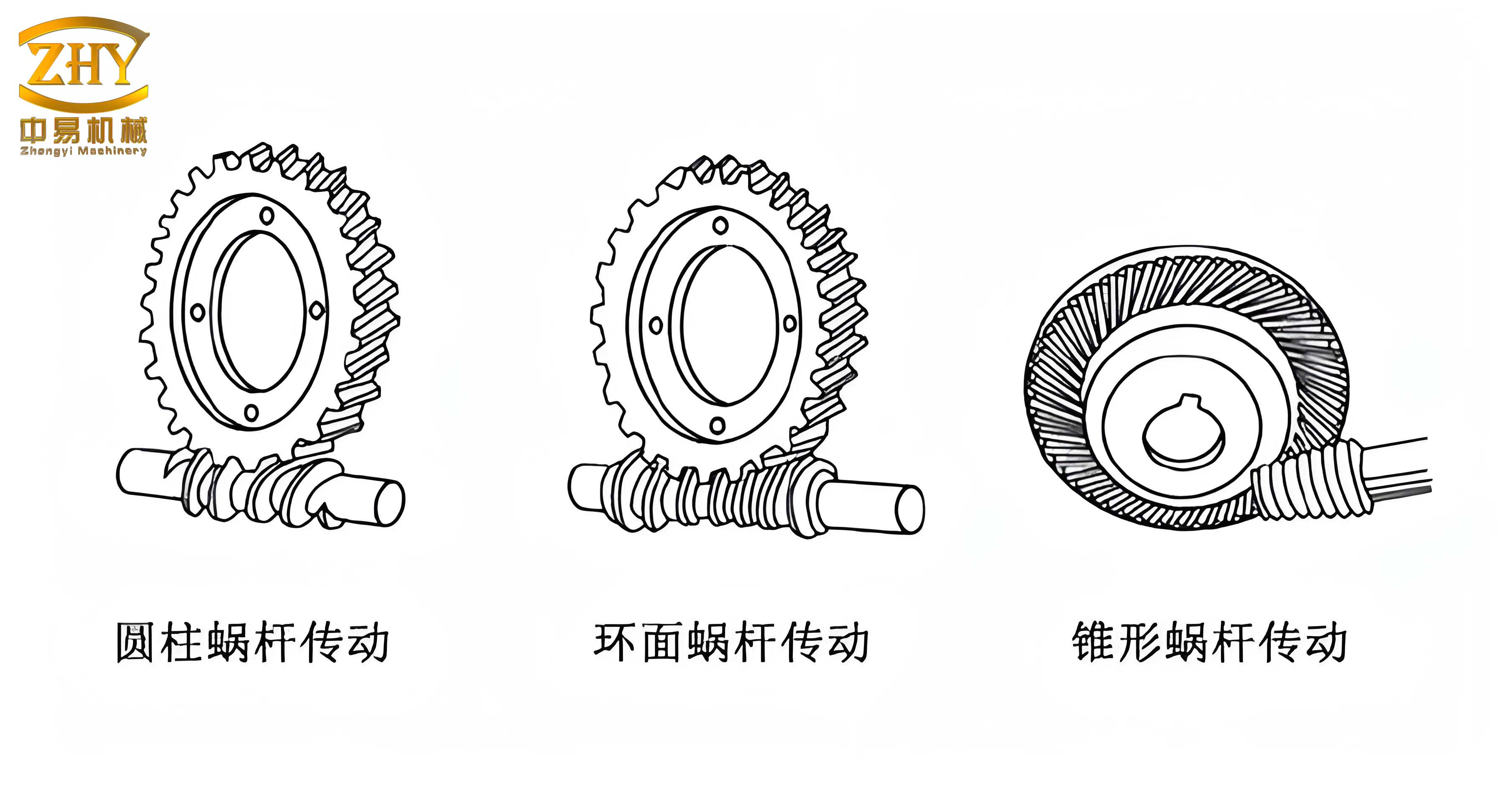

As an engineer deeply involved in computer-aided design and manufacturing, I have extensively used UGNX, a powerful CAD/CAE/CAM integrated software developed by EDS. This software is renowned for its robust parametric design capabilities, which are essential in modern design and manufacturing industries. By combining parametric modeling and feature-based modeling philosophies, UGNX allows for dimension-driven or variable design methods to define and manipulate features. Its prowess in complex surface modeling and intricate shape creation is unparalleled, making it a preferred tool for advanced mechanical design tasks. In this article, I will delve into the parametric modeling of screw gears, a type of gearing system that includes worm and worm gear assemblies, highlighting how UGNX facilitates this process through tools like “Law Curves,” “Expressions,” and “Dynamic WCS.” Screw gears are critical components in many machines due to their compact structure, high transmission ratios, smooth operation, and self-locking properties under certain conditions. They are widely used in machine tools, automotive systems, instruments, lifting equipment, and metallurgical machinery. However, their complex tooth profiles pose challenges for direct 3D solid modeling in common CAD/CAM software. UGNX overcomes this by enabling the creation of sophisticated tooth curves, though its learning curve can be steep for those unfamiliar with its environment. Here, I will share my experience in modeling an Archimedean screw gear set parametrically, which can serve as a reference for other complex 3D parametric modeling projects.

