Introduction

Quenching is a critical process in enhancing the mechanical properties of metal components. Traditional quenching methods rely heavily on empirical knowledge, leading to high time and economic costs. The integration of computational techniques with quenching processes has revolutionized this field by enabling the “visualization” of cooling dynamics through numerical simulation. This approach allows precise control over phase transformations, stress evolution, and distortion, thereby optimizing product quality.

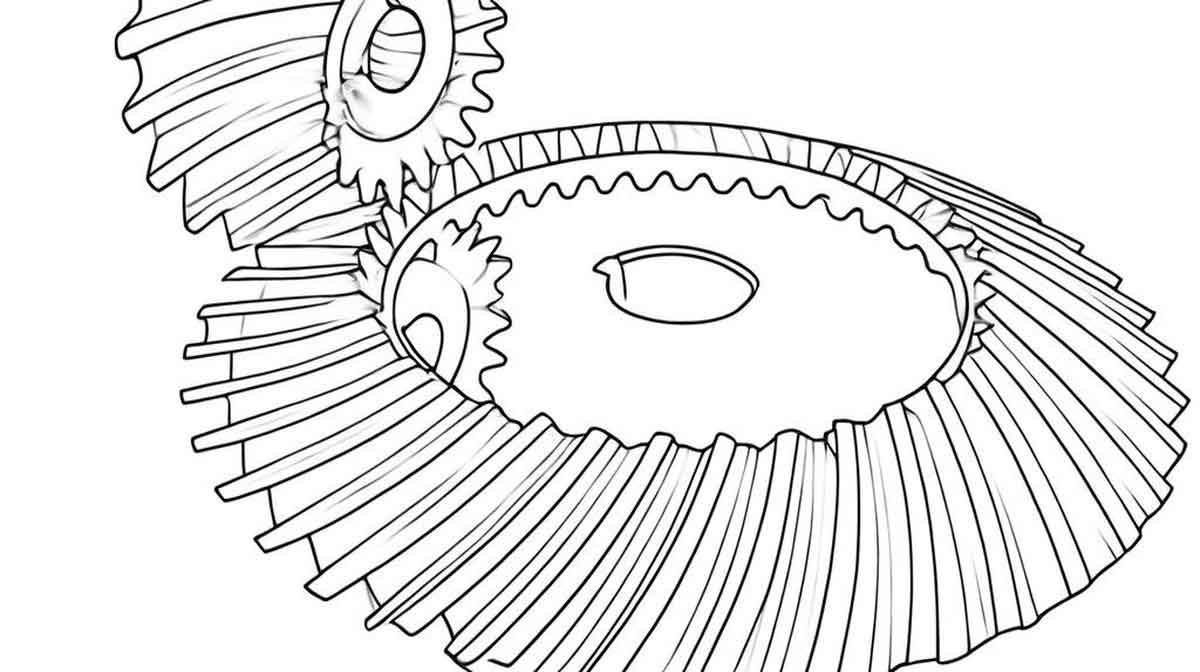

Spiral bevel gears, widely used in power transmission systems, require precise heat treatment to ensure durability and performance. However, their complex geometry poses challenges in achieving uniform cooling during quenching. Conventional simulations often use fixed heat transfer coefficients, which neglect the dynamic effects of quenching medium flow. This limitation underscores the need for advanced thermo-fluid-solid coupling models to capture the interplay between fluid dynamics, heat transfer, and structural responses.

This study presents a thermo-fluid-solid coupling method to simulate the quenching process of 45 steel spiral bevel gears. By replacing fixed heat transfer coefficients with coupled fluid-structure interactions, the model achieves higher accuracy in predicting temperature distributions, hardness, and residual stresses. Experiments validate the method, and parametric analyses identify optimal quenching conditions.

Methodology

1. Thermo-Fluid-Solid Coupling Framework

The coupling model integrates fluid dynamics, heat transfer, and solid mechanics to simulate quenching. Key equations governing the interactions are summarized below.

1.1 Fluid-Solid Interface Heat Transfer

The wall function method bridges fluid and solid domains. Dimensionless distance yp+yp+ and temperature Tp+Tp+ are defined as:yp+=ρCμ1/4kp1/2ypμ,Tp+=(Tp−Tw)(Cμ1/4kp1/2)(qw/ρCp),yp+=μρCμ1/4kp1/2yp,Tp+=(qw/ρCp)(Tp−Tw)(Cμ1/4kp1/2),

where ρρ, CpCp, μμ, kpkp, and TwTw denote density, specific heat, viscosity, turbulent kinetic energy, and wall temperature, respectively. The equivalent thermal conductivity λ1λ1 and heat flux qwqw are derived as:λ1=yp+ηpμCp,qw=yp+(Tp−Tw)ypμCp.λ1=ηpyp+μCp,qw=ypyp+(Tp−Tw)μCp.

1.2 Fluid Flow and Boiling Heat Transfer

The Eulerian multiphase model accounts for boiling phenomena. Mass, momentum, and energy equations for liquid (ll) and vapor (gg) phases are:∂∂t(αiρi)+∇(αiρiui)=∑j(m˙ji−m˙ij),∂t∂(αiρi)+∇(αiρiui)=j∑(m˙ji−m˙ij),∂∂t(αiρiui)+∇(αiρiuiui)=∇τi−αi∇p+αiρig+Fi,∂t∂(αiρiui)+∇(αiρiuiui)=∇τi−αi∇p+αiρig+Fi,∂∂t(αiρihi)+∇(αiρiuihi)=−αi∂p∂t+τi:∇ui+∇qi+Si.∂t∂(αiρihi)+∇(αiρiuihi)=−αi∂t∂p+τi:∇ui+∇qi+Si.

