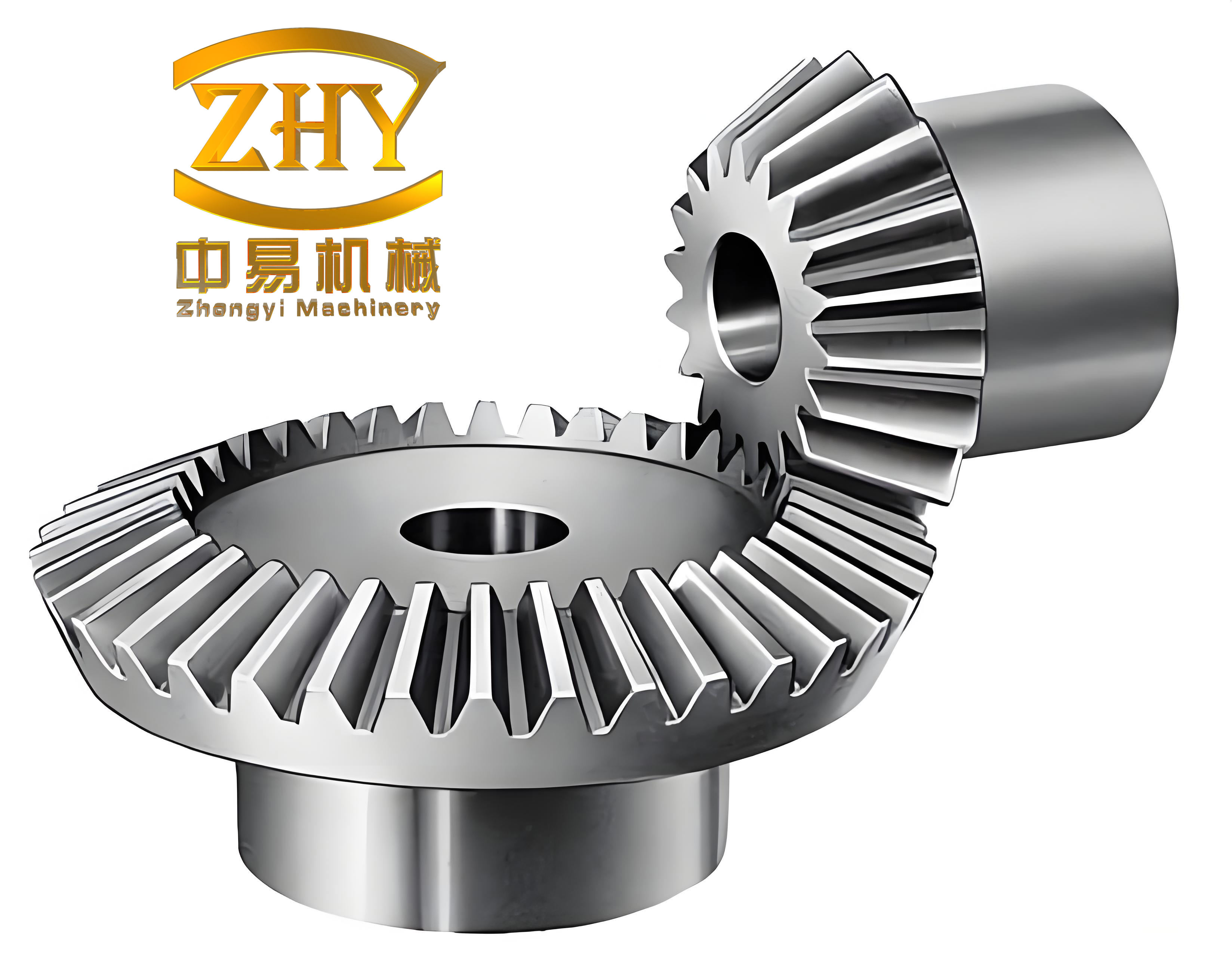

In the field of mechanical transmission, the straight bevel gear plays a crucial role due to its ability to transmit motion between intersecting shafts. One of the most critical aspects influencing the performance, durability, and noise characteristics of straight bevel gears is the contact zone between mating teeth. As an engineer specializing in gear technology, I have extensively studied the modification and control techniques for the contact zone of straight bevel gears, particularly in high-precision applications such as aerospace systems. This article delves into the factors affecting the contact zone, advanced modification methods, detection processes, and the impact of heat treatment, with a focus on achieving optimal performance through numerical and experimental approaches.

