In the field of power transmission, worm drives represent a critical class of components where the meshing configuration fundamentally dictates performance. This has spurred continuous research into novel screw gear designs. I propose an innovative configuration that synthesizes the advantages of two promising concepts: the rolling-contact characteristic of roller-enveloping worm drives and the multi-tooth, backlash-free engagement of end-face meshing worm drives. This new design is termed the Roller Enveloping End-Face Engagement Worm Drive. The core idea is to transform sliding friction at the primary meshing interface into rolling friction, thereby aiming to significantly reduce wear, minimize heat generation, and enhance efficiency and service life, while simultaneously achieving high load capacity through multi-tooth contact.

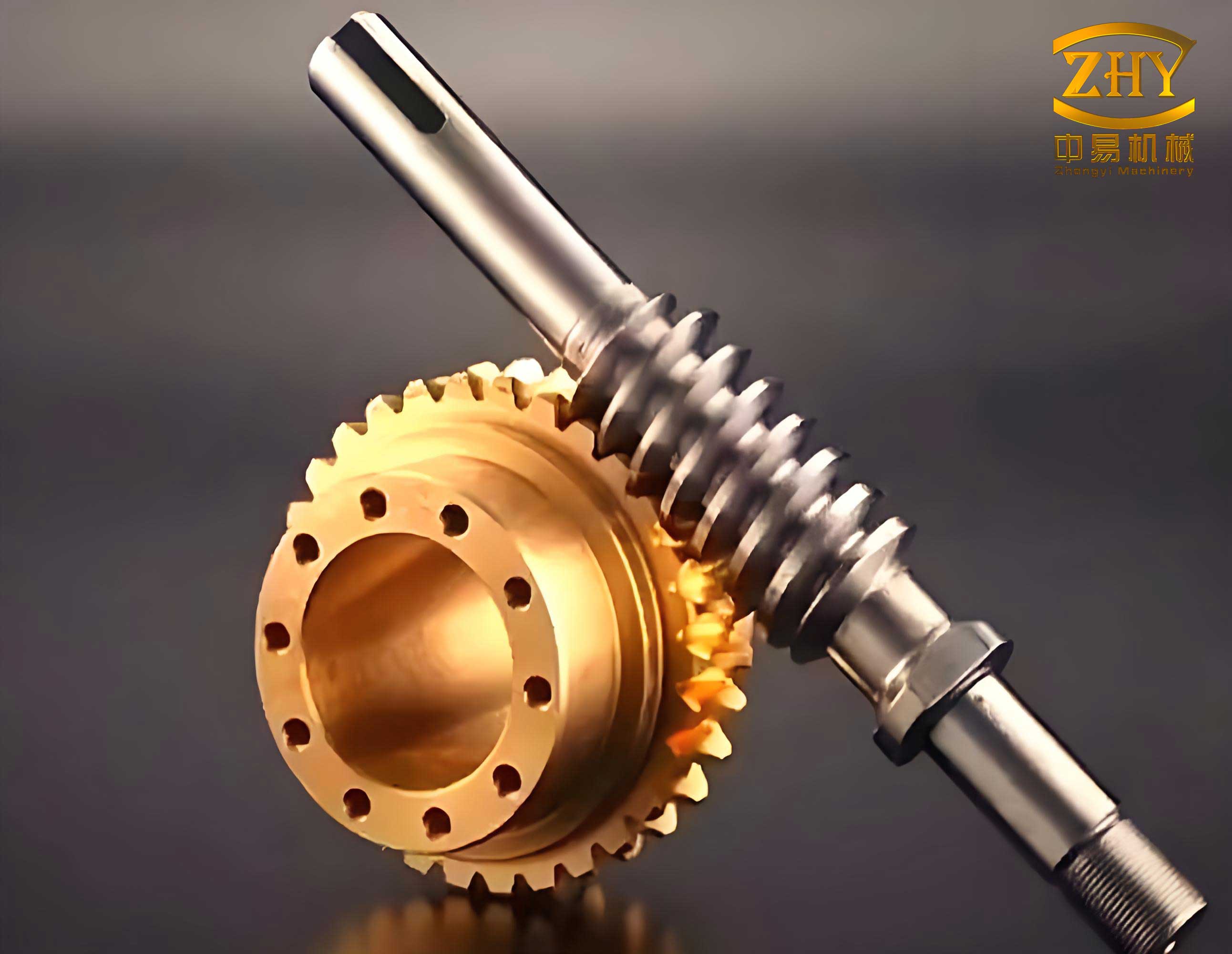

The operational principle of this screw gear system is foundational. As illustrated, the drive consists of a worm shaft, two separate worm segments mounted on the left and right sides of this shaft, and a worm wheel. The worm wheel teeth are not conventional gear teeth but are instead cylindrical rollers capable of rotating about their own axes, often supported by needle bearings to further reduce internal friction. In operation, the worm acts as the driving member. The left worm segment engages the upper flanks of the worm wheel rollers, while the right worm segment engages the lower flanks. This symmetrical, dual-sided engagement ensures constant contact regardless of rotational direction, effectively eliminating backlash and its associated positional error. This configuration marks a significant departure from traditional single-engagement worm drives, directly addressing challenges related to precision and smoothness in motion control applications involving screw gear mechanisms.

The forming principle of the worm thread surface is equally distinctive. Unlike a conventional cylindrical or hourglass worm, the thread profile on each worm segment is generated by the envelope of the roller family. Conceptually, if one considers a roller’s cylindrical surface as a tool, the surface traced by this tool as it moves in meshing motion relative to the worm blank defines the conjugate worm flank. The critical aspect here is the end-face engagement