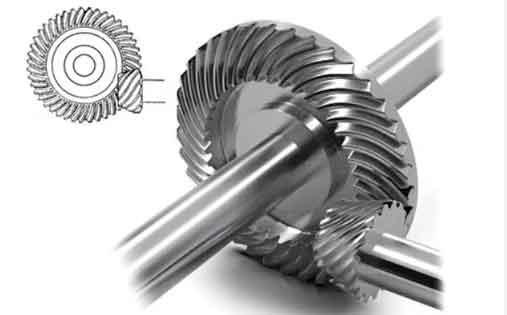

The manufacturing of spiral bevel gears is a sophisticated process critical for power transmission in aerospace, automotive, and heavy machinery applications. Achieving high precision and longevity in these gears heavily depends on the quality of the finishing operation, which is, in turn, preconditioned by the preceding roughing cut. The primary objective of the roughing stage is to efficiently remove bulk material from the gear blank, leaving behind a precisely controlled and uniform layer of material—the finishing allowance—for the subsequent finishing cut. An uneven finishing allowance can lead to several detrimental effects: it accelerates tool wear during finishing, introduces residual stresses and potential distortions, and ultimately compromises the final gear’s surface integrity, contact pattern, and noise performance. Therefore, developing an optimization methodology for the pinion roughing process to ensure a predictable and uniform finishing allowance is of paramount importance for enhancing manufacturing efficiency and product quality in spiral bevel gear production.

The challenge is particularly acute for the pinion in a spiral bevel gear pair. Unlike the gear (larger wheel), which is typically finished using a duplex or spread-blade method leaving a relatively symmetric allowance, the pinion is finished using a single-indexing, two-cut process. This means its convex and concave flanks are machined in separate operations with distinct machine tool settings and a single-sided cutter. However, the roughing of the pinion is performed in a single operation using a double-sided (interlocking) cutter to create the entire tooth slot. The fundamental problem is that a single set of roughing parameters must approximate two distinct theoretical finishing surfaces. Traditional methods, such as those provided in legacy manufacturing guidelines, often rely on empirical formulas and fixed correlations between finishing and roughing settings. These methods may not yield an optimal or even sufficient result, potentially leading to non-uniform stock distribution, excessive cutting forces, and in worst-case scenarios, cutter interference or insufficient material left for finishing. This work presents a systematic, computational optimization approach to determine the pinion roughing parameters that minimize the deviation between the actual rough-cut surface and a predefined “target” roughing surface, thereby guaranteeing a uniform finishing allowance.

Theoretical Foundation and Modeling

1. Definition of the Finishing Surface and Workpiece Localization

The starting point for optimizing the roughing process is a precise mathematical definition of the desired final pinion tooth flanks. The geometry of a spiral bevel gear tooth surface generated by a cradle-style hypoid generator can be described using the theory of gearing, coordinate transformations, and the equation of meshing. For the finishing operation of a pinion flank (concave or convex), the surface $\Sigma_f$ is defined by the vector function:

$$ \mathbf{r}_{1f} = \mathbf{r}_{1f}(u_f, \theta_f, \phi_f) $$

where $u_f$ and $\theta_f$ are the tool surface parameters, $\phi_f$ is the work rotation angle (generating roll), and $\mathbf{r}_{1f}$ is the position vector of a point on the finished pinion tooth surface in the pinion coordinate system. This vector is derived through a series of coordinate transformations from the cutter to the workpiece. The equation of meshing $f_{1f}(u_f, \theta_f, \phi_f)=0$ must also be satisfied, ensuring conjugacy between the cutter and the generated gear surface.

Since the convex and concave flanks of the pinion are generated independently, they do not inherently form a coherent tooth. They must be rotationally aligned relative to each other based on the gear blank design specifications. This alignment is performed using the pinion’s midpoint inspection dimensions: midpoint chordal tooth thickness $s_{n1}$ and midpoint chordal addendum $h_{m1}$. A computational procedure is employed:

- Define a grid of evaluation points (e.g., 5×9 grid) on the pinion’s rotated projection plane, specified by radial and lengthwise coordinates $(R_i, L_i)$.

