In my extensive experience as a mechanical design engineer, I have consistently found that the integration of three-dimensional (3D) modeling software with two-dimensional (2D) drafting tools significantly enhances the efficiency and accuracy of product development. This is particularly true for complex assemblies such as a screw gear reducer, where precise geometric relationships and detailed manufacturing drawings are paramount. The screw gear, often referred to in the context of worm gear sets, is a critical component in many mechanical transmission systems due to its high reduction ratio and compact design. In this article, I will elaborate on a comprehensive methodology for the parametric design of a screw gear reducer, leveraging the strengths of SolidWorks for 3D parametric modeling and assembly simulation, and AutoCAD for the refinement and production of 2D engineering drawings. This approach not only streamlines the design process but also ensures that the final output meets rigorous industrial standards. Throughout this discussion, the term ‘screw gear’ will be emphasized to underscore its centrality in this design paradigm.

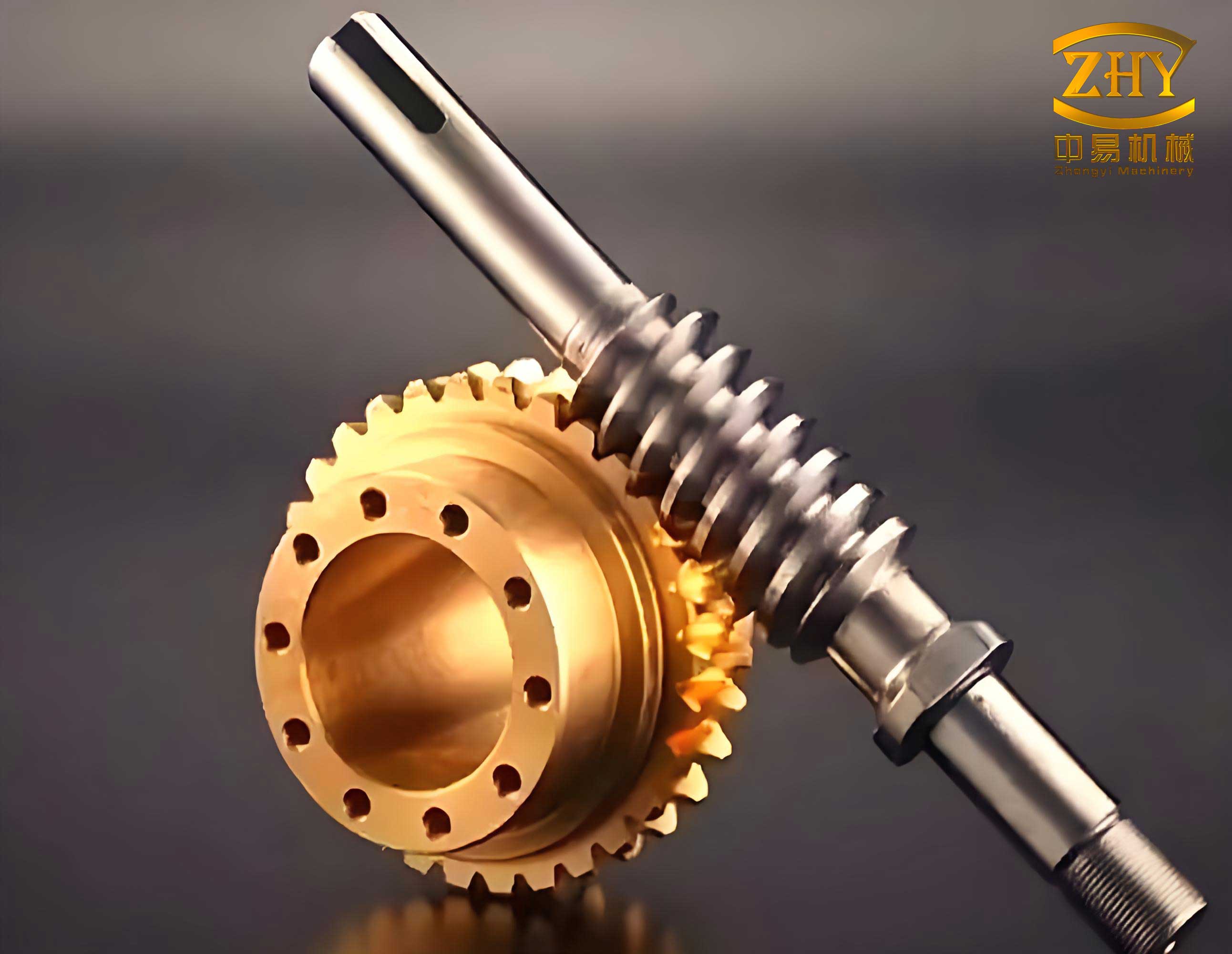

The advent of parametric design has revolutionized mechanical engineering by allowing designers to create models with dimensions and features that are driven by mathematical relationships and constraints. This means that any change to a primary parameter, such as the module or number of teeth in a screw gear, automatically propagates through the entire model, updating all dependent geometries. Such capability is invaluable when designing a screw gear reducer, as it involves numerous interrelated components like the worm (screw), worm wheel, housing, bearings, and shafts. My workflow begins in SolidWorks, a robust 3D CAD environment known for its user-friendly interface and powerful feature-based modeling tools. The goal is to construct a fully parametric digital prototype of the screw gear reducer, which can be easily modified for different design variants or performance requirements.

To initiate the design, I first conduct a thorough structural analysis of the screw gear reducer. This involves defining key performance parameters such as the reduction ratio, input torque, output speed, and center distance. For a screw gear set, the fundamental geometric parameters are interrelated through specific formulas. The axial module \( m_a \) of the worm and the transverse module \( m_t \) of the worm wheel are critical. Their relationship in a standard 90° shaft angle configuration is given by:

$$ m_a = m_t \cdot \cos(\gamma) $$

where \( \gamma \) is the lead angle of the worm. The lead \( L \) of the worm, which is the axial distance the worm thread advances in one complete turn, is calculated as:

$$ L = \pi \cdot d_w \cdot \tan(\gamma) = \pi \cdot m_a \cdot z_1 $$

Here, \( d_w \) is the pitch diameter of the worm, and \( z_1 \) is the number of starts (threads) on the worm. For the worm wheel (the gear meshing with the screw), the number of teeth \( z_2 \) is related to the reduction ratio \( i \) by:

$$ i = \frac{z_2}{z_1} $$

