In modern gear production, the demand for lightweight and high-performance components has driven the adoption of low-carbon alloy steels formed through stamping processes. These gears often undergo shallow carburizing surface heat treatment to enhance surface hardness while maintaining core toughness. However, improper carburizing parameters can lead to significant heat treatment defects, such as excessive deformation, poor toughness, and inconsistent case depth, which compromise gear reliability and lifespan. As a practitioner in materials engineering, I have observed that controlling these heat treatment defects is critical for achieving precise technical specifications. This article explores the shallow carburizing process for 20Cr2Ni4A steel gears, focusing on optimizing temperature and time to minimize common heat treatment defects like carbon concentration gradients, carbide networking, and dimensional instability. By comparing conventional 910°C carburizing with a lower 860°C approach, we aim to establish a robust methodology that reduces heat treatment defects and ensures consistent quality in small-module, low-load gears.

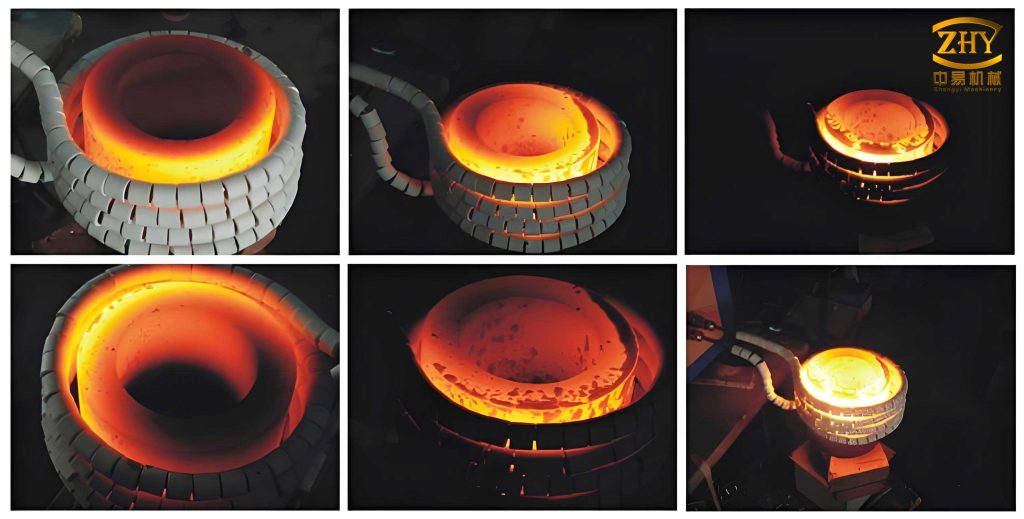

The material under investigation is 20Cr2Ni4A steel, commonly used for gears with a modulus of 3 in low-load applications. The technical requirements include a non-grinding surface carburized layer depth of 0.6–0.8 mm, surface hardness ≥58 HRC, and core hardness of 35–47 HRC. To address potential heat treatment defects, we employed a controlled atmosphere box-type multi-purpose furnace with temperature uniformity of ±5°C and carbon potential uniformity of ±0.02%. The carburizing process was conducted at two temperatures—860°C and 910°C—with varying holding times from 2.5 to 8.5 hours, as outlined in the heat treatment curve. The furnace atmosphere was set to a carbon potential of 1.00% C, followed by quenching and low-temperature tempering to evaluate the impact on heat treatment defects. Microstructural analysis was performed using optical microscopy to assess carburized layer depth and organization, while carbon concentration profiles were determined via layer-by-layer analysis. Hardness measurements were taken using a Vickers hardness tester, with a focus on identifying defects like soft surfaces or excessive brittleness.