- For each target point $(R_i, L_i)$ on a given flank, solve a system of nonlinear equations to find the corresponding finishing surface parameters $(u_f, \theta_f, \phi_f)$ and the surface point $\mathbf{p}_i^{finish}$.

- Using the midpoint chordal addendum formula, locate the specific contact points $\mathbf{p}_v$ (on the concave flank) and $\mathbf{p}_x$ (on the convex flank) corresponding to the inspection gauges.

- Calculate the required rotational alignment angle $\theta_s$ for one flank (e.g., the concave) so that the distance between the aligned contact points equals the specified chordal tooth thickness $s_{n1}$:

$$ \| \mathbf{Rot}(\theta_s) \cdot \mathbf{p}_v – \mathbf{p}_x \| = s_{n1} $$

where $\mathbf{Rot}(\theta_s)$ is the rotation operator. Applying this rotation aligns both theoretical finishing surfaces to their correct relative position on the physical gear blank.

2. Construction of the Target Roughing Surface

Once the aligned finishing surfaces are established, the target roughing surface is defined. For a specified uniform finishing allowance $\delta$ (a scalar value, e.g., 0.2 mm), the target roughing surface is obtained by offsetting the finishing surface inward (towards the tooth interior) along its local unit normal vector $\mathbf{n}_i$ at each grid point:

$$ \mathbf{p}_i^{target} = \mathbf{p}_i^{finish} + \delta \cdot \mathbf{n}_i $$

This operation is performed independently for all grid points on both the convex and concave flanks. The collection of points $\mathbf{p}_i^{target}$ defines the desired geometry that the roughing cut should ideally produce. The unit normal vector $\mathbf{n}_i$ is computed from the partial derivatives of the finishing surface:

$$ \mathbf{n}_i = \frac{\mathbf{r}_{1f, u_f} \times \mathbf{r}_{1f, \theta_f}}{\|\mathbf{r}_{1f, u_f} \times \mathbf{r}_{1f, \theta_f}\|} $$

evaluated at the corresponding parameters for point $i$.

3. Mathematical Model of the Roughing Process

The roughing process for spiral bevel gears uses a double-sided cutter and a single continuous cutting cycle. Its mathematical model is analogous to the finishing model but with a different set of machine tool settings ($\mathbf{S}_{rough}$) and cutter geometry ($\mathbf{C}_{rough}$). The generated roughing surface $\Sigma_r$ is given by:

$$ \mathbf{r}_{1r} = \mathbf{r}_{1r}(u_r, \theta_r, \phi_r; \mathbf{S}_{rough}, \mathbf{C}_{rough}) $$

subject to its own equation of meshing $f_{1r}(u_r, \theta_r, \phi_r; \mathbf{S}_{rough}, \mathbf{C}_{rough})=0$.

For a given set of roughing parameters, we can compute the position $\mathbf{p}_j^{rough}(\mathbf{S}_{rough}, \mathbf{C}_{rough})$ and normal $\mathbf{n}_j^{rough}$ for points on the rough-cut surface. Since the roughing cutter generates both flanks of a tooth slot simultaneously, an additional rotational transformation is needed to compare its output (a tooth slot) with the target geometry (a tooth). This is typically done by fixing one flank of the rough-cut slot and rotating the opposite flank by $2\pi/z_1$ (where $z_1$ is the pinion tooth number) to form a “rough tooth,” which is then rotationally aligned to the target tooth for comparison.

4. Optimization Problem Formulation

The core of the methodology is to find the set of roughing parameters that makes the actually cut rough surface as close as possible to the target roughing surface. This is formulated as a nonlinear least-squares optimization problem. The design variables ($\mathbf{x}$) are key roughing machine settings, such as:

- Machine Center to Back (MCB) or Sliding Base Setting.

- Vertical Offset (VRT) or Work Offset.

- Horizontal Offset (HOR) or Cradle Offset.

- Cutter Point Width (PW).

- Modified Roll Coefficients.

The cutter radius and blade angles are usually fixed based on available tooling.

