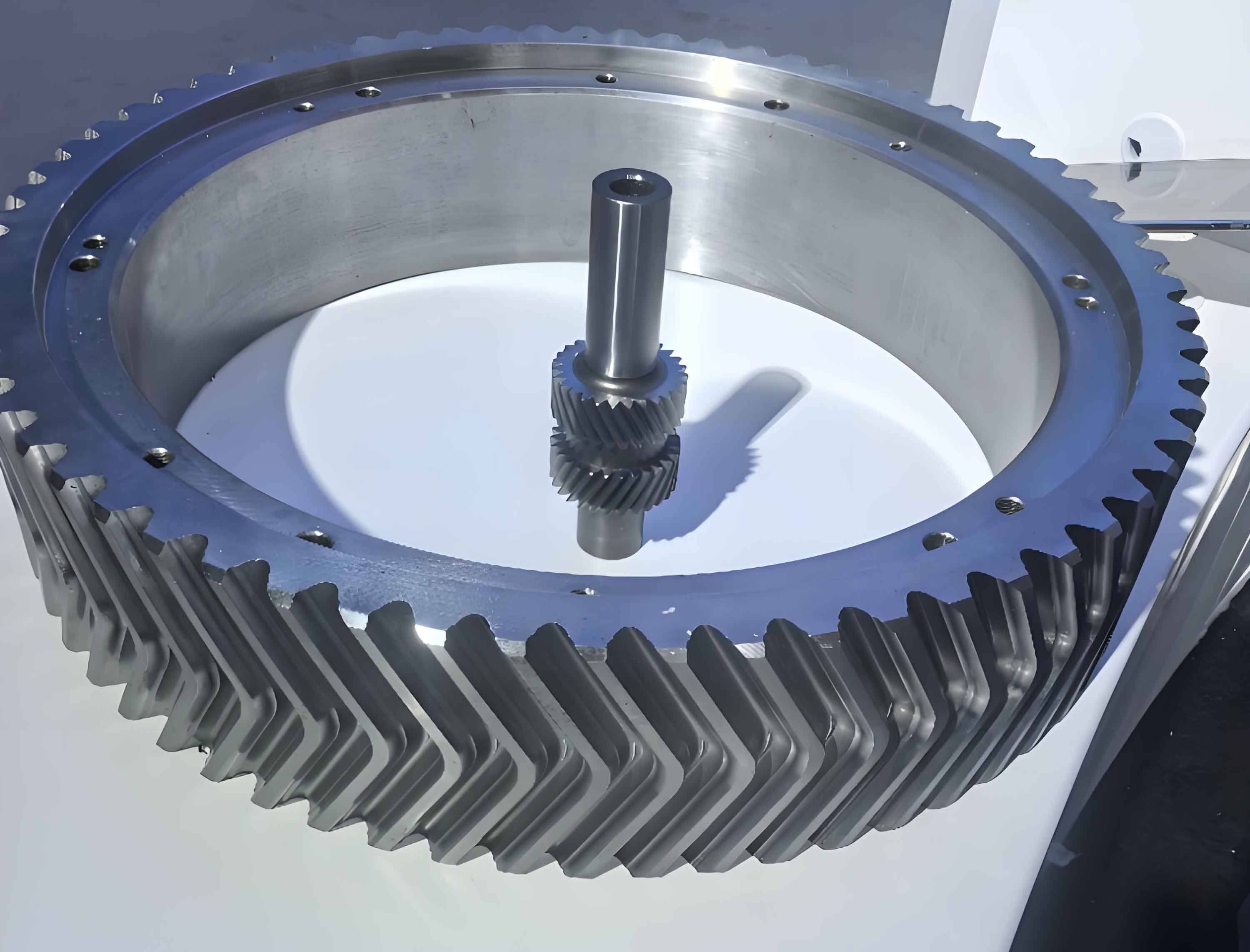

In my extensive experience with gear manufacturing, particularly in the realm of heavy-duty power transmission, the加工 of herringbone gears presents unique challenges and opportunities. Herringbone gears, characterized by their dual helical teeth that form a ‘V’ shape, are critical components in various industrial applications such as marine propulsion, rolling mills, and heavy machinery. Their design inherently balances axial thrust forces, leading to smoother operation and higher load capacity compared to single helical gears. However, achieving precise alignment of the tooth slots on both halves of a herringbone gear during hobbing is paramount to ensuring optimal meshing, minimal noise, and extended service life. This article delves into a refined computational method for adjusting the tooth slot position during the hobbing process, a technique I have developed and applied to enhance the geometric accuracy and production efficiency of these complex components.