Screw gears, often referred to as worm gears, are derived from crossed helical gear systems. The worm, akin to a screw, features teeth that wrap around its pitch cylinder multiple times, while the worm gear has a concave shape to partially envelop the worm, ensuring line contact for efficient power transmission. This design mimics screw-nut mechanisms, where the worm acts as the screw and the worm gear as the nut. From a geometric perspective, the worm is a shaft-like component with segments, teeth, keyways, chamfers, and undercuts, whereas the worm gear is a disk-like part with a rotary body, teeth, holes, ribs, and keyways. Understanding these characteristics is crucial for effective parametric modeling in UGNX, as it allows us to break down the design into manageable features driven by parameters such as module, pressure angle, and lead angle. The parametric approach ensures that any design changes propagate automatically, saving time and reducing errors. In the following sections, I will detail the step-by-step modeling process for both the worm and worm gear, incorporating tables and formulas to summarize key aspects. Throughout, I will emphasize the importance of screw gears in mechanical systems and how UGNX tools streamline their creation.

Geometric Analysis of Screw Gears

Before diving into modeling, it’s essential to analyze the geometric features of screw gears. These gears operate on principles of helical motion, where the worm’s spiral teeth engage with the worm gear’s curved teeth. The primary parameters include axial module, number of teeth, pressure angle, lead angle, and pitch diameters. For an Archimedean screw gear, the worm has a trapezoidal tooth profile in the axial plane, while the worm gear tooth profile is generated based on the worm’s geometry. The interaction involves complex kinematics, which UGNX can simulate through parametric relationships. I often start by defining these parameters in a table to organize the design data. For instance, consider the following parameters for an example screw gear set:

| Parameter | Symbol | Worm Value | Worm Gear Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Axial Module | $m_a$ | 2 mm | – |

| Normal Module | $m_n$ | – | 2 mm |

| Number of Teeth | $z$ | 1 | 27 |

| Pressure Angle | $\alpha$ | 20° | 20° |

| Lead Angle | $\gamma$ | 4°23’55” | 4°23’55” |

| Pitch Diameter | $d$ | 26 mm | 54 mm |

| Tip Diameter | $d_a$ | 30 mm | 62 mm |

| Root Diameter | $d_f$ | 21 mm | 49 mm |

| Center Distance | $a$ | 40 mm | 40 mm |

These parameters drive the entire modeling process. The worm’s geometry is based on its axial cross-section, which can be represented using equations. For example, the lead of the worm is given by $L = \pi m_a z_1$, where $z_1$ is the worm’s number of teeth. The lead angle $\gamma$ relates to the pitch diameter $d_1$ and lead $L$ as $\tan \gamma = L / (\pi d_1)$. In UGNX, such formulas are implemented using expressions to ensure parametric control. Similarly, the worm gear’s tooth profile involves an involute curve, derived from its base circle. The parametric equations for an involute are: $$x = r_b (\cos \epsilon + \epsilon \sin \epsilon)$$ $$y = r_b (\sin \epsilon – \epsilon \cos \epsilon)$$ where $r_b$ is the base circle radius, calculated as $r_b = \frac{m_n z_2 \cos \alpha}{2}$, and $\epsilon$ is the roll angle. By leveraging UGNX’s expression tool, these equations can be input to generate precise curves. This geometric foundation is vital for creating accurate screw gears that meet functional requirements.

Parametric Modeling Process for Screw Gears in UGNX

In UGNX, parametric modeling revolves around feature-based operations where dimensions and relationships are defined through sketches, expressions, and constraints. I will now outline the process for modeling both the worm and worm gear, emphasizing how each step ties back to the parameters. This approach not only ensures accuracy but also allows for easy modifications—a key benefit of screw gears in adaptive design systems.

Worm Modeling

The worm, being a shaft-like component, starts with creating a blank or base body. I typically use the sketch function in UGNX to draw a 2D profile of the worm’s axial cross-section. This sketch is fully parametric, meaning dimensions like diameters and lengths are driven by the parameters in the table. For instance, the sketch includes circles representing the tip, pitch, and root diameters. After sketching, I apply the “Revolve” command to generate a 3D solid, followed by “Chamfer” operations to add necessary features. This results in the worm base body, which serves as the foundation for adding teeth.

