In the highly competitive automotive industry, the demand for high-precision, low-noise, and long-lasting gears has become paramount. As a key component in transmissions, engines, and drive axles, gears must exhibit exceptional mechanical properties, which are largely achieved through advanced heat treatment processes. However, heat treatment defects such as internal oxidation, non-martensitic structures, and dimensional distortions often arise during carburizing, posing significant challenges to gear performance and longevity. In this article, I will delve into these common heat treatment defects, exploring their root causes and presenting effective solutions based on both traditional and innovative technologies. By leveraging data from industry practices and incorporating tables and formulas for clarity, I aim to provide a comprehensive guide to overcoming these hurdles. Throughout the discussion, the focus will remain on minimizing heat treatment defects to enhance gear reliability and efficiency.

Heat treatment defects in automotive gears primarily stem from carburizing processes, where internal oxidation leads to the formation of non-martensitic layers, and thermal stresses cause unwanted distortions. Internal oxidation occurs when oxygen penetrates the steel surface during carburizing, causing alloying elements like chromium and manganese to oxidize at grain boundaries. This reduces the local carbon concentration and hardenability, resulting in non-martensitic structures such as bainite or ferrite upon quenching. These heat treatment defects are detrimental because they lower surface hardness, introduce tensile residual stresses, and serve as initiation sites for microcracks, ultimately compromising fatigue resistance, wear performance, and gear life. For instance, studies show that non-martensitic layers exceeding 16 µm can reduce fatigue strength by approximately 25%, while layers over 40 µm may lead to a 50% reduction. Thus, addressing these heat treatment defects is critical for meeting stringent automotive standards, such as those from German manufacturers like Mercedes-Benz and BMW, which limit non-martensitic layers to 3 µm or less.

To quantify the impact of heat treatment defects, industry standards provide guidelines for non-martensitic layer thickness. The following table summarizes key requirements, highlighting the severity of these heat treatment defects and the need for precise control.

| Standard | Non-Martensitic Layer Limit | Hardness Requirement |

|---|---|---|

| GB/T 8539-2000: Grade 1 | <12 µm for case depth >0.75 mm | ≥58 HRC |

| Volkswagen | <20 µm for case depth 0.75–2.25 mm | ≥60 HRC |

| Mercedes-Benz, BMW, Porsche | ≤3 µm | ≥61 HRC |

These limits underscore the importance of mitigating heat treatment defects through advanced processes. In my experience, one effective solution is rare-earth carburizing technology, which leverages the unique properties of rare-earth elements to enhance diffusion kinetics and suppress oxidation. This approach reduces non-martensitic layers by lowering oxygen activity in the furnace atmosphere. The mechanism can be described using a simplified model for carbon diffusion with rare-earth addition: $$ \frac{\partial C}{\partial t} = D_{\text{eff}} \nabla^2 C – k_{\text{ox}}[O] $$ where \( C \) is carbon concentration, \( D_{\text{eff}} \) is the effective diffusion coefficient enhanced by rare-earth elements, \( k_{\text{ox}} \) is the oxidation rate constant, and \( [O] \) is oxygen concentration. By introducing rare-earth compounds like YF-III, oxygen is preferentially bound, reducing \( [O] \) and minimizing internal oxidation. In practice, this technology has been applied in continuous gas carburizing furnaces, where adding rare-earth flux at 20–25 mL/min improves carburizing speed by over 20% and lowers processing temperatures by 40–60°C, thereby reducing distortions and heat treatment defects. The table below illustrates typical results from rare-earth carburizing for automotive gears.

