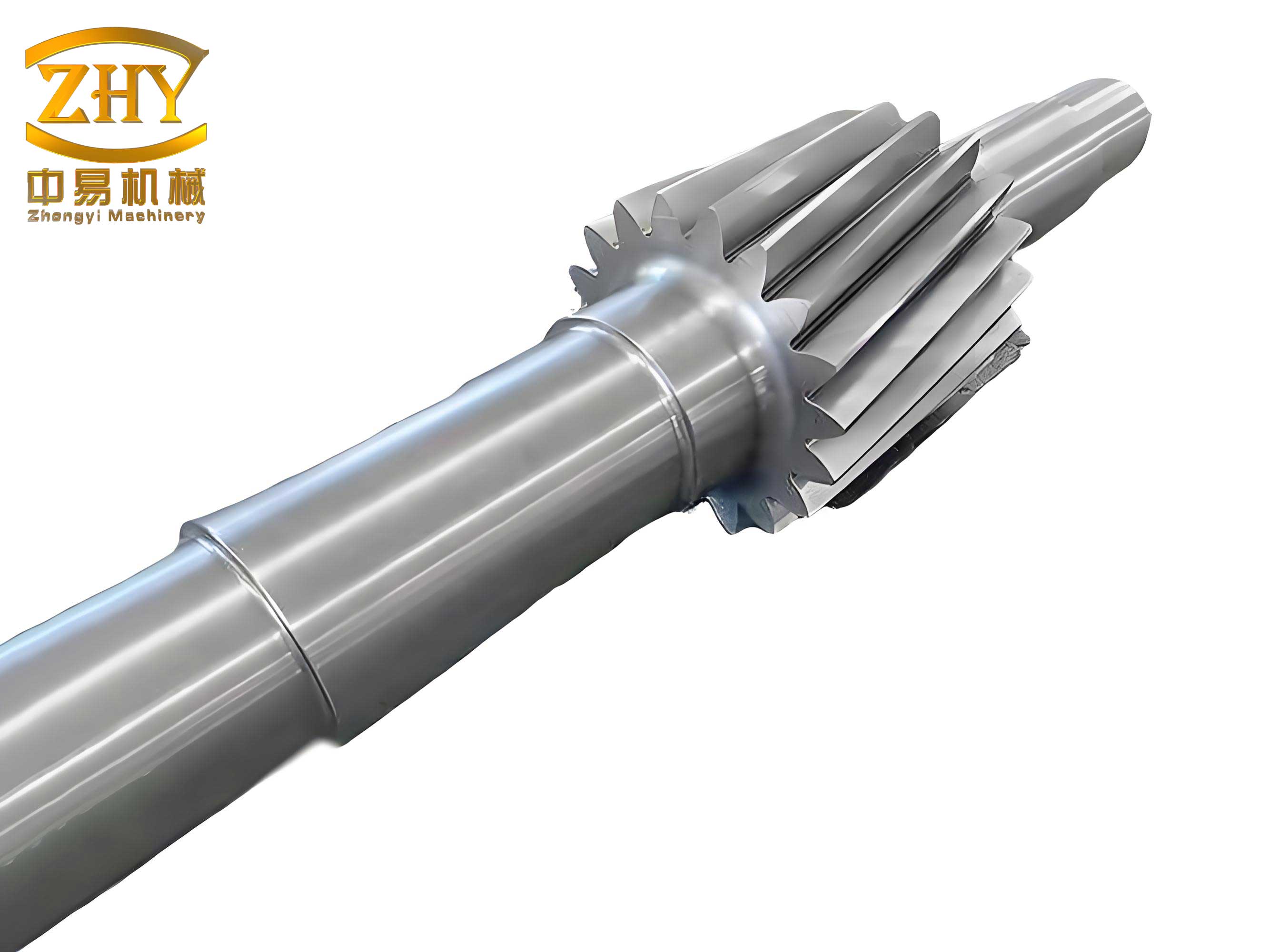

In the evolving landscape of tractor manufacturing, the pursuit of higher efficiency, durability, and performance has become paramount. As a design engineer focused on powertrain systems, I recognize that the main reduction drive gear shafts are critical components that directly influence traction, fuel economy, and overall reliability. These gear shafts transmit torque from the engine to the differential, undergoing significant stresses under varying operational conditions. Therefore, an optimized design methodology is essential to ensure safety, minimize material usage, and extend service life. This article presents a comprehensive auxiliary design approach for tractor main reduction drive gear shafts, integrating computational analysis with practical engineering principles. By leveraging formulas, tables, and modern tools, we can enhance the precision of gear shaft design, ultimately contributing to more robust agricultural machinery.

