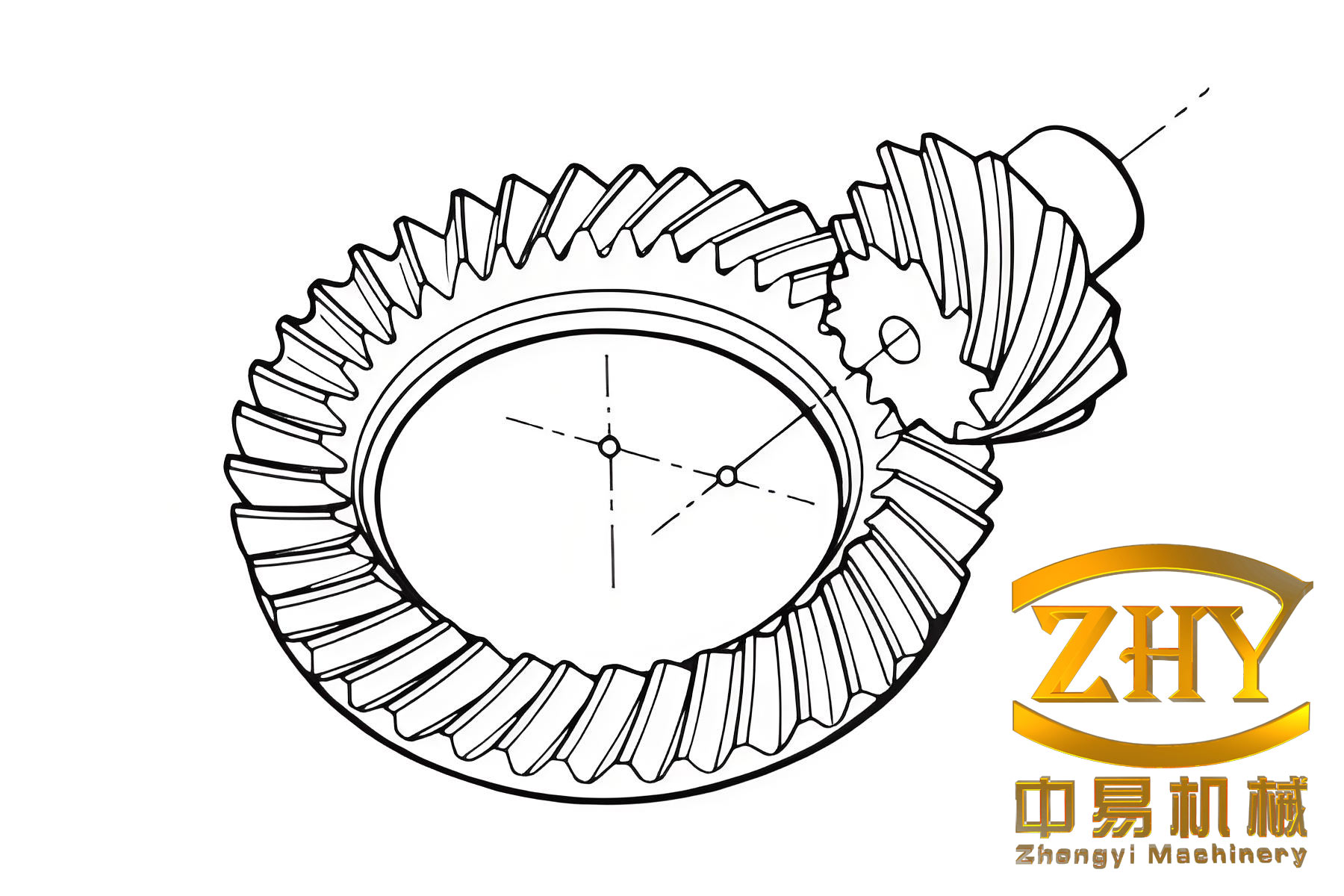

In the field of automotive transmission systems, hypoid bevel gears play a critical role due to their ability to transmit power between non-intersecting shafts with high efficiency and smooth operation. The complex geometry of hypoid bevel gear tooth surfaces demands precise manufacturing and accurate measurement to ensure optimal meshing performance. Traditional contact pattern inspection methods are increasingly inadequate for modern precision requirements, making the geometric consistency between actual and theoretical tooth surfaces a primary goal in gear quality control. This article presents a comprehensive approach for measuring tooth surface deviations in hypoid bevel gears using a one-dimensional probe, incorporating error compensation techniques to enhance accuracy. The method is designed for implementation on domestically produced CNC measurement centers, addressing the need for cost-effective and reliable measurement solutions in the industry.