geometry. While traditional enveloping worm drives engage teeth along a plane roughly perpendicular to the worm wheel axis, this end-face configuration engages teeth in a plane parallel to the worm wheel axis. This orientation dramatically increases the number of simultaneously engaged tooth pairs. For a given worm wheel diameter and module, end-face engagement can engage nearly half the circumference of the wheel at any instant, compared to only a few teeth in a standard design. This directly translates to superior load distribution and higher torque capacity for this specialized type of screw gear.

Mathematical Modeling and Coordinate System Establishment

A rigorous mathematical model is essential for analyzing the meshing characteristics of this roller enveloping end-face engagement worm drive. The foundation of this model lies in establishing a series of coordinate systems based on differential geometry principles.

First, we define the fixed and moving coordinate frames:

- $\sigma_1 (O_1; \mathbf{i}_1, \mathbf{j}_1, \mathbf{k}_1)$: Fixed coordinate system attached to the worm housing.

- $\sigma_2 (O_2; \mathbf{i}_2, \mathbf{j}_2, \mathbf{k}_2)$: Fixed coordinate system attached to the worm wheel housing. The origins $O_1$ and $O_2$ are separated by the center distance $A$ along $\mathbf{i}_2$.

- $\sigma_1′ (O_1′; \mathbf{i}_1′, \mathbf{j}_1′, \mathbf{k}_1′)$: Moving coordinate system rigidly connected to the worm. $\mathbf{k}_1’$ is the worm’s axis of rotation.

- $\sigma_2′ (O_2′; \mathbf{i}_2′, \mathbf{j}_2′, \mathbf{k}_2′)$: Moving coordinate system rigidly connected to the worm wheel. $\mathbf{k}_2’$ is the worm wheel’s axis of rotation.

- $\sigma_0 (O_0; \mathbf{i}_0, \mathbf{j}_0, \mathbf{k}_0)$: Coordinate system fixed to an individual roller, with its origin at the center of the roller’s cylindrical face.

The worm rotates with angular velocity $\boldsymbol{\omega}^{(1)} = \omega_1 \mathbf{k}_1’$, and the worm wheel rotates with $\boldsymbol{\omega}^{(2)} = \omega_2 \mathbf{k}_2’$. Their relationship is defined by the transmission ratio $i_{12} = \omega_1 / \omega_2 = Z_2 / Z_1$, where $Z_1$ is the number of worm threads and $Z_2$ is the number of rollers on the worm wheel. The rotation angles are $\varphi_1$ and $\varphi_2$, with $\varphi_2 = i_{21} \varphi_1$ and $i_{21} = 1/i_{12}$.

