As a researcher deeply involved in the field of precision mechanical transmissions, I have witnessed a significant surge in interest towards the planetary roller screw assembly over recent years. This mechanical device, capable of converting rotary motion into linear motion and vice versa, presents a compelling alternative to traditional ball screws and hydraulic systems in demanding applications. The drive towards all-electric aircraft and weapon systems, coupled with industrial needs in petroleum, chemical processing, and machine tools for high-thrust, high-precision, high-frequency response, and long-life linear actuation, has positioned the planetary roller screw assembly at the forefront of actuation technology. In this comprehensive article, I will delve into the fundamental principles, structural variations, current research landscape, and the critical technological challenges surrounding the planetary roller screw assembly. My aim is to synthesize existing knowledge and present a detailed, first-person perspective on its development, employing numerous formulas and tables to encapsulate the core concepts and data.

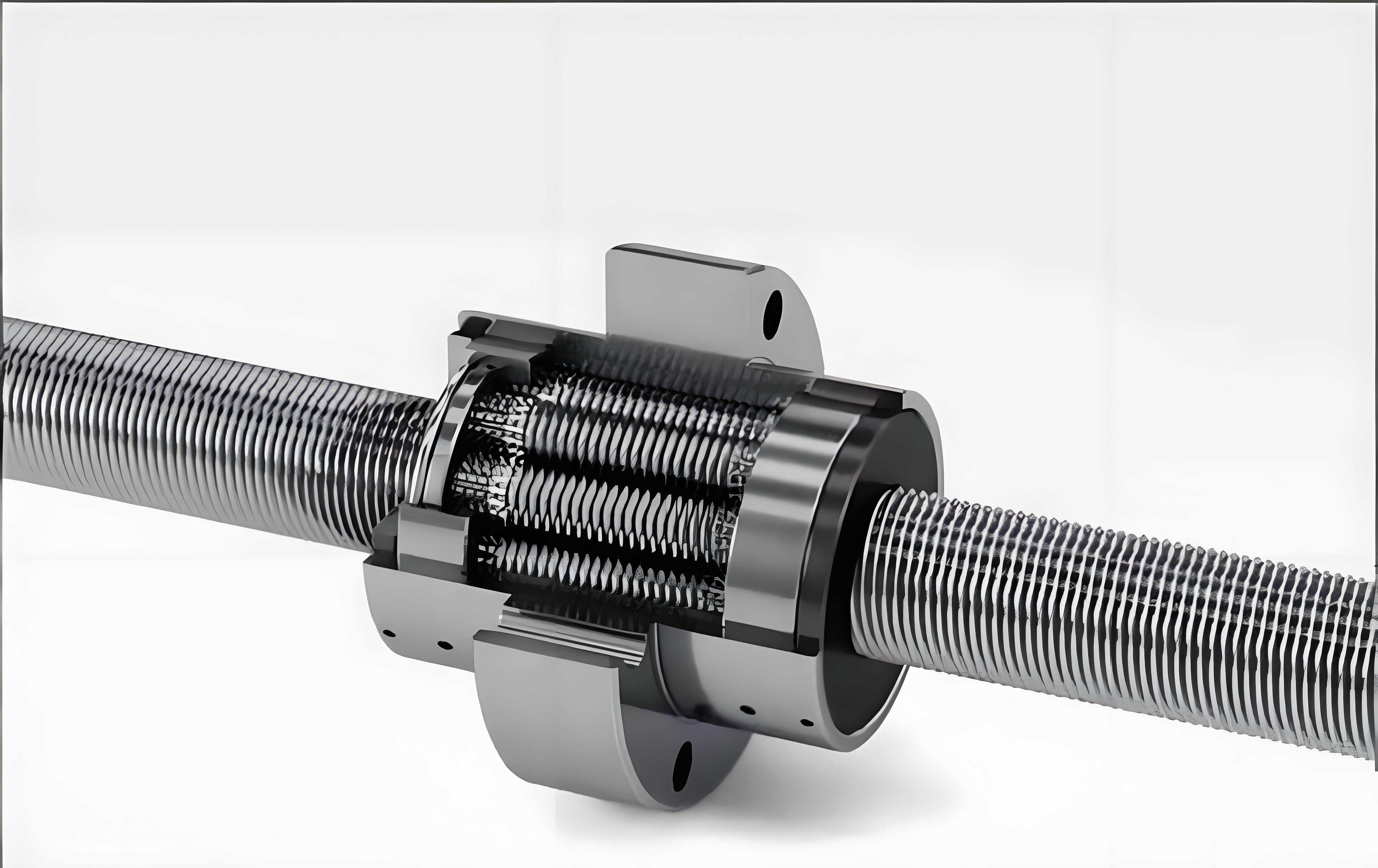

The fundamental operation of a standard planetary roller screw assembly is elegant in its simplicity and efficiency. The core components are the screw, the planetary rollers, and the nut. The screw typically features a multi-start thread with a 90-degree thread angle. The rollers, which are distributed around the screw, have a single-start thread with a spherical profile, and the nut possesses an internal thread matching the screw’s lead and thread angle. When the screw rotates, the rollers engage with both the screw and the nut. Due to the kinematic constraints—often enforced by spur gears on the roller ends meshing with an internal ring gear in the nut—the rollers undergo both planetary revolution around the screw axis and rotation about their own axes, all while maintaining pure rolling contact without relative axial slip. This multi-point contact mechanism is the source of the superior load capacity and durability of the planetary roller screw assembly. The basic kinematic relationship governing the linear displacement per screw revolution, or the lead (L), is directly tied to the screw’s lead (L_s) and the ratio of the screw’s pitch diameter to the roller’s pitch diameter. A simplified expression for a standard configuration is given by:

$$ L = L_s \cdot \left(1 + \frac{D_s}{D_r}\right) $$

where \( D_s \) is the screw’s effective contact diameter and \( D_r \) is the roller’s effective contact diameter. This formula highlights how the design parameters intrinsically link rotational input to linear output. The performance advantages of the planetary roller screw assembly over ball screws are substantial, including a higher load capacity per unit size, better suitability for high-speed and high-acceleration environments, reduced noise and vibration, and enhanced reliability in harsh conditions. These attributes make the planetary roller screw assembly a cornerstone for next-generation electromechanical actuators (EMAs).