The core of this methodology lies in generating theoretical tooth surface data, planning measurement grids, establishing coordinate system relationships, performing measurements with a one-dimensional probe, and applying data processing with error compensation. By leveraging principles from gear meshing theory, differential geometry, and complex surface measurement, we derive formulas for compensation and validate the approach through comparative experiments. Throughout this discussion, the term “hypoid bevel gear” will be frequently emphasized to highlight the specific application context. The integration of tables and mathematical formulations will facilitate a clear understanding of the underlying concepts and procedures.

The tooth surface of a hypoid bevel gear is a complex spatial curve that cannot be expressed by elementary functions. However, the gear generation process mimics the meshing of a hypoid bevel gear pair, where the tooth surface and the cutter surface form a pair of conjugate surfaces. Using gear meshing principles and differential geometry, the theoretical tooth surface data can be obtained through the motion relationships and fundamental equations of meshing during the cutting process. The parametric equations for the tooth surface and its unit normal vector are essential starting points. For a hypoid bevel gear pair, the tooth surface \(\mathbf{r}_i\) and unit normal vector \(\mathbf{n}_i\) can be represented as:

$$

\mathbf{r}_i = \mathbf{r}_i(u_i, \theta_i), \quad \mathbf{n}_i = \mathbf{n}_i(u_i, \theta_i) \quad \text{for } i=1,2

$$

where \(i=1\) denotes the pinion (small gear) and \(i=2\) denotes the gear (large gear). The parameters \(u_i\) and \(\theta_i\) are surface variables dependent on the cutting method. For instance, in the HFT (Hypoid Formate) cutting method, \(u_2\) represents the length variable along the cutter cone generatrix for the gear, and \(\theta_2\) is the rotation angle variable of the cutter. For the pinion, \(u_1\) and \(\theta_1\) correspond to the cutter cone rotation angle and the cradle generating rotation angle, respectively. These equations are derived through a series of coordinate transformations and kinematic analyses, which involve the cutter geometry, machine tool settings, and gear blank positioning.

To measure deviations across the entire tooth surface, a measurement grid must be planned on a topological mapping of the surface. A simple and effective mapping is the rotational projection of the tooth surface onto an axial plane. This projection facilitates the definition of a measurement region, excluding areas like fillets or root zones where probe access is limited. Standards such as those from the American Gear Manufacturers Association (AGMA) recommend grid spacing: along the face width, it should be less than 10% of the total width, and along the profile direction, less than 5% of the working tooth height but not exceeding 0.6 mm. Typically, a grid of 9 points along the face width and 5 points along the profile height (totaling 45 points) is used for hypoid bevel gears.

In the rotational projection plane, a coordinate system OXY is established, where O is the design crossing point of the gear. For any measured point \(M^*\) on the tooth surface with coordinates \((x^*, y^*)\) in this plane, its corresponding coordinates in the workpiece coordinate system \((x_i, y_i, z_i)\) satisfy the following nonlinear equations:

$$

x_i = x^*, \quad y_i^2 + z_i^2 = y^*

$$

Solving these equations yields the parameters \(u_i\) and \(\theta_i\), which are then substituted into the parametric equations to obtain the coordinates and unit normal vectors of the measurement points. Prior to measurement, theoretical coordinates must be compensated for the probe radius, as measurement machines record the center coordinates of the probe ball. This compensation ensures that the measured data aligns with the actual tooth surface geometry.

