In my extensive experience as a mechanical engineer specializing in transmission components, I have frequently encountered the challenges associated with manufacturing rear output gear shafts for pickup truck transmissions. These gear shafts are critical for transmitting torque to the differential, and their design often features a large stepped configuration with a composite blind hole at the larger end. The traditional manufacturing routes for such gear shafts have predominantly relied on cross wedge rolling or horizontal forging processes. However, these methods present significant limitations, particularly the inability to forge the composite blind hole directly, leading to increased material waste and additional machining time. This article details my comprehensive approach to optimizing both the forging and rough machining processes for these gear shafts by implementing vertical forging technology. This method not only allows for the direct forging of the blind hole but also streamlines subsequent machining operations, resulting in enhanced material utilization, improved mechanical properties, and reduced production costs. Throughout this discussion, I will emphasize the technical considerations and calculations involved, making frequent reference to gear shafts as a central component in automotive drivetrains.

The conventional manufacturing of gear shafts, especially for high-demand applications, often involves processes like cross wedge rolling. This technique is efficient for producing stepped shafts but imposes constraints such as a reduction in cross-sectional area typically limited to less than 75%. Furthermore, the flow lines generated in cross wedge rolling are not always optimal, which can adversely affect the performance of subsequent thread rolling operations on the gear shafts. Horizontal forging, while offering better control over grain flow, suffers from high material consumption and difficulties in preform preparation. Most critically, neither method can forge the composite blind hole found in many rear output gear shafts. This necessitates that the hole be machined entirely from solid stock, which is both time-consuming and wasteful. To address these issues, I developed and implemented a vertical forging process specifically tailored for these gear shafts. The fundamental advantage of vertical forging lies in its ability to perform localized forging operations along the axis of the workpiece, making it ideal for creating complex features like blind holes while maintaining excellent material flow characteristics.