The cylindrical surface of a roller in its local frame $\sigma_0$ is given by the vector equation:

$$ \mathbf{r}_0 = \begin{bmatrix} x_0 \\ y_0 \\ z_0 \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} R \cos\theta \\ R \sin\theta \\ u \end{bmatrix} $$

where $R$ is the roller radius, $u$ is the axial parameter along the roller, and $\theta$ is the angular parameter around the roller’s circumference.

To analyze contact conditions, an activity frame $\sigma_p (O_p; \mathbf{e}_1, \mathbf{e}_2, \mathbf{n})$ is established at the potential contact point $P$ on the roller surface. Here, $\mathbf{n}$ is the unit normal to the roller surface, $\mathbf{e}_1$ is along the surface’s $u$-parameter direction (axial), and $\mathbf{e}_2$ is along the $\theta$-parameter direction (circumferential). For a cylinder:

$$ \mathbf{n} = \begin{bmatrix} \cos\theta \\ \sin\theta \\ 0 \end{bmatrix}, \quad \mathbf{e}_1 = \begin{bmatrix} 0 \\ 0 \\ 1 \end{bmatrix}, \quad \mathbf{e}_2 = \begin{bmatrix} -\sin\theta \\ \cos\theta \\ 0 \end{bmatrix}. $$

The transformation matrices between these coordinate systems are crucial. The transformations from moving to fixed frames involve simple rotations:

$$ \mathbf{M}_{1’1} = \begin{bmatrix} \cos\varphi_1 & -\sin\varphi_1 & 0 & 0 \\ \sin\varphi_1 & \cos\varphi_1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix}, \quad \mathbf{M}_{2’2} = \begin{bmatrix} \cos\varphi_2 & -\sin\varphi_2 & 0 & 0 \\ \sin\varphi_2 & \cos\varphi_2 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix}. $$

The transformation from the worm moving frame $\sigma_1’$ to the worm wheel moving frame $\sigma_2’$ accounts for the spatial relationship and is given by:

$$ \mathbf{M}_{2’1′} = \mathbf{M}_{2’2}\mathbf{M}_{21}\mathbf{M}_{11′} = \begin{bmatrix} -\cos\varphi_1\cos\varphi_2 & \sin\varphi_1\cos\varphi_2 & -\sin\varphi_2 & A\cos\varphi_2 \\ \cos\varphi_1\sin\varphi_2 & -\sin\varphi_1\sin\varphi_2 & -\cos\varphi_2 & -A\sin\varphi_2 \\ -\sin\varphi_1 & -\cos\varphi_1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix}. $$

Finally, the transformation from $\sigma_2’$ to the activity frame $\sigma_p$ is:

$$ \mathbf{A}_{2’p} = \begin{bmatrix} 0 & -1 & 0 \\ -\sin\theta & 0 & \cos\theta \\ \cos\theta & 0 & \sin\theta \end{bmatrix}. $$

These transformations allow us to express all vectors and velocities in a common frame for meshing analysis.

Derivation of Relative Kinematics and Meshing Function

The analysis of any screw gear’s performance hinges on understanding the relative motion at the contact point. Let $\mathbf{r}_0$ be the position vector of point $P$ in $\sigma_0$. Its expressions in $\sigma_2’$ and $\sigma_1’$ are $\mathbf{r}_{2′}$ and $\mathbf{r}_{1′}$, respectively. The relative velocity of the worm surface (1′) with respect to the roller surface (2′) at point $P$ is:

$$ \mathbf{v}^{(1’2′)} = \frac{d\boldsymbol{\xi}}{dt} + \boldsymbol{\omega}^{(1’2′)} \times \mathbf{r}_{1′} – \boldsymbol{\omega}^{(2′)} \times \boldsymbol{\xi}, $$

where $\boldsymbol{\xi} = A\mathbf{i}_2$ is the center distance vector, and $\boldsymbol{\omega}^{(1’2′)} = \boldsymbol{\omega}^{(1′)} – \boldsymbol{\omega}^{(2′)}$ is the relative angular velocity.