The design of gear shafts begins with accurately determining the operational torques they must withstand. In tractors, torque can originate from the engine’s rated output or be limited by ground adhesion, depending on the gear ratio and terrain. We consider two primary torque scenarios: one based on the engine’s rated torque, and another derived from the tractor’s adhesion capability. The smaller of these values is selected as the design torque for the gear shafts to prevent overloading and ensure optimal performance.

First, the torque transmitted to the main reduction drive gear shaft from the engine’s rated output is calculated. This involves accounting for the engine’s power, speed, transmission ratio in first gear, and corresponding efficiency. The formula is expressed as:

$$T_1 = \frac{9550 \cdot P \cdot i_1 \cdot \eta_1}{n}$$

where \( T_1 \) is the torque on the gear shaft in N·m, \( P \) is the engine’s rated power in kW, \( n \) is the engine’s rated speed in rpm, \( i_1 \) is the transmission ratio in first gear for the path to the gear shaft, and \( \eta_1 \) is the efficiency of that transmission path. This calculation assumes full engine load, which is common in tractor operations.

Second, the torque limited by ground adhesion is determined to account for scenarios where traction constraints prevent the engine torque from being fully utilized. This is crucial for gear shafts in high-torque, low-speed applications. The formula is:

$$T_2 = \frac{\mu \cdot W \cdot r \cdot i_f \cdot \eta_f}{i_m \cdot \eta_m}$$

where \( T_2 \) is the adhesion-based torque in N·m, \( \mu \) is the coefficient of adhesion between the wheels and ground, \( W \) is the tractor’s adhesive weight in N, \( r \) is the dynamic radius of the drive wheels in m, \( i_f \) is the final drive ratio, \( \eta_f \) is the final drive efficiency, \( i_m \) is the main reduction ratio, and \( \eta_m \) is the main reduction efficiency. This ensures that the gear shafts are not over-designed for conditions where traction is the limiting factor.

The design torque for the gear shafts is then selected as the minimum of these two values to promote safety and efficiency:

$$T_{design} = \min(T_1, T_2)$$

This approach prevents excessive stress on the gear shafts while aligning with real-world operating conditions. To illustrate, Table 1 summarizes the key parameters involved in torque determination for typical tractor gear shafts.

| Symbol | Description | Typical Range | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| \( P \) | Engine rated power | 50-150 | kW |

| \( n \) | Engine rated speed | 2000-2500 | rpm |

| \( i_1 \) | First gear transmission ratio | 3-6 | – |

| \( \eta_1 \) | Transmission efficiency | 0.85-0.95 | – |

| \( \mu \) | Adhesion coefficient | 0.4-0.6 | – |

| \( W \) | Adhesive weight | 20000-50000 | N |

| \( r \) | Drive wheel dynamic radius | 0.5-0.8 | m |

| \( i_f \) | Final drive ratio | 4-8 | – |

| \( \eta_f \) | Final drive efficiency | 0.90-0.95 | – |

| \( i_m \) | Main reduction ratio | 2-5 | – |

| \( \eta_m \) | Main reduction efficiency | 0.92-0.96 | – |

Once the design torque is established, the next step involves assessing the strength of the gear shafts, focusing on both the gears and the shaft itself. The gear shafts comprise the active bevel gears that mesh to transmit torque, and their integrity is vital for preventing failures. We evaluate two primary strength criteria: bending strength and contact strength. These calculations ensure that the gear shafts can endure cyclic loads and surface pressures without yielding or pitting.

For bending strength, the stress at the root of the gear teeth must not exceed the allowable material stress. The formula for bending stress in bevel gears, particularly for the active gear on the shaft, is given by:

$$\sigma_F = \frac{T_{design} \cdot K_A \cdot K_V \cdot K_m}{m^3 \cdot Z \cdot J} \leq [\sigma_F]$$

where \( \sigma_F \) is the bending stress in MPa, \( m \) is the module at the large end of the gear in mm, \( Z \) is the number of teeth on the active gear, \( J \) is the bending strength geometry factor (dimensionless), \( K_A \) is the overload factor (typically 1.0-1.5 for tractors), \( K_V \) is the dynamic factor (accounting for vibrations, often 1.0-1.3), and \( K_m \) is the load distribution factor. The load distribution factor depends on the support configuration of the gear shafts: for simply supported gear shafts, \( K_m = 1.0-1.2 \), while for cantilevered gear shafts, \( K_m = 1.2-1.5 \). The allowable bending stress \( [\sigma_F] \) is derived from material properties, such as case-hardened steels commonly used in gear shafts.