Through my analysis and review of existing designs, I have categorized the primary structural configurations of the planetary roller screw assembly into five distinct types, each tailored for specific operational requirements. The table below provides a comparative summary of these configurations, their operational principles, and typical application domains.

| Configuration Type | Key Operational Feature | Primary Advantages | Common Applications & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard PRS | Screw is driver; rollers have spur gears meshing with internal nut ring gear. | Robust, suitable for harsh environments, high load capacity, long stroke. | Heavy machinery, machine tools, aerospace primary actuation. Failure modes: material fatigue, thread wear. |

| Reverse PRS (Inverted) | Nut is driver (often as motor rotor); screw provides linear output. Roller gears mesh with screw-end gears. | Enables compact EMA design, high integration, good for high-speed operation. | Integrated electromechanical actuators (EMAs) for aerospace. Requires long, precise nut threads. |

| Recirculating PRS | Rollers have axial “grooves” instead of threads; a cam ring resets roller position periodically. | Allows for very fine leads, high positional accuracy, increased number of contact points. | Precision medical devices, printing equipment. Potential for vibration/noise at high speed due to recirculation impact. |

| Bearing Ring PRS | Nut assembly includes a rotating bearing ring; thrust load is transferred via roller bearings. | Minimizes friction, maximizes transmission efficiency by distributing load circumferentially. | Applications requiring ultra-high efficiency and smooth motion. Complexity in assembly. |

| Differential PRS | Screw, rollers, and nut have different thread angles (β > α > γ), altering contact points and lead. | Provides a high gear reduction ratio (motion transformation) in a compact space. | Applications needing high reduction ratios at medium speeds. Lower load capacity due to edge-contact stresses. |

The selection of a specific planetary roller screw assembly configuration depends heavily on the application’s priority: whether it is maximum thrust, precision, speed, efficiency, or integration capability. My own design experiments often begin with the standard or reverse configurations for general high-performance EMA prototyping.

The mechanical design and parameter matching for a planetary roller screw assembly are foundational. Based on established geometric relations, I consistently use the following set of formulas to ensure proper kinematic function and load distribution in a standard planetary roller screw assembly. These relationships are critical for avoiding binding and ensuring smooth operation.

1. Thread Start Relationship: For proper meshing, the number of starts on the screw (\(n_s\)) and nut (\(n_n\)) must satisfy:

$$ n_n = n_s = k + 2 = \frac{D_n}{D_r} $$

where \( k = \frac{D_s}{D_r} \), and \(D_n\) is the nut’s effective contact diameter.

