In my research on advanced mechanical transmission systems, I have focused extensively on the worm gear drive, a critical component in many industrial applications due to its ability to provide high reduction ratios and compact design. Specifically, I investigated a novel type known as the roller enveloping end face engagement worm gear drive, which promises enhanced performance through increased contact pairs and reduced friction. This worm gear drive utilizes rollers as the teeth of the worm wheel, enveloped by a conjugate worm, thereby transforming sliding friction into rolling friction. This transformation can significantly improve load capacity, eliminate backlash, reduce wear, and extend service life. However, achieving optimal performance in this worm gear drive depends heavily on the selection of design parameters, which is a complex problem due to the interplay between geometric and kinematic factors. In this article, I will detail my approach to optimizing these parameters, based on differential geometry and spatial gearing theory, using a multi-objective genetic algorithm. The goal is to provide a scientific method for parameter selection that enhances meshing and lubrication performance, laying a foundation for further research and development in this field.

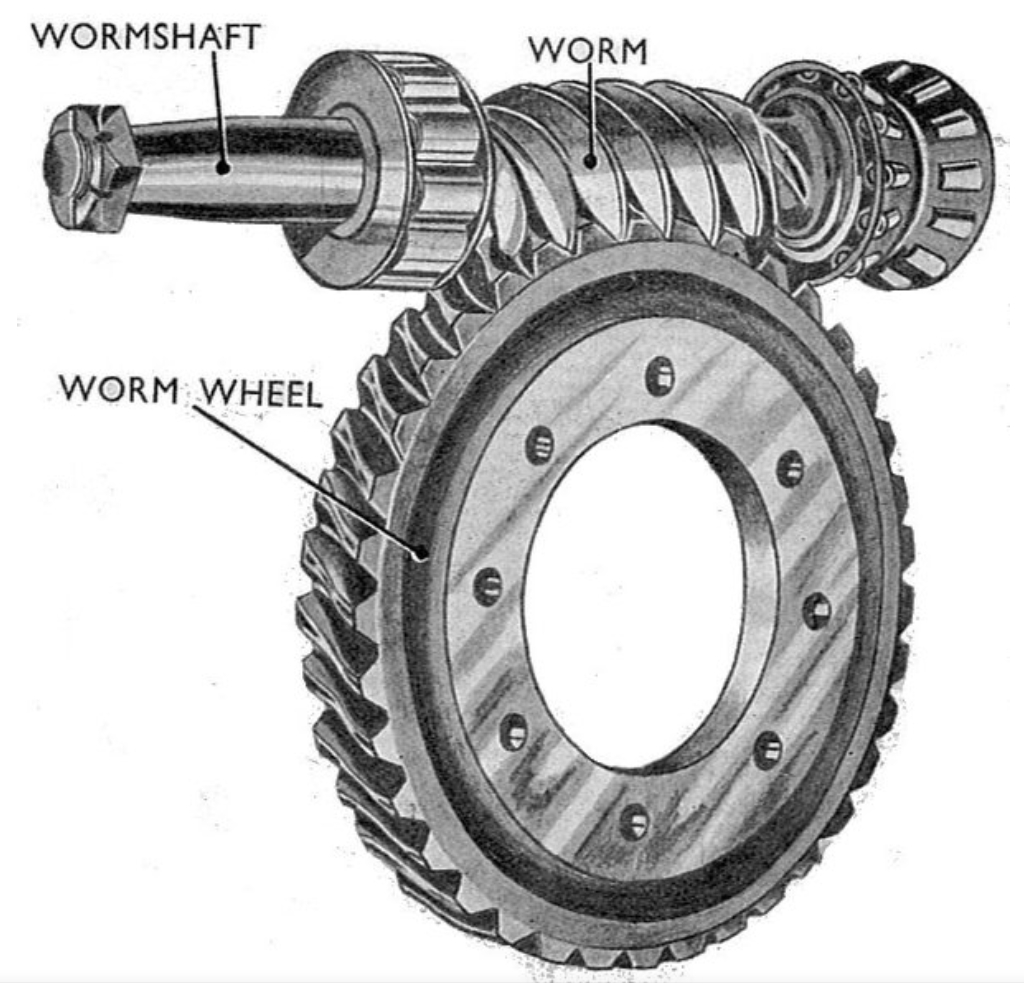

To begin, I established a comprehensive mathematical model to analyze the meshing characteristics of the roller enveloping end face engagement worm gear drive. This model is essential for understanding how parameters influence performance and for formulating optimization criteria. I set up coordinate systems as shown in the figure below, which illustrates the spatial relationships between the worm and worm wheel. The coordinate systems include static and dynamic frames for both components, allowing for the derivation of key equations. The worm gear drive involves a worm with a helical thread that meshes with a worm wheel featuring roller teeth. The rollers are positioned on the worm wheel’s end face, and their interaction with the worm surface determines the drive’s efficiency and durability.

