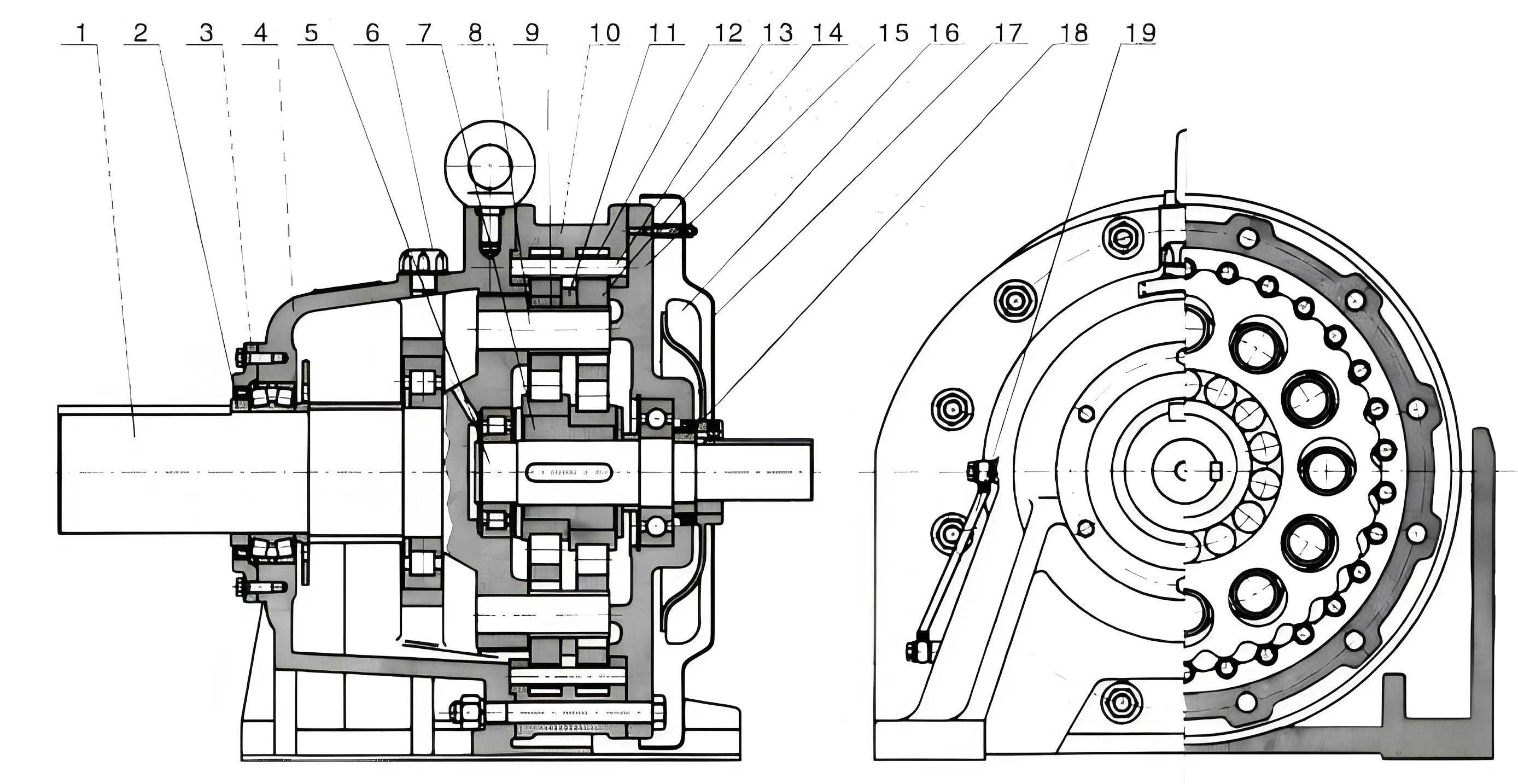

In my extensive experience with precision power transmission systems, the cycloidal drive stands out as a marvel of engineering, offering high reduction ratios, exceptional torque density, and remarkable durability within a compact footprint. Its unique principle of operation, based on the meshing of a cycloidal disc with stationary pins, provides a smooth, low-backlash motion that is ideal for many industrial processes. However, a critical challenge emerges when these drives are deployed in vertical reactor or mixer applications, such as those found in chemical, pharmaceutical, and food processing industries. The standard cycloidal drive is fundamentally designed to transmit pure torque. When subjected to significant axial loads—forces parallel to the axis of rotation—its internal components, particularly the bearings, experience accelerated wear and a drastic reduction in operational efficiency and service life. This article, drawn from firsthand engineering practice, delves into the core of this issue and presents several effective, field-proven solutions for axial load management, ensuring that the cycloidal drive can fulfill its potential even in the most demanding vertical stirring setups.