Next, I create the tooth space profile. Using the “Dynamic WCS” tool, I adjust the work coordinate system so that the ZC axis aligns with the lead angle $\gamma$. This ensures that the tooth space sketch plane is perpendicular to the worm’s helix. The sketch consists of a trapezoidal shape defined by the pressure angle $\alpha = 20°$, with dimensions linked to the tip and root radii. For example, the width at the tip is set to the tip radius plus a small offset (e.g., 0.1 mm) to facilitate Boolean operations later. This parametric sketch is then used to generate the cutting tool for the teeth.

To form the helical tooth spaces, I draw a helix as the guide curve. In UGNX, this is done via “Insert → Curve → Helix,” where the helix radius is set to the pitch radius $r_1 = d_1/2 = 13$ mm, and the pitch is derived from the lead $L$. The number of turns can be adjusted based on the worm’s length. With the helix and tooth space sketch ready, I use the “Sweep” command to create a helical solid that represents the material to be removed. This solid acts as a tool body in a Boolean “Subtract” operation, where the worm base body is the target. The result is a worm with precise helical teeth. Additional features like fillets and keyways are added using “Blend” and “Slot” functions, completing the worm model. Throughout this process, I rely on parametric links—for example, the helix parameters are tied to the module and lead angle via expressions, ensuring that any change in these screw gears parameters updates the entire model automatically.

Worm Gear Modeling

The worm gear modeling is more intricate due to its concave shape and involute teeth. I begin by creating the gear blank using the “Cylinder” command for the main body, followed by “Extrude” and “Subtract” to form the central hole and keyway. A spherical groove is then added to partially envelop the worm, using the “Groove” function with parameters derived from the center distance and throat diameter. For the example set, the groove radius is $a – r_{throat} = 11$ mm, where $r_{throat}$ is half the throat diameter. This step ensures proper engagement between the screw gears.

The core of worm gear modeling lies in generating the involute tooth profile. As mentioned earlier, the involute equations are implemented in UGNX using the “Law Curve” tool. First, I define expressions in “Tools → Expressions.” For the given parameters, the expressions include: $$m = 2$$ $$\alpha = 20$$ $$z = 27$$ $$r_b = m \times z \times \cos(\alpha) / 2$$ $$t = 0.001$$ $$\epsilon = t \times 45$$ $$x_t = r_b \times \cos(\epsilon) + r_b \times \epsilon \times \sin(\epsilon)$$ $$y_t = r_b \times \sin(\epsilon) – r_b \times \epsilon \times \cos(\epsilon)$$ $$z_t = 0$$ Here, $t$ is a variable that controls the point position on the involute, and $\epsilon$ is the roll angle in radians. The “Law Curve” function uses these to plot the involute, which is then incorporated into a sketch. In the sketch, I draw circles for the tip, pitch, and root diameters, and place the involute curve relative to them. Using “Offset Curve” and “Mirror Curve” commands, I create a full tooth profile, which is trimmed and prepared for sweeping.

This tooth profile sketch is then rotated by the lead angle $\gamma$ to align with the worm gear’s orientation. A helix is generated similar to the worm, but with parameters adjusted for the worm gear’s pitch. Using “Sweep,” I produce a helical solid that represents one tooth space. To replicate this for all teeth, I use “Edit → Transform → Copy,” rotating the solid by $360/z_2$ degrees for each copy. Finally, a Boolean “Subtract” operation removes these solids from the worm gear blank, resulting in a fully detailed worm gear. This parametric method ensures that the tooth spacing and profile are accurate, which is critical for the smooth operation of screw gears in transmission systems.

Advanced Parametric Techniques for Screw Gears

Beyond basic modeling, UGNX offers advanced tools for enhancing the design of screw gears. For instance, I often use “User-Defined Features” (UDFs) to encapsulate the worm or worm gear modeling steps into reusable components. This is particularly useful for standard screw gears series, where parameters vary but the overall process remains similar. By creating a UDF with input parameters like module, pressure angle, and number of teeth, I can quickly generate new screw gears designs without repeating steps. Additionally, the “Assembly” environment in UGNX allows for kinematic simulation of screw gears pairs. After modeling both components, I assemble them with appropriate constraints, such as aligning axes and setting contact conditions. This enables interference checking and dynamic collision detection, ensuring that the screw gears mesh properly without clashes.