2. Roller Profile Radius: To maintain a 45° contact angle with 90° thread flanks on the screw and nut, the spherical radius (R) of the roller thread profile is:

$$ R = \frac{D_r}{2 \sin 45^\circ} = \frac{D_r}{\sqrt{2}} $$

3. Maximum Number of Rollers: The theoretical maximum number of rollers (\(n_{max}\)) is limited by the circumferential space:

$$ n_{max} \approx \frac{\pi D_m}{D_r} $$

where \( D_m = (k + 1)D_r \) is the planetary pitch diameter.

4. Gear Teeth Relationship: For the synchronization gears on the roller ends and the internal ring gear, the number of teeth must satisfy:

$$ z_n = (k + 2) z_r $$

where \(z_n\) and \(z_r\) are the number of teeth on the internal ring gear and each roller gear, respectively.

5. Phase Matching During Assembly: To avoid conflict between thread meshing and gear meshing, if all roller threads are cut starting at the same phase, each successive roller must be rotated about its axis by an angle \(\theta\) during assembly:

$$ \theta = \frac{n_s}{n} \times 2\pi $$

where \(n\) is the actual number of rollers installed.

Adhering to these formulas is essential, but I have found that the practical challenge lies in manufacturing tolerances and the phase matching between the threaded section and the geared ends of the rollers. Even minor deviations can lead to increased backlash, uneven load sharing, and premature wear in the planetary roller screw assembly.

The mechanical analysis of a planetary roller screw assembly extends far beyond kinematics into the realms of statics, dynamics, contact mechanics, and life prediction. Drawing from classical bearing theory and my own computational studies, several key performance metrics can be modeled. The load capacity, for instance, is a direct function of the number of contact points and the material properties. A generalized formula for the basic dynamic load rating (\(C_a\)) of a planetary roller screw assembly, analogous to rolling bearing calculations, is often expressed as:

$$ C_a = f_c \cdot (\cos\alpha)^{0.86} \cdot z^{2/3} \cdot D_w^{1.8} \cdot \tan\alpha \cdot (\cos\lambda)^{1/3} $$

Here, \(f_c\) is a geometry and material factor, \(\alpha\) is the contact angle (typically 45°), \(z\) is the total number of active contact points, \(D_w\) is the effective diameter of the roller at the contact (often approximated as \(D_w = 2.5 \cdot p \cdot D_r / \sqrt{2}\), where \(p\) is the pitch), and \(\lambda\) is the lead angle. The efficiency (\(\eta\)) of a well-lubricated planetary roller screw assembly is primarily governed by the friction in the rolling contacts and can be estimated by:

$$ \eta = \frac{\tan\lambda}{\tan(\lambda + \phi)} $$

where \(\phi = \arctan(\mu)\), and \(\mu\) is the effective coefficient of rolling friction. For a typical lead angle \(\lambda\) of a few degrees and a low \(\mu\), efficiencies above 90% are achievable, which I have corroborated in bench-top tests. The fatigue life calculation, following the ISO standard approach for rolling contacts, models the L10 life (the life at which 90% of a population survives) as:

$$ L_{10} = \left( \frac{C}{f_m \cdot P} \right)^3 \times 10^6 \text{ revolutions} $$

where \(C\) is the dynamic load rating, \(P\) is the equivalent dynamic load, and \(f_m\) is a correction factor (e.g., 0.75 for single nut, 1.5 for preloaded double nut designs). A more comprehensive life model accounting for a reliability factor S (survival probability) is:

$$ L_F = L_{10} \cdot \left[ \frac{L_0}{L_{10}} + \left(1 – \frac{L_0}{L_{10}}\right) \left( \frac{\log S}{\log 0.9} \right)^{9/10} \right] $$

where \(L_0\) is a minimum guaranteed life, often taken as 0.05\(L_{10}\).

However, these analytical models often rely on equivalency methods, treating the roller contacts as analogous to ball bearings. My finite element analysis (FEA) and multi-body dynamics simulations reveal more nuanced behaviors. For example, the load distribution across the multiple engaged threads of a planetary roller screw assembly is not uniform. The following table summarizes key findings from my simulation studies on load sharing and stress states under different operating conditions for a standard configuration.