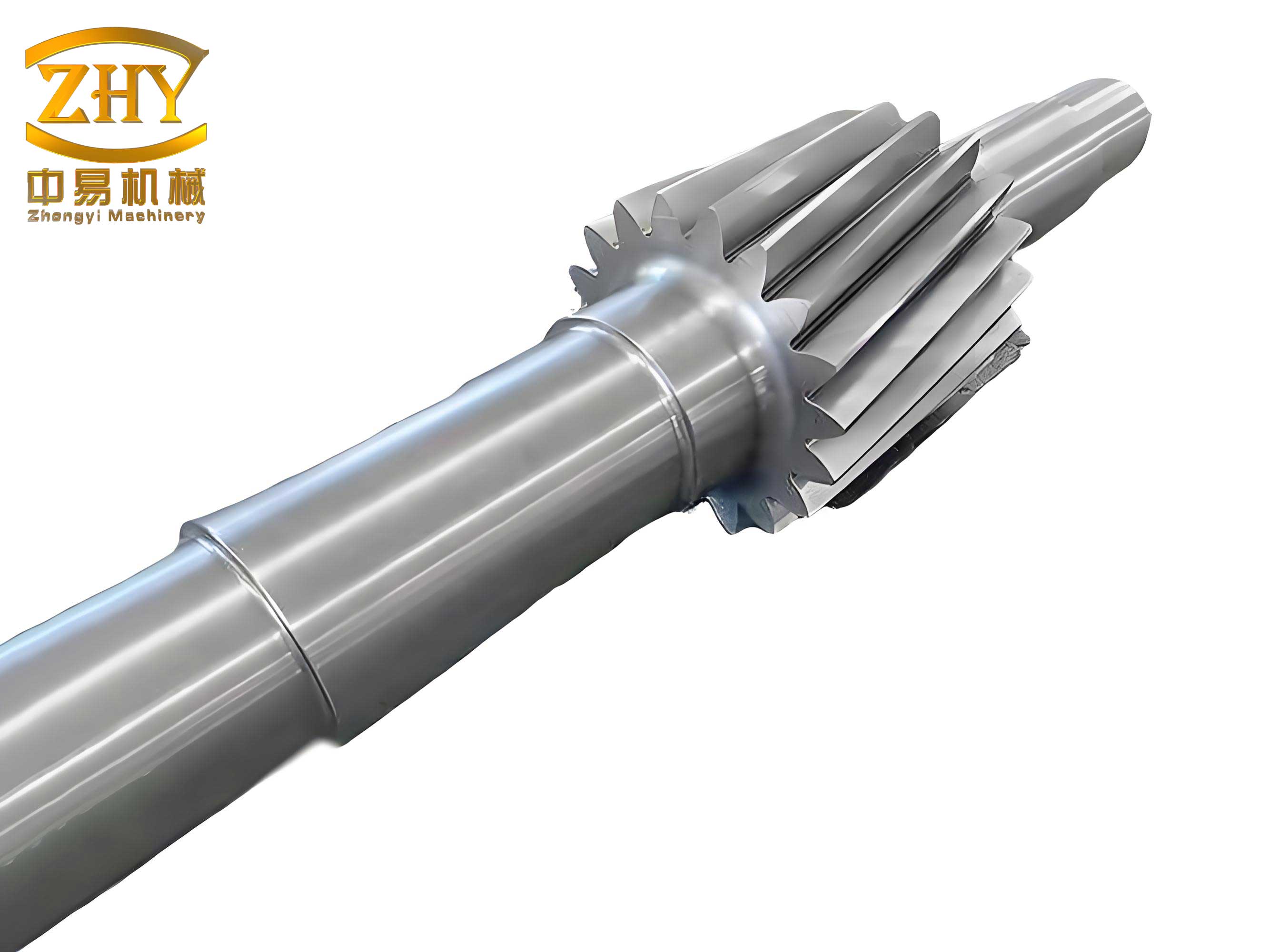

The design of the forging process begins with a detailed analysis of the final gear shaft component. The shaft has a major diameter of 134 mm at the large end, a thickness of 42.4 mm, and a long, slender shank. The composite blind hole has a depth of 34 mm. To forge this geometry, a multi-step process is required. First, the raw material, typically a round bar, is cut to size. For this specific gear shaft, the initial billet dimensions are 80 mm in diameter and 192.5 mm in length. The weight of the final forged gear shaft is approximately 7.2 kg. The material utilization can be calculated by comparing the volume of the final forged part to the volume of the initial billet. The volume of a cylinder is given by $V = \pi r^2 h$. If we denote the billet volume as $V_b$ and the forged gear shaft volume as $V_f$, the material utilization $\eta$ is:

$$\eta = \frac{V_f}{V_b} \times 100\%$$

For our case, the billet volume is:

$$V_b = \pi \times (40 \text{ mm})^2 \times 192.5 \text{ mm} \approx 967,605 \text{ mm}^3$$

The forged volume is more complex to calculate precisely due to the stepped shape and blind hole, but an estimate based on the 7.2 kg weight and material density (around 7.85 g/cm³ for steel) gives $V_f \approx 917,000 \text{ mm}^3$. This yields a material utilization of roughly 94.8%, a significant improvement over methods that require drilling the blind hole from solid.

The forging sequence involves several key operations. After cutting, the billet is heated to a temperature of $1200 \pm 50^\circ \text{C}$ using a medium-frequency induction heater. The heated billet is then subjected to a preforming operation on an air hammer to draw out the shank section. This is essential because the slender shank cannot be formed directly in the final forging die without causing defects. The preform shape closely matches the final shank geometry, with a draft angle of $1.5^\circ$. The preformed workpiece is then transferred to a 1000-ton friction screw press for the final vertical forging operation. In this stage, the large end of the gear shaft is forged, and the composite blind hole is simultaneously formed. The forging die is designed to leave a machining allowance of 1.6 mm per side on the major diameters and critical surfaces. The parting line is located at the mid-diameter of the 134 mm section. After forging, the flash is trimmed off using a 315-ton trimming press. A critical aspect of this process is the control of forging parameters such as temperature, deformation speed, and lubrication to ensure proper metal flow and prevent defects like laps or cold shuts in the gear shafts.