In my model, I defined several coordinate systems: σ1 (i1, j1, k1) as the static coordinate system for the worm, σ2 (i2, j2, k2) for the worm wheel, and dynamic systems σ1′ and σ2′ that rotate with the components. The worm rotates about axis k1 with angular velocity ω1, while the worm wheel rotates about axis k2 with angular velocity ω2. The transmission ratio is given by i12 = ω1/ω2 = Z2/Z1, where Z1 is the number of worm threads and Z2 is the number of worm wheel teeth. The center distance is denoted as A. For the roller, I placed a coordinate system σ0 at the center of its cylindrical top. Using these frames, I derived the meshing function based on the principle of gear engagement, which is fundamental to analyzing the worm gear drive.

The meshing function for the worm gear drive can be expressed as the dot product of the normal vector and the relative velocity between the worm and worm wheel surfaces. Specifically, the condition for contact is given by:

$$ \Phi = \mathbf{n} \cdot \mathbf{V}^{(1’2′)} = 0 $$

where \(\mathbf{n}\) is the unit normal vector at the contact point, and \(\mathbf{V}^{(1’2′)}\) is the relative velocity vector between the worm and worm wheel in the dynamic coordinate systems. Through coordinate transformations and geometric relations, I obtained the explicit form of the meshing function:

$$ \Phi = M_1 \cos \phi_2 + M_2 \sin \phi_2 + M_3 = 0 $$

with:

$$ M_1 = \sin \theta (a_2 – u), \quad M_2 = 0, \quad M_3 = -i_{21} \cos \theta (a_2 – u) – A \sin \theta $$

Here, \(\phi_2\) is the rotation angle of the worm wheel, \(\theta\) is a parameter related to the roller’s position, \(u\) is the radial distance on the roller surface, and \(a_2\) is a coordinate of the roller center in the worm wheel system. This equation governs the contact conditions in the worm gear drive and is used to derive further performance metrics.

Next, I derived the contact line equations, which describe the instantaneous lines of contact between the worm and worm wheel surfaces. For a fixed \(\phi_2\), the contact line on the roller surface satisfies both the roller equation and the meshing equation. The parametric form is:

$$ \mathbf{r}_0 = x_0 \mathbf{i}_0 + y_0 \mathbf{j}_0 + z_0 \mathbf{k}_0, \quad u = f(\theta, \phi_2) = \frac{P_1}{P_2}, \quad \phi_2 = \text{constant} $$

These contact lines are crucial for assessing the load distribution and wear patterns in the worm gear drive. Additionally, I analyzed boundary functions to avoid undercutting and interference. The second-kind boundary function, which identifies limits on the meshing zone, is given by:

$$ \Phi_t = \frac{\partial \Phi}{\partial t} = -M_1 \sin \phi_2 \frac{d\phi_2}{dt} + M_2 \cos \phi_2 \frac{d\phi_2}{dt} = -M_1 \omega_2′ \sin \phi_2 + M_2 \omega_2′ \cos \phi_2 $$

The condition for the second boundary curve is:

$$ \Phi = 0 \quad \text{and} \quad \Phi_t = 0 $$

which simplifies to:

$$ M_1^2 + M_2^2 = M_3^2 $$

This equation helps determine the feasible meshing region for the worm gear drive. The first-kind boundary function, related to undercutting, involves more complex determinants but is essential for ensuring manufacturability and strength.

To evaluate the lubrication performance of the worm gear drive, I calculated the induced normal curvature along the contact line. Using the moving frame method, the induced normal curvature \(k_\delta^{(1’2′)}\) is:

$$ k_\delta^{(1’2′)} = – \frac{(\omega_2^{(1’2′)} + V_1^{(1’2′)}/R)^2 + (\omega_1^{(1’2′)})^2}{\Psi} $$

where \(\omega_1^{(1’2′)}\) and \(\omega_2^{(1’2′)}\) are components of the relative angular velocity, \(V_1^{(1’2′)}\) is the relative velocity component, \(R\) is the roller radius, and \(\Psi\) is a determinant from the meshing equations. A smaller induced curvature generally indicates better load distribution and lower contact stress in the worm gear drive.