The heart of the problem lies in the nature of vertical搅拌 applications. A stirring impeller submerged in a fluid, especially a viscous or crystallizing medium, generates substantial hydrodynamic forces. During processes like polymerization or crystallization, the fluid’s viscosity can increase exponentially, and the impeller may encounter uneven resistance, leading to significant downward or upward axial thrust. This axial force, denoted as \( F_a \), is an uninvited guest for a standard cycloidal drive unit. The primary bearings within the cycloidal drive, which are typically sized for radial loads and modest axial components from internal preload, are suddenly burdened with this external \( F_a \). The consequence is a severe impact on the predicted bearing life. The basic rating life for a bearing, often expressed as the \( L_{10} \) life (the number of revolutions at which 90% of a group of identical bearings will survive), is calculated using the formula:

$$ L_{10} = \left( \frac{C}{P} \right)^p \times 10^6 \text{ revolutions} $$

Here, \( C \) is the dynamic load rating (a property of the bearing), \( P \) is the equivalent dynamic bearing load, and \( p \) is an exponent (3 for ball bearings, 10/3 for roller bearings). For a combined radial and axial load, \( P \) is calculated as \( P = XF_r + YF_a \), where \( F_r \) is the radial load, and \( X \) and \( Y \) are factors. A large \( F_a \) drastically increases \( P \), causing the life \( L_{10} \) to plummet inversely with the cube (or 10/3 power) of the load increase. Therefore, to protect the integrity of the cycloidal drive and its bearings, this axial force must be diverted or “unloaded” from the drive’s internal structure entirely. Over the years, my team and I have developed and refined several pragmatic schemes to achieve this, which I will detail below.

Fundamental Principles and Axial Force Estimation

Before exploring the solutions, it is crucial to quantify the adversary—the axial load. The axial force on a stirrer shaft is not a constant; it varies with process conditions. It can be estimated through hydrodynamic principles. For a simple disc turbine impeller, a simplified model for the maximum axial thrust during normal operation can be derived from pressure differentials:

$$ F_{a,\text{hyd}} \approx K \cdot \rho \cdot N^2 \cdot D^4 $$

Where \( \rho \) is the fluid density, \( N \) is the impeller rotational speed, \( D \) is the impeller diameter, and \( K \) is a thrust coefficient dependent on impeller geometry. However, the most severe loading often occurs during transient phases like start-up in a settled slurry or when the product begins to crystallize. During crystallization, the medium can transform from a Newtonian fluid to a non-Newtonian, highly viscous paste. The resistance torque and axial thrust can spike dramatically. An empirical correction factor \( \beta \) (often ranging from 2 to 10 based on material) can be applied:

$$ F_{a,\text{max}} = \beta \cdot F_{a,\text{hyd}} + F_{\text{shaft weight}} $$

This \( F_{a,\text{max}} \) is the design load for any axial unloading device. The goal of all subsequent schemes is to ensure this force is carried by a dedicated structure, bypassing the cycloidal drive’s main housing and bearings.

Scheme 1: Integrated Thrust Bearing and Sealed Chamber Assembly

The first and most robust approach involves integrating a dedicated thrust bearing assembly directly above or below the cycloidal drive unit, housed within a sealed chamber. This method physically intercepts the axial load from the stirrer shaft before it can enter the cycloidal drive. In this configuration, the output shaft of the cycloidal drive is coupled to the stirrer shaft via a flexible coupling that transmits torque but is axially “soft” (like a bellows or disc coupling), or it is designed as a quill shaft that allows limited axial float. The thrust is then carried by a set of angular contact ball bearings or a spherical roller thrust bearing mounted in a separate housing. This assembly is often sealed with a mechanical seal or a pack of gland packing to contain the process medium, providing resistance against heat and corrosion—a critical requirement in reactor environments.

