In the realm of offshore operations, self-elevating platforms play a pivotal role in various applications such as oil drilling, accommodation, and wind turbine installation. These platforms rely on a robust lifting system, where the spud legs and their guiding mechanisms are critical for stability and functionality. The guiding devices, positioned within the lifting foundation, ensure the smooth vertical movement of the spud legs during elevation and lowering processes. However, frequent operations often lead to wear, damage, or even detachment of these components, emphasizing the need for optimized design. This article delves into the design aspects of guiding devices for truss-framed rack and pinion type spud legs, drawing from theoretical analysis and practical case studies of three representative platform types. By examining factors such as arrangement, limiting methods, clearance between wear plates and rack teeth, and fixation techniques, I aim to present a comprehensive comparison and derive an optimal design approach. The focus is on enhancing durability, reducing maintenance costs, and ensuring operational continuity, with repeated emphasis on the rack and pinion gear system as the core of the lifting mechanism.

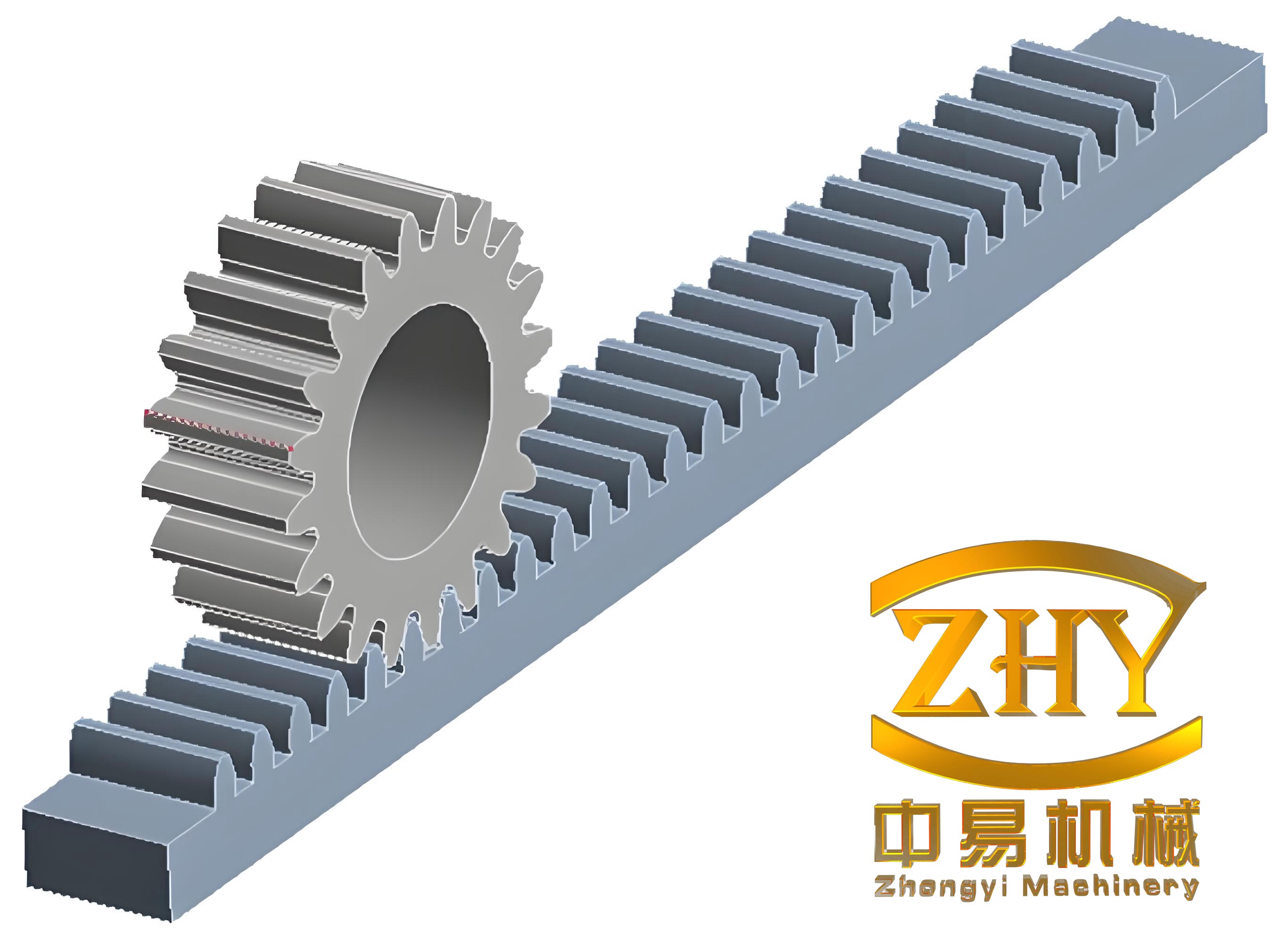

The rack and pinion gear system is fundamental to the operation of self-elevating platforms, particularly in deep-water environments where truss-framed spud legs are preferred due to their reduced wave loads and lighter weight compared to cylindrical legs. In this system, the rack, integrated into the spud leg’s chord members, engages with pinions driven by electric motors to facilitate precise vertical movement. The guiding devices act as supports that prevent lateral displacement, rotation, and excessive vibration during these operations. Over time, the wear plates within these devices undergo significant stress from friction and compression, necessitating materials like copper-aluminum alloys or high-strength steels for longevity. A well-designed guiding system not only mitigates wear but also aligns with the precision required for the rack and pinion mechanism, ensuring that the gears mesh correctly without misalignment. This article explores how different design choices impact performance, using analytical models and empirical data to highlight best practices. Through this investigation, I seek to provide insights that can inform future designs, leveraging the efficiency of the rack and pinion gear for enhanced platform reliability.

