In my extensive experience with mechanical power transmission systems, I have often encountered the limitations of traditional减速机 designs, particularly in applications like automatic doors and barrier gates. These systems typically relied on AC减速机 coupled with braking mechanisms, which were bulky, complex, and costly. A significant drawback was their high power consumption when paired with backup battery systems, necessitating large batteries and inverters. The advent of permanent magnet DC减速机, often derived from automotive windshield wiper motors, promised a more compact solution. However, these早期 screw gear units suffered from low efficiency and inadequate load-bearing capacity. This drove me to undertake a comprehensive redesign of the screw gear transmission to overcome these deficiencies. This article details my first-person analysis and the resulting改进设计, focusing extensively on the screw gear pair’s mechanics.

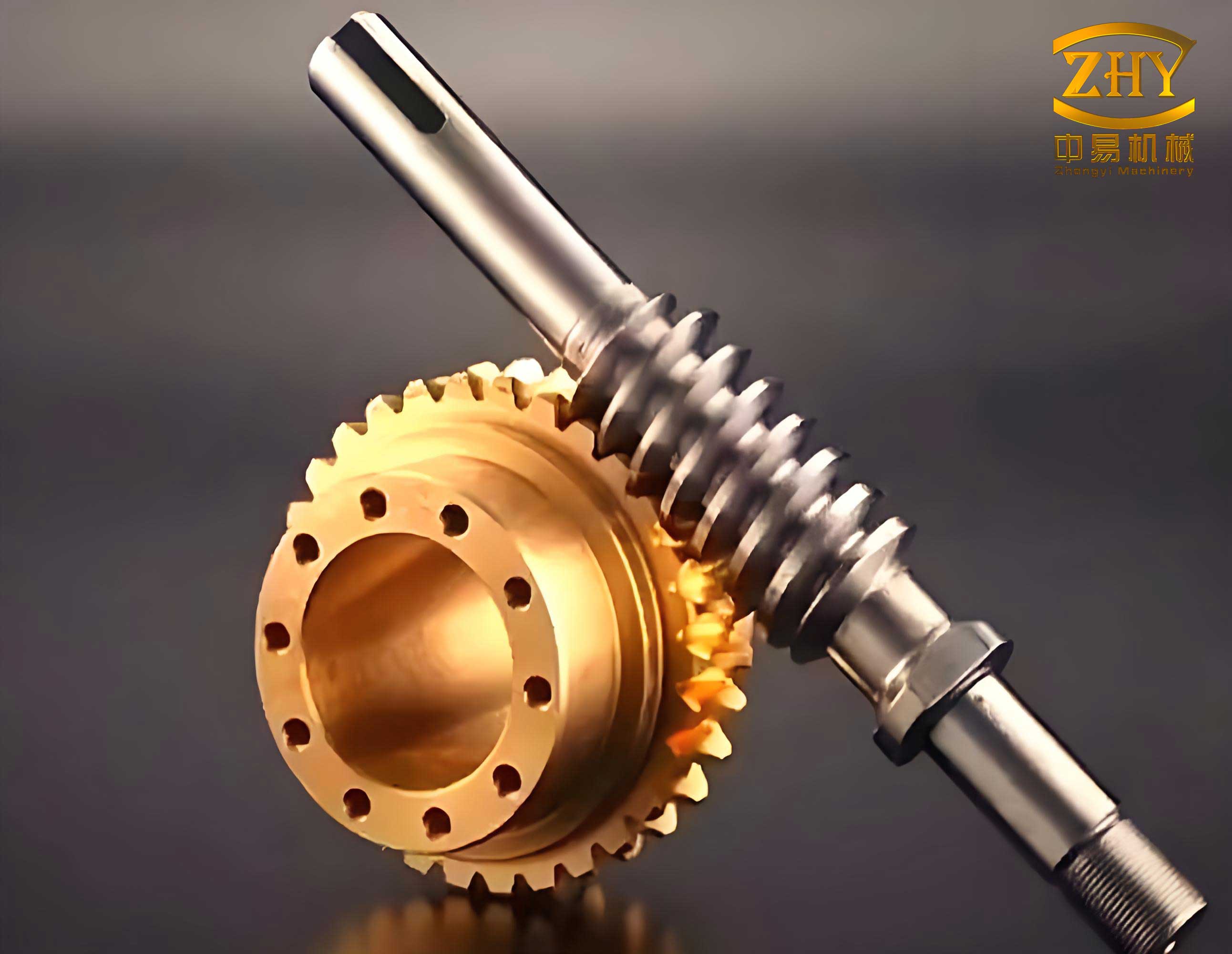

The core of any worm reducer is the screw gear meshing pair. A screw gear, commonly referred to as a worm and worm wheel, involves a helical thread (the worm) engaging with a toothed wheel (the worm gear). The primary advantage is high reduction ratio in a single stage, but this comes at the cost of sliding friction and potential efficiency losses. My redesign journey began with a fundamental re-examination of the forces and losses within this screw gear interaction.

