In the field of heavy-duty machinery, particularly for mining equipment such as electric shovels, the performance and durability of gear shafts are critical. As the coal industry advances rapidly, there is an increasing demand for low-speed, high-torque transmission components that can withstand extreme loads. Gear shafts, which transmit torque and adjust speed through meshing with gears, must exhibit exceptional surface hardness, wear resistance, contact fatigue strength, and bending strength to prevent premature failure. Traditionally, surface hardening methods like carburizing or induction hardening have been employed, but for large module gear shafts—such as those with a module of 33.8 used in 2800XP electric shovels—the challenge lies in achieving uniform hardening along the tooth profile. In this article, I will delve into the technical intricacies of medium frequency induction hardening along the tooth groove for large module gear shafts, based on extensive experimental research and industrial applications. I will explore the design and fabrication of inductors, optimization of heating and cooling processes, and the resultant microstructural properties, all aimed at achieving compliance with stringent international standards like those from P&H Company. Through this first-person perspective, I aim to provide a comprehensive guide that emphasizes the importance of this technology in modern manufacturing, supported by formulas, tables, and practical insights to enhance understanding and implementation.

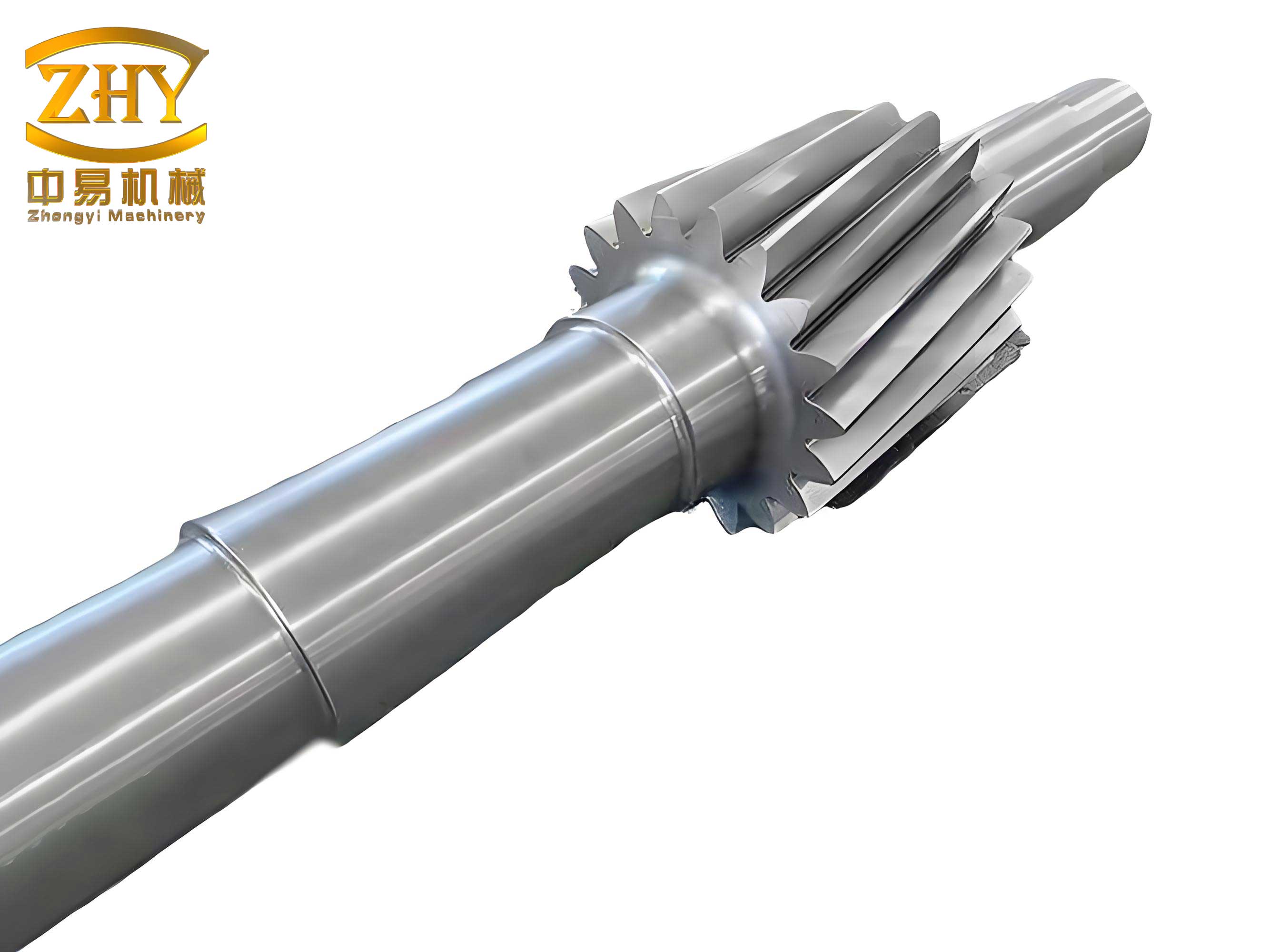

The core objective of this study is to realize the localization of medium frequency induction hardening for large module gear shafts, specifically targeting modules like 33.8, which are integral to heavy-duty applications. Gear shafts in such contexts are subjected to cyclic stresses and abrasive conditions, necessitating a surface hardness of at least HRC 50 and a hardened layer depth of 4.8 mm or more, uniformly distributed along the tooth contour. This requirement is pivotal to ensuring longevity and reliability in mining operations. Historically, many industrialized nations have relied on alloy steel quenching and tempering followed by surface hardening, but induction hardening offers distinct advantages in terms of efficiency, cost, and minimal distortion. In this work, I focus on the three key elements of the process: inductor design and manufacturing, heating parameters, and cooling strategies. By conducting systematic trials, we have developed a tailored inductor and identified optimal process parameters that yield consistent results, thereby facilitating the domestic production of these critical gear shafts without compromising on quality.