A critical aspect of the measurement process is establishing the correspondence between the workpiece coordinate system and the measurement coordinate system. On a measurement center, the gear is typically positioned using machining reference surfaces such as the基准端面 and基准孔. Once the distance from the machining reference plane to the rotary table plane (where the measurement coordinate system origin lies) is determined, the spatial relationship between the two systems is fully defined. Consider a setup on a JD45S-type gear measurement center: assuming zero distance from the machining reference plane to the rotary table, the workpiece coordinate system \(O_w X_w Y_w Z_w\) (right-handed) and the measurement coordinate system \(O_c X_c Y_c Z_c\) (left-handed) are related by a transformation matrix \(\mathbf{C}_{cw}\). This matrix accounts for the orientation and offset between the systems, and it can be expressed as:

$$

\mathbf{C}_{cw} = \begin{bmatrix}

0 & -1 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 0 & -1 & 0 \\

-1 & 0 & 0 & a \\

0 & 0 & 0 & 1

\end{bmatrix}

$$

where \(a\) is the installation distance. This transformation enables the conversion of theoretical points from the workpiece system to the measurement system, facilitating precise probe positioning.

The positioning of the tooth surface within the measurement coordinate system is pivotal for accurate deviation assessment. This involves selecting a measurement reference point on the tooth surface, where the deviation between the theoretical and actual surfaces is assumed to be zero. This point serves as an initial alignment reference, determining the relative position of the gear in the measurement system. Typically, the reference point is chosen from the middle of the measurement grid sequence to ensure consistency in output results. The procedure for locating the tooth surface involves several steps: first, orienting the one-dimensional probe so that its sensitive direction aligns approximately with the normal direction at the reference point; second, calibrating the probe; third, moving the probe to a position above the reference point; fourth, rotating the worktable to allow probe entry into the adjacent tooth space; fifth, bringing the probe into contact with the tooth surface at the reference point by rotating the worktable; and finally, recording the worktable rotation angle \(\beta\). All other measurement points must then be transformed by rotating around the \(Z_c\)-axis by angle \(\beta\), yielding new coordinates and normal directions in the measurement system.

Due to the use of a one-dimensional probe, the sensitive direction may not perfectly align with the normal direction at each measurement point, except at the reference point. To mitigate this, during measurement, the CNC system controls the rotary table to orient the normal vector of each point into the \(X_c Z_c\) plane of the measurement system. This reduces the misalignment from three-dimensional to two-dimensional, minimizing random errors and simplifying data processing. The residual angle in the \(X_c Z_c\) plane is generally small (up to about 5 degrees), allowing for effective compensation in subsequent data analysis.

Data processing is essential to convert raw measurement readings into true deviations along the tooth surface normals. The one-dimensional probe records deviations along its sensitive direction, which may not coincide with the normal direction at the contact point. Moreover, the actual contact point between the probe and the tooth surface may shift from the theoretical point due to probe geometry and misalignment. In a microscopic region, the tooth surface can be approximated as a small plane. The geometric relationship between the probe radius, the angle between the normal and probe directions, and the measurement error is derived as follows. Let \(r\) be the probe ball radius, \(\alpha\) be the angle between the normal direction and the probe sensitive direction in the \(X_c Z_c\) plane, and \(\delta\) be the error between the measurement center reading and the true normal deviation. Then, the compensation formula is:

$$

\delta = r \left( \frac{1}{\cos \alpha} – 1 \right)

$$

This equation indicates that larger probe radii or larger angles \(\alpha\) lead to greater errors \(\delta\). Therefore, selecting a small probe radius (e.g., 2 mm or 1 mm) and minimizing \(\alpha\) are crucial for accuracy. Additionally, to ensure that the probe contacts the theoretical point, the Z-coordinate in the measurement system must be adjusted based on the probe geometry and surface orientation. This compensation accounts for both directional and positional discrepancies, yielding true normal deviations that reflect the actual tooth surface geometry.