A precise force analysis is paramount for understanding performance limitations. Let us consider a standard screw gear pair with the worm as the driving member. The forces acting on the worm can be broken down into three mutually perpendicular components: tangential force, axial force, and radial force. These are mirrored by corresponding forces on the worm wheel. The following equations govern these interactions for a right-handed worm driving clockwise:

The worm tangential force, $F_{t1}$, which is equal and opposite to the worm wheel axial force, $F_{x2}$, is given by:

$$F_{t1} = -F_{x2} = \frac{2000 T_1}{d_1}$$

Here, $T_1$ is the input torque on the worm in N·m, and $d_1$ is the worm’s reference diameter in mm. This force opposes the input torque.

The worm axial force, $F_{x1}$, equating to the worm wheel tangential force, $F_{t2}$, is:

$$F_{x1} = -F_{t2} = -\frac{2000 T_2}{d_2 + 2x_2 m}$$

In this equation, $T_2$ is the output torque on the worm gear in N·m, $d_2$ is the worm gear reference diameter in mm, $x_2$ is the profile shift coefficient, and $m$ is the axial module. The force $F_{t2}$ creates a torque opposing the output torque $T_2$.

The radial forces on both members, $F_{r1}$ and $F_{r2}$, are equal and act towards their respective centers:

$$F_{r1} = -F_{r2} = -F_{t2} \tan(\alpha_x)$$

The term $\alpha_x$ represents the axial pressure angle of the worm.

The resultant normal force $F_n$, acting perpendicular to the tooth flank at the meshing point, is crucial for friction calculations:

$$F_n = \frac{F_{x1}}{\cos(\gamma) \cos(\alpha_n)} \approx -\frac{F_{t2}}{\cos(\gamma) \cos(\alpha_x)} = -\frac{2000 T_2}{d_2 \cos(\gamma) \cos(\alpha_x)}$$

Here, $\gamma$ is the lead angle of the worm, and $\alpha_n$ is the normal pressure angle.

The efficiency $\eta$ of the screw gear drive, with the worm as the driver, is primarily a function of the lead angle and the equivalent friction angle $\rho_v$:

$$\eta = \frac{\tan \gamma}{\tan(\gamma + \rho_v)}$$

This formula immediately highlights a key insight: increasing the lead angle $\gamma$ can potentially improve efficiency, provided other losses are managed.

Sliding velocity $V_s$ at the mesh is significantly higher than the worm’s tangential velocity, contributing to wear and friction:

$$V_s = \frac{V_1}{\cos \gamma} = \frac{\pi d_1 n_1}{60000 \cos \gamma} = \frac{\pi m n_1 Z_1}{60000 \sin \gamma}$$

In this expression, $n_1$ is the worm speed in rpm, and $Z_1$ is the number of worm threads (starts).

The frictional force $F_f$ at the screw gear interface is:

$$F_f = \mu F_n = \frac{2000 \mu T_2}{d_2 \cos(\gamma) \cos(\alpha_x)}$$

where $\mu$ is the coefficient of friction. Consequently, the power loss $P_{loss}$ due to this friction is:

$$P_{loss} = F_f V_s = \frac{2000 \mu T_2 \cdot \pi m n_1 Z_1}{60000 \cdot d_2 \cos(\gamma) \sin(\gamma) \cos(\alpha_x)} = \frac{4000 \pi \mu T_2 m n_1 Z_1}{60000 \cdot d_2 \sin(2\gamma) \cos(\alpha_x)}$$

Simplifying the constants:

$$P_{loss} \approx \frac{0.1047 \mu T_2 m n_1 Z_1}{d_2 \sin(2\gamma) \cos(\alpha_x)}$$

This relationship is critical. It shows that to minimize power loss in a screw gear, we must reduce the friction coefficient $\mu$, optimize the module $m$ and worm diameter $d_2$, and most importantly, increase the term $\sin(2\gamma)$ by selecting a larger lead angle $\gamma$ and reduce $\cos(\alpha_x)$ by using a smaller pressure angle.