| Operating Condition | Load Distribution Characteristic | Maximum Contact Stress Trend | Implication for Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| Static, Pure Axial Load | Highly non-uniform; end threads near load application carry highest share. | Peak stress occurs at the first few engaged threads on the screw and nut. | Underscores need for precise lead accuracy and potential for localized wear initiation. |

| Dynamic, Moderate Speed | Distribution becomes more even compared to static case due to elastic averaging. | Stress amplitude fluctuates cyclically; value depends on instantaneous roller position. | High-cycle fatigue is a critical failure mode; material surface finish is crucial. |

| High Acceleration/Deceleration | Significant dynamic load spikes; inertia of rollers and nut affects sharing. | Transient stress peaks can exceed static values, especially during direction reversal. | Prevents use of simple static models for high-performance servo applications. |

| With Manufacturing Errors (e.g., lead error) | Extreme non-uniformity; a single thread pair may carry most of the load. | Localized stress concentration increases dramatically, severely reducing life. | Highlights paramount importance of manufacturing precision in screw, roller, and nut threads. |

My dynamic simulations further illustrate that sliding tendencies, albeit small, exist at the contact ellipses, especially under combined loads or misalignment. This micro-slip contributes to friction losses and heat generation, factors that are often oversimplified in basic efficiency formulas. The thermal management of a planetary roller screw assembly, particularly in high-duty-cycle applications, thus becomes a coupled mechanical-thermal problem. The heat generation rate (\( \dot{Q} \)) can be approximated from power loss:

$$ \dot{Q} = T_{in} \cdot \omega \cdot (1 – \eta) $$

where \(T_{in}\) is the input torque and \(\omega\) is the angular velocity. This heat must be dissipated to prevent thermal expansion from degrading preload, accuracy, and lubricant performance.

The global research and production landscape for the planetary roller screw assembly shows a distinct asymmetry. Internationally, companies like Rollvis (Switzerland), SKF (Sweden), Moog, and Exlar (USA) have mature product lines spanning diameters from 1 mm to 150 mm, with leads down to 0.1 mm and linear speeds up to 2 m/s. Their products are integral to aerospace EMAs, precision machine tools, and robotics. In contrast, domestic capability, while present, often lags in consistency, precision, and performance under extreme conditions. The gap stems not from a lack of design understanding but from challenges in manufacturing, material science, and comprehensive testing. My engagement with industry suggests that the production of a high-quality planetary roller screw assembly hinges on several intertwined key technologies, which I perceive as the primary frontiers for advancement.

1. Integrated Design for Manufacturability: The design formulas mandate integer ratios between diameters and tooth counts. This necessitates a co-design approach where thread grinding and gear cutting processes are planned simultaneously. For small-diameter planetary roller screw assemblies, gear hobbling might damage the critical load-bearing threads, making precision shaping or skiving preferable. The sequence of operations—threading first or gearing first—impacts final quality and phase alignment.

2. Phase Synchronization of Threads and Gears: This is arguably the most delicate assembly challenge. The theoretical phase-matching angle \(\theta\) is only valid if every roller’s thread start line is perfectly aligned with its gear tooth datum. Manufacturing variances break this ideal condition. Common workarounds, like increasing thread clearance or axially shifting rollers, compromise load capacity or limit travel. Advanced manufacturing with synchronized multi-axis CNC machining for rollers is likely the ultimate solution, but it increases cost significantly.

3. Development of a Dedicated Mechanical Analysis Framework: Relying on equivalent ball screw or bearing models is insufficient for optimizing a planetary roller screw assembly. We need high-fidelity models that account for the true multi-start thread geometry, the spherical contact profiles, the elastic deformation of all components, and the system’s boundary conditions. My work involves developing such models using explicit dynamics and nonlinear FEA to predict stiffness, natural frequencies, and dynamic response accurately. The axial stiffness (\(K_{ax}\)) of a preloaded planetary roller screw assembly, for instance, depends on the series stiffness of all contacting interfaces and can be modeled as:

$$ \frac{1}{K_{ax}} \approx \frac{1}{N_r \cdot N_t} \sum_{i=1}^{N_r} \sum_{j=1}^{N_t} \left( \frac{1}{K_{s-r}^{ij}} + \frac{1}{K_{r-n}^{ij}} \right) $$

where \(N_r\) is the number of rollers, \(N_t\) is the number of engaged threads per roller, and \(K_{s-r}^{ij}\) and \(K_{r-n}^{ij}\) are the nonlinear contact stiffnesses at the i-th roller and j-th thread interface with the screw and nut, respectively, derived from Hertzian contact theory.

