In the pursuit of enhancing vehicle suspension systems, I have dedicated significant effort to designing and testing an innovative actuator for active suspension applications. The core of this work revolves around a rack and pinion gear mechanism, which I believe offers a robust and efficient solution for converting rotary motion into linear force. Active suspensions, unlike their passive counterparts, promise superior vibration isolation and ride comfort by dynamically controlling the forces between the chassis and wheels. My focus has been on developing a reliable electromagnetic actuator based on the rack and pinion gear principle, analyzing its theoretical performance, and validating it through rigorous bench testing. This document presents a comprehensive account of my journey, from conceptual design to experimental verification, all narrated from my first-person perspective as the principal investigator.

The motivation for this work stems from the limitations observed in other actuator types, such as linear motors and ball screw mechanisms. While linear motors offer simplicity, they often suffer from limited force output and reliability concerns. Ball screw actuators, on the other hand, can struggle with impact resistance and high-frequency control. The rack and pinion gear configuration, however, has shown promising results in prior studies, such as those on energy-regenerative shock absorbers. I was particularly inspired by these applications and sought to design a rack and pinion gear actuator tailored for vehicle active suspensions, optimizing it for both performance and durability.

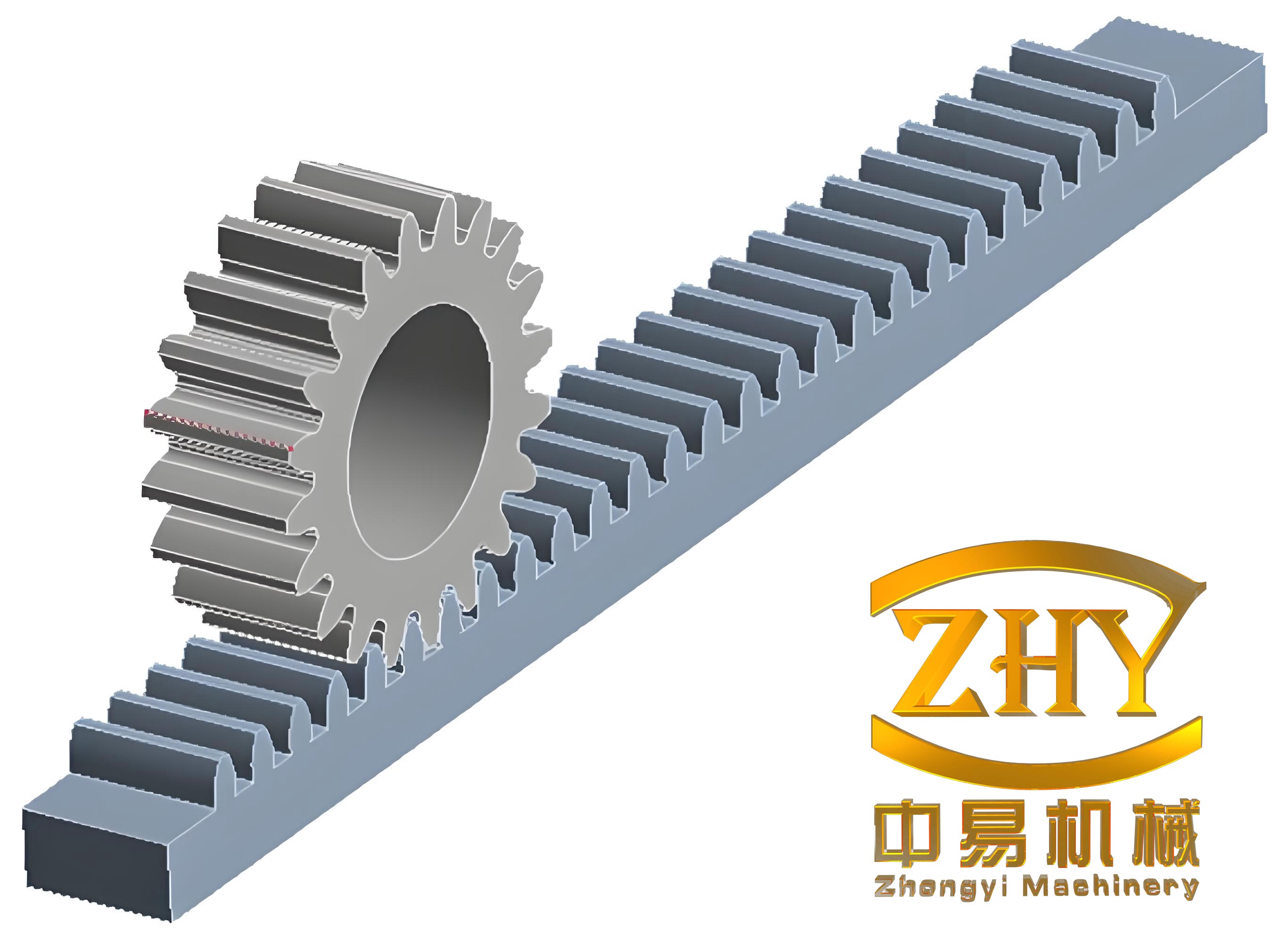

My design process began with a meticulous selection of components to ensure the rack and pinion gear actuator would meet the demanding requirements of automotive environments. The actuator’s structure is fundamentally built around the rack and pinion gear set, which serves as the motion conversion core. I integrated a high-performance AC servo motor as the prime mover, coupled with a planetary gear reducer for torque amplification. The rack and pinion gear assembly consists of a cylindrical rack that engages with a precision gear, all housed within a fixed mounting bracket. To minimize friction and provide guidance, I incorporated a bronze bushing within the housing, eliminating the need for additional linear guides often required with square racks. This design choice streamlined the assembly and reduced potential points of failure.

The selection of the motor and reducer was critical. I followed power-matching and speed-matching methodologies to ensure compatibility. The servo motor I chose has a rated output power of 1000 W, a rated torque of 3.18 N·m, and a rated speed of 3000 rpm. Its torque constant is 0.454 N·m/A, and the rotor inertia is 1.36 kg·cm². For the planetary reducer, I selected a model with a 16:1 reduction ratio, capable of handling an input speed of 3000 rpm and providing an output torque of 130 N·m. The gear in the rack and pinion gear set has a module of 3 and 19 teeth, resulting in a pitch circle radius of 0.0285 m. These parameters form the foundation for the theoretical analysis that follows.