To understand the current state of truss-framed rack and pinion type spud legs, it is essential to recognize their structural composition. Each leg typically consists of chord members—which include a rack plate and semi-circular pipes—along with horizontal, diagonal, and rhombic tubular braces. The rack and pinion system enables controlled elevation, but the guiding devices are what maintain alignment. These devices are welded or bolted to the lifting foundation and incorporate wear plates that interface with the rack teeth. The choice of material and design parameters, such as clearance, directly influences wear rates. For instance, excessive clearance can lead to leg wobbling and uneven loading, while insufficient clearance may cause binding and accelerated wear. In deep-water applications, where platforms like jack-up rigs operate, the rack and pinion gear must handle dynamic loads, making the guiding system a linchpin for safety. Current industry practices vary, with some designs opting for multi-side limiting methods and others focusing solely on tooth tip engagement. Through comparative analysis, I will evaluate these approaches, emphasizing how the rack and pinion interaction can be optimized through thoughtful guiding device design.

In the following sections, I compare three distinct self-elevating platform types—referred to as A, B, and C—each representing a different design philosophy for guiding devices. Platform A employs a three-sided limiting approach with guides at upper, middle, and lower positions, while Platforms B and C use tooth tip limiting with variations in arrangement and fixation. The clearance between wear plates and rack teeth ranges from 3 mm to 40 mm, affecting stability and wear. Additionally, fixation methods range from welded to bolted configurations, impacting maintainability. To quantify these differences, I will incorporate tables and mathematical formulations. For example, the allowable deformation in rack pitch can be modeled using equations that account for manufacturing tolerances and operational stresses. Consider the formula for maximum rack crown deformation: $$ \delta_{\text{max}} = \frac{L \cdot \theta}{2} $$ where \( \delta_{\text{max}} \) is the maximum deformation, \( L \) is the span length, and \( \theta \) is the angular deviation per unit length. This relates directly to the clearance design, as excessive deformation may require larger gaps to avoid interference. Similarly, wear rates can be approximated using Archard’s wear equation: $$ V = K \frac{F_n \cdot s}{H} $$ where \( V \) is the wear volume, \( K \) is the wear coefficient, \( F_n \) is the normal force, \( s \) is the sliding distance, and \( H \) is the material hardness. By applying such models, I can assess the long-term implications of each design choice on the rack and pinion system’s performance.