The lubrication angle \(\mu\) is another key parameter, defined as the angle between the relative velocity vector and the contact line normal. It influences the formation of elastohydrodynamic lubrication films. I derived the formula:

$$ \mu = \sin^{-1} \left| \frac{V_1^{(1’2′)}(V_1^{(1’2′)}/R – \omega_2^{(1’2′)}) + V_2^{(1’2′)} \omega_1^{(1’2′)}}{\sqrt{(V_1^{(1’2′)})^2 + (V_2^{(1’2′)})^2} \sqrt{(V_1^{(1’2′)}/R – \omega_2^{(1’2′)})^2 + (\omega_1^{(1’2′)})^2}} \right| $$

For optimal lubrication in the worm gear drive, \(\mu\) should be close to 90°, as this promotes oil entrainment and reduces friction. Additionally, I computed the relative entrainment velocity \(V_{1′}\) at the contact point, which affects the oil film thickness. In the moving frame, this velocity has components:

$$ V_{1′}^1 = -\sin \phi_2 (y_0 \sin \theta + x_0 \cos \theta) + \cos \phi_2 (a_2 – z_0) \cos \theta – A \cos \theta $$

$$ V_{1′}^2 = \cos \phi_2 y_0 $$

$$ V_{1′}^n = \sin \phi_2 (\cos \theta y_0 – \sin \theta x_0) + \cos \phi_2 (a_2 – z_0) \sin \theta – A \sin \theta $$

A higher entrainment velocity can enhance lubrication in the worm gear drive. Finally, the self-rotation angle \(\mu_{z0}\), which favors roller spinning, is given by:

$$ \mu_{z0} = \arccos \frac{|v_2^{(12)}|}{\sqrt{(v_1^{(12)})^2 + (v_2^{(12)})^2}} $$

where \(v_1^{(12)}\) and \(v_2^{(12)}\) are relative velocity components. A value close to 90° indicates conditions conducive to roller self-rotation, reducing sliding friction in the worm gear drive.

With these performance equations established, I proceeded to the parameter optimization design for the worm gear drive. The goal was to select design variables that maximize meshing and lubrication performance while satisfying constraints. Based on my analysis, the most influential variables are the roller radius \(R\) and the worm throat diameter coefficient \(k_1\). Other parameters, such as the number of teeth \(Z_2\) and center distance \(A\), are often predetermined in practical worm gear drive applications. Therefore, I defined the optimization vector as:

$$ \mathbf{x} = [x_1, x_2]^T = [R, k_1]^T $$

To formulate the optimization problem, I considered two primary objectives: minimizing the induced normal curvature to reduce contact stress and maximizing the lubrication angle to improve oil film formation. However, these objectives may conflict, so I used a multi-objective approach. Based on the Dowson formula for elastohydrodynamic lubrication, the minimum oil film thickness \(h_0\) is proportional to \(v_{jx}^{0.7} / k_\delta^{0.43}\), where \(v_{jx}\) is the entrainment velocity component and \(k_\delta\) is the induced curvature. Thus, to maximize \(h_0\) in the worm gear drive, I constructed the first objective function:

$$ \min f_1(\mathbf{x}) = \frac{k_\delta^{0.43}}{v_{jx}^{0.7}} $$

For the lubrication angle, I aimed to bring \(\mu\) closer to 90°, so the second objective function is:

$$ \min f_2(\mathbf{x}) = \left| \frac{\pi}{2} – \mu \right| $$

To combine these into a single objective, I employed a linear weighting method, resulting in:

$$ \min f(\mathbf{x}) = a_1 \cdot f_1(\mathbf{x}) + a_2 \cdot f_2(\mathbf{x}) $$

where \(a_1\) and \(a_2\) are weighting coefficients. In my study, I set \(a_1 = 0.6\) and \(a_2 = 0.4\) to balance the importance of curvature and lubrication in the worm gear drive. The optimization seeks to minimize \(f(\mathbf{x})\) subject to constraints.

The constraints for the worm gear drive optimization include both variable bounds and performance limits. First, the variables must lie within practical ranges:

- Roller radius: \(4 \, \text{mm} \leq R \leq 11 \, \text{mm}\)

- Throat diameter coefficient: \(0.15 \leq k_1 \leq 0.5\)

These bounds ensure manufacturability and compatibility in the worm gear drive. Second, inequality constraints are imposed based on performance criteria. The lubrication angle should not fall below a permissible value to maintain adequate lubrication:

$$ g_1(\mathbf{x}) = [\mu] – \mu \leq 0 $$

where \([\mu]\) is the allowable lubrication angle, typically set to 82° for worm gear drives. Additionally, the worm’s strength and stiffness must be considered to prevent failure. A constraint based on center distance \(A\) and throat coefficient \(k_1\) is:

$$ g_2(\mathbf{x}) = 0.5 A^{0.895} – k_1 A \leq 0 $$

This ensures the worm in the worm gear drive has sufficient structural integrity under load.