The diffusion of carbon atoms during carburizing is governed by Fick’s laws, where the diffusion coefficient (D) plays a key role in determining case depth and uniformity. Temperature significantly influences D, as described by the Arrhenius equation: $$D = D_0 \exp\left(-\frac{Q}{RT}\right)$$ where \(D_0\) is the pre-exponential factor, \(Q\) is the activation energy for diffusion, \(R\) is the gas constant, and \(T\) is the absolute temperature. At higher temperatures, such as 910°C, the diffusion coefficient increases, leading to faster carburizing rates but also elevating the risk of heat treatment defects like excessive case depth and distortion. For shallow carburizing, where the target depth is below 1.0 mm, precise control is essential to avoid heat treatment defects related to over-carburization. The carbon concentration gradient, \(C(x,t)\), can be modeled using the error function solution to Fick’s second law: $$C(x,t) = C_s – (C_s – C_0) \text{erf}\left(\frac{x}{2\sqrt{Dt}}\right)$$ where \(C_s\) is the surface carbon concentration, \(C_0\) is the initial carbon content, \(x\) is the depth, and \(t\) is time. Optimizing \(T\) and \(t\) helps mitigate heat treatment defects by ensuring a gradual gradient that enhances fatigue resistance.

Our experimental results for carburizing speed at different temperatures and times are summarized in Table 1. The data clearly indicate that at 860°C, the increase in case depth is more gradual compared to 910°C, allowing better control over shallow layers and reducing heat treatment defects like short processing windows and uneven hardening. This slower diffusion rate at lower temperatures aligns with the Arrhenius relationship, where a decrease in \(T\) reduces \(D\), thus requiring longer times to achieve the same depth. For instance, to reach approximately 0.7 mm, 860°C requires around 7 hours, whereas 910°C achieves it in about 4.5 hours. This extended time at 860°C enhances process stability, particularly in industrial settings with variable load sizes, thereby minimizing heat treatment defects associated with rapid carburizing, such as distortion and depth inaccuracies.

| Carburizing Time (h) | Case Depth at 860°C (mm) | Case Depth at 910°C (mm) |

|---|---|---|

| 2.5 | 0.46 | 0.54 |

| 3.0 | 0.50 | 0.61 |

| 3.5 | 0.53 | 0.68 |

| 4.0 | 0.57 | 0.73 |

| 4.5 | 0.60 | 0.79 |

| 5.0 | 0.63 | 0.84 |

| 5.5 | 0.66 | 0.89 |

| 6.0 | 0.68 | 0.94 |

| 6.5 | 0.71 | 0.98 |

| 7.0 | 0.74 | 1.03 |

| 7.5 | 0.76 | 1.07 |

| 8.0 | 0.78 | 1.11 |

| 8.5 | 0.80 | 1.15 |

The carbon concentration profiles for both temperatures, as shown in Figure 2 (referenced from data), reveal critical insights into heat treatment defects. At 910°C, the surface carbon content is higher, and the gradient is steeper within the first 0.5 mm, which can lead to heat treatment defects like martensite brittleness and reduced fatigue strength due to abrupt carbon changes. In contrast, the 860°C profile exhibits a more gradual decline in carbon concentration, promoting a smoother transition that enhances toughness and minimizes heat treatment defects related to stress concentration. The surface carbon at both temperatures peaks near 0.1 mm due to decarburization during cooling, a common heat treatment defect that can be mitigated with controlled atmosphere practices. The ideal carbon distribution for shallow carburizing, achieved at 860°C, supports a balance between hardness and ductility, effectively addressing heat treatment defects such as cracking or premature failure.

To quantify the carbon gradient, we can use the following approximation for the case depth (\(d\)) based on diffusion theory: $$d = k\sqrt{Dt}$$ where \(k\) is a constant dependent on carbon potential and material properties. For 20Cr2Ni4A steel, at a carbon potential of 1.00% C, the value of \(k\) varies with temperature, contributing to differences in heat treatment defects. At 860°C, \(D\) is lower, so \(d\) increases slowly, allowing finer control and reducing heat treatment defects like over-depth penetration. This mathematical approach underscores the importance of temperature selection in preventing heat treatment defects associated with shallow case requirements.