The geometry factor \( J \) is critical and varies with gear type (straight or spiral bevel) and tooth geometry. For straight bevel gears, \( J \) can be approximated from standard charts based on the number of teeth and shaft angle; for spiral bevel gears, it incorporates helix angle effects. Table 2 provides typical values of \( J \) for common gear shaft configurations, aiding in quick design iterations.

| Gear Type | Number of Teeth \( Z \) | Shaft Angle | \( J \) Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Straight Bevel | 10-20 | 90° | 0.20-0.30 |

| Straight Bevel | 21-30 | 90° | 0.25-0.35 |

| Spiral Bevel | 10-20 | 90° | 0.30-0.40 |

| Spiral Bevel | 21-30 | 90° | 0.35-0.45 |

For contact strength, the Hertzian stress at the gear mesh must be controlled to prevent surface fatigue. The contact stress formula for bevel gears on gear shafts is:

$$\sigma_H = Z_E \sqrt{\frac{T_{design} \cdot K_A \cdot K_V \cdot K_m}{b \cdot d_m^2} \cdot \frac{i_g + 1}{i_g}} \leq [\sigma_H]$$

where \( \sigma_H \) is the contact stress in MPa, \( Z_E \) is the elasticity coefficient in \( \sqrt{\text{MPa}} \), \( b \) is the face width of the gear in mm, \( d_m \) is the mean pitch diameter of the active gear in mm, and \( i_g \) is the gear ratio of the mating pair. The elasticity coefficient depends on material properties: for steel gears, \( Z_E = 189.8 \sqrt{\text{MPa}} \). The allowable contact stress \( [\sigma_H] \) is based on material endurance limits, often enhanced by heat treatment. The mean pitch diameter \( d_m \) is calculated from the gear geometry: \( d_m = d – b \sin \gamma \), where \( d \) is the large-end pitch diameter and \( \gamma \) is the pitch cone angle. This ensures accurate stress evaluation for gear shafts with conical shapes.

To streamline these calculations, we can use computational aids. For instance, the geometry factors for bending and contact strength can be derived from empirical formulas or lookup tables, reducing manual errors. In our design process for gear shafts, we often employ software to interpolate these factors based on gear parameters, ensuring precision. Additionally, the load distribution factor \( K_m \) is refined through finite element analysis, especially for complex gear shaft assemblies where support stiffness varies.

After verifying the gear strength, we focus on the shaft portion of the gear shafts. The shaft must resist torsional stresses induced by the design torque, as well as bending moments from gear forces. The torsional stress is a key criterion, calculated as:

$$\tau_t = \frac{T_{design} \cdot K_t}{W_t} \leq [\tau]$$

where \( \tau_t \) is the torsional stress in MPa, \( K_t \) is the stress concentration factor (typically 1.5-2.5 for keyways or splines on gear shafts), \( W_t \) is the torsional section modulus in mm³, and \( [\tau] \) is the allowable shear stress for the shaft material. For solid circular shafts, \( W_t = \frac{\pi d^3}{16} \), but for gear shafts with splined sections, an equivalent diameter is used based on the mean of major and minor diameters. This accounts for stress risers common in gear shafts.

The gear forces on the shaft include tangential, radial, and axial components, which contribute to bending stresses. The tangential force \( F_t \) is derived from the design torque and mean pitch diameter:

$$F_t = \frac{2 T_{design}}{d_m}$$

This force, along with others, generates bending moments that must be analyzed through shaft layout diagrams. For gear shafts supported by bearings, we calculate reactions and plot bending moment diagrams to identify critical sections. The combined stress state, using von Mises criterion, ensures the shaft’s yield margin. In practice, gear shafts are often designed with safety factors of 2.0 or higher for dynamic loads.