These formulas form the backbone of the parametric model. In SolidWorks, I create global variables and equations to capture these relationships. For instance, I define a variable for the module and then link the diameters, tooth profiles, and clearances to this variable. This ensures that changing the module instantly updates all related dimensions in the screw gear components.

The actual modeling of the screw gear components follows a systematic feature-based approach. For the worm (the screw gear’s driving element), I typically start with a sketch of its pitch cylinder. Using the ‘Helix and Spiral’ feature, I generate a helical path based on the calculated lead. The tooth profile, which is often an involute shape but adapted for worm gears, is then swept along this helix to create the thread. The exact profile can be defined using parametric equations. For a standard involute profile for the worm wheel tooth, the coordinates of the involute curve in parametric form are:

$$ x = r_b (\cos(\theta) + \theta \sin(\theta)) $$

$$ y = r_b (\sin(\theta) – \theta \cos(\theta)) $$

where \( r_b \) is the base radius and \( \theta \) is the involute angle. In practice, for screw gears, modifications like throat diameter and face width are crucial. I create these features using SolidWorks’ extrusion, cut, and fillet commands. The table below summarizes the primary parameters and their typical values or formulas for a generic screw gear set used in a reducer design. This table serves as a quick reference and can be embedded as a design specification sheet.

| Parameter | Symbol | Formula / Typical Value | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Center Distance | \( a \) | \( a = \frac{d_1 + d_2}{2} \) | Driven by housing constraints |

| Worm Pitch Diameter | \( d_1 \) | \( d_1 \approx \frac{z_1 \cdot m_a}{\tan(\gamma)} \) | Often standardized |

| Worm Wheel Pitch Diameter | \( d_2 \) | \( d_2 = m_t \cdot z_2 \) | Determines output torque capacity |

| Axial Module | \( m_a \) | Selected from standard series (e.g., 2, 2.5, 3) | Primary design variable for screw gear size |

| Number of Worm Starts | \( z_1 \) | 1, 2, 4 (common) | Affects reduction ratio and efficiency |

| Number of Worm Wheel Teeth | \( z_2 \) | \( z_2 = i \cdot z_1 \) | Typically > 30 for smooth engagement |

| Lead Angle | \( \gamma \) | \( \gamma = \arctan\left(\frac{z_1 \cdot m_a}{d_1}\right) \) | Critical for self-locking and efficiency |

| Face Width of Worm Wheel | \( b \) | \( b \approx 0.73 \cdot d_1 \) (empirical) | Ensures sufficient contact area |

Once the worm and worm wheel—the core screw gear pair—are modeled, I proceed to create the housing components: the upper and lower casings. These are designed parametrically with features like bolt holes, bearing seats, and oil seals, all linked to the screw gear dimensions. For example, the bore for the worm shaft bearing is sized based on the worm’s root diameter plus necessary clearances. I use SolidWorks’ design tables or configurations to manage different sizes of the screw gear reducer within the same model file. This parametric flexibility is a significant advantage when catering to custom client requirements.