| Design Aspect | Platform A | Platform B | Platform C |

|---|---|---|---|

| Limiting Method | Three-sided (teeth and sides) | Tooth tip only | Tooth tip only |

| Guide Positions | Upper, Middle, Lower | Upper and Lower | Upper, Middle, Lower with additional permanent guides |

| Wear Plate to Tooth Tip Clearance (mm) | Upper: 10, Middle: 40, Lower: 40 | Upper: 4, Lower: 4 | Upper: 3, Middle: 3, Lower: 5 (with bell-mouth design) |

| Fixation Method | Bolted with welded pads | Bolted with welded limits | Bolted with removable limit blocks |

| Material | 50 Ksi steel with copper-aluminum | HARDBOX 500 | HARDOX 400 with EH36 steel |

| Maintenance Accessibility | Difficult (requires cutting welds) | Moderate (requires leg adjustment) | Easy (direct bolt removal) |

Platform A’s guiding device design features a comprehensive three-sided limit, which aims to restrain the rack plate from all directions. However, this approach introduces complexity in fabrication and alignment. The rack and pinion gear in this system must contend with potential misalignments due to the tight constraints, leading to increased friction forces. The clearance values—10 mm at the upper guide and 40 mm at the middle and lower guides—are relatively large, which can permit significant leg sway under load. From a theoretical perspective, the resultant lateral force on the wear plates can be expressed as: $$ F_l = \mu \cdot F_n + \frac{m \cdot v^2}{r} $$ where \( F_l \) is the lateral force, \( \mu \) is the friction coefficient, \( F_n \) is the normal force from the rack and pinion engagement, \( m \) is the effective mass, \( v \) is the velocity of leg movement, and \( r \) is the radius of curvature due to deformation. In practice, Platform A has reported issues with wear plate cracking and detachment, underscoring the drawbacks of oversized clearances and multi-sided limiting. The rack and pinion mechanism here may experience uneven loading, accelerating wear on both the gears and guides.

In contrast, Platform B adopts a simplified tooth tip limiting method, which reduces the number of contact points and focuses on critical areas. The clearance is consistently set at 4 mm, promoting better alignment but requiring higher manufacturing precision. The fixation involves bolts with welded peripheries, which complicates replacement procedures. For instance, removing wear plates necessitates adjusting the leg position to access bolts hidden by the rack teeth, which can be time-consuming. The rack and pinion gear in this design benefits from the reduced clearance, as it minimizes play and enhances meshing accuracy. However, the wear plate material—HARDBOX 500—offers high abrasion resistance, but the fixation method may lead to stress concentrations. Analytically, the stress on the bolts can be modeled as: $$ \sigma_b = \frac{F_t}{A_b} $$ where \( \sigma_b \) is the bolt stress, \( F_t \) is the tensile force from operational loads, and \( A_b \) is the cross-sectional area of the bolt. If the welding fails or bolts loosen, the entire guiding system could compromise the rack and pinion interaction, leading to potential failures.

Platform C represents an optimized approach, with tooth tip limiting and a strategic arrangement of guides at upper, middle, and lower positions, supplemented by permanent welded guides in intermediate areas. The clearances are tight—3 mm at upper and middle guides and 5 mm at the lower guide with a bell-mouth entry—striking a balance between stability and allowance for deformations. The bell-mouth design, featuring a gradual curvature at the leg entry point, facilitates smooth engagement with the rack and pinion system without increasing overall clearance. The fixation method employs removable limit blocks and bolts positioned away from the rack teeth, enabling easy maintenance without leg adjustment. This design considers the rack crown deformation, which for a typical rack and pinion system can be calculated as: $$ \delta_c = \frac{p \cdot n}{2} \cdot \epsilon $$ where \( \delta_c \) is the crown deformation, \( p \) is the rack pitch (e.g., 304.8 mm), \( n \) is the number of teeth over the span, and \( \epsilon \) is the permissible deviation per tooth (e.g., ≤2 mm per 28 teeth). For Platform C, the 3–5 mm clearance range accommodates this deformation while minimizing excessive movement. The use of HARDOX 400 and EH36 steels ensures durability, and the distributed guide positions分担 loads effectively, reducing peak stresses on any single component.

