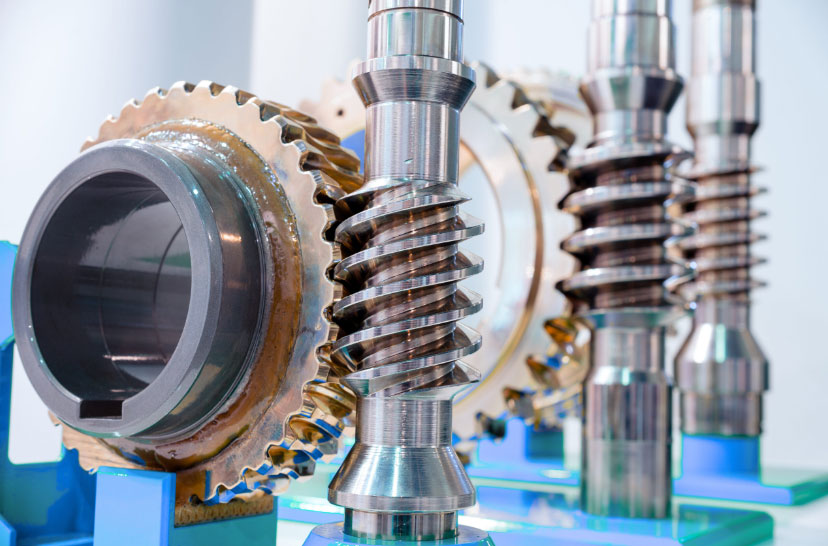

In the field of aviation, the Auxiliary Power Unit (APU) plays a critical role in providing independent compressed air, electrical power, and emergency energy to enhance aircraft safety. The worm gears used in APU air passage hatch cover actuators are core transmission components characterized by their compact size and high load-bearing capacity. The reliability of these worm gears is paramount for the normal operation of the APU. To ensure their performance, this study investigates the parametric modeling and simulation analysis of worm gears for aviation APU applications. The research focuses on developing accurate parametric modeling methods, performing contact stress simulations, analyzing temperature distributions, and evaluating dynamic characteristics. The findings aim to provide a foundation for improving the design and reliability of worm gears in APU systems.

The tooth surface of the worm gear in APU systems is an irregular curved surface, and existing modeling methods often fail to ensure high precision. This study proposes a novel parametric modeling approach based on the spatial meshing principle of worm gears. By deriving parametric expressions for the tooth profile on the middle plane and parallel planes of the worm gear, the tooth surface is generated using profile curves as baselines through a cutting method. For the worm, the tooth surface is obtained by rotating a cutting tool profile to remove material. This method enables parametric, programmable, and high-precision modeling of worm gears for APU applications.

Using VB.net language, a parametric modeling plugin for APU worm gears is developed. The plugin facilitates data interaction with databases and 3D modeling software, enabling the automatic generation of 3D models based on specified parameters. The correctness of the generated models is verified through interference checks and motion transmission simulations. Various worm gear assemblies with different numbers of threads are analyzed to ensure proper meshing and movement.

Finite element simulations are conducted to analyze the contact stress between the worm and worm gear during the opening and locking of the APU air passage hatch cover under different wind conditions. The strength of the worm shaft is also evaluated. Comparisons with theoretical calculations show that conventional steel-copper (20CrMnTi-ZCuSn10Pb1) worm gear pairs do not meet contact strength requirements, whereas a new steel-steel (20CrMnTi-0Cr17Ni4Cu4Nb) pair satisfies the criteria. The effects of assembly errors, external disturbances on the worm shaft, and lightweight treatments on contact stress are investigated. Data fitting methods, including function fitting and BP neural networks, are employed to model the relationship between assembly errors and contact stress.

For the new steel-steel worm gear material pair, the temperature distribution on the tooth surface during hatch cover operation is analyzed. Experimental measurements of the friction coefficient between material specimens are performed. The body temperature field of the worm gear is established, and the flash temperature during meshing is derived using Blok’s theory. The maximum temperature during meshing is found to be below the failure temperature of the lubricating grease. Modal analysis of the worm gear and shaft reveals that their natural frequencies are significantly higher than the excitation frequencies, ensuring stable operation. This comprehensive analysis validates the operational reliability of APU worm gears from multiple perspectives.