After all individual parts of the screw gear reducer are created, the next phase is virtual assembly. In SolidWorks, I create a new assembly document and insert the lower housing as the fixed base component. This mirrors the actual assembly process. I then insert the worm (screw gear shaft) and the worm wheel, aligning them using standard mates such as concentric and coincident constraints. To accurately simulate the meshing of the screw gear pair, I apply a mechanical mate specifically designed for gears. In SolidWorks, this is achieved through the ‘Gear Mate’ feature, where I select the cylindrical faces or reference circles representing the pitch diameters of the worm and worm wheel. I define the gear ratio as the inverse of the reduction ratio \( i \). This mate ensures that rotational motion of the worm causes proportional rotation of the worm wheel, allowing for dynamic motion studies. I can then run simulations to check for interferences, measure angular velocities, and verify the range of motion. This virtual prototyping is crucial for identifying design flaws before physical manufacturing.

To aid in assembly understanding and to create documentation for maintenance, I often generate an exploded view of the screw gear reducer assembly. SolidWorks provides tools to create exploded steps by dragging components along axes. I systematically explode the assembly to show the sequence of part installation: from bearings and seals on the worm shaft, to the worm wheel onto its shaft, and finally the upper housing fastened with bolts. This exploded view, along with bill of materials (BOM), becomes an integral part of the technical documentation package. The ability to visualize the assembly disassembled reinforces the spatial relationships between components, especially how the screw gear meshes within the confined housing.

The transition from 3D model to 2D production drawings is a critical step. While SolidWorks has a competent drawing module capable of generating orthographic views, sections, and details, I have found that for final drawing refinement and adherence to specific company drafting standards, AutoCAD remains unparalleled. Therefore, my process involves generating the initial drawing views in SolidWorks. I create drawing sheets with front, top, side, and isometric views of the screw gear reducer assembly as well as detailed part drawings for each component, focusing particularly on the screw gear elements. I also include section views to reveal internal features like the tooth engagement area and oil passages. Dimensions are added parametrically, meaning they are linked to the 3D model. However, for complex annotations, tolerance stacking, and certain types of geometric dimensioning and tolerancing (GD&T), I prefer the granular control offered by AutoCAD.

I export these drawing sheets from SolidWorks in the DWG format, which is natively supported by AutoCAD. Upon opening the DWG file in AutoCAD, I embark on a detailed editing and enhancement process. This typically involves several steps: First, I audit the layers. SolidWorks exports geometry on many layers; I consolidate and rename layers according to our internal standards (e.g., ‘OBJECT’ for visible edges, ‘HIDDEN’ for hidden lines, ‘DIM’ for dimensions). Second, I scrutinize line types and line weights. I ensure that visible outlines are thick, hidden lines are dashed, and center lines are appropriately styled. Third, and most importantly, I refine the dimensioning and annotation. For the screw gear components, this includes adding specific callouts for gear data. For example, next to the worm wheel drawing, I might add a table with parameters:

| Gear Data | Value |

|---|---|

| Module (Transverse) | 3 mm |

| Number of Teeth | 40 |

| Pressure Angle | 20° |

| Helix Hand | Right |

| Material | Bronze (SAE 65) |

I also add precise geometric tolerances for features like the worm shaft’s bearing journals and the worm wheel’s bore. Surface finish symbols are placed on critical mating surfaces. The power of AutoCAD’s text editing, block creation, and dimension style management allows me to produce a polished, professional drawing that leaves no ambiguity for the machine shop. Furthermore, I often add notes regarding assembly procedures, lubrication specifications, and inspection criteria specific to the screw gear set. This hybrid approach—leveraging SolidWorks for intelligent view generation and AutoCAD for detailed drafting—combines the best of both worlds: associativity with the 3D model and drafting excellence.