To solve this optimization problem, I applied a genetic algorithm (GA), which is effective for handling non-linear, multi-objective functions. I used binary encoding with 18 bits per variable, providing precision to four decimal places. The fitness function was designed to handle constraints via a penalty method. Specifically, I defined:

$$ F(\mathbf{x}) = f(\mathbf{x}) + \Delta \sum_{j=1}^{2} \left( \min[g_j(\mathbf{x}), 0] \right)^2 $$

where \(\Delta\) is a penalty coefficient set to a large value (e.g., 1000) to penalize infeasible solutions. Since GA typically maximizes fitness, I converted it to:

$$ f_s = \frac{1}{F(\mathbf{x})} $$

Higher fitness values correspond to better solutions in the worm gear drive optimization. I implemented this in MATLAB using the Genetic Algorithm Toolbox, running iterations until convergence.

For a concrete example, I considered a worm gear drive with the following basic parameters, as summarized in Table 1:

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Center distance, \(A\) (mm) | 125 |

| Worm threads, \(Z_1\) | 1 |

| Worm wheel teeth, \(Z_2\) | 25 |

| Addendum coefficient, \(h_a^*\) | 0.8 |

| Dedendum coefficient, \(h_f^*\) | 0.8 |

| Clearance coefficient, \(c^*\) | 0.2 |

Using traditional design methods for this worm gear drive, I selected parameters based on prior meshing analysis: roller radius \(R = 10.5 \, \text{mm}\) and throat coefficient \(k_1 = 0.15\). However, these may not be optimal for overall performance.

Applying the genetic algorithm, I obtained optimized parameters after 16 iterations. The results are shown in Table 2:

| Roller Radius \(R\) (mm) | Throat Coefficient \(k_1\) | Objective Function \(f(\mathbf{x})\) | Constraint \(g_1(\mathbf{x})\) | Constraint \(g_2(\mathbf{x})\) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11.0000 | 0.3012 | 0.0064 | -8 | -1.8626e-006 |

The exit flag indicated convergence to a solution. For practical implementation in the worm gear drive, I rounded these to \(R = 11 \, \text{mm}\) and \(k_1 = 0.3\).

To evaluate the improvement, I compared the meshing performance of the worm gear drive using traditional parameters versus optimized parameters. Key performance metrics include induced normal curvature, lubrication angle, relative entrainment velocity, and self-rotation angle. The comparisons are summarized below:

- Induced Normal Curvature: The optimized worm gear drive shows a reduction of approximately 0.0183 mm⁻¹, indicating lower contact stress and better load distribution.

- Lubrication Angle: The average lubrication angle increased by about 0.2842°, bringing it closer to 90° and enhancing oil film formation.

- Self-Rotation Angle: This angle increased by 0 to 3.27°, promoting roller spinning and reducing sliding friction.

- Relative Entrainment Velocity: While not tabulated here, the optimized parameters generally yield higher velocities, contributing to thicker lubrication films.

These improvements demonstrate that the optimized worm gear drive achieves superior meshing and lubrication performance compared to the traditional design. The genetic algorithm effectively balances multiple objectives, leading to parameters that enhance the worm gear drive’s durability and efficiency.

In conclusion, my research on the roller enveloping end face engagement worm gear drive has led to a robust framework for parameter optimization. By integrating differential geometry and gearing theory, I derived comprehensive performance equations that capture the complex interactions in this worm gear drive. The multi-objective optimization model, solved via genetic algorithm, provides a scientific method for selecting design parameters that improve contact and lubrication characteristics. This approach addresses the challenges in worm gear drive design, such as balancing curvature and lubrication angles, while satisfying practical constraints. The results show significant performance gains, validating the effectiveness of the optimization. This work not only advances the understanding of this specific worm gear drive but also offers a methodology applicable to other types of gear systems. Future research can build on this foundation, exploring additional factors like thermal effects or dynamic loads, to further enhance the worm gear drive’s performance in real-world applications.

Throughout this article, I have emphasized the importance of the worm gear drive in mechanical transmissions and detailed the steps taken to optimize its parameters. The use of mathematical models, optimization algorithms, and performance comparisons underscores the value of a systematic approach in engineering design. By sharing these insights, I hope to contribute to the ongoing development of more efficient and reliable worm gear drives for various industrial uses.