For a set of $N$ corresponding point pairs on the target and rough surfaces, we define the error $e_i$ as the signed distance from the rough surface point to the target surface along the target surface normal:

$$ e_i(\mathbf{x}) = (\mathbf{p}_i^{target} – \mathbf{p}_i^{rough}(\mathbf{x})) \cdot \mathbf{n}_i^{target} $$

The objective function $F(\mathbf{x})$ to be minimized is the sum of squared errors:

$$ F(\mathbf{x}) = \frac{1}{2} \sum_{i=1}^{N} [e_i(\mathbf{x})]^2 = \frac{1}{2} \mathbf{e}(\mathbf{x})^T \mathbf{e}(\mathbf{x}) $$

This minimization problem is subject to bounds on the design variables (physical limits of the machine) and must also satisfy the geometric constraint that the roughing cutter does not gouge or interfere with the target surface.

5. Solution Algorithm: Trust-Region Levenberg-Marquardt Method

Solving the nonlinear least-squares problem requires a robust and efficient algorithm. The Levenberg-Marquardt (L-M) algorithm, enhanced with a trust-region strategy, is particularly well-suited. It interpolates between the Gauss-Newton method and the method of steepest descent, providing stable convergence even far from the optimum.

The algorithm iteratively updates the parameter vector $\mathbf{x}$:

$$ \mathbf{x}_{k+1} = \mathbf{x}_k + \mathbf{d}_k $$

where the step $\mathbf{d}_k$ is determined by solving:

$$ (\mathbf{J}_k^T \mathbf{J}_k + \lambda_k \mathbf{I}) \mathbf{d}_k = -\mathbf{J}_k^T \mathbf{e}(\mathbf{x}_k) $$

Here, $\mathbf{J}_k$ is the Jacobian matrix of the error vector $\mathbf{e}$ with respect to $\mathbf{x}$ at iteration $k$, $\mathbf{I}$ is the identity matrix, and $\lambda_k$ is a damping parameter. The trust-region strategy adaptively controls $\lambda_k$: a small $\lambda$ promotes fast Gauss-Newton convergence when the model is accurate within a trusted region, while a large $\lambda$ enforces a cautious gradient-descent step when the model is unreliable. The Jacobian matrix $\mathbf{J}$ is computed efficiently using finite differences or, if available, analytical derivatives based on the kinematics of the gear generator.

Numerical Investigation and Case Study

To validate the proposed optimization method, a case study was conducted on a spiral bevel pinion. The gear pair was designed using the Formate (for the gear) and Generate (for the pinion) principles, with a pinion tooth count of 23. A uniform finishing allowance of $\delta = 0.2$ mm was prescribed.

| Parameter | Concave Flank | Convex Flank |

|---|---|---|

| Cutter Radius (mm) | 190.5123 | 190.7483 |

| Cutter Blade Angle (deg) | 18.0 | 22.0 |

| Radial Setting (mm) | 108.2268 | 119.3134 |

| Vertical Offset (mm) | -6.2747 | 4.5378 |

| Machine Root Angle (deg) | 18.3282 | 18.3282 |

| Cradle Angle (deg) | 49.4733 | 48.4926 |

Several roughing strategies were investigated and compared:

- Conventional Gleason-Based Settings: Using standard handbook correlations between finishing and roughing parameters.

- Optimized Settings with Fixed Cutter: Applying the L-M optimization to key machine settings (VRT, HOR, MCB) while using the standard double-sided cutter geometry (18°/22° blade angles, fixed point width).

- Fully Optimized Settings: Extending the optimization to include the cutter Point Width (PW) as a design variable, in addition to the machine settings.

- Non-Standard Cutter Strategy: Investigating the use of the gear’s roughing cutter (typically with equal 20°/20° blade angles) for the pinion, with and without point width optimization.

| Strategy | Key Characteristic | Optimized Variables | RMS Finishing Allowance Error (mm) | Midpoint Whole Depth (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Conventional | Handbook values | None | 0.0339 | 6.25 |

| 2. Opt. Machine Settings | Standard pinion cutter | VRT, HOR, MCB | 0.0187 | 6.30 |

| 3. Fully Optimized | Standard pinion cutter | VRT, HOR, MCB, PW | 0.0171 | 6.40 |

| 4. Gear Cutter (Fixed PW) | 20°/20° blade angles | VRT, HOR, MCB | 0.0227 | 6.22 |

| 5. Gear Cutter (Opt. PW) | 20°/20° blade angles | VRT, HOR, MCB, PW | 0.0197 | 6.24 |