To understand the dynamic behavior of my rack and pinion gear actuator, I delved into a detailed theoretical analysis of two key aspects: response time and active control force. The response time is crucial for real-time suspension control, as it determines how quickly the actuator can react to road disturbances. In an ideal scenario, with a perfectly tuned current controller for the permanent magnet synchronous motor (PMSM), the response time is governed by the current loop’s proportional gain and integral time constants. The control architecture employs vector control with a focus on the q-axis current, as I adopted the i_d = 0 control strategy for its efficiency and simplicity. This strategy ensures all stator current contributes to torque production, minimizing losses and avoiding demagnetization risks.

The mathematical model of the PMSM with current controllers can be represented in a decoupled control block diagram. For the q-axis current control, using a PI controller, the relationship between the commanded current i_q^* and the actual current i_q is given by the closed-loop transfer function:

$$G_{C_{iq}}(s) = \frac{K_{iq} T_{iq} s + K_{iq}}{T_{iq} L_a s^2 + T_{iq}(R_a + K_{iq})s + K_{iq}}$$

Here, \(K_{iq}\) is the proportional gain, \(T_{iq}\) is the integral time constant, \(L_a\) is the stator inductance, and \(R_a\) is the stator resistance. The theoretical step response time, often characterized by rise time, depends directly on these controller parameters. In practice, I tuned these parameters to achieve a fast yet stable response. However, the actual response of the rack and pinion gear actuator is also influenced by mechanical factors, such as inertia and backlash, which I will address later.

The active control force generated by the rack and pinion gear actuator is derived from the electromagnetic torque of the motor. With i_d = 0, the electromagnetic torque \(T_e\) is proportional to the q-axis current:

$$T_e = p_n \psi_f i_q = K_t i_q$$

where \(p_n\) is the number of pole pairs, \(\psi_f\) is the rotor flux linkage, and \(K_t\) is the torque constant. This torque is amplified by the planetary reducer with gear ratio \(i\) and then converted to linear force via the rack and pinion gear. The pitch circle radius of the gear, denoted \(R_g\), is the lever arm for this conversion. Thus, the active control force \(F_a\) exerted by the actuator along the rack’s axis is:

$$F_a = \frac{T_m i}{R_g} = \frac{K_t i_q i}{R_g}$$

This equation reveals a linear relationship between the force and the q-axis current, assuming ideal conditions. For my specific design, with \(K_t = 0.454\) N·m/A, \(i = 16\), and \(R_g = 0.0285\) m, the theoretical force constant is approximately 255 N/A. This linearity is advantageous for control implementation, as it allows for straightforward mapping from desired force to current command.