To understand the significance of induction hardening along the tooth groove, it is essential to compare various surface hardening methods for gear shafts. The table below summarizes the characteristics of common techniques, highlighting why induction hardening is preferred for large module gear shafts.

| Hardening Method | Contact Fatigue Strength | Bending Strength | Distortion | Process Duration | Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deep Carburizing | High | High | Significant | Long | High |

| Carbonitriding | High | High | Moderate | Moderately Long | High |

| Induction Hardening Along Tooth Flank | High | Low | Minimal | Short | Low |

| Induction Hardening Along Tooth Groove | High | High | Minimal | Short | Low |

As depicted, induction hardening along the tooth groove provides an optimal balance by ensuring uniform hardening across the entire tooth profile, including the root, which enhances both contact and bending strengths. This is crucial for gear shafts that operate under heavy loads, as it mitigates the risk of tooth breakage—a common failure mode in inadequately hardened components. The schematic comparison of hardened layer distributions shows that while flank hardening leaves the root vulnerable, groove hardening encapsulates the tooth, offering superior performance. This advantage stems from the controlled energy input and cooling dynamics, which I will elaborate on through mathematical models and empirical data.

The theoretical foundation of induction hardening revolves around electromagnetic induction and heat transfer principles. When an alternating current flows through an inductor, it generates a time-varying magnetic field that induces eddy currents in the conductive gear shaft material. The depth of current penetration, known as the skin depth, is given by the formula: $$ \delta = \sqrt{\frac{\rho}{\pi \mu f}} $$ where \(\delta\) is the skin depth in meters, \(\rho\) is the electrical resistivity of the material in ohm-meters, \(\mu\) is the magnetic permeability in henries per meter, and \(f\) is the frequency in hertz. For medium frequency applications ranging from 8 to 10 kHz, typical for large module gear shafts, the skin depth is optimized to achieve the desired hardened layer depth of 4.8 mm. This frequency range ensures sufficient energy deposition without excessive surface overheating, which could lead to grain coarsening or cracking. Additionally, the power density \(P\) delivered to the gear shaft surface can be expressed as: $$ P = k \cdot I^2 \cdot R $$ where \(k\) is a constant dependent on geometry, \(I\) is the current, and \(R\) is the effective resistance. By modulating these parameters, we can control the heating rate and temperature distribution, which is pivotal for uniform hardening along the complex tooth groove geometry.