Another vital aspect often overlooked in small screw gear motors is worm shaft deflection. Excessive deflection misaligns the mesh, increasing wear, noise, and reducing efficiency. The deflection $y$ at the worm’s midpoint depends on the support configuration. For a worm shaft supported at both ends (simply supported), the deflection due to the resultant of tangential and radial forces is:

$$y_{both} = \frac{\sqrt{F_{t1}^2 + F_{r1}^2} \cdot L^3}{48 E I}$$

For a cantilevered shaft (supported at one end only), the deflection is significantly worse:

$$y_{one} = \frac{\sqrt{F_{t1}^2 + F_{r1}^2} \cdot L^3}{24 E I}$$

In these formulas, $L$ is the span between supports (or overhang length for cantilever), $E$ is the modulus of elasticity, and $I$ is the area moment of inertia of the worm’s root diameter section. Clearly, adopting a two-bearing support system can halve the deflection for the same load, effectively doubling the perceived stiffness. Furthermore, from the radial force equation $F_{r1} = -F_{t2} \tan(\alpha_x)$, we see that reducing the pressure angle $\alpha_x$ directly reduces the radial load, thereby reducing deflection for a given geometry.

Guided by this analysis, my改进设计 focused on several interconnected parameters of the screw gear set. The traditional design used a relatively large worm diameter factor $q$ (where $q = d_1 / m$) and a conservative lead angle. To boost efficiency, I aimed to reduce $q$ and increase $\gamma$. However, a smaller $q$ means a smaller worm root diameter, reducing the area moment of inertia $I$ and compromising stiffness ($I \propto d_{root}^4$). To compensate, I employed a dual-module approach for calculating the screw gear geometry. The axial module $m_x$ governs the pitch and tooth size for meshing, but a larger “root module” can be conceptually used to design a larger root diameter for the worm, enhancing $I$ without altering the mesh geometry. Practically, this involves undercutting the worm thread less aggressively or using a specialized hob. The table below summarizes the key parameter changes in my optimized screw gear design compared to a conventional one from a wiper motor.

| Parameter | Conventional Design | Optimized Design | Design Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Worm Starts ($Z_1$) | 1 | 1 (or sometimes 2 for higher ratio) | Maintains high reduction ratio; multi-start can increase $\gamma$. |

| Axial Module ($m_x$) | 1.25 mm | 1.25 mm | Keeps physical size manageable. |

| Worm Diameter Factor ($q$) | ~12.5 | ~9.6 | Reduces worm diameter, increasing $\gamma$ for efficiency. |

| Lead Angle ($\gamma$) | ~7.5° | ~12° | Increases $\sin(2\gamma)$, directly reducing $P_{loss}$. |

| Axial Pressure Angle ($\alpha_x$) | 20° | 14° | Reduces radial force $F_r$ and normal force $F_n$, lowering friction and improving stiffness. |

| Normal Pressure Angle ($\alpha_n$) | 20° | ~13.7° | Corresponds to reduced axial pressure angle. |

| Worm Support | Often cantilevered | Two-bearing support | Halves deflection, greatly improving mesh alignment and load capacity. |

| Tooth Profile | Standard involute | Optimized flank geometry | Promotes better lubrication film formation. |

| Material & Hardness | Case-hardened steel | Premium alloy steel, nitrided | Increases surface hardness, reducing wear and friction coefficient $\mu$. |

The interplay of these parameters is complex. Increasing the lead angle $\gamma$ while decreasing the pressure angle $\alpha_x$ required careful checks for undercutting and tooth strength. The modified tooth profile of our optimized screw gear is visually distinct. The flanks are more rounded, and the pressure angle is notably smaller. This profile promotes a more favorable elastohydrodynamic lubrication regime. To illustrate the resulting screw gear morphology, consider the following representation:

The image shows the refined tooth form with a reduced pressure angle and a pronounced lead, key features of the high-efficiency screw gear design.

The theoretical gains were validated through practical application. For a specific automatic door drive unit requiring an output torque $T_2$ of 15 N·m at a worm speed $n_1$ of 3000 rpm, the performance improvement was quantified. Using the derived formulas, let’s calculate the friction loss for both designs, assuming an improved friction coefficient $\mu=0.04$ for the optimized design versus $\mu=0.06$ for the conventional one due to better hardening and lubrication.

Conventional Screw Gear Parameters: $m=1.25\text{mm}$, $Z_1=1$, $d_2=62.5\text{mm}$, $\gamma=7.5°$, $\alpha_x=20°$.

First, find the worm diameter $d_1 = q \cdot m = 12.5 \times 1.25 = 15.625\text{mm}$. The lead angle is given as 7.5°.

The normal force magnitude is:

$$F_n \approx \frac{2000 \times 15}{62.5 \times \cos(7.5°) \times \cos(20°)} = \frac{30000}{62.5 \times 0.9914 \times 0.9397} \approx 515.6 \text{ N}$$

The sliding velocity:

$$V_s = \frac{\pi \times 15.625 \times 3000}{60000 \times \cos(7.5°)} = \frac{\pi \times 15.625 \times 3000}{60000 \times 0.9914} \approx 2.48 \text{ m/s}$$

Friction loss power:

$$P_{loss, conv} = \mu F_n V_s = 0.06 \times 515.6 \times 2.48 \approx 76.7 \text{ W}$$

Optimized Screw Gear Parameters: $m=1.25\text{mm}$, $Z_1=1$, $d_2=62.5\text{mm}$ (same gear size for comparison), $\gamma=12°$, $\alpha_x=14°$. Worm diameter $d_1 = q \cdot m = 9.6 \times 1.25 = 12.0\text{mm}$.