Microstructural examination further highlights the impact of temperature on heat treatment defects. Table 2 compares the carbide morphology and retained austenite levels for samples carburized at 860°C and 910°C to a depth of 0.6–0.8 mm, followed by quenching and tempering. At 910°C, carbides show a tendency to form discontinuous networks, a heat treatment defect that can initiate cracks during machining and lower fatigue resistance. In contrast, 860°C produces fine, granular carbides that are uniformly dispersed, mitigating this heat treatment defect and improving wear resistance. Both temperatures yield acceptable levels of martensite and retained austenite, but the superior carbide distribution at 860°C directly addresses heat treatment defects related to brittle phases.

| Sample | Carburizing Temperature (°C) | Case Depth (mm) | Carbide Grade and Morphology | Martensite and Retained Austenite Grade |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 910 | 0.73 | Grade 2–3 (granular with networked tendency) | Grade 1 |

| 2 | 860 | 0.74 | Grade 2 (granular) | Grade 1 |

The micrographs (not shown here due to format restrictions) corroborate these findings, with 910°C samples exhibiting incipient carbide networking, a precursor to heat treatment defects like spalling or reduced toughness. At 860°C, the microstructure is more homogeneous, which helps prevent heat treatment defects during service. This aligns with industry standards where carbide grades 1–3 are acceptable, but minimizing network formation is crucial to avoid heat treatment defects in high-stress applications. The role of tempering after quenching cannot be overlooked, as it relieves stresses and further reduces heat treatment defects such as quench cracking or excessive retained austenite.

Building on these insights, we validated the 860°C shallow carburizing process through production trials with multiple batches of gears. The results, detailed in Table 3, demonstrate consistent performance with minimal heat treatment defects. All batches met the technical specifications for case depth, hardness, and microstructure, while dimensional changes like warpage and size variation were well within limits. This reproducibility underscores the effectiveness of 860°C carburizing in controlling heat treatment defects, making it suitable for mass production where uniformity is paramount. The reduced distortion at lower temperatures is particularly beneficial for precision gears, as it decreases post-machining corrections and associated heat treatment defects from residual stresses.

| Batch | Case Depth (mm) | Surface Hardness (HRC) | Core Hardness (HRC) | Carbide Grade | Martensite and Retained Austenite Grade | Warpage (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.62–0.75 | 59–62 | 35–41 | 2 | 1 | 0.10–0.16 |

| 2 | 0.62–0.73 | 59–62 | 38–43 | 1 | 1 | 0.08–0.12 |

| 3 | 0.61–0.76 | 58–61 | 37–42 | 2 | 1 | 0.12–0.14 |

| 4 | 0.65–0.74 | 59–62 | 42–47 | 3 | 1 | 0.05–0.07 |

The success of this process can be attributed to careful management of heat treatment defects through optimized parameters. For instance, the lower temperature reduces thermal gradients during heating and cooling, which are common sources of heat treatment defects like distortion and residual stresses. Additionally, the slower carburizing rate allows for better carbon potential control, preventing surface decarburization—a subtle heat treatment defect that can compromise hardness. In practice, we recommend using real-time monitoring systems to adjust carbon potential and temperature, further mitigating heat treatment defects in variable load conditions. The relationship between case depth and time can be expressed as: $$t = \frac{d^2}{k^2 D}$$ where adjusting \(T\) to lower \(D\) increases \(t\), providing a larger window for process control and reducing heat treatment defects from timing errors.

