thermal correction combined with stress-relief processes like shot peening offers a highly effective salvage path, turning scrap into valuable product. For the equipment itself, strategic material upgrades paired with intelligent mechanical design drastically extend service life and reliability, reducing downtime and total cost. Both stories underscore a central theme: understanding the underlying metallurgical and mechanical principles is key to transforming problems into opportunities for improvement. The formulas and tables presented here are not just academic exercises; they are the distilled essence of practical problem-solving in the relentless pursuit of quality and efficiency in thermal processing. Every heat treatment defect carries within it the seed of a lesson, and by methodically decoding these lessons, we not only save costs but also push the entire field of manufacturing towards greater precision and sustainability.