To further optimize screw gears, I integrate finite element analysis (FEA) within UGNX. Using the “Simulation” module, I apply loads and boundary conditions to evaluate stress distribution and deformation. The parametric links ensure that any design change automatically updates the FEA model, facilitating iterative improvement. For example, if the pressure angle is modified to reduce wear in screw gears, the entire model and analysis adjust accordingly. Tables summarizing performance metrics can be created, such as:

| Parameter | Value | Effect on Screw Gears |

|---|---|---|

| Module Increase | From 2 mm to 2.5 mm | Higher load capacity but larger size |

| Pressure Angle Increase | From 20° to 25° | Improved tooth strength but higher friction |

| Lead Angle Decrease | From 5° to 4° | Reduced efficiency but better self-locking |

These insights help in tailoring screw gears for specific applications. Moreover, UGNX’s “Manufacturing” module supports CNC programming for producing screw gears. The parametric model directly feeds into toolpath generation, reducing errors in machining. For instance, the helical surfaces of screw gears require precise 5-axis milling, which UGNX can simulate and optimize. By maintaining parametric relationships, any design tweak cascades to the CAM operations, streamlining the entire product development cycle for screw gears.

Mathematical Foundations for Screw Gears Design

The design of screw gears relies heavily on mathematical formulas to define geometry and kinematics. In addition to the involute equations, other key formulas include those for spiral dimensions and contact ratios. For the worm helix, the parametric equations in Cartesian coordinates are: $$x = r \cos(\theta)$$ $$y = r \sin(\theta)$$ $$z = \frac{L \theta}{2\pi}$$ where $r$ is the pitch radius, $\theta$ is the rotation angle in radians, and $L$ is the lead. This spiral representation is used in UGNX’s helix tool. For the worm gear, the tooth thickness at the pitch circle is given by $s = \frac{\pi m_n}{2}$, ensuring proper meshing with the worm. The contact ratio $m_c$ for screw gears, which indicates the average number of teeth in contact, can be estimated as: $$m_c = \frac{\sqrt{r_{a1}^2 – r_{b1}^2} + \sqrt{r_{a2}^2 – r_{b2}^2} – a \sin \alpha}{\pi m_n \cos \alpha}$$ where $r_{a1}$ and $r_{a2}$ are tip radii, $r_{b1}$ and $r_{b2}$ are base radii, and $a$ is the center distance. A higher contact ratio improves the smoothness of screw gears operation.

I often embed these formulas in UGNX expressions to drive dimensions. For example, to calculate the worm length based on the number of threads, I use $l = (n + 2) m_a$, where $n$ is the number of engaged threads. This ensures sufficient contact area in screw gears. Additionally, the self-locking condition for screw gears is checked using the friction angle $\phi$: if $\gamma < \phi$, the screw gears are self-locking, preventing back-driving. In UGNX, I can create a rule-based check that warns the designer if parameters violate this condition. Such mathematical rigor is essential for reliable screw gears design, especially in safety-critical applications like elevators or heavy machinery.

Practical Applications and Benefits of Parametric Screw Gears Modeling

The parametric modeling of screw gears in UGNX has far-reaching applications across industries. In automotive systems, screw gears are used in steering mechanisms for their compactness and precise motion control. By creating parametric models, manufacturers can easily adapt designs for different vehicle models, reducing development time. In industrial machinery, such as conveyor systems, screw gears provide high torque transmission in tight spaces. The parametric approach allows for customization based on load requirements, with quick updates to dimensions like module or pressure angle. I’ve leveraged this in projects where screw gears needed to be scaled for varying speeds, using UGNX to regenerate models in minutes rather than hours.

Another benefit is the facilitation of digital prototyping and testing. With parametric screw gears models, I can perform virtual assembly and interference checks to identify issues early. For instance, in a recent project on packaging equipment, I modeled screw gears with different lead angles and simulated their engagement using UGNX Motion. This revealed vibration patterns that guided design adjustments before physical prototyping. Moreover, the integration with PLM systems ensures that all design variations of screw gears are documented and reusable, supporting standardization efforts. Tables comparing different screw gears configurations can aid in selection, such as:

| Application | Recommended Module | Lead Angle | Reason |

|---|---|---|---|

| Precision Instruments | 1 mm | 3° | Fine control and low backlash |

| Heavy-Duty Lifts | 4 mm | 5° | High load capacity and durability |

| High-Speed Drives | 2 mm | 6° | Efficiency and reduced wear |

These insights underscore the versatility of screw gears in diverse scenarios. By mastering parametric modeling in UGNX, engineers can optimize screw gears for performance, cost, and manufacturability, contributing to more efficient mechanical systems.

Conclusion

In summary, parametric modeling of screw gears using UGNX is a powerful methodology that blends geometric analysis, mathematical formulas, and software tools to create accurate and adaptable designs. From initial sketching to advanced simulation, UGNX supports every step with features like expressions, law curves, and Boolean operations. The parametric nature ensures that changes propagate seamlessly, making it ideal for iterative design and customization of screw gears. As screw gears continue to be vital in transmission systems, mastering these techniques in UGNX can enhance design efficiency and product quality. I encourage engineers to explore parametric modeling for other complex components, leveraging UGNX’s capabilities to innovate in mechanical design. The journey from concept to virtual prototype becomes smoother, ultimately leading to better-performing screw gears in real-world applications.