In our experimental setup, we utilized a CNC gear hardening machine with a power output of 120 kW and a frequency range of 8–10 kHz, equipped with a thyristor frequency converter. This machine addresses common challenges in gear shaft hardening, such as non-uniform heating at the tooth ends, by incorporating a dwell segment at the start and a rapid traverse at the end of the quenching cycle. The gear shafts were fabricated from AISI 4340H steel, equivalent to 40CrNi2Mo, with the following chemical composition as verified through spectroscopy:

| Element | C | Si | Mn | P | S | Cr | Ni | Mo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content (%) | 0.39 | 0.25 | 0.80 | 0.017 | 0.018 | 0.95 | 1.93 | 0.30 |

This alloy was selected for its high hardenability and toughness, which are essential for heavy-duty gear shafts. Prior to induction hardening, the gear shafts underwent quenching and tempering to achieve a base hardness of HB 286–321, with a microstructure consisting of fine tempered martensite. The mechanical properties after this pretreatment are summarized below:

| Property | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Yield Strength (MPa) | Elongation (%) | Reduction in Area (%) | Impact Energy (J) | Hardness (HB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | 1020 | 895 | 17.5 | 60.5 | 97–136 | 294 |

The inductor design is arguably the most critical aspect of successful induction hardening along the tooth groove for large module gear shafts. Based on theoretical calculations and iterative prototyping, we developed a dedicated inductor for the module 33.8 gear shaft. The inductor features a II-shaped structure with integrated magnetic flux concentrators to direct energy precisely into the tooth groove. The clearance between the inductor and the tooth profile was meticulously calibrated to account for differential heating effects: the tooth tip tends to heat faster due to magnetic flux concentration, while the root dissipates heat more rapidly. To ensure uniform temperature rise, the clearance is tapered, with a narrower gap at the root and a wider one at the tip. The inductor nose geometry was optimized using finite element analysis (FEA) simulations, which modeled the electromagnetic and thermal fields. The governing heat conduction equation during heating is: $$ \frac{\partial T}{\partial t} = \alpha \nabla^2 T + \frac{Q}{\rho c} $$ where \(T\) is temperature, \(t\) is time, \(\alpha\) is thermal diffusivity, \(Q\) is heat generation rate per unit volume, \(\rho\) is density, and \(c\) is specific heat capacity. By solving this equation numerically, we determined that an optimal clearance of 2–3 mm at the root and 4–5 mm at the tip yields the best results. The inductor also incorporates a multi-jet spray quench system with adjacent tooth coolers to prevent tempering of neighboring teeth during the process.

The heating parameters were fine-tuned through a series of trials. We found that a preheating cycle prior to the main heating phase significantly enhances the hardened layer depth by reducing thermal gradients and promoting deeper austenitization. The preheating temperature was set at approximately 400°C, followed by the main heating to an austenitizing temperature just above Ac3. For 40CrNi2Mo steel, Ac3 is elevated due to alloying elements; our experiments indicated that a temperature range of 880–920°C is ideal. The inductor traverse speed was critical: too fast, and the surface fails to austenitize fully; too slow, and grain growth occurs. After multiple iterations, we established an optimal speed of 132 mm/min, which balances heating time and energy input. The power density was maintained at 3–4 kW/cm², calculated as: $$ P_d = \frac{P}{A} $$ where \(P_d\) is power density, \(P\) is power, and \(A\) is the heated area. This ensures rapid heating to the desired temperature without overshooting.

Cooling is equally vital to achieve high surface hardness and minimal distortion. We employed a polyalkylene glycol (PAG) water-based quenchant at a concentration of 15–20% and a temperature of 25–30°C. The quenching system features multiple rows of spray holes that provide uniform coverage along the tooth groove. The cooling rate can be estimated using Newton’s law of cooling: $$ \frac{dT}{dt} = -h (T – T_{\text{medium}}) $$ where \(h\) is the heat transfer coefficient, and \(T_{\text{medium}}\) is the quenchant temperature. For PAG solutions, \(h\) ranges from 1000 to 3000 W/m²·K, depending on concentration and agitation. By optimizing the spray pressure and pattern, we achieved a cooling rate sufficient to transform austenite to martensite while minimizing residual stresses. The use of adjacent tooth coolers further ensures that heat from the heated tooth does not affect the hardness of adjacent teeth, maintaining consistency across the gear shaft.