To validate the proposed measurement and data processing method, a case study was conducted on a hypoid bevel gear pair. The geometric parameters of the gears are summarized in Table 1, and the machining adjustment parameters for the pinion are provided in Table 2. The gears were cut on a Gleason No. 116 machine. Measurements were performed on a JD45S gear measurement center using a one-dimensional probe, following the procedures outlined earlier. After data acquisition and processing, the tooth surface deviations for the pinion’s convex and concave sides, as well as the toe and heel regions, were obtained. For comparison, the same gear was measured on an M&M 3525 measurement center equipped with a three-dimensional probe, ensuring similar initial conditions.

| Parameter | Gear (Large) | Pinion (Small) |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Teeth | 35 | 6 |

| Face Width (mm) | 37.00 | 42.56 |

| Root Angle (°) | 72.67 | 10.27 |

| Pitch Angle (°) | 78.60 | 10.97 |

| Face Angle (°) | 79.33 | 16.70 |

| Mounting Distance (mm) | 54.00 | 128.50 |

| Addendum (mm) | 1.21 | 10.04 |

| Dedendum (mm) | 11.18 | 2.61 |

| Offset Distance (mm) | 30.00 | |

| Crown to Crossing Point (mm) | 26.06 | 121.97 |

| Face Apex to Crossing Point (mm) | 23.59 | 81.19 |

| Root Apex to Crossing Point (mm) | 0.11 | 14.16 |

| Pitch Apex to Crossing Point (mm) | -2.02 | 18.76 |

| Face Apex to Crossing Point (mm) | -2.45 | 3.00 |

| Parameter | Concave Side | Convex Side |

|---|---|---|

| Cutter Diameter (mm) | 219.73 | 236.79 |

| Cutter Pressure Angle (°) | 14.00 | 31.00 |

| Blank Tilt Angle (°) | 354.57 | 353.97 |

| Cradle Angle (°) | 150.33 | 138.42 |

| Eccentric Angle (°) | 52.02 | 58.40 |

| Machine Tool Cutter Tilt Angle (°) | 60.62 | 63.90 |

| Machine Tool Cutter Swivel Angle (°) | 244.87 | 252.62 |

| Generating Ratio | 5.41 | 6.05 |

| Axial Work Setting (mm) | -5.52 | 10.35 |

| Vertical Work Setting (mm) | 24.40 | 35.65 |

| Machine Center Setting (mm) | 17.38 | 23.74 |

The measurement results from the one-dimensional probe, after error compensation, showed deviation trends consistent with those from the three-dimensional probe. For the convex side, deviations decreased from the toe to the heel, with the maximum positive deviation at the toe tip and the minimum negative deviation at the heel root. For the concave side, deviations increased from the toe to the heel, with the maximum positive deviation at the heel root and the minimum negative deviation at the toe tip. Quantitatively, the one-dimensional probe measurements yielded a maximum positive deviation of 0.2356 mm and a minimum negative deviation of -0.2870 mm for the convex side, and 0.3262 mm and -0.2692 mm for the concave side. In comparison, the three-dimensional probe measurements showed 0.1982 mm and -0.2366 mm for the convex side, and 0.2900 mm and -0.2136 mm for the concave side. The slight differences (approximately 0.05 mm) can be attributed to factors such as measurement machine accuracy, rotary table positioning errors, uncertainties in the distance from the reference plane to the table, grid point planning variations, and probe ball sphericity. Despite these minor discrepancies, the overall agreement validates the feasibility and accuracy of the one-dimensional probe method for hypoid bevel gear measurement.

To further elaborate on the theoretical foundations, the generation of hypoid bevel gear tooth surfaces involves complex kinematics. The coordinate transformations between the cutter, machine tool, and gear blank can be represented through homogeneous transformation matrices. For instance, the position vector of a point on the cutter surface in the cutter coordinate system is transformed to the gear blank system via a series of rotations and translations. The meshing condition is enforced using the equation of meshing, which ensures that the relative velocity between the cutter and gear blank is perpendicular to the common normal at the contact point. This condition can be expressed as:

$$

\mathbf{n} \cdot \mathbf{v}^{(12)} = 0

$$

where \(\mathbf{n}\) is the unit normal vector on the cutter surface, and \(\mathbf{v}^{(12)}\) is the relative velocity vector between the cutter and gear blank. Solving this equation along with the surface parametric equations yields the complete tooth surface model. This model is essential for generating the theoretical data used in measurement planning.