The results are clear and significant. The conventional method (Strategy 1) yielded the least uniform allowance, with a root-mean-square (RMS) error of 33.9 μm. This non-uniformity stems from the fixed, approximate nature of the handbook correlations which do not account for the specific geometry of the pinion finishing surfaces. Optimizing only the machine settings (Strategy 2) drastically improved uniformity, reducing the RMS error to 18.7 μm. Allowing the cutter point width to be optimized (Strategy 3) provided a further, albeit smaller, improvement to 17.1 μm. The fully optimized strategy also resulted in a larger midpoint whole tooth depth, meaning more material was correctly removed during roughing, leaving a more consistent layer for finishing.

A critical finding concerns the use of non-standard cutters. Strategies 4 and 5 simulated using the gear’s roughing cutter (20°/20° blades) for the pinion. Even with optimization, the RMS error remained higher (22.7 and 19.7 μm) than when using the correct pinion cutter. Analysis of the error distribution revealed a systematic profile error across the tooth flank. This is a direct consequence of the blade angle mismatch; the 20°/20° cutter cannot perfectly approximate the geometry defined by 18°/22° finishing surfaces, even with adjusted machine positions. The optimization minimizes the overall error but cannot eliminate this inherent kinematic discrepancy. This demonstrates that while optimization can compensate significantly, starting with a kinematically appropriate cutter geometry is fundamentally important for achieving the highest precision in spiral bevel gear manufacturing.

Experimental Validation

To physically validate the numerical findings, a cutting trial was performed on a modern CNC spiral bevel gear generator. The pinion was machined according to the most pragmatic optimized scenario: using the available gear roughing cutter (20°/20°) but with fully optimized machine settings and point width (Strategy 5). The roughing was executed in two passes with different depth settings to manage cutting forces. Subsequently, the pinion was finished using its dedicated single-sided cutters and the prescribed finishing machine settings from Table 1.

Post-machining inspection focused on the critical midpoint dimensions. The measured chordal addendum and whole depth showed excellent agreement with the predicted values from the optimization model, confirming the accuracy of the surface positioning algorithm. Visual inspection and subsequent rolling tests indicated a well-formed tooth profile and a coherent tooth slot geometry from the roughing operation. The successful trial confirms that the proposed optimization method is not merely a theoretical exercise but a practical tool that can be directly implemented on shop-floor machinery to improve the roughing process for spiral bevel gears, even when using slightly non-ideal tooling.

Conclusion

This work has developed and demonstrated a comprehensive, computational methodology for optimizing the roughing parameters of spiral bevel gear pinions. The method directly addresses the core challenge of ensuring a uniform finishing allowance by formulating it as a nonlinear least-squares fitting problem between a calculated target roughing surface and the manufacturable roughing surface model. The use of the Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm with a trust-region strategy provides a robust and efficient numerical solution.

The key conclusions are:

- Superior Performance over Conventional Methods: Optimizing key machine settings such as Vertical Offset (VRT), Horizontal Offset (HOR), and Machine Center to Back (MCB) yields a significantly more uniform finishing allowance compared to traditional handbook-based settings for spiral bevel gears. This translates directly to longer finishing tool life, more stable finishing cuts, and improved final gear quality.

- Value of Cutter Parameter Optimization: Including the cutter Point Width (PW) as an optimization variable provides an additional degree of freedom, leading to a marginal further improvement in allowance uniformity and a more accurate pre-finish tooth depth.

- Importance of Cutter Geometry Selection: The study clearly shows that using a roughing cutter with blade angles mismatched to the final tooth form (e.g., a gear cutter on a pinion) introduces a inherent, systematic profile error in the finishing allowance. While parameter optimization can mitigate this error, it cannot eliminate it entirely. Therefore, for highest-precision applications of spiral bevel gears, using a dedicated pinion roughing cutter with blade angles derived from the finishing design remains essential.

The presented methodology offers a clear path towards more intelligent, model-driven manufacturing of spiral bevel gears. By replacing empirical rules with physics-based simulation and numerical optimization, manufacturers can achieve greater consistency, reduce scrap rates, and enhance the performance of these critical power transmission components. Future work may integrate this approach with real-time process monitoring and adaptive control systems for closed-loop manufacturing of spiral bevel gears.