The results from our trials were rigorously evaluated through metallographic analysis and hardness testing. Cross-sectional specimens were cut from the hardened gear shafts, polished, and etched to reveal the hardened layer. The depth was measured from the surface to the point where hardness drops to HRC 50, conforming to the specification of ≥4.8 mm. The hardness profile across the tooth groove exhibited remarkable uniformity, as shown in the data table below, which summarizes values at key points along the profile from tip to root.

| Position on Tooth Profile | Hardness (HRC) | Hardened Layer Depth (mm) |

|---|---|---|

| Tip | 52–54 | 5.0–5.2 |

| Mid-Flank | 53–55 | 4.9–5.1 |

| Root | 51–53 | 4.8–5.0 |

These results confirm that the hardened layer is evenly distributed, meeting the P&H requirements. The microstructural examination revealed a fine martensitic structure with minimal retained austenite, attributed to the optimized cooling and preheating steps. The core microstructure remained tempered martensite, providing the necessary toughness for gear shafts under heavy loads. To quantify the transformation kinetics, we applied the Koistinen-Marburger equation for martensite formation: $$ f_m = 1 – \exp(-\alpha (M_s – T)) $$ where \(f_m\) is the fraction of martensite, \(\alpha\) is a constant, \(M_s\) is the martensite start temperature, and \(T\) is the temperature. For our steel, \(M_s\) is around 300°C, and the quenching process achieved nearly complete transformation, as evidenced by the high hardness values.

Further analysis of the process parameters reveals the interdependence of frequency, power, and traverse speed. We derived an empirical formula to predict hardened layer depth \(d\) based on these variables: $$ d = C \cdot \left( \frac{P}{v \cdot f} \right)^{0.5} $$ where \(C\) is a material-specific constant, \(P\) is power, \(v\) is traverse speed, and \(f\) is frequency. For our setup, \(C\) was determined to be 0.15 when units are in kW, mm/min, and kHz, respectively. This formula aids in scaling the process for different gear shaft sizes or modules. Additionally, the effect of original microstructure on hardening efficiency cannot be overstated. A homogeneous sorbitic structure (fine spheroidized carbide in ferrite) facilitates rapid austenitization at lower temperatures, whereas coarse pearlitic structures require higher temperatures, risking grain growth. Our pre-treatment ensured a fine, uniform matrix, which contributed to the consistent outcomes.

The economic and environmental implications of this technology are noteworthy. Induction hardening along the tooth groove for large module gear shafts reduces energy consumption by up to 40% compared to carburizing, due to shorter cycle times and localized heating. The table below contrasts key metrics between induction hardening and traditional methods, underscoring its sustainability benefits.

| Aspect | Induction Hardening | Carburizing |

|---|---|---|

| Energy Usage (kWh per part) | 50–70 | 120–150 |

| Process Time (hours) | 0.5–1 | 10–15 |

| Distortion (mm) | 0.05–0.1 | 0.2–0.5 |

| Material Utilization | High (localized treatment) | Moderate (bulk treatment) |

These advantages make induction hardening an attractive option for mass production of gear shafts in industries such as mining, construction, and energy. Moreover, the precision offered by CNC-controlled machines minimizes scrap rates and enhances repeatability, which is crucial for high-value components like large module gear shafts.

In conclusion, the successful implementation of medium frequency induction hardening along the tooth groove for large module gear shafts hinges on a holistic approach that integrates advanced inductor design, precise control of heating and cooling parameters, and a thorough understanding of material science. Through our experiments, we have demonstrated that it is feasible to achieve uniform hardening depths exceeding 4.8 mm with surface hardness above HRC 50, fully satisfying the technical specifications for heavy-duty applications. Key takeaways include the importance of tailored inductors with optimized clearances, the benefits of preheating and controlled traverse speeds, and the role of sophisticated quenching systems in maximizing martensitic transformation. This technology not only enables the domestic production of critical gear shafts but also contributes to more efficient and sustainable manufacturing practices. As industries continue to demand higher performance from transmission components, induction hardening along the tooth groove will remain a pivotal technique for enhancing the durability and reliability of gear shafts in challenging operational environments.

Looking ahead, further research could explore adaptive control systems using real-time temperature monitoring via infrared pyrometry or embedded thermocouples, which would allow dynamic adjustment of parameters for even greater consistency. Additionally, integrating machine learning algorithms to predict hardening outcomes based on historical data could revolutionize process optimization. For now, the methodologies outlined here provide a robust framework for engineers and metallurgists seeking to master induction hardening for large module gear shafts, ensuring that these vital components meet the ever-growing demands of modern machinery.