Projecting these vectors into the activity frame $\sigma_p$ is necessary for applying the meshing condition. After coordinate transformations and algebraic manipulation, the components of the relative velocity in $\sigma_p$ are found to be:

$$

\begin{aligned}

v^{(1’2′)}_1 &= -B_2 \sin\theta + B_3 \cos\theta, \\

v^{(1’2′)}_2 &= -B_1, \\

v^{(1’2′)}_n &= B_2 \cos\theta + B_3 \sin\theta,

\end{aligned}

$$

where $B_1, B_2, B_3$ are functions of the geometric parameters $(a_2, b_2, c_2)$ defining the roller center in $\sigma_2$, the roller parameters $(u, \theta, R)$, the center distance $A$, the rotation angles $(\varphi_1, \varphi_2)$, and the transmission ratio $i_{21}$.

Similarly, the relative angular velocity components in $\sigma_p$ are:

$$

\begin{aligned}

\omega^{(1’2′)}_1 &= \cos\varphi_2 \sin\theta – i_{21} \cos\theta, \\

\omega^{(1’2′)}_2 &= \sin\varphi_2, \\

\omega^{(1’2′)}_n &= -\cos\theta \cos\varphi_2 – i_{21} \sin\theta.

\end{aligned}

$$

The fundamental equation of meshing for conjugate surfaces states that for contact to be maintained, the relative velocity must have no component along the common normal to the surfaces at the contact point. This is expressed as:

$$ \Phi = \mathbf{n} \cdot \mathbf{v}^{(1’2′)} = v^{(1’2′)}_n = 0. $$

Substituting the expression for $v^{(1’2′)}_n$ yields the meshing function specific to this roller enveloping end-face engagement screw gear:

$$ \Phi = M_1 \cos\varphi_2 + M_2 \sin\varphi_2 + M_3 = 0, $$

where

$$

\begin{aligned}

M_1 &= \sin\theta (a_2 – u), \\

M_2 &= 0, \\

M_3 &= -i_{21}\cos\theta (a_2 – u) – A \sin\theta.

\end{aligned}

$$

The simplification $M_2=0$ is a particular feature arising from the end-face engagement geometry and the chosen coordinate setup. The meshing equation $\Phi(u, \theta, \varphi_2)=0$ establishes a critical relationship between the roller surface parameters $(u, \theta)$ and the wheel rotation angle $\varphi_2$ for which contact occurs.

Contact Lines, Worm Thread Surface, and Key Meshing Characteristics

For a given instant (fixed $\varphi_2$), the set of points on the roller surface that satisfy the meshing equation forms the instantaneous contact line. The contact line on the roller is therefore defined by the system:

$$ \begin{cases}

\mathbf{r}_0 = [R\cos\theta,\ R\sin\theta,\ u]^T, \\

u = f(\theta, \varphi_2) = \dfrac{P_1}{P_2} \quad \text{(derived from } \Phi=0\text{)}, \\

\varphi_2 = \text{constant}.

\end{cases} $$

Analysis shows that for this drive, the contact line is very close to a straight line on the cylindrical roller. Furthermore, due to the end-face configuration, multiple rollers (often five or more pairs) are in simultaneous contact with a single worm segment, a key advantage for load sharing in this screw gear design.