The sizing of this thrust bearing is paramount. We use the following calculation sequence. First, the required basic dynamic load rating \( C_{\text{req}} \) for the thrust bearing is determined based on the desired life \( L_{10h} \) in operating hours:

$$ C_{\text{req}} = P_{\text{eq}} \cdot \left( \frac{L_{10h} \cdot n \cdot 60}{10^6} \right)^{1/p} $$

where \( n \) is the rotational speed in RPM, and \( P_{\text{eq}} = F_{a,\text{max}} \) for pure thrust bearings. For a paired arrangement of angular contact bearings in a back-to-back (DB) configuration, the preload and stiffness can be optimized using formulas that account for axial deflection \( \delta_a \):

$$ \delta_a = \frac{F_a^{2/3}}{K} $$

where \( K \) is a stiffness constant dependent on the bearing type and preload. This scheme effectively isolates the cycloidal drive from axial forces, allowing it to operate under its ideal pure-torque condition. The efficiency of the cycloidal drive, often above 90% for single-stage units, remains uncompromised. The trade-off is increased mechanical complexity and length of the overall drive train.

Scheme 2: Dual-Support (Statically Determinate) Shaft Design

The second scheme addresses not only axial load but also the lateral stability of the long, slender stirrer shaft. A standard setup with the cycloidal drive as the sole upper support can lead to excessive deflection, run-out, and vibration, especially at critical speeds. This scheme introduces a second support point—typically a radial bearing—located near the bottom of the reactor vessel. The cycloidal drive’s output shaft is extended downward to form the stirrer shaft, and this shaft is supported at two points: at the drive output (bearing set A) and at a lower guide bearing (bearing set B). This creates a statically determinate beam, effectively eliminating shaft whip and instability.

To manage the axial load, a key feature is incorporated: one of these support points is axially fixed, while the other is free to float axially. Commonly, the upper support within the cycloidal drive housing (or an added thrust bearing adjacent to it) is designed as the axial fixed point, carrying the entire \( F_a \). The lower guide bearing is a plain bush or radial roller bearing housed in a cartridge that allows axial slip. This arrangement ensures thermal expansion of the shaft does not create parasitic axial loads. The reaction forces at the bearings can be calculated using simple statics for a vertically oriented shaft:

$$ R_A + R_B = F_{\text{shaft weight}} $$

$$ M_A = F_a \cdot L + F_{\text{shaft weight}} \cdot \frac{L}{2} $$

Where \( R_A \) and \( R_B \) are radial reactions, \( M_A \) is the moment at the top support, and \( L \) is the distance between supports. The axial force \( F_a \) is fully resolved at support A. This dual-support design profoundly reduces dynamic loads and wear on mechanical seals and the cycloidal drive components, thereby extending the system’s overall lifespan. It is particularly advantageous for deep tanks and high-speed stirring applications.

Scheme 3: Hydraulic Auto-Balancing with Minimal Mechanical Intervention

The third scheme is an elegant solution that minimizes added mechanical components by leveraging the process fluid itself. In this design, the stirrer shaft is connected rigidly or semi-rigidly to the output of the cycloidal drive. However, at the very bottom of the shaft, near the impeller, there is no traditional lower bearing. Instead, a simple, large-clearance bushing or sleeve—fabricated from a highly corrosion-resistant material like stainless steel, Hastelloy, or even ceramic—provides only initial radial location during start-up and shutdown. The genius of this scheme lies in its operational principle.

When the impeller rotates in the fluid, it generates a localized flow field. Under ideal conditions, the hydrodynamic forces around a properly designed impeller can create a near-perfect radial centering effect and a partial axial balance. For axial balance, consider the pressure distribution on the upper and lower surfaces of the impeller. By slightly tailoring the impeller blade angles (e.g., using a pitched-blade turbine), one can induce a net upward hydraulic force that counteracts a portion of the downward weight and process-induced thrust. The system seeks an equilibrium point. The axial equilibrium can be described by a force balance:

$$ F_{a,\text{hyd, up}} + F_{\text{bearing friction}} = F_{a,\text{process, down}} + W_{\text{shaft/impeller}} $$

Where \( F_{a,\text{hyd, up}} \) is the fluid-derived uplift. The clearance sleeve acts only as a safety limiter for radial excursion. Consequently, during steady-state operation, the stirrer shaft “floats” on a cushion of fluid, auto-centering itself and imposing minimal residual axial load on the cycloidal drive’s bearings. This scheme offers remarkable simplicity, reduced maintenance (no lower bearing to fail or lubricate), and excellent corrosion resistance. Its performance is highly dependent on fluid properties and impeller geometry, making it best suited for applications with relatively consistent process media.