To validate these theoretical models, I constructed a bench test system. The rack and pinion gear actuator was mounted in a fixed configuration, with its output rod connected in series to a high-precision force sensor. The actuator’s ends were secured to a rigid frame to simulate a constrained condition. I used a dedicated motor tuning software to generate current commands and recorded both the current signals (via the software’s oscilloscope function) and the force output (via a data acquisition system) at a sampling frequency of 1 kHz. This ensured sufficient temporal resolution to capture transient responses. Given safety concerns about motor stall conditions, I limited the current testing range to ±5 A, which is within the motor’s operational limits but below its rated maximum to prevent overheating.

The test procedure involved applying step changes in the q-axis current command from 0 to various setpoints, both positive and negative, to evaluate the actuator’s response in both extension and retraction directions. I measured the rise time for both the current and the force response. The rise time is defined as the time taken for the signal to first reach its steady-state value after a step input. Below is a table summarizing the key parameters of the motor and reducer used in my rack and pinion gear actuator, which are essential for the theoretical calculations.

| Component | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Servo Motor | Rated Power | 1000 W |

| Rated Torque | 3.18 N·m | |

| Rated Speed | 3000 rpm | |

| Torque Constant, \(K_t\) | 0.454 N·m/A | |

| Rotor Inertia | 1.36 kg·cm² | |

| Planetary Reducer | Reduction Ratio, \(i\) | 16 |

| Rated Input Speed | 3000 rpm | |

| Rated Output Torque | 130 N·m | |

| Inertia | 0.5 kg·cm² | |

| Rack and Pinion Gear | Gear Module | 3 |

| Pitch Radius, \(R_g\) | 0.0285 m |

The experimental results provided insightful data. The steady-state active control force exhibited a strong linear relationship with the commanded current, as predicted. I performed a linear regression on the measured force values versus current, yielding the equation:

$$F_a = -259.68 I$$

where \(I\) is the q-axis current in amperes, and the negative sign indicates direction (e.g., negative for contraction). The theoretical force based on the design parameters is \(F_a = \frac{K_t i}{R_g} I = \frac{0.454 \times 16}{0.0285} I \approx 255.02 I\). The slight discrepancy between the experimental coefficient (-259.68) and the theoretical one (255.02) can be attributed to factors like mechanical efficiency, friction losses in the rack and pinion gear, and measurement tolerances. Nonetheless, the linear correlation coefficient was very high, confirming the controllability of the rack and pinion gear actuator.

Regarding response times, the current loop itself demonstrated fast dynamics. The rise times for current step changes were consistently around 10 milliseconds, as shown in the table below. This aligns with the theoretical expectation that the current response is primarily governed by the PI controller tuning. However, the force output rise time was longer and varied with the current magnitude. For smaller current steps (e.g., ±1 A), the force rise time was approximately 25 ms, while for larger steps (e.g., ±5 A), it decreased to about 10 ms. This dependency indicates that mechanical factors play a significant role in the overall response of the rack and pinion gear actuator.

| Current Step (A) | Current Rise Time (ms) | Force Rise Time (ms) | Steady-State Force (N) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 14 | 27 | -209.0 |

| 2 | 11 | 19 | -443.6 |

| 3 | 10 | 16 | -733.8 |

| 4 | 10 | 14 | -960.7 |

| 5 | 9 | 11 | -1352.0 |

| -1 | 12 | 24 | 246.8 |

| -2 | 10 | 20 | 506.5 |

| -3 | 10 | 17 | 762.0 |

| -4 | 11 | 12 | 1063.3 |

| -5 | 10 | 10 | 1373.1 |

I attribute the increased force response time at lower currents to the presence of backlash, or “air gap,” within the rack and pinion gear assembly and mounting interfaces. Backlash refers to the slight clearance between mating gear teeth, which must be taken up before force transmission begins. When the current command is small, the motor torque is low, and it takes longer to overcome static friction and take up the backlash, resulting in a delayed force response. For larger currents, the higher torque accelerates this process, reducing the effective delay. This phenomenon is particularly relevant during direction reversals in active suspension control, where the rack and pinion gear actuator must frequently switch between extension and retraction. Therefore, minimizing backlash is paramount in the design of a high-performance rack and pinion gear actuator.