| Parameter | Without Rare-Earth | With Rare-Earth |

|---|---|---|

| Carburizing Temperature | 920°C | 890°C |

| Non-Martensitic Layer | 10–15 µm | ≤3 µm |

| Surface Hardness | 58–60 HRC | 62–64 HRC |

| Distortion Reduction | Baseline | 30–50% improvement |

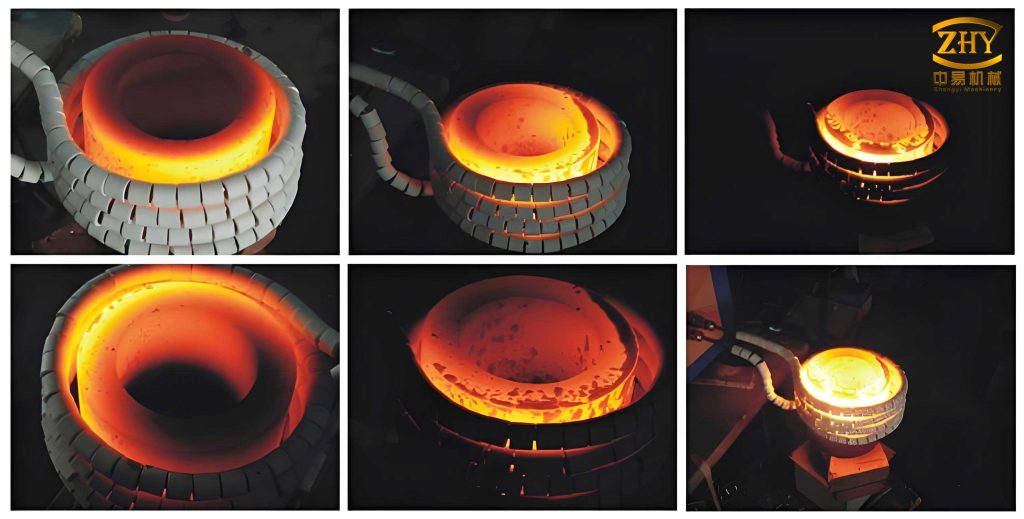

Another promising method to combat heat treatment defects is vacuum carburizing, which operates in low-pressure environments (typically 400–667 Pa) to eliminate oxidative atmospheres. Without water-gas reactions, internal oxidation is virtually absent, leading to cleaner and more uniform case layers. The process involves precise control of temperature, time, and gas flows (e.g., propane or acetylene), often modeled by equations like: $$ \text{Carbon Flux} = k_p (P_{\text{C}_3\text{H}_8} – P_{\text{eq}}) $$ where \( k_p \) is the rate constant, \( P_{\text{C}_3\text{H}_8} \) is the partial pressure of carburizing gas, and \( P_{\text{eq}} \) is the equilibrium pressure. Vacuum carburizing, combined with high-pressure gas quenching, further minimizes heat treatment defects by providing uniform cooling in inert gases like nitrogen or helium. For example, in a French ECM ICBP-966 vacuum furnace, gears made from 20CrMo steel achieved case depths of 0.82 mm with no internal oxidation, resulting in superior fatigue performance. This technology is now widely adopted in automotive plants, such as those of SAIC and FAW Group, for transmission and engine gears.

High-pressure gas quenching is particularly effective in reducing distortions, another prevalent heat treatment defect. By using gases at pressures of 1–2 MPa, cooling is more uniform than oil quenching, lowering thermal and transformational stresses. The cooling rate can be approximated by: $$ \frac{dT}{dt} = h_{\text{gas}} (T – T_{\text{gas}}) $$ where \( h_{\text{gas}} \) is the heat transfer coefficient, which increases with gas pressure and flow velocity. In practice, isothermal gas quenching—where the cooling process includes a pause to allow temperature equilibration—has shown success in controlling gear distortions. For instance, for a Ford automatic transmission ring gear (20CrMo steel), a modified quenching cycle with an 18-second fan stoppage reduced out-of-roundness to less than 0.03 mm and flatness to under 0.05 mm, meeting tight specifications. This approach mitigates heat treatment defects by avoiding rapid phase transformations that cause dimensional changes.