Comparative Analysis and Selection Guidelines

Choosing the right axial load management scheme for a cycloidal drive in a vertical reactor depends on multiple factors: the magnitude and variability of the axial load, process media characteristics, required maintenance access, and cost considerations. The following table synthesizes the key attributes of the three schemes:

| Feature / Scheme | Scheme 1: Integrated Thrust Bearing | Scheme 2: Dual-Support Shaft | Scheme 3: Hydraulic Auto-Balancing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Mechanism | Mechanical interception via dedicated thrust bearing. | Structural load path via statically determinate beam. | Hydrodynamic force balance in process fluid. |

| Axial Load on Cycloidal Drive | Nearly zero (fully unloaded). | Fully carried at fixed upper point (drive is part of fixed point). | Minimized, variable, dependent on operation. |

| Shaft Stability | Depends on coupling/shaft design; may require lower guide. | Excellent (two-point support). | Good under operation; limited during start/stop. |

| Mechanical Complexity | High (added bearing housing, seals). | Moderate to High (requires lower bearing penetration). | Very Low (only a sleeve). |

| Maintenance Requirement | Moderate (thrust bearing and seal maintenance). | Moderate (two bearing points to service). | Very Low (sleeve is durable, no moving parts). |

| Corrosion Resistance | Good (materials can be selected for housing/seal). | Challenge at lower bearing seal. | Excellent (sleeve material can be highly inert). |

| Process Dependency | Low. Works universally. | Low. Works universally. | High. Sensitive to fluid viscosity & density changes. |

| Ideal Application | High & variable axial loads, harsh/corrosive environments. | Deep tanks, high speeds, where shaft stiffness is critical. | Consistent fluid processes, where simplicity is paramount. |

| Relative Cost | High | Medium-High | Low |

Beyond this qualitative comparison, a quantitative decision matrix can be used. Assigning weight factors \( w_i \) (e.g., Load Capacity=0.3, Cost=0.2, Maintenance=0.25, Corrosion=0.25) and scoring each scheme \( s_{ij} \) on a scale of 1-10 for each criterion \( j \), the total score \( T_i \) for scheme \( i \) is:

$$ T_i = \sum_{j=1}^{n} w_j \cdot s_{ij} $$

This engineering judgment, combined with the specific application data, guides the optimal selection.

Deep Dive: Cycloidal Drive Torque Transmission and System Integration

To fully appreciate the importance of axial unloading, one must understand the torque-handling prowess of the cycloidal drive. The output torque \( T_{\text{out}} \) is related to the input torque \( T_{\text{in}} \) by the reduction ratio \( i \) and the mechanical efficiency \( \eta \):

$$ T_{\text{out}} = T_{\text{in}} \cdot i \cdot \eta $$

A typical single-stage cycloidal drive can achieve ratios \( i \) from about 6:1 to 119:1 with \( \eta \) often between 0.85 and 0.95. The torque is transmitted through the rolling action of the cycloidal disc(s) against the pin housing. This action generates primarily radial forces on the disc’s bearing. Introducing a large external axial force misaligns this delicate internal force equilibrium, increasing friction and hysteresis losses. The efficiency can drop significantly, and the internal bearing life, calculated earlier, becomes the system’s weak link. Therefore, protecting the cycloidal drive from axial load isn’t a luxury; it’s a necessity for reliable, long-term operation.

When integrating any unloading scheme, the system’s torsional stiffness must also be considered, especially for processes requiring precise speed control. The overall torsional stiffness \( K_{\text{tot}} \) from motor to impeller is a series combination of the stiffness of the motor coupling, the cycloidal drive itself \( K_{cd} \), the unloading coupling (if present), and the shaft \( K_{\text{shaft}} \):

$$ \frac{1}{K_{\text{tot}}} = \frac{1}{K_{\text{coupling1}}} + \frac{1}{K_{cd}} + \frac{1}{K_{\text{unload coupling}}} + \frac{1}{K_{\text{shaft}}} $$

A high \( K_{\text{tot}} \) is desirable to minimize torsional vibration. Schemes 1 and 3, which might use flexible couplings for axial decoupling, can reduce \( K_{\text{tot}} \) if not carefully selected. Scheme 2, with a rigid or semi-rigid connection, typically preserves higher torsional stiffness.