To further analyze the system dynamics, I considered the equation of motion for the actuator’s mechanical part. The total inertia reflected to the motor shaft includes the motor rotor inertia \(J_m\), the reducer inertia \(J_r\), and the load inertia from the rack and pinion gear and the vehicle suspension components. The equation can be expressed as:

$$J_{total} \frac{d\omega_{rm}}{dt} = T_e – T_{load}$$

where \(J_{total} = J_m + J_r + J_{load}/i^2\), \(\omega_{rm}\) is the mechanical angular velocity of the motor, \(T_e\) is the electromagnetic torque, and \(T_{load}\) includes friction and external forces. The load inertia \(J_{load}\) for a rack and pinion gear system can be approximated by considering the mass of the rack and any attached components. If the rack mass is \(m_r\), then \(J_{load} \approx m_r R_g^2\). This inertia affects the acceleration capability and thus the response time. For my design, with a rack mass of approximately 0.5 kg, \(J_{load} \approx 0.5 \times (0.0285)^2 = 0.000406 \text{ kg·m}^2 = 4.06 \text{ kg·cm}^2\). Reflected through the 16:1 reducer, this adds about \(4.06 / 16^2 = 0.0159 \text{ kg·cm}^2\) to the motor shaft, which is small compared to the motor’s 1.36 kg·cm². Hence, the dominant inertial effects come from the motor and reducer themselves.

The friction in the system, particularly in the rack and pinion gear interface and the bronze bushing, also influences performance. I modeled the friction as a combination of Coulomb friction and viscous damping. The force balance on the rack can be written as:

$$F_a = m_r a + F_{friction} + F_{external}$$

where \(a\) is the rack acceleration, \(F_{friction} = F_c \operatorname{sgn}(v) + c v\) (with \(F_c\) as Coulomb friction, \(v\) as velocity, and \(c\) as viscous damping coefficient), and \(F_{external}\) is any external suspension force. During my bench tests, with the actuator fixed, \(F_{external}\) is zero, and the acceleration is negligible in steady state, so \(F_a \approx F_{friction}\). The linear force-current relationship suggests that the friction characteristics are relatively consistent across the tested range.

Another important aspect is the thermal behavior of the rack and pinion gear actuator. Continuous operation, especially under stall conditions during testing, generates heat in the motor windings. The power loss in the motor is primarily resistive, given by \(P_{loss} = 3 I^2 R\) (for a three-phase motor), where \(R\) is the phase resistance. This heating can affect the torque constant and resistance over time. In my tests, I kept the duty cycle low to avoid thermal runaway, but for real vehicle applications, a thermal management strategy would be necessary. The rack and pinion gear itself, being a mechanical component, is less susceptible to thermal issues but must be lubricated to maintain efficiency.

The control strategy for the rack and pinion gear actuator in an active suspension system would involve a higher-level controller that computes the desired force based on vehicle dynamics (e.g., skyhook or groundhook algorithms). This force command is then translated into a q-axis current command using the inverse of the force-current relationship. The current loop, as implemented in the motor drive, ensures fast tracking. However, the backlash-induced delay must be compensated. One approach is to use a feedforward term that applies a brief current surge during direction changes to quickly take up the slack in the rack and pinion gear. Alternatively, advanced control techniques like adaptive control or observer-based backlash compensation could be employed.