The spatial meshing principle of worm gears is fundamental to analyzing their kinematics, dynamics, and tooth contact. To derive the tooth profile expressions for the worm gear, coordinate systems are established for the cutting tool edge, worm machining, and worm gear meshing. Based on coordinate transformation principles, transformation matrices between these systems are derived. The worm gear tooth surface equations are obtained from the meshing conditions and manufacturing principles. For the APU worm gear, the tooth surface is generated by a trapezoidal straight-edge cutting tool on a lathe, resulting in an Archimedean spiral surface. The parametric equations for the worm gear tooth profile on the middle plane and parallel planes are derived as follows.

The coordinate system for the cutting tool edge is defined with the z-axis aligned with the worm’s rotation axis. The parametric equation for the left cutting edge is given by:

$$x_k = l \cos \alpha_k, \quad y_k = 0, \quad z_k = -l \sin \alpha_k$$

where \( l \) is the distance from a point on the cutting edge to the origin, and \( \alpha_k \) is the tool profile angle. The transformation from the cutting tool coordinate system to the worm coordinate system involves rotation and translation, leading to the worm helix surface equation:

$$x_1 = l \cos \alpha_k \cos \theta, \quad y_1 = l \cos \alpha_k \sin \theta, \quad z_1 = -l \sin \alpha_k + p\theta$$

where \( \theta \) is the rotation angle, and \( p \) is the spiral parameter. The normal vector on the worm tooth surface is derived from the partial derivatives of the surface equation. The meshing condition between the worm and worm gear requires that the relative velocity vector is perpendicular to the normal vector at the contact point. This leads to the meshing equation:

$$n \cdot v_{12} = 0$$

where \( n \) is the normal vector, and \( v_{12} \) is the relative velocity. By solving the meshing equation along with the worm surface equations, the contact lines on the worm are obtained. Transforming these to the worm gear coordinate system yields the worm gear tooth surface equations. Applying boundary conditions, such as fixing the z-coordinate, gives the parametric expressions for the tooth profile on parallel planes. For example, on the middle plane, the closed tooth profile curve includes the meshing portion and corrected non-meshing parts, such as the root and tip circles.

The parametric modeling method for the worm involves simulating the machining process using a trapezoidal cutting tool. The worm blank is created by extruding a circle representing the tip diameter. The cutting tool profile is sketched on the front plane, with dimensions based on the worm parameters, such as module and pressure angle. A helix with a lead equal to the worm’s lead is created, and the tool profile is swept along this helix to cut the worm teeth. For multi-start worms, the cut is circularly patterned. The worm shaft is then extended on both sides. This process is parameterized by linking the tool and blank dimensions to input parameters.

For the worm gear, the irregular tooth surface is generated by slicing the gear with planes parallel to the middle plane. On each plane, the tooth profile curve is drawn based on the derived parametric expressions. These curves are used as baselines to loft and cut the worm gear blank, forming the tooth surface. The non-meshing parts of the profile are corrected to ensure a closed curve. The worm gear body, including the hub and spokes, is modeled separately. The entire process is controlled by parameters such as module, number of teeth, and gear width, allowing for rapid model generation.

The modeling plugin is developed using VB.net in Visual Studio, with SolidWorks as the 3D modeling platform and an Access database for storing standard parameters. The plugin interface includes input fields for structural parameters, such as module, worm pitch diameter, number of starts, and gear teeth. The database provides standard values from mechanical design handbooks, ensuring compliance with industry norms. The plugin calculates derived parameters, such as transmission ratio and center distance, in real-time. Error checking prevents invalid inputs, such as non-integer tooth counts. Buttons trigger the automatic generation of worm and worm gear models, including simplified versions for analysis.

The plugin control program handles parameter declaration, database interaction, input validation, data updating, parameter assignment, SolidWorks interaction, and model creation. Key API functions from SolidWorks are used to perform operations like sketching, extruding, and patterning. For example, creating a helix involves the InsertHelix method, while cutting uses InsertCutSwept4. The program ensures that models are generated accurately and efficiently.

To validate the models, interference checks are performed in SolidWorks, confirming no collisions occur. Motion simulations in ADAMS analyze the transmission behavior. For a worm gear with 30 teeth and worms with 1, 2, and 4 starts, the output angular velocity of the gear remains stable at the theoretical value, demonstrating correct meshing. In contrast, models from existing plugins like Geartrax show significant fluctuations. For the APU worm gear with 27 teeth and a single-start worm, the transmission ratio is constant at 27, verifying the model’s accuracy.