To derive an optimal design, I synthesize the findings from the three platforms. The tooth tip limiting method is superior, as it directly protects the rack and pinion gear from misalignment without over-constraining the system. This approach leverages the triangular truss geometry, where each chord member naturally limits the others, reducing the need for complex multi-sided guides. For guide arrangement, positions at the top of the lifting foundation, the bottom near the hull, and intermediate points are essential to handle high-stress zones during leg entry and gear engagement. The clearance between wear plates and rack teeth should be minimized to 3–5 mm, as this range counters typical deformations without causing excessive friction. Mathematically, the optimal clearance \( C_{\text{opt}} \) can be related to the rack deformation and operational tolerance: $$ C_{\text{opt}} = \delta_{\text{max}} + T_{\text{assembly}} $$ where \( T_{\text{assembly}} \) is the assembly tolerance, typically 1–2 mm. For instance, with \( \delta_{\text{max}} \) around 4 mm, a 3–5 mm clearance ensures smooth operation. The bell-mouth design at the lower guide is highly recommended for easier leg insertion, using a curved profile that gradually reduces offset, such as: $$ y(x) = y_0 \cdot \left(1 – \frac{x}{L}\right)^2 $$ where \( y(x) \) is the offset at height \( x \), \( y_0 \) is the initial offset (e.g., 12 mm), and \( L \) is the bell-mouth height (e.g., 1 m). This minimizes initial impact forces on the rack and pinion gear.

| Parameter | Optimal Value or Method | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Limiting Method | Tooth tip only | Reduces complexity, leverages truss geometry, and protects rack and pinion gear |

| Guide Positions | Upper, Intermediate, Lower with bell-mouth | Manages high-stress points and facilitates leg entry |

| Clearance (mm) | 3–5 | Balances deformation allowance and stability for rack and pinion engagement |

| Fixation | Bolted with removable limit blocks | Enhances maintainability and reduces downtime |

| Material | High-strength steel (e.g., HARDOX 400) with backup plates | Improves wear resistance and load distribution |

| Maintenance | Direct bolt access without leg adjustment | Lowers operational costs and improves safety |

Regarding fixation, the bolted method with removable limit blocks, as seen in Platform C, is ideal for ease of replacement and reliability. This design allows for quick disassembly by simply unbolting components, unlike welded methods that require cutting and rewelding. The rack and pinion system benefits from this, as maintenance can be performed without extensive platform downtime. Furthermore, the use of high-strength materials in wear plates, combined with intermediate permanent guides, extends service life by distributing loads. For example, the contact pressure on wear plates can be estimated using: $$ P_c = \frac{F_n}{A_c} $$ where \( P_c \) is the contact pressure and \( A_c \) is the contact area. By optimizing the guide spacing and material properties, this pressure can be kept within safe limits, reducing wear rates. In practice, this approach has proven effective in Platforms B and C, which report fewer instances of damage compared to Platform A.

In conclusion, the design of guiding devices for truss-framed rack and pinion type spud legs is a critical factor in the operational efficiency and longevity of self-elevating platforms. Through comparative analysis, I have demonstrated that a tooth tip limiting method with 3–5 mm clearance, strategic guide placement, and bolted fixation offers the best balance of stability, maintainability, and durability. The rack and pinion gear system, central to these platforms, relies on precise alignment and minimal play to function effectively, and the optimal guiding design supports this by mitigating wear and misalignment risks. By adopting these recommendations, designers can reduce maintenance frequency, lower costs, and enhance operational continuity, ultimately contributing to safer and more reliable offshore operations. Future work could explore advanced materials or real-time monitoring systems to further optimize the rack and pinion interaction, but the principles outlined here provide a solid foundation for current practices.

The integration of mathematical models and empirical data underscores the importance of a systematic approach to guiding device design. For instance, the deformation and wear equations highlighted earlier can be used in predictive maintenance schedules, allowing operators to anticipate replacement needs based on operational parameters. Additionally, the rack and pinion mechanism’s efficiency can be quantified using mechanical advantage formulas, such as: $$ \eta = \frac{\text{Output work}}{\text{Input work}} = \frac{F_{\text{lift}} \cdot d_{\text{leg}}}{T_{\text{motor}} \cdot \omega} $$ where \( \eta \) is the efficiency, \( F_{\text{lift}} \) is the lifting force, \( d_{\text{leg}} \) is the leg displacement, \( T_{\text{motor}} \) is the motor torque, and \( \omega \) is the angular velocity. By ensuring that guiding devices minimize frictional losses and misalignment, this efficiency can be maximized, reinforcing the value of the optimal design. In summary, the rack and pinion gear system is not just a component but the heart of self-elevating platforms, and its performance is inextricably linked to the guiding devices that support it. Through continuous improvement and adherence to best practices, the industry can achieve higher standards of safety and productivity.