Beyond carburizing, post-carburizing induction hardening offers a way to address heat treatment defects by refining the microstructure and enhancing surface properties. This technique uses localized heating followed by quenching to produce hard martensitic layers with minimal distortion. The power density during induction can be expressed as: $$ P = \sigma \pi f B^2 $$ where \( \sigma \) is electrical conductivity, \( f \) is frequency, and \( B \) is magnetic flux density. By optimizing parameters, gears achieve higher hardness and better fatigue resistance. Moreover, press quenching or die quenching integrates induction with tooling to constrain parts during cooling, further reducing distortions. These methods are complemented by BH carburizing accelerators, which, like rare-earth agents, boost diffusion rates and lower processing temperatures, thereby mitigating heat treatment defects.

To systematically address distortions, which are among the most common heat treatment defects, I recommend a multi-faceted approach. First, process optimization through reduced carburizing temperatures and controlled cooling cycles is essential. Second, equipment advancements such as vacuum furnaces with high-pressure gas quenching provide superior environment control. Third, material selection plays a role; for example, using steels with higher hardenability like 20CrNiMo can reduce sensitivity to oxidation. The following formula relates distortion \( \delta \) to processing parameters: $$ \delta = \alpha \Delta T + \beta \sigma_{\text{res}} $$ where \( \alpha \) is thermal expansion coefficient, \( \Delta T \) is temperature gradient, and \( \sigma_{\text{res}} \) is residual stress. By minimizing these factors through techniques like rare-earth carburizing or vacuum processing, heat treatment defects can be kept in check.

In conclusion, heat treatment defects in automotive gears, including internal oxidation, non-martensitic structures, and distortions, pose significant challenges but are manageable through advanced technologies and careful process design. Rare-earth carburizing, vacuum carburizing, high-pressure gas quenching, and induction hardening have proven effective in mitigating these heat treatment defects, leading to gears with enhanced durability, precision, and performance. As the automotive industry continues to evolve, ongoing research into novel heat treatment methods will be crucial for further reducing heat treatment defects and meeting ever-tighter specifications. By prioritizing these solutions, manufacturers can ensure their gears withstand the demands of modern vehicles, ultimately contributing to safer, quieter, and more efficient transportation systems.

To reinforce the importance of controlling heat treatment defects, I have compiled additional data on the relationship between non-martensitic layer thickness and fatigue life reduction, based on empirical studies. This highlights the critical need for proactive measures in gear manufacturing.

| Non-Martensitic Layer Thickness (µm) | Fatigue Strength Reduction (%) | Typical Gear Life Impact |

|---|---|---|

| ≤3 | <5 | Negligible |

| 10–15 | 15–20 | Moderate, may cause early failure |

| 16–30 | 25–35 | Significant, requires rework |

| >40 | ≥50 | Severe, often leads to rejection |

Furthermore, the economic impact of heat treatment defects cannot be overlooked. Defective gears lead to increased scrap rates, warranty claims, and downtime, all of which drive up costs. By investing in technologies like vacuum carburizing or rare-earth additives, manufacturers can reduce these heat treatment defects and achieve long-term savings. For example, a shift from oil quenching to high-pressure gas quenching eliminates the need for cleaning agents and reduces energy consumption by up to 20%, as shown in some production lines. This aligns with the broader industry trend toward green manufacturing and sustainability.

In my practice, I have also explored the use of computational modeling to predict and prevent heat treatment defects. Software tools simulate carburizing profiles and distortion patterns, allowing for pre-emptive adjustments. For instance, the carbon profile after carburizing can be modeled using Fick’s second law: $$ \frac{\partial C}{\partial t} = D \frac{\partial^2 C}{\partial x^2} $$ where \( D \) is the diffusion coefficient, which varies with temperature and composition. By integrating such models with real-time furnace data, processes can be optimized to minimize heat treatment defects. This proactive approach is especially valuable for complex gear geometries, where traditional trial-and-error methods are time-consuming and costly.

Ultimately, the battle against heat treatment defects is ongoing, but with the strategies outlined here—ranging from chemical additives to advanced equipment—the automotive industry can continue to produce gears that meet the highest standards. I encourage engineers and technicians to stay informed about emerging technologies and to prioritize continuous improvement in their heat treatment practices. By doing so, we can collectively reduce the incidence of heat treatment defects and drive innovation in automotive manufacturing.