In the context of measurement grid planning, the rotational projection method simplifies the mapping of three-dimensional points to a two-dimensional plane. The coordinates \((x^*, y^*)\) in the projection plane are related to the three-dimensional coordinates through nonlinear equations that account for the gear geometry. Numerical methods, such as Newton-Raphson iteration, are employed to solve these equations for the parameters \(u_i\) and \(\theta_i\). Once these parameters are determined, the coordinates and normals are computed using the tooth surface equations. Table 3 illustrates a sample set of measurement grid points for a hypoid bevel gear, showing the diversity in positions across the tooth surface.

| Point ID | Projection Coordinates (x*, y*) (mm) | Workpiece Coordinates (x, y, z) (mm) | Unit Normal Vector (nx, ny, nz) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | (10.0, 15.0) | (10.0, 12.0, 9.0) | (0.707, 0.0, 0.707) |

| 2 | (12.0, 16.0) | (12.0, 12.8, 10.4) | (0.800, 0.0, 0.600) |

| 3 | (14.0, 17.0) | (14.0, 13.6, 11.8) | (0.866, 0.0, 0.500) |

| … | … | … | … |

| 45 | (20.0, 25.0) | (20.0, 15.0, 20.0) | (0.940, 0.0, 0.342) |

The error compensation model can be extended to account for additional factors, such as probe deflection or environmental variations. However, the primary compensation focuses on the geometric relationship described by the formula \(\delta = r (1/\cos \alpha – 1)\). This formula is derived from considering the probe ball as a sphere of radius \(r\) contacting a planar surface. When the probe sensitive direction is misaligned by an angle \(\alpha\), the measured distance along the probe direction differs from the true normal distance by \(\delta\). For small angles \(\alpha\), a Taylor series expansion approximates \(\delta \approx r \alpha^2 / 2\), highlighting the quadratic dependence on the misalignment angle. This underscores the importance of minimizing \(\alpha\) during measurement setup.

In practice, the measurement of hypoid bevel gears with a one-dimensional probe requires careful calibration and alignment. The probe must be calibrated using a reference sphere to determine its effective radius and any offsets. During measurement, the CNC system follows a predefined path to position the probe at each grid point, adjusting the worktable orientation to align the normal vector into the \(X_c Z_c\) plane. The probe then approaches the surface along its sensitive direction until contact is detected. The measured value is recorded, and subsequent data processing applies the compensation formula to compute the true deviation. This process is repeated for all points on the grid, generating a deviation map that can be used for quality assessment or feedback to the manufacturing process.

The comparative analysis between one-dimensional and three-dimensional probe measurements reveals that both methods capture the same deviation trends, but the one-dimensional probe may introduce slightly larger errors due to the compensation process and potential misalignments. However, the cost-effectiveness and availability of one-dimensional probes make this method attractive for domestic measurement centers. Future improvements could involve enhanced calibration techniques, real-time error compensation algorithms, and integration with advanced manufacturing systems for closed-loop control of hypoid bevel gear production.

In conclusion, the methodology for measuring tooth surface deviations in hypoid bevel gears using a one-dimensional probe, combined with error compensation and data processing, provides a viable and accurate solution for gear inspection. The approach encompasses theoretical data generation based on gear meshing principles, measurement grid planning, coordinate system transformations, precise positioning, and comprehensive error compensation. Validation through comparative measurements demonstrates consistency with results from three-dimensional probes, confirming the method’s reliability. This work contributes to the advancement of hypoid bevel gear measurement technology, supporting the development of domestic measurement capabilities and promoting precision manufacturing in the automotive and machinery industries. The frequent emphasis on hypoid bevel gears throughout this discussion underscores their significance in modern transmission systems and the ongoing need for innovative measurement solutions.