Application-Specific Adaptations Across Industries

The versatility of the cycloidal drive, when paired with an appropriate axial unloading strategy, opens doors to numerous industries. In each sector, the specific process demands fine-tune the scheme selection.

Chemical & Petrochemical: Reactors often handle aggressive, high-temperature media. Scheme 1 (Integrated Thrust Bearing) is frequently preferred. The thrust bearing housing can be jacketed for cooling, and the seals are chosen from advanced materials like perfluoroelastomers. The robust design handles sudden load changes during catalyst injection or exothermic reactions. The reliability of the cycloidal drive in such a protected setup is paramount for continuous, safe operation.

Pharmaceutical & Biotechnology: Here, cleanliness, sanitization, and containment are critical. Scheme 3 (Hydraulic Auto-Balancing) gains traction for simple mixing tasks with non-viscous buffers or media. The absence of a lower bearing eliminates a dead leg or crevice where product could accumulate. For more viscous bio-fermentations, Scheme 2 with a clean-in-place (CIP) capable lower bearing housing might be specified. The compactness of the cycloidal drive helps in maintaining a streamlined reactor headplate.

Food & Beverage: Similar hygiene requirements apply. For large-scale crystallization in sugar refining or salt production, where axial loads can become enormous, Scheme 1 or a heavy-duty variant of Scheme 2 is essential. The cycloidal drive’s ability to provide high torque at low output speeds is ideal for slowly stirring thick, crystallizing masses.

Water & Wastewater Treatment: Large flocculation and sedimentation tanks use long vertical shafts. Scheme 2 is almost standard here, providing the necessary shaft stability over great lengths. The cycloidal drive, mounted on the bridge, is relieved of bending moments, and the axial thrust from large-diameter propellers is carried by a dedicated thrust bearing within the drive’s support structure.

In every case, the core principle remains: safeguard the cycloidal drive from axial loading to unlock its full service life and performance.

Maintenance Philosophy and Lifecycle Considerations

Implementing an axial unloading system transforms the maintenance paradigm. The cycloidal drive itself becomes a relatively low-maintenance component, primarily requiring periodic lubrication (oil change for lubricated versions) and condition monitoring (vibration, temperature). The maintenance focus shifts to the unloading device. For Scheme 1, the thrust bearing and its seal are the primary wear items. Bearing life can be re-estimated using the modified \( L_{10h} \) formula with the actual measured \( F_a \). For Scheme 2, both the upper and lower bearings need monitoring. The lower seal, in particular, is exposed to the process and may require more frequent attention.

A significant advantage of these designs is modularity. Should the thrust assembly in Scheme 1 fail, it can often be repaired or replaced without dismantling the entire cycloidal drive or the reactor internals. This modularity reduces downtime—a critical economic factor. Furthermore, by ensuring the cycloidal drive operates within its design envelope, the mean time between failures (MTBF) for the entire drive system increases substantially. The total cost of ownership (TCO) is lowered, even if the initial capital expenditure (CAPEX) for Schemes 1 or 2 is higher than a non-unloaded setup.

In conclusion, the application of a cycloidal drive in a vertical reactor stirrer is a classic example of an excellent component requiring a supportive system to shine. The inherent axial load from the stirring process is a formidable challenge that, if ignored, will lead to premature failure and operational inefficiency. Through the three principal schemes detailed here—the integrated thrust bearing, the dual-support shaft, and the hydraulic auto-balancing method—engineers have a powerful toolkit to address this challenge. Each scheme offers a different balance of performance, complexity, and cost, allowing for tailored solutions across the chemical, pharmaceutical, food, and water treatment industries. By conscientiously implementing such axial load management, we not only protect the investment in the cycloidal drive but also ensure the reliability, efficiency, and longevity of the entire mixing process. The cycloidal drive, thus unshackled from unintended loads, can truly deliver on its promise of robust, precise, and durable power transmission.