The contact zone of a straight bevel gear refers to the area where the tooth surfaces of the pinion and gear make contact during operation. Its size, shape, and position are vital for ensuring efficient power transmission, minimizing wear, and reducing noise. In many industrial standards, such as GB/T 11365-2019, the specification of contact patterns is left to agreement between suppliers and customers, without a direct link to gear accuracy grades. However, in high-stakes applications like aircraft high-lift systems, standards like ANSI/AGMA 2009-B01 provide detailed requirements for contact zone characteristics, including length, position, and boundary conditions. This highlights the importance of precise control in manufacturing straight bevel gears to meet stringent performance criteria.

Understanding the behavior of the straight bevel gear under load is essential for designing effective contact zones. Typically, the contact pattern changes with applied loads: under light loads, such as during rolling checks, the contact zone may be smaller and centered, whereas under working loads, it tends to shift toward the toe (large end) and expand. This phenomenon occurs due to deformations in the gearbox, shafts, and teeth. For instance, a well-designed straight bevel gear should have a contact zone that remains within safe boundaries, avoiding edges like the toe, heel, top, or root, even under full operational loads. Empirical data shows that the contact zone can increase by 5% to 35% in size and shift by 5% to 35% toward the toe as load increases. This relationship can be modeled using the following equation for contact zone displacement under load:

$$ \Delta C = k \cdot L $$

where \(\Delta C\) is the change in contact zone position, \(L\) is the applied load, and \(k\) is a constant dependent on gear geometry and material properties. For a straight bevel gear, ensuring that the contact zone is initially positioned toward the heel (small end) during light-load testing can compensate for this shift, as illustrated in the table below summarizing load effects:

| Load Condition | Contact Zone Size Change | Position Shift |

|---|---|---|

| Light Load (Rolling Check) | Minimal (5-10%) | Centered or slight heel bias |

| Working Load (Gearbox) | Significant (20-35%) | Toward toe (5-35%) |

Several factors influence the contact zone of a straight bevel gear, and as a practitioner, I have identified key elements that must be controlled during manufacturing. These include the machining process, gear blank accuracy, fixture design, tool parameters, and programming strategies. For example, in数控铣齿 (CNC milling) of straight bevel gears, the use of advanced methods like STRAIGHT BEVEL CONIFLEX allows for tooth flank modifications, such as crowning, which introduces a slight curvature along the tooth length to prevent edge contact. The crowning amount, often denoted as \(C_r\), is critical and can be calculated based on tool diameter and pressure angle. The formula for crowning in a straight bevel gear is:

$$ C_r = \frac{D_t \cdot \sin(\alpha)}{2} $$

where \(D_t\) is the tool diameter and \(\alpha\) is the pressure angle. A smaller tool diameter results in greater crowning, which affects the contact zone’s shape and size. The table below outlines the primary factors and their impacts on the straight bevel gear contact zone:

| Factor | Description | Impact on Contact Zone |

|---|---|---|

| Machining Process | e.g., CNC milling vs. traditional planing | CNC enables crowning and precise control; planing often produces linear contact without modification |

| Gear Blank | Accuracy of reference surfaces like bores and outer diameters | High precision reduces runout and ensures consistent tooth geometry |

| Fixture | Hydraulic fixtures vs. spring collets | Hydraulic fixtures offer better clamping (≤0.005 mm error), reducing positional errors |

| Tool Parameters | Blade pressure angle, edge radius, blade point | Pressure angle affects contact size; edge radius influences root fillet; blade point determines tooth slot width |

| Programming | Double roll method for finishing | Improves surface finish and accuracy by reducing cutting errors |

In my experience, tool parameters are particularly crucial for the straight bevel gear. The blade pressure angle directly influences the contact zone size: a larger angle results in a broader contact area. The edge radius, typically with a tolerance of ±0.127 mm, affects the root fillet and must be selected to meet minimum radius specifications. The blade point, or错刀距, should be slightly larger than half the tooth slot width at the heel to avoid undercutting or residual material. The maximum blade point \(W_{T.max}\) can be derived as:

$$ W_{T.max} = W_{L.i} – S_a $$

$$ W_{L.i} = A_o – F_w $$

$$ A_o = \frac{T_{on} – 2b_o \tan(\phi)}{2} – 0.0381 $$

where \(S_a\) is the stock allowance for double rolling, \(T_{on}\) is the mating gear’s toe arc thickness, \(b_o\) is the toe dedendum, \(A_o\) is the outer cone distance, and \(\phi\) is the pressure angle. This emphasizes the need for precise calculations in straight bevel gear manufacturing.