The worm thread surface $\Sigma_1$ is the envelope of the family of roller surfaces $\Sigma_2$ in the worm coordinate system $\sigma_1’$. Its equation is obtained by transforming the roller surface point $\mathbf{r}_0$ into $\sigma_1’$, while ensuring the meshing condition holds:

$$ \mathbf{r}_{1′} = \mathbf{M}_{1’2′}\mathbf{r}_{2′} = \mathbf{M}_{1’2′}\mathbf{M}_{2’0}\mathbf{r}_0, \quad \text{subject to} \quad \Phi(u, \theta, \varphi_2)=0 \quad \text{and} \quad \varphi_2 = i_{21}\varphi_1. $$

The explicit form is:

$$

\begin{aligned}

x_{1′} &= -\cos\varphi_1\cos\varphi_2(a_2 – u) + \cos\varphi_1\sin\varphi_2 (R\cos\theta) – (R\sin\theta)\sin\varphi_1 + A\cos\varphi_1, \\

y_{1′} &= \sin\varphi_1\cos\varphi_2(a_2 – u) – \sin\varphi_1\sin\varphi_2 (R\cos\theta) – (R\sin\theta)\cos\varphi_1 – A\sin\varphi_1, \\

z_{1′} &= -\sin\varphi_2(a_2 – u) – \cos\varphi_2 (R\cos\theta),

\end{aligned}

$$

with $u$ determined from $\Phi=0$. This complex surface is the defining geometry of the worm in this novel screw gear pair.

To evaluate the drive’s performance, several advanced meshing characteristics are derived using the activity frame method. These are key differentiators for this roller-based, end-face engagement screw gear.

1. Induced Normal Curvature ($k_\sigma^{(1’2′)}$):

This measure indicates the conformity between the contacting surfaces. Lower absolute values suggest better conformity and lower contact stress. For this drive, it is given by:

$$ k_\sigma^{(1’2′)} = -k_\sigma^{(2’1′)} = -\frac{ \left( \omega_2^{(1’2′)} + v_1^{(1’2′)}/R \right)^2 + \left( \omega_1^{(1’2′)} \right)^2 }{\Psi}, $$

where $\Psi$ is a non-zero expression related to the derivative of the meshing function. Analysis reveals that for typical parameters, the induced curvature remains within a favorable low range of approximately $0.079 \, \text{mm}^{-1}$ to $0.17 \, \text{mm}^{-1}$ over a full wheel rotation. Compared to a traditional double-enveloping worm gear with similar parameters (having curvature around $0.2 \, \text{mm}^{-1}$), this represents a significant reduction of $0.03$ to $0.121 \, \text{mm}^{-1}$, promising lower contact stresses and improved durability for this screw gear.

| Characteristic | Roller Enveloping End-Face Worm Drive | Traditional Double-Enveloping Worm Gear (Similar Size) | Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Induced Normal Curvature | 0.079 – 0.17 mm⁻¹ | ~0.2 mm⁻¹ | Better conformity, lower contact stress. |

| Lubrication Angle ($\mu$) | ~89° – 90° | ~80° – 88° | Superior conditions for formation of elastohydrodynamic lubricant film. |

| Relative Entrainment Velocity ($V_{jx}$) | 10 – 23 mm/s | Varies widely, often lower | Promotes effective lubricant entrainment into the contact zone. |

| Roller Self-Rotation Angle ($\mu_{z0}$) | 84.5° – 90° | ~76° | More favorable alignment for inducing roller spin, enhancing rolling over sliding. |

| Simultaneous Tooth Pairs | High (e.g., 5+) | Low (typically 1-3) | Higher load capacity and smoother torque transmission. |

2. Lubrication Angle ($\mu$):

This is the angle between the relative velocity vector $\mathbf{v}^{(1’2′)}$ and the tangent to the contact line. An angle close to 90° is optimal for lubricant entrainment into the contact zone, promoting elastohydrodynamic lubrication (EHL). For this drive:

$$ \mu = \arcsin\left( \frac{ -v_1^{(1’2′)}(v_1^{(1’2′)}/R – \omega_2^{(1’2′)}) + v_2^{(1’2′)}\omega_1^{(1’2′)} }{ \sqrt{(v_1^{(1’2′)})^2 + (v_2^{(1’2′)})^2} \sqrt{(v_1^{(1’2′)}/R – \omega_2^{(1’2′)})^2 + (\omega_1^{(1’2′)})^2} } \right). $$

Calculations show $\mu$ remains remarkably stable between 89° and 90° throughout the mesh cycle, exceeding the typical 80°-88° range of a comparable traditional worm gear. This indicates excellent inherent lubrication conditions in this screw gear design.