Expanding on the theoretical aspects, the activation energy for carbon diffusion in 20Cr2Ni4A steel can be estimated from our data. Using the Arrhenius plot for diffusion coefficients derived from case depth measurements, we calculate \(Q\) to be approximately 140 kJ/mol, which is consistent with alloy steels. This high activation energy implies that temperature changes have a pronounced effect on diffusion, making precise control essential to avoid heat treatment defects. At 860°C, the diffusion coefficient is roughly half that at 910°C, as per the equation: $$\frac{D_{860}}{D_{910}} = \exp\left(-\frac{Q}{R}\left(\frac{1}{1133} – \frac{1}{1183}\right)\right)$$ where temperatures are in Kelvin (860°C = 1133 K, 910°C = 1183 K). This reduction in \(D\) at 860°C directly contributes to fewer heat treatment defects by slowing carbon ingress and allowing more uniform case development.

In industrial applications, heat treatment defects like non-uniform case depth often arise from furnace load variations. Our findings show that 860°C carburizing, with its slower kinetics, is more forgiving to such variations, thereby reducing scrap rates and rework due to heat treatment defects. For example, in a mixed load of gears with different sizes, the extended time at 860°C ensures that all parts reach the target depth simultaneously, minimizing heat treatment defects related to under- or over-carburization. This is particularly important for shallow carburizing, where the margin for error is small, and heat treatment defects can easily lead to rejection. We also observed that at 860°C, the carbon potential of 1.00% C is sufficient to achieve surface hardness without excessive carbon uptake, which can cause heat treatment defects like carbide precipitation or retained austenite instability.

The interplay between microstructure and mechanical properties further emphasizes the need to address heat treatment defects. For 20Cr2Ni4A steel, the core hardness range of 35–47 HRC is achieved through proper tempering, which also mitigates heat treatment defects like temper brittleness. The surface hardness of 58–62 HRC, attained via shallow carburizing, provides wear resistance without compromising toughness, a balance that is often disrupted by heat treatment defects. Our microhardness traverses show a smooth transition from surface to core at 860°C, whereas 910°C exhibits a sharper drop, increasing the risk of heat treatment defects such as delamination or fatigue crack initiation. This can be modeled using a hardness profile function: $$H(x) = H_s – (H_s – H_c) \left(1 – \exp\left(-\alpha x\right)\right)$$ where \(H_s\) is surface hardness, \(H_c\) is core hardness, and \(\alpha\) is a constant influenced by carburizing temperature. Lower \(\alpha\) values at 860°C indicate a gentler gradient, reducing stress concentrations and associated heat treatment defects.

To further contextualize our study, we compare our results with industry standards for shallow carburizing. Typically, temperatures below 900°C are recommended for case depths under 1.0 mm to avoid heat treatment defects like excessive growth and distortion. Our data align with this, showing that 860°C offers a optimal balance between speed and control, effectively minimizing heat treatment defects. In contrast, 910°C, while faster, is prone to heat treatment defects in shallow applications, such as case depth overshoot and reduced process robustness. We attribute this to the exponential nature of diffusion, where small temperature increases can lead to disproportionate changes in depth, exacerbating heat treatment defects. This is captured in the derivative of the case depth equation with respect to temperature: $$\frac{dd}{dT} = \frac{k}{2\sqrt{Dt}} \cdot \frac{dD}{dT}$$ where \(\frac{dD}{dT}\) is positive, indicating that depth sensitivity increases with \(T\), raising the likelihood of heat treatment defects.

In conclusion, our investigation demonstrates that a carburizing temperature of 860°C is superior to 910°C for shallow layer applications in 20Cr2Ni4A steel gears. This approach significantly reduces heat treatment defects, including uncontrolled case depth, carbide networking, and dimensional distortion, while achieving the required hardness and microstructure. The slower diffusion rate at 860°C enhances process controllability, making it ideal for mass production where consistency is key. By integrating theoretical diffusion models with practical validation, we have established a reliable framework for mitigating heat treatment defects in gear manufacturing. Future work could explore advanced techniques like plasma carburizing to further minimize heat treatment defects, but for conventional atmospheres, 860°C stands as a robust solution. Ultimately, addressing heat treatment defects through optimized parameters not only improves gear performance but also extends service life and reduces costs, underscoring the importance of precision in heat treatment practices.