Modification techniques for the contact zone of straight bevel gears are essential to achieve desired performance. I have applied both first-order and second-order corrections to adjust the contact pattern. First-order corrections address issues like “top-root contact” or “toe-heel contact” by modifying pressure angle and spiral angle errors. For instance, a positive pressure angle correction shifts the contact zone toward the top land, while a negative correction moves it toward the root. Similarly, spiral angle corrections control the longitudinal position: a positive value shifts the contact toward the heel, and a negative value toward the toe. The amount of correction, \(\Delta \alpha\) for pressure angle and \(\Delta \beta\) for spiral angle, can be optimized using tooth contact analysis (TCA) software. The general equations for these corrections are:

$$ \Delta C_h = f(\Delta \alpha) \quad \text{for height direction} $$

$$ \Delta C_l = g(\Delta \beta) \quad \text{for length direction} $$

where \(f\) and \(g\) are functions derived from gear geometry. Second-order corrections, on the other hand, adjust the contact zone width without altering pressure or spiral angles. This involves combinations of first-order parameters to change the curvature mismatch, with positive values narrowing the contact and negative values widening it. In practice, I have used iterative testing and TCA simulations to refine these corrections for straight bevel gears, ensuring that the contact zone meets specifications such as 55-65% length and 65% position from the toe under light loads. The table below summarizes the correction methods:

| Correction Type | Purpose | Parameters Adjusted | Effect on Straight Bevel Gear Contact Zone |

|---|---|---|---|

| First-Order | Correct top-root or toe-heel misalignment | Pressure angle (\(\alpha\)), Spiral angle (\(\beta\)) | Shifts contact in height or length direction; e.g., +\(\Delta \beta\) moves contact to heel |

| Second-Order | Adjust contact width | Combination of \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) | Narrows or widens contact; improves mismatch control |

Detection and validation of the contact zone in straight bevel gears involve a multi-step process that I have implemented in production environments. First, coordinate measuring machine (CMM) inspections are performed to evaluate the tooth flank geometry against theoretical models. Using grid point analysis, such as a 5×9 point grid, deviations are kept within ±0.01 mm to ensure accuracy. The tooth flank error \(E_f\) for a straight bevel gear can be expressed as:

$$ E_f = \sqrt{ \sum_{i=1}^{n} (z_{actual,i} – z_{theoretical,i})^2 } $$

where \(z\) represents the surface coordinates. Next, rolling checks on dedicated testers assess the actual contact pattern and backlash under light loads. This step verifies that the straight bevel gear pair exhibits the specified contact characteristics, such as a centered pattern with no edge contact. Finally, the use of master gears ensures interchangeability and consistency. A master gear set, including a gold standard and inspection sets, serves as a reference for subsequent production. For example, in aerospace applications, straight bevel gears must achieve accuracy grades like ANSI/AGMA B5, and the master gear’s contact zone is used as a benchmark. The detection process highlights the importance of standardized procedures for straight bevel gear quality control.

Heat treatment is an inevitable step in straight bevel gear manufacturing, but it introduces distortions that can alter the contact zone. As I have observed, stresses from quenching and tempering cause dimensional changes, leading to shifts in tooth geometry. Typically, the contact zone may become smaller and less uniform after heat treatment, necessitating pre-heat treatment adjustments. For instance, by positioning the contact zone slightly toward the heel and ensuring adequate crowning, post-treatment deviations can be mitigated. The change in contact zone due to heat treatment, \(\Delta C_{ht}\), can be modeled empirically:

$$ \Delta C_{ht} = \delta \cdot C_{initial} $$

where \(\delta\) is a distortion factor based on material and process parameters. For high-strength steels like 300M, common in straight bevel gears, controlling quenching rates and using fixtures during heat treatment can reduce \(\delta\) to minimal levels. This proactive approach ensures that the straight bevel gear maintains acceptable contact patterns after treatment, as confirmed through post-heat treatment rolling checks.

In conclusion, the modification and control of the contact zone in straight bevel gears are pivotal for achieving high performance in demanding applications. Through advanced CNC milling techniques, precise tool management, and systematic corrections, it is possible to optimize the contact zone for any load condition. The integration of rigorous detection methods and master gear systems further enhances reliability and interchangeability. As straight bevel gear technology evolves, these practices will continue to drive improvements in efficiency and durability, solidifying their role in modern mechanical transmissions. The ongoing research and application of these principles demonstrate the critical importance of contact zone management in the straight bevel gear industry.

Reflecting on my experiences, I have found that a holistic approach—combining theoretical analysis with practical iterations—yields the best results for straight bevel gears. Future advancements may include real-time monitoring during machining and enhanced simulation tools, but the fundamentals of contact zone control will remain essential. By adhering to standards like ANSI/AGMA and leveraging technologies such as TCA, manufacturers can produce straight bevel gears that meet the highest criteria for aerospace and other precision fields.