3. Relative Entrainment Velocity ($V_{jx}$):

This velocity, the average of the surface velocities of the two bodies along the contact normal, is crucial for forming a separating EHL film. A higher $V_{jx}$ is generally beneficial. It is calculated as:

$$ V_{jx} = \frac{1}{2} \left( V_{1’\sigma} + V_{2’\sigma} \right), $$

where $V_{1’\sigma}$ and $V_{2’\sigma}$ are the projections of the absolute velocities of the worm and roller surfaces onto the contact line normal direction. For the proposed drive, $V_{jx}$ varies between 10 and 23 mm/s, which is conducive to generating a protective lubricant film under typical operating conditions.

4. Roller Self-Rotation Angle ($\mu_{z0}$):

A key advantage of using rollers as worm wheel “teeth” is their ability to spin, converting sliding to rolling friction. The propensity for self-rotation is assessed by the angle $\mu_{z0}$ between the relative velocity vector and the roller’s axis ($\mathbf{k}_0$). An angle near 90° is most favorable. It is given by:

$$ \mu_{z0} = \arccos\left( \frac{\mathbf{k}_0 \cdot \mathbf{v}^{(12)}}{|\mathbf{v}^{(12)}|} \right) = \arccos\left( \frac{v_2^{(12)}}{\sqrt{(v_1^{(12)})^2 + (v_2^{(12)})^2}} \right). $$

Analysis confirms that $\mu_{z0}$ ranges from 84.5° to 90° for this end-face engagement geometry, which is a significant 8.5° to 14° improvement over the self-rotation angle in a comparable non-end-face, roller-enveloping worm drive. This strongly suggests a more effective realization of the rolling-contact principle within this specific screw gear architecture.

Discussion and Implications

The theoretical analysis presented substantiates the potential of the roller enveloping end-face engagement worm drive as a high-performance screw gear solution. The synthesis of end-face engagement and rolling contact yields a system with distinct advantages over conventional designs.

The multi-tooth engagement inherent to the end-face configuration directly addresses the primary limitation of low contact ratio in standard worm gears. By engaging a significant portion of the worm wheel circumference, load is distributed across many rollers, drastically reducing stress on individual components and increasing the overall torque capacity and life of the screw gear assembly.

The transformation of the meshing interface from sliding to rolling friction is the other pivotal achievement. The derived kinematic parameters—particularly the high lubrication angle and favorable roller self-rotation angle—provide a strong theoretical foundation for expecting reduced friction losses, lower operating temperatures, and higher mechanical efficiency. This directly mitigates classic failure modes of worm drives such as scuffing, wear, and thermal degradation. The use of standard needle bearings for the rollers further institutionalizes rolling friction within the entire power path.

The geometric and kinematic model developed here, culminating in the worm surface equation (13), provides the complete blueprint for manufacturing the conjugate worm threads via CNC machining or precision grinding. The mathematical framework also enables sophisticated analysis of sensitivity to manufacturing errors, load distribution under deformation, and optimization of parameters like pressure angle and roller placement for a given screw gear application.

Potential applications for this advanced screw gear are found in fields demanding high precision, high load capacity, reliability, and efficiency in a compact package. These include robotics, aerospace actuators, precision machine tools, and heavy-duty positioning systems where backlash, wear, and thermal expansion are critical concerns.

In conclusion, the roller enveloping end-face engagement worm drive represents a theoretically sound and promising evolution in screw gear technology. It successfully integrates the benefits of multi-tooth contact and rolling friction into a single design. The comprehensive meshing theory establishes its favorable characteristics regarding contact conformity, lubrication, and kinematics. This work lays a essential foundation for subsequent research into detailed design protocols, experimental validation, material selection, and the full realization of this novel drive’s potential in demanding mechanical transmission systems.