The evolution of herringbone gear design has seen a shift from closed-width structures to open-width configurations. In open-width herringbone gears, a central relief groove or空刀槽 is incorporated along the face width. This design allows for more effective hobbing operations, as it provides space for the hob to exit and re-enter during the cutting of the two opposing helices. The primary advantage lies in the significant improvement of geometric precision, particularly in tooth alignment and profile accuracy. The standard manufacturing sequence involves first hobbing one helix (either left-hand or right-hand) to completion. Then, using precise scribing techniques, the positions of the tooth slots and tooth crests are meticulously transferred from the finished side to the uncut side. This scribed reference serves as a guide for machining the second helix, with the ultimate goal of ensuring that the tooth trace extensions from both sides intersect precisely at the centerline of the full face width. While traditional manual adjustment based on visual inspection of tool marks against these scribed lines can achieve errors within a certain tolerance, it is often time-consuming, prone to inaccuracies, and relies heavily on operator skill. The method I advocate replaces this iterative trial-and-error approach with a deterministic, calculation-based adjustment, drastically reducing setup time and improving consistency.

The core challenge in machining open-width herringbone gears is the precise alignment of the tooth slot on the second side relative to the scribed reference from the first side. After roughing or initial trial cuts on the second side, the actual tooth slot position will inevitably deviate from the ideal target position defined by the scribed lines. This deviation, if not corrected before final finishing cuts, leads to misalignment, increased transmission error, and potential premature failure. The traditional adjustment process involves stopping the machine, visually comparing the hob cut (tool mark) with the scribed line, and manually shifting the hob axis vertically—a process repeated multiple times during fine finishing. This is where the calculation-based method proves invaluable. By quantifying the deviation through simple measurement and applying a trigonometric calculation, the required vertical adjustment of the hob head (or workpiece, depending on machine configuration) can be determined accurately in a single step.

The mathematical principle underlying this adjustment is rooted in the geometry of the helical tooth. Consider a herringbone gear where one helix is complete. Points A and B are scribed reference points on the tooth crest line for the target slot position on the second side. After a trial cut, the actual slot is positioned such that its corresponding points are A’ and B’. The critical measured deviation is the horizontal offset between these lines at the reference diameter, typically at the pitch line for simplicity. Let’s define W1 as the measured distance from a fixed datum to the scribed target line and W2 as the distance to the actual cut slot line at the same axial position. The horizontal error ΔW is then:

$$ \Delta W = W_2 – W_1 $$

This ΔW represents how far the slot is shifted laterally from its intended position. To correct this, we adjust the hob vertically. The relationship between the required vertical adjustment Δh and the horizontal error ΔW is governed by the helix angle β (the angle at the reference or pitch diameter). From the geometry of a right triangle formed by the helix lead, the adjustment is:

$$ \Delta h = \frac{\Delta W}{\tan(\beta)} $$

Where:

- Δh is the vertical adjustment amount of the hob head (positive for upward movement, negative for downward).

- ΔW is the horizontal positional error of the tooth slot (W₂ – W₁).

- β is the helix angle of the herringbone gear at the reference diameter (often the pitch diameter).

This formula is elegantly simple yet powerful. It transforms a two-dimensional alignment problem into a one-dimensional vertical adjustment, directly calculated from easily obtainable measurements.