4. Tribology, Lubrication, and Thermal Management: The performance and life of a planetary roller screw assembly are acutely sensitive to lubrication. The choice of grease or oil, its base stock, additives, and viscosity must suit the operating temperature range, speed, and load. In aerospace applications, wide temperature extremes from -55°C to 150°C are common. Lubricant starvation or degradation can shift the failure mode from subsurface fatigue to adhesive wear or abrasive wear. Furthermore, friction-induced heating affects dimensional stability. A coupled thermal-structural analysis is essential for high-speed designs. The flash temperature rise at a contact (\(\Delta T\)) can be estimated using Blok’s formula:

$$ \Delta T \propto \frac{\mu \cdot p \cdot v}{\sqrt{k \cdot \rho \cdot c}} $$

where \(\mu\) is the friction coefficient, \(p\) is the contact pressure, \(v\) is the sliding velocity, and \(k\), \(\rho\), \(c\) are the thermal conductivity, density, and specific heat of the contacting materials.

5. Material Science and Heat Treatment: The threads undergo high cyclic contact stresses. Material selection and hardening are critical. Common choices include case-hardening steels like AISI 8620 or through-hardening steels like AISI 52100 for components. For corrosion resistance or high-temperature use, martensitic stainless steels like AISI 440C or managing steels are employed. The target surface hardness for screw and nut threads is typically HRC 58-62, while rollers may require HRC 62-64 due to their smaller size and higher stress cycles. Heat treatment processes like carburizing, induction hardening, or nitriding must be meticulously controlled to achieve the desired hardened depth without causing excessive distortion or residual stresses that could affect accuracy. The table below summarizes typical material-process combinations and their trade-offs.

| Material Class | Example Grades | Recommended Heat Treatment | Key Properties & Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low-Alloy Case-Hardening Steel | AISI 8620, 9310 | Carburizing and quenching | Excellent core toughness with hard, wear-resistant case. General-purpose high-load planetary roller screw assemblies. |

| Through-Hardening Bearing Steel | AISI 52100, SUJ2 | Through hardening and tempering | High uniform hardness, good wear resistance. Used for rollers and precision screws. Sensitive to size distortions. |

| Corrosion-Resistant Steel | AISI 440C, X30CrMoN15-1 | Hardening and tempering | Good hardness (HRC 58+) and corrosion resistance. For applications in corrosive or clean environments (e.g., food, medical). |

| High-Strength Managing Steel | 18Ni (300), 18Ni (350) | Aging (precipitation hardening) | Ultra-high strength, good dimensional stability during heat treatment. For extreme performance or weight-critical aerospace planetary roller screw assemblies. |

| Nitriding Steel | 41CrAlMo7, Nitralloy 135M | Gas or plasma nitriding | Produces a hard surface layer with minimal distortion. Good for complex-shaped nuts. Case depth is shallower than carburized layers. |

6. System Integration and Validation: A planetary roller screw assembly does not operate in isolation. In an EMA, its performance is coupled with the servo motor, controller, feedback sensors, and structural mounts. Dynamic interactions, such as torsional resonances or axial compliance affecting bandwidth, must be considered during system design. Furthermore, comprehensive validation testing—including life testing under spectrum loads, environmental testing (temperature, humidity, contamination), and performance mapping (efficiency vs. speed/load)—is indispensable but costly. Developing accelerated life test protocols and accurate digital twins for the planetary roller screw assembly would significantly reduce development time and risk.

7. Exploration of Novel Configurations: While the five established forms cover many needs, there is room for innovation. Concepts like tandem or parallel roller arrangements to increase stroke without exceedingly long components, or hybrid designs incorporating magnetic preload or active damping elements, could address niche requirements. My ongoing research includes conceptualizing a “split-path” planetary roller screw assembly where different sets of rollers handle different load components to optimize stiffness and life.

In conclusion, the planetary roller screw assembly represents a sophisticated and highly capable mechanical transmission element whose time has come for widespread adoption in high-performance systems. Its advantages in load density, speed capability, and durability are well-substantiated. However, mastering its design, manufacture, and application requires overcoming significant interdisciplinary challenges. From my perspective, future progress will be driven by advances in multi-physics modeling and simulation, breakthroughs in precision manufacturing and metrology, the development of specialized lubricants and surface engineering techniques, and the creation of robust system integration methodologies. As these key technologies mature, I am confident that the planetary roller screw assembly will transition from a specialized component to a mainstream solution, enabling a new generation of efficient, reliable, and powerful electromechanical motion systems across aerospace, industrial automation, and beyond. The journey involves not just incremental improvements but a holistic system-level approach to unlocking the full potential of this remarkable mechanism.