The design of the forging die is paramount to the success of the vertical forging process for gear shafts. Given the long, slender shank of the gear shaft, a monolithic lower die would be extremely difficult to machine due to the deep cavity required. Therefore, I opted for a split-die construction. The die assembly consists of four main components: the upper die, the lower die insert, the lower die holder, and the ejector pin. The materials and hardness values are selected based on the severe thermal and mechanical stresses encountered during forging. The upper die and lower die holder are made from 5CrNiMo steel, a common hot-work die steel. The lower die insert, which forms the intricate features of the gear shaft including the blind hole, is made from H13 steel, which offers superior thermal fatigue resistance. The ejector pin, which must withstand high pressure and wear during part ejection, is made from 3Cr2W8V steel. The hardness values are carefully chosen to balance wear resistance and toughness. The following table summarizes the die components and their specifications:

| Component | Material | Hardness (HRC) | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Upper Die | 5CrNiMo | 42-46 | Forms the top impression and applies forging force. |

| Lower Die Insert | H13 | 42-46 | Forms the detailed geometry and blind hole of the gear shaft. |

| Lower Die Holder | 5CrNiMo | 40-44 | Supports the insert and provides structural integrity. |

| Ejector Pin | 3Cr2W8V | 44-48 | Ejects the forged gear shaft from the die cavity. |

To minimize die shift during forging, locking keys are incorporated between the upper die and the lower die insert. The fit between the lower die holder and the insert is a clearance fit, with a gap of 0.1 to 0.2 mm. A larger gap would allow material to flash into the interface, hindering ejection. The clearance between the ejector pin and the die is maintained at 0.8 to 1.2 mm. Die refurbishment is achieved by sinking the die surfaces, extending the service life of these expensive tooling components. The successful production of high-quality forged gear shafts relies heavily on this robust die design.

After forging, the gear shafts undergo isothermal normalizing to achieve a uniform and machinable microstructure, followed by shot blasting to remove scale. The subsequent rough machining process must be re-engineered to accommodate the new forged geometry, which now includes a pre-formed blind hole. In the traditional process for gear shafts made by cross wedge rolling, the initial step involves milling both end faces and drilling center holes. The shaft is then machined between centers, using a drive plate on the large end, to rough turn the outer diameters and faces. The blind hole is subsequently drilled and bored. This method requires a semi-finishing turn to achieve the tight geometric tolerances on the shank, such as the runout of the $\phi 41.7_{-0.2}^{0}$ mm diameter relative to the centerline.

With the vertically forged gear shafts, the presence of the blind hole at the large end prevents the drilling of a center hole on that side. Therefore, a new two-operation machining strategy was developed. The first operation focuses on machining the large end and the blind hole to establish a precise datum for the second operation. This is performed on a CNC lathe. The steps are as follows: 1) Chuck the forged gear shaft by the shank (which is still rough). 2) Face the large end to establish a clean reference surface. 3) Turn the major outer diameters and faces to their rough dimensions. A critical dimension is the $15.6 \pm 0.1$ mm step, which must be held to a tighter tolerance of $\pm 0.05$ mm to ensure accurate positioning later. 4) Bore the $\phi 60_{-0.2}^{0}$ mm hole to a depth of $34.2_{+0.2}^{-0.1}$ mm. 5) Finally, drill the $\phi 40_{-0.3}^{0}$ mm through-hole. It is crucial to bore the larger hole before drilling the smaller one to prevent drill wander caused by any misalignment between the forged surfaces.

The second operation completes the machining of the shank and the opposite end. The workpiece is now chucked using soft jaws on the freshly machined $\phi 134_{-0.2}^{0}$ mm diameter of the large end. The sequence is: 1) Face the free end of the shank to achieve the total length of $271.4 \pm 0.15$ mm. 2) Drill a center hole (e.g., R5) at this end. 3) Retract the tool, and use a hydraulically actuated tailstock center to support the free end. This provides a rigid “between centers” setup for turning the long shank. 4) Rough and finish turn the shank diameters, including the critical $\phi 41.7_{-0.2}^{0}$ mm section. The datum for measuring runout is now the axis established by the machined $\phi 134$ mm diameter (designated as datum A). The machining allowance for the large diameter is split between operations: in the first op, it is turned to $\phi 134_{-0.1}^{0}$ mm, and in the second op, it is finished to $\phi 134_{-0.2}^{-0.1}$ mm. This prevents a visible witness line from forming. The clamping force and cutting parameters must be optimized to avoid distortion of the slender gear shafts during machining. The table below contrasts the key steps of the old and new rough machining processes for these gear shafts.