Normal force:

$$F_n \approx \frac{2000 \times 15}{62.5 \times \cos(12°) \times \cos(14°)} = \frac{30000}{62.5 \times 0.9781 \times 0.9703} \approx 507.2 \text{ N}$$

Sliding velocity:

$$V_s = \frac{\pi \times 12.0 \times 3000}{60000 \times \cos(12°)} = \frac{\pi \times 12.0 \times 3000}{60000 \times 0.9781} \approx 1.93 \text{ m/s}$$

Friction loss power:

$$P_{loss, opt} = \mu F_n V_s = 0.04 \times 507.2 \times 1.93 \approx 39.2 \text{ W}$$

The reduction in friction loss is dramatic, from 76.7W to 39.2W, representing nearly a 49% decrease. This directly translates to higher overall efficiency. The total efficiency gain measured in the complete reducer assembly was around 6-8 percentage points, which is substantial for a screw gear system. For instance, if the conventional unit had an efficiency of 55%, the optimized screw gear drive achieved about 62%.

Stiffness was another triumph. By reducing the pressure angle from 20° to 14°, the radial force $F_{r1}$ for the same output torque drops. Using $F_{t2} = 2000 T_2 / d_2 = 2000*15/62.5 = 480N$ (approximately, neglecting shift for simplicity):

Conventional: $F_{r1, conv} = 480 \times \tan(20°) \approx 480 \times 0.3640 = 174.7 \text{ N}$

Optimized: $F_{r1, opt} = 480 \times \tan(14°) \approx 480 \times 0.2493 = 119.7 \text{ N}$

This is a 31.5% reduction in radial load. Combined with the two-bearing support, which effectively doubles stiffness compared to a cantilever, and the increased root diameter from the dual-module design, the worm shaft deflection was reduced by over 60%. This resulted in smoother operation, less audible noise, and significantly延长寿命 for the entire screw gear set.

The manufacturing and assembly considerations for this new screw gear are also noteworthy. The precise grinding of the worm with a reduced pressure angle requires specialized tools. Furthermore, the backlash and meshing depth must be carefully controlled during assembly. The worm wheel is typically made from a bronze alloy to accommodate the sliding friction, and its tooth profile must be conjugate to the modified worm profile. We developed a dedicated hob to generate the worm wheel teeth accurately. The table below outlines some critical tolerances and assembly checks for the optimized screw gearbox.

| Aspect | Specification | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Worm Tooth Profile Error | < 0.015 mm | Minimize vibration and localized contact stress. |

| Worm Lead Error | < 0.01 mm over 25 mm | Ensure consistent contact pattern across the worm wheel face. |

| Worm Wheel Runout | < 0.05 mm (T.I.R.) | Maintain uniform backlash. |

| Center Distance Tolerance | ± 0.03 mm | Critical for proper mesh depth and function of the screw gear pair. |

| Backlash (at operating temp) | 0.08 – 0.15 mm | Prevent binding while minimizing positional error. |

| Worm Shaft Axial Play | < 0.02 mm | Control axial movement that affects mesh. |

| Lubricant Type | Synthetic EP Grease (NLGI 2) | Provide extreme pressure (EP) protection for sliding contact. |

In conclusion, the systematic re-engineering of the screw gear transmission, driven by a deep dive into its force dynamics, loss mechanisms, and stiffness requirements, yielded a superior product. The synergistic effects of increasing the lead angle, reducing the pressure angle, employing a two-bearing worm support, and utilizing advanced materials resulted in a screw gear减速机 that is markedly more efficient, robust, and reliable. This optimized screw gear design has proven itself in field applications, providing longer service life and lower energy consumption. The principles outlined here—balancing geometric parameters to manage forces, friction, and deflection—are universally applicable to enhancing the performance of any power transmission system relying on a screw gear. Future work may explore multi-start worms for even higher efficiency or advanced polymer composites for the worm wheel to further reduce weight and friction. The humble screw gear, often taken for granted, holds significant potential for optimization, as demonstrated by this comprehensive redesign effort.

The journey of improving this screw gear has reinforced my belief that fundamental engineering analysis, coupled with practical design courage, can break the constraints of traditional configurations. Every parameter in a screw gear system is a lever that can be pulled to achieve a specific performance goal. By understanding the complex interdependencies expressed through the formulas and relationships discussed, engineers can tailor screw gear designs for a vast array of modern applications, from precision servo drives to high-duty industrial automation, ensuring that this classic mechanical element continues to evolve and meet new challenges.