To quantify the impact of backlash, I estimated the angular backlash \(\theta_b\) in the gear mesh. For a gear with module \(m\) and number of teeth \(z\), the backlash in linear terms at the pitch circle is typically a few micrometers to tens of micrometers. Assuming a linear backlash of \(b = 0.05 \text{ mm}\), the equivalent angular backlash at the gear is \(\theta_b = b / R_g = 0.00005 / 0.0285 \approx 0.00175 \text{ rad}\). Reflected to the motor shaft through the reducer, this becomes \(\theta_{b,motor} = \theta_b / i = 0.00175 / 16 \approx 1.094 \times 10^{-4} \text{ rad}\). To move through this angle, the motor must generate sufficient torque to overcome friction. The time required can be approximated from the motor’s torque-acceleration relationship: \(\Delta t \approx \sqrt{2 \theta_{b,motor} J_{total} / T_{available}}\). For a small available torque \(T_{available} = K_t \cdot 1 \text{ A} = 0.454 \text{ N·m}\), and \(J_{total} \approx 1.36 + 0.5 + 0.0159 \approx 1.876 \text{ kg·cm}^2 = 1.876 \times 10^{-4} \text{ kg·m}^2\), we get \(\Delta t \approx \sqrt{2 \times 1.094 \times 10^{-4} \times 1.876 \times 10^{-4} / 0.454} \approx \sqrt{9.06 \times 10^{-8}} \approx 0.0003 \text{ s}\), which is negligible. However, this calculation ignores static friction, which is often the dominant factor. Static friction torque \(T_{sf}\) can be much higher, and the time delay becomes \(\Delta t \approx \theta_{b,motor} J_{total} / (T_{available} – T_{sf})\) if \(T_{available} > T_{sf}\). If \(T_{available}\) is close to \(T_{sf}\), the delay increases significantly, explaining the observed trend.

In terms of energy efficiency, the rack and pinion gear actuator has potential for regeneration. During suspension jounce and rebound, the actuator could act as a generator, converting mechanical energy into electrical energy. This would require a bidirectional power electronic converter and control logic to switch between motoring and generating modes. The rack and pinion gear mechanism is inherently reversible, making it suitable for such energy-regenerative applications. The efficiency of this conversion depends on the losses in the motor, reducer, and gear mesh. The overall efficiency \(\eta\) can be expressed as:

$$\eta = \eta_{motor} \cdot \eta_{reducer} \cdot \eta_{rack and pinion gear}$$

where each \(\eta\) is the respective efficiency (typically 0.9 for the motor, 0.95 for the reducer, and 0.98 for the rack and pinion gear, yielding a total around 0.84). This is an area for future work on my rack and pinion gear actuator design.

The bench test system also allowed me to evaluate the actuator’s frequency response. By applying sinusoidal current commands at various frequencies and measuring the force output, I could construct a Bode plot. However, due to time constraints, I focused on step responses. Nevertheless, the fast current response suggests that the rack and pinion gear actuator could handle frequencies up to at least 50 Hz, which is sufficient for most suspension applications, as road inputs are typically below 20 Hz. The mechanical resonance of the system, determined by the mass of the rack and the stiffness of the suspension attachment, should be kept well above the operating frequency range to avoid oscillations.

In summary, my design and testing of the rack and pinion gear actuator have yielded promising results. The linear relationship between force and current simplifies control integration, and the response times are generally adequate for active suspension duties. The key challenge identified is the backlash in the rack and pinion gear assembly, which degrades response during direction changes, especially at low force commands. To mitigate this, future iterations of the rack and pinion gear actuator should employ anti-backlash gears or preload mechanisms. Additionally, using higher precision components and tighter tolerances in the rack and pinion gear mesh would reduce the air gap. From a control perspective, implementing backlash compensation algorithms will be essential.

Looking ahead, the integration of this rack and pinion gear actuator into a full vehicle active suspension system presents exciting opportunities. The actuator would be installed at each wheel, replacing traditional dampers and springs. A central controller would process sensor data from accelerometers and position sensors to compute optimal forces in real time. The rack and pinion gear actuator’s ability to generate both positive and negative forces allows for complete control over the wheel’s motion relative to the chassis. This can significantly improve ride comfort, handling, and safety. Moreover, the potential for energy regeneration could make the system more sustainable, aligning with trends in vehicle electrification.

In conclusion, my thorough investigation into the rack and pinion gear actuator has reinforced its viability for advanced suspension systems. The theoretical models developed provide a solid foundation for understanding its dynamics, and the experimental data validate these models with reasonable accuracy. The rack and pinion gear mechanism proves to be a robust and efficient choice for motion conversion in this context. By addressing the backlash issue through design improvements and advanced control, the performance of the rack and pinion gear actuator can be further enhanced, paving the way for its adoption in next-generation vehicles. I am confident that continued research and development on rack and pinion gear based actuators will contribute significantly to the evolution of automotive suspension technology.