Finite element analysis in ANSYS Workbench evaluates the contact stress and worm shaft strength during hatch cover operation. The worm gear assembly is imported, and materials are defined, such as steel for the worm and both steel and copper for the gear. The mesh is refined in the contact region, and contact parameters are set with friction. Loads and boundary conditions are applied based on operational scenarios, including wind loads. For example, under strong wind conditions, the worm rotates at 810 RPM, and the gear torque is set to the maximum value. The analysis covers one full rotation of the worm, with results showing the contact stress variation.

The contact stress results for different wind levels and materials are summarized in the table below. The maximum contact stress occurs during locking under strong wind, with steel worm gears experiencing higher stress than copper ones. The steel-steel pair meets the allowable stress, while the steel-copper pair does not.

| Condition | Steel Worm Gear Max Stress (MPa) | Copper Worm Gear Max Stress (MPa) |

|---|---|---|

| Inlet Drive (4-level wind) | 1113.36 | 982.63 |

| Inlet Lock (4-level wind) | 1420.46 | 1257.79 |

| Exhaust Drive (4-level wind) | 927.84 | 810.29 |

| Exhaust Lock (4-level wind) | 994.05 | 852.77 |

The theoretical contact stress is calculated using Hertzian theory:

$$\sigma_H = Z_E \sqrt{\frac{F_n}{L \rho_{\Sigma}}}$$

where \( Z_E \) is the elasticity factor, \( F_n \) is the normal load, \( L \) is the contact length, and \( \rho_{\Sigma} \) is the composite curvature radius. The finite element results are within 8% of theoretical values for driving and 5% for locking, validating the simulation.

The effect of lightweight treatment on the worm shaft is analyzed by hollowing the shaft center. As the hollow diameter increases, the contact stress changes slightly, but the shaft stress may spike beyond a certain diameter. For example, in inlet drive, a hollow diameter over 4 mm causes a sudden increase in shaft stress. External disturbances on the worm shaft in different directions alter the contact stress; upward and forward disturbances reduce stress, while downward and backward disturbances increase it.

Assembly errors, including center distance error, axial offset error, and shaft angle error, are studied. The center distance error increases contact stress, while axial offset and shaft angle errors cause non-monotonic changes. Data fitting with BP neural networks accurately models the relationship between shaft angle error and contact stress, outperforming polynomial and Fourier fits.

The friction coefficient between the steel-steel material pair is measured experimentally using a ball-on-disk setup. The test machine applies loads corresponding to contact stresses, and friction data is collected via sensors and data acquisition systems. The average friction coefficient ranges from 0.105 to 0.118 under different loads and lubricants. Among various greases, synthetic oil with lithium complex base performs best, with the lowest friction coefficient.

The temperature analysis includes the body temperature and flash temperature of the worm gear. The body temperature field is solved using the heat conduction equation with boundary conditions for convection and heat flux. The convective heat transfer coefficients for different tooth surfaces are calculated based on equivalent geometries. For example, the gear end face is treated as a rotating disk, and the meshing face uses a correlation for flow over a surface. The heat flux from friction is given by:

$$q = \beta \alpha f P_n v_s$$

where \( \beta \) is the heat partition coefficient, \( \alpha \) is the energy conversion factor, \( f \) is the friction coefficient, \( P_n \) is the contact pressure, and \( v_s \) is the sliding velocity. The average heat flux is derived considering the meshing cycle.

The body temperature distribution shows the highest temperature on the meshing surface, with inlet drive reaching 36.844°C and exhaust drive 34.344°C. The flash temperature during meshing is calculated using Blok’s theory, resulting in 60.71°C for inlet and 55.19°C for exhaust. The total temperature is below the grease failure temperature of 180°C, ensuring proper lubrication.

Modal analysis of the worm gear and shaft determines the natural frequencies. The first ten frequencies range from 637.23 Hz to 7225.5 Hz, which are much higher than the excitation frequencies (50-300 Hz), preventing resonance. The mode shapes include bending and torsional vibrations, with the lowest frequency corresponding to shaft bending.

In conclusion, this research develops a parametric modeling method for APU worm gears, validated through interference checks and motion simulations. Finite element analysis confirms that steel-steel worm gear pairs meet contact strength requirements, while steel-copper pairs do not. Temperature and modal analyses ensure operational reliability under various conditions. The plugin and methods provide a foundation for efficient design and analysis of worm gears in aviation applications.