To illustrate the practical benefits, let me delve deeper into the parametric aspects of the screw gear itself. The efficiency \( \eta \) of a screw gear drive is a key performance metric and is highly dependent on the lead angle \( \gamma \) and the coefficient of friction \( \mu \). It can be estimated using the following formula:

$$ \eta = \frac{\tan(\gamma)}{\tan(\gamma + \phi)} $$

where \( \phi = \arctan(\mu) \) is the friction angle. This relationship is crucial for optimizing the screw gear design. In my parametric SolidWorks model, I can create a design study that varies the lead angle and observes its effect on the efficiency and overall size of the reducer. By driving the worm geometry with an equation that includes efficiency targets, I ensure the design is not just geometrically correct but also performance-optimized. This level of integration is difficult to achieve in a non-parametric or purely 2D environment.

Another advanced application is the use of configurations for product families. Suppose we need to design a series of screw gear reducers with center distances ranging from 100 mm to 250 mm. Instead of creating separate models, I create one master model with all features driven by global variables. I then define configurations in SolidWorks, each with a different set of values for the primary variables like center distance \( a \) and module \( m_a \). The software automatically regenerates all parts and assemblies for each configuration. The table below shows a subset of such a product family for the screw gear reducer.

| Model Code | Center Distance (mm) | Axial Module (mm) | Reduction Ratio (i) | Rated Torque (Nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SGR-100 | 100 | 2.0 | 20:1 | 150 |

| SGR-150 | 150 | 2.5 | 30:1 | 400 |

| SGR-200 | 200 | 3.0 | 40:1 | 800 |

| SGR-250 | 250 | 4.0 | 50:1 | 1500 |

For each configuration, the 3D model updates, and subsequently, the drawing views in the associated SolidWorks drawings update as well. When exported to AutoCAD, I can batch process these DWG files using scripts to apply standard layers and title blocks, further accelerating the drawing production for the entire screw gear reducer series.

In terms of design validation, the screw gear meshing condition requires careful attention to the contact pattern. While physical prototyping is ultimate, SolidWorks’ simulation capabilities, such as static stress analysis, can be applied to the screw gear components to ensure they can withstand the operational loads. For instance, the bending stress \( \sigma_b \) at the root of the worm wheel tooth can be approximated using the Lewis formula modified for helical gears:

$$ \sigma_b = \frac{F_t}{b \cdot m_t \cdot Y} \cdot K_a \cdot K_v \cdot K_m $$

where \( F_t \) is the tangential force, \( b \) is the face width, \( Y \) is the Lewis form factor, and \( K_a \), \( K_v \), \( K_m \) are application, velocity, and load distribution factors, respectively. By linking the results of such calculations back to the parametric dimensions (e.g., increasing face width \( b \) if stress is too high), I create a closed-loop design system that is both intelligent and responsive.

The integration does not stop at geometry. With SolidWorks, I can also generate rendered images and animations of the screw gear reducer in operation, which are invaluable for marketing and customer presentations. These visuals clearly demonstrate the interaction of the screw gear pair, showing how rotation is transferred from the high-speed worm to the low-speed worm wheel. When combined with the precise manufacturing drawings from AutoCAD, the design package becomes comprehensive, serving the needs of engineers, machinists, and sales teams alike.

Reflecting on this methodology, the synergy between SolidWorks and AutoCAD for screw gear reducer design offers profound advantages. Firstly, it drastically reduces the design cycle time. Changes made to the 3D parametric model automatically update the core geometry in the drawings, minimizing manual rework. Secondly, it enhances accuracy. The 3D model eliminates guesswork in spatial relationships, especially for complex components like the screw gear, where clearances and alignments are critical. Thirdly, it improves communication. The 3D models and animations help stakeholders visualize the product, while the standardized 2D drawings from AutoCAD ensure unambiguous fabrication and assembly instructions. Finally, this approach facilitates innovation. By easily exploring different screw gear parameters (lead angle, module, number of starts) through parametric changes, I can quickly iterate and optimize the design for weight, cost, or performance.

In conclusion, the parametric design of a screw gear reducer using SolidWorks and AutoCAD represents a mature and highly effective workflow in modern mechanical design. By harnessing the parametric and associative modeling power of SolidWorks for the creation of the screw gear and its housing, and then employing the superior drafting and detailing capabilities of AutoCAD for final drawing production, I achieve a seamless bridge from conceptual design to manufacturable documentation. This hybrid strategy not only capitalizes on the strengths of each software but also aligns with the practical habits and standards prevalent in the industry. As screw gear reducers continue to be vital in applications ranging from conveyor systems to robotic actuators, mastering this integrated design approach is essential for any engineer aiming to deliver high-quality, reliable mechanical power transmission solutions efficiently. The repeated focus on the screw gear throughout the process—from initial parameter calculation to final drawing annotation—ensures that this critical component receives the detailed attention it warrants, resulting in a robust and optimized reducer design.