The RPI wall boiling model partitions heat flux into three components:qw=qconv+qevap+qquen=λAconv(Tw−Tl)+π6fNdw3ρghlg+2Aquenλρlcplπτw(Tw−Tl).qw=qconv+qevap+qquen=λAconv(Tw−Tl)+6πfNdw3ρghlg+2Aquenπτwλρlcpl(Tw−Tl).

1.3 Solid Phase Transformation and Stress Analysis

The temperature-stress-microstructure coupling model incorporates:

- Heat conduction:

∇(λ∇T)+Q=∂(ρCpT)∂t,Q=∑ΔHidfidt.∇(λ∇T)+Q=∂t∂(ρCpT),Q=∑ΔHidtdfi.

- Phase transformation:

- Diffusional transformations (JMA equation):

- Martensitic transformation (K-M equation):

- Stress-strain relationship:

dϵ=dϵe+dϵp+dϵth+dϵtr+dϵtp.dϵ=dϵe+dϵp+dϵth+dϵtr+dϵtp.

Experimental Setup

The spiral bevel gear, made of 45 steel, had the parameters listed in Table 1. Five feature points (A–E) were monitored using K-type thermocouples during quenching in 20°C water. Simulations were performed under static and flowing N32 oil (60°C) conditions.

Table 1: Parameters of the spiral bevel gear

| Parameter | Value | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of teeth | 20 | Addendum height | 4 mm |

| Module | 4 mm | Dedendum height | 5 mm |

| Face width | 23 mm | Pressure angle | 20° |

| Helix direction | Right-hand | Spiral angle | 35° |

| Step diameter | Φ65 mm | Bore diameter | Φ18 mm |

Results and Discussion

1. Validation Against Experiments

Figure 1 compares simulated and experimental cooling curves for static quenching. The thermo-fluid-solid coupling model showed a maximum relative error of 9.2%, slightly higher than the 7.4% error of traditional methods. Discrepancies arose from uncertainties in boiling heat transfer modeling but remained within acceptable limits.

Key observations:

- Cooling rates decreased from tooth tip (A) to root (C) due to geometric thickness variations.

- Internal bore surfaces (D) exhibited slower cooling, with errors below 1.7% in traditional simulations.

2. Flow-Dependent Heat Transfer

For flowing N32 oil (2 m/s inlet velocity), velocity gradients near the spiral bevel gear significantly affected cooling (Figure 2). The tooth tip experienced minimal flow (0.108 m/s), while the bore region retained higher velocities.

Thermal distribution:

- Traditional simulations overestimated temperatures at the gear’s large and small ends due to uniform heat transfer coefficients.

- The coupling model captured localized cooling effects, yielding lower temperatures at high-flow regions (Table 2).

Table 2: Temperature differences between simulation methods

| Region | Traditional Simulation (°C) | Coupling Model (°C) |

|---|---|---|

| Large end | 320 | 298 |

| Small end | 315 | 290 |

| Tooth root | 285 | 280 |

3. Hardness and Residual Stress Analysis

Table 3 summarizes hardness and stress values at six feature points under varying flow rates. Hardness increased with flow velocity, peaking at 52.0 HRC (2 m/s). Residual stresses were predominantly compressive, favoring fatigue resistance.

Table 3: Hardness and residual stresses at different flow rates

| Point | Hardness (HRC) | Residual Stress (MPa) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 m/s | 1 m/s | 1.5 m/s | 2 m/s | 0.5 m/s | 1 m/s | 1.5 m/s | 2 m/s | |

| 1 | 21.7 | 20.9 | 22.6 | 25.3 | -33.31 | -33.75 | -33.75 | -34.09 |

| 2 | 27.4 | 28.4 | 28.8 | 30.3 | 5.75 | 6.57 | 6.68 | 6.78 |

| 3 | 33.5 | 34.5 | 35.1 | 35.7 | -2.18 | -2.28 | -2.50 | -2.61 |

| 4 | 39.1 | 40.3 | 40.7 | 41.5 | -6.39 | -6.96 | -7.19 | -7.77 |

| 5 | 40.8 | 42.4 | 42.9 | 43.3 | -14.44 | -14.60 | -14.66 | -14.79 |

| 6 | 47.5 | 47.5 | 47.7 | 47.9 | -34.89 | -38.49 | -38.77 | -39.68 |

Mechanisms:

- Higher flow rates enhanced heat extraction, promoting martensite formation and hardness.

- Compressive stresses arose from phase transformation strains, peaking at -81.56 MPa (2 m/s).

Conclusions

- Accuracy and Convenience: The thermo-fluid-solid coupling model achieved reasonable accuracy (9.2% error) and streamlined simulations by eliminating manual heat transfer coefficient zoning.

- Flow Effects: Increasing quenching oil velocity improved hardness (52.0 HRC at 2 m/s) while maintaining favorable compressive stresses.

- Optimal Parameters: A flow rate of 2 m/s is recommended for balancing hardness, stress, and distortion in spiral bevel gear quenching.

This study underscores the potential of coupled numerical models in advancing heat treatment optimization for complex components like spiral bevel gears. Future work will focus on refining boiling submodels and extending the framework to multi-material systems.