| Process Stage | Traditional Process (Cross Wedge Rolled) | Optimized Process (Vertically Forged) |

|---|---|---|

| Setup Reference | Two center holes (drilled on both ends). | Chucked on machined large end diameter, tailstock center on shank end. |

| First Major Operation | Turn all outer diameters between centers. | Machine large end diameters and bore/blind hole. |

| Hole Making | Drill and bore blind hole from solid. | Finish bore and drill pre-forged hole. |

| Critical Tolerance Achievement | Requires semi-finish turning for shank runout. | Shank runout achieved directly in second op due to rigid setup. |

| Estimated Machining Time | Higher due to extra drilling and semi-finish pass. | Lower due to reduced stock removal and fewer operations. |

The benefits of this optimized process for manufacturing gear shafts are substantial and multifaceted. Firstly, the vertical forging process itself offers a marked improvement in material yield. By forging the blind hole, we eliminate the need to remove a significant volume of material via drilling. The material savings can be calculated more formally. Let $V_{hole}$ be the volume of the removed material for the blind hole if drilled from solid. For a hole of diameter $D_h$ and depth $L_h$, $V_{hole} = \frac{\pi}{4} D_h^2 L_h$. For our $\phi 40$ mm hole that is 34 mm deep, $V_{hole} \approx 42,735 \text{ mm}^3$. This corresponds to a mass saving of about 0.33 kg per gear shaft (using density $\rho = 7.85 \times 10^{-6} \text{ kg/mm}^3$). Over a large production run, this translates to significant cost savings in raw material for these gear shafts.

Secondly, the metallurgical quality of the gear shafts is enhanced. The vertical forging process, involving axial deformation, promotes a more favorable grain flow along the contour of the part, especially around the critical fillets and the base of the blind hole. This improves fatigue resistance and strength, which are vital for dynamically loaded gear shafts in vehicle transmissions. The flow lines can be described by the deformation gradient tensor $F_{ij} = \frac{\partial x_i}{\partial X_j}$, where $x_i$ are the spatial coordinates after forging and $X_j$ are the material coordinates before forging. In an ideal forging process for gear shafts, we aim for $F_{ij}$ to align with the principal stress directions, minimizing shear components that can lead to weak interfaces.

Thirdly, the machining process is significantly streamlined. The reduction in the number of operations, particularly the elimination of a dedicated semi-finishing turn and the more efficient hole-making, reduces cycle time. Furthermore, the rigid setup in the second operation (chuck and live center) allows for higher feed rates without compromising accuracy. The relationship between machining parameters and surface finish or dimensional accuracy is complex, but generally, the metal removal rate $Q$ is given by $Q = v_c \times f \times a_p$, where $v_c$ is the cutting speed, $f$ is the feed rate, and $a_p$ is the depth of cut. With a more rigid setup, we can increase $f$ or $a_p$ while maintaining stability, directly increasing productivity for machining these gear shafts.

To further illustrate the economic impact, consider a simplified cost model. The total cost $C_{total}$ per gear shaft can be expressed as:

$$C_{total} = C_{material} + C_{forging} + C_{machining} + C_{tooling}$$

Where:

– $C_{material} = \rho V_{billet} \times P_{material}$

– $C_{forging}$ includes energy, labor, and press depreciation.

– $C_{machining} = T_{machining} \times R_{machine}$

– $C_{tooling}$ is the amortized die and tool cost.

The optimization reduces $V_{billet}$, $T_{machining}$, and potentially tool wear due to less aggressive drilling. Even if $C_{forging}$ for vertical forging is slightly higher than for cross wedge rolling, the savings in material and machining often result in a lower $C_{total}$. This makes the vertically forged gear shafts more competitive.

In conclusion, the transition from cross wedge rolling or horizontal forging to vertical forging for the production of rear output gear shafts represents a significant technological advancement. This optimization addresses the core limitations of previous methods by enabling the direct forging of complex blind holes, which is a common feature in many automotive gear shafts. The accompanying redesign of the rough machining sequence capitalizes on the new forged geometry, establishing more precise and stable datums to achieve stringent tolerances efficiently. The combined result is a manufacturing route that offers superior material utilization, enhanced mechanical properties through controlled grain flow, and reduced processing time. For engineers and manufacturers focused on producing high-performance, cost-effective transmission components like gear shafts, the vertical forging and optimized machining strategy detailed here provides a robust and validated framework. Future work could explore the integration of simulation software to further optimize die design and forging parameters for different geometries of gear shafts, or investigate the use of advanced coatings on machining tools to extend tool life when processing these forged components.