To facilitate these computations, we use auxiliary design tools such as spreadsheets or custom software. These tools integrate all formulas, material databases, and geometry inputs, allowing rapid iteration for gear shafts. For example, Table 3 summarizes typical material properties for gear shafts, enabling quick selection during design.

| Material | Yield Strength (MPa) | Ultimate Strength (MPa) | Allowable Bending Stress \( [\sigma_F] \) (MPa) | Allowable Contact Stress \( [\sigma_H] \) (MPa) | Allowable Shear Stress \( [\tau] \) (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case-Hardened Steel AISI 8620 | 450 | 750 | 250-300 | 1200-1500 | 150-200 |

| Through-Hardened Steel AISI 4140 | 600 | 850 | 300-350 | 1000-1300 | 180-220 |

| Alloy Steel AISI 4340 | 700 | 950 | 350-400 | 1300-1600 | 200-250 |

In addition to static strength, gear shafts must endure fatigue loads due to cyclic torque variations. We perform fatigue analysis using modified Goodman diagrams, incorporating mean and alternating stresses. The fatigue strength reduction factors for gear shafts, especially at splines or fillets, are considered to predict life cycles. This is crucial for tractors operating in harsh environments where gear shafts face frequent shock loads.

The design process for gear shafts also involves optimization for weight and cost. By varying parameters like module, face width, and shaft diameter, we can achieve a balance between strength and material usage. Multi-objective optimization algorithms, implemented in software, help identify Pareto-optimal solutions for gear shafts. For instance, reducing shaft diameter may increase stress but lower weight, so we trade off based on application requirements.

To validate our methodology, we applied it to a case study for a mid-sized tractor’s main reduction drive gear shafts. Input parameters included: \( P = 75 \text{ kW} \), \( n = 2200 \text{ rpm} \), \( i_1 = 4.5 \), \( \eta_1 = 0.92 \), \( \mu = 0.5 \), \( W = 30000 \text{ N} \), \( r = 0.6 \text{ m} \), \( i_f = 6.0 \), \( \eta_f = 0.93 \), \( i_m = 3.2 \), \( \eta_m = 0.94 \). Using the torque formulas, we computed \( T_1 = 1350 \text{ N·m} \) and \( T_2 = 1250 \text{ N·m} \), so \( T_{design} = 1250 \text{ N·m} \). For the active bevel gear on the gear shafts, we selected a spiral bevel with \( Z = 15 \), \( m = 6 \text{ mm} \), \( b = 40 \text{ mm} \), and \( J = 0.35 \) from Table 2. The bending stress was \( \sigma_F = 280 \text{ MPa} \), below the allowable \( 300 \text{ MPa} \) for AISI 8620 steel. Contact stress was \( \sigma_H = 1100 \text{ MPa} \), within the allowable \( 1300 \text{ MPa} \). The shaft diameter was set at 50 mm with splines, yielding torsional stress \( \tau_t = 160 \text{ MPa} \), safe against \( 180 \text{ MPa} \). This confirmed the robustness of our gear shafts design.

Furthermore, we explored sensitivity analyses to understand how variations in adhesion or engine power affect gear shafts. For example, if adhesion coefficient drops to 0.3 due to muddy conditions, \( T_2 \) decreases, reducing the design torque and potentially allowing lighter gear shafts. This insight informs adaptive design strategies for different tractor models.

The integration of computer-aided design (CAD) and finite element analysis (FEA) has revolutionized gear shafts development. We create 3D models of gear shafts, simulate meshing forces, and optimize geometries for stress distribution. This virtual prototyping reduces physical testing costs and accelerates time-to-market. Additionally, we use algorithms to automate the selection of standard components like bearings and seals for gear shafts assemblies, ensuring compatibility.

In conclusion, the auxiliary design of tractor main reduction drive gear shafts is a multifaceted process that balances torque determination, strength verification, and optimization. By employing formulas, tables, and computational tools, we can achieve precise, reliable designs that enhance tractor performance. This methodology not only ensures safety and durability but also promotes material efficiency, contributing to sustainable agriculture. Future advancements may include real-time monitoring of gear shafts loads via sensors, enabling predictive maintenance and further optimization. As gear shafts continue to be pivotal in powertrains, our design approaches will evolve to meet the demands of next-generation machinery.

Throughout this discussion, the term “gear shafts” has been emphasized to underscore their centrality in tractor systems. From torque calculations to fatigue analysis, every aspect of design revolves around ensuring these components perform flawlessly under diverse conditions. By adhering to the principles outlined here, engineers can develop gear shafts that meet rigorous standards while pushing the boundaries of innovation.