To solidify understanding, let’s explore the derivation and practical considerations in detail. The helix angle β is a fundamental parameter for any helical or herringbone gear. It is related to the gear’s geometry by:

$$ \tan(\beta) = \frac{\pi \cdot m_n \cdot z}{d} = \frac{\pi \cdot d}{P_z} $$

Where m_n is the normal module, z is the number of teeth, d is the reference pitch diameter, and P_z is the lead of the helix. For a standard herringbone gear, the two helices have equal but opposite helix angles. When performing the adjustment for the second helix, we use the absolute value of β. The measurement of W1 and W2 is typically performed using a height gauge or a coordinate measuring machine on the gear blank itself, referencing from a machined datum face or the gear’s bore. Accuracy here is critical; even small measurement errors can be amplified if the helix angle is small (as tan(β) becomes small, Δh becomes large and sensitive). Therefore, I recommend using dial indicators or digital probes with at least 0.01 mm resolution. The following table summarizes the key parameters and their roles in the adjustment process for herringbone gears.

| Symbol | Parameter | Description | Typical Units | Measurement Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | Helix Angle | Angle of tooth spiral at reference diameter. Fundamental for calculating adjustment. | Degrees or Radians | From gear design drawing or calculated from gear data (module, teeth, lead). |

| W₁ | Target Slot Position | Distance from datum to the scribed reference line representing the ideal tooth slot center. | Millimeters (mm) | Precision height gauge or CMM against scribed line on gear blank. |

| W₂ | Actual Slot Position | Distance from same datum to the edge of the trial-cut tooth slot after initial hobbing. | Millimeters (mm) | Same as W₁, measured on the machined trial cut. |

| ΔW | Horizontal Error | Difference between actual and target positions (W₂ – W₁). Positive if slot is shifted to one side. | Millimeters (mm) | Calculated from W₁ and W₂ measurements. |

| Δh | Vertical Adjustment | Required vertical movement of the hob head to correct the horizontal error ΔW. | Millimeters (mm) | Calculated using Δh = ΔW / tan(β). Applied via machine’s vertical slide with dial indicator. |

The implementation of this calculation-based method follows a systematic procedure. First, after completing the hobbing of the first helix of the herringbone gear and performing the precise scribing operation, the gear is set up for machining the second helix. An initial roughing or trial cut is made to a shallow depth, just enough to clearly define the tooth slot profile. The machine is then stopped. Using measurement tools, an operator measures the distances W1 and W2 at a defined reference plane perpendicular to the gear axis. It is often practical to measure at two or three points along the face width to check for consistency and average any minor variations. From these, ΔW is computed. With the known helix angle β, the vertical adjustment Δh is calculated using the formula. The next step is critical: the machine’s feed mechanism is disengaged (often by switching to manual mode), and the hob head is adjusted vertically by the exact amount Δh. This is done using a dial indicator mounted on the machine column to measure the vertical movement accurately. Once adjusted, the feed is re-engaged, and the hobbing process continues, typically proceeding directly to finish cuts. The entire sequence, from measurement to adjustment, can often be completed in a fraction of the time required for multiple visual trial-and-error adjustments.

To illustrate the calculation with concrete numbers, consider a herringbone gear with the following specifications: a normal module of 8 mm, 50 teeth, a reference pitch diameter of 415 mm, and a helix angle β of 25°. After a trial cut on the second helix, measurements show W1 = 150.00 mm and W2 = 150.30 mm. Therefore, ΔW = 0.30 mm. The required vertical adjustment is:

$$ \Delta h = \frac{0.30 \, \text{mm}}{\tan(25^\circ)} \approx \frac{0.30}{0.4663} \approx 0.643 \, \text{mm} $$

This means the hob head needs to be raised by approximately 0.643 mm to shift the tooth slot leftwards (assuming the sign convention aligns with the machine geometry). The sensitivity of the adjustment is evident; a small horizontal error of 0.3 mm translates to a vertical move of over 0.64 mm due to the helix angle. The inverse relationship with tan(β) means that herringbone gears with smaller helix angles require larger vertical adjustments for the same horizontal error, necessitating even more precise measurement.

I have found that organizing common scenarios and correction factors can streamline the process further. The table below provides a quick reference for vertical adjustment Δh based on typical horizontal errors ΔW for a range of helix angles common in herringbone gears.

| ΔW (mm) | β = 15° | β = 20° | β = 25° | β = 30° | β = 35° |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.10 | 0.373 | 0.275 | 0.214 | 0.173 | 0.143 |

| 0.20 | 0.746 | 0.549 | 0.429 | 0.346 | 0.286 |

| 0.30 | 1.119 | 0.824 | 0.643 | 0.520 | 0.429 |

| 0.40 | 1.492 | 1.099 | 0.857 | 0.693 | 0.572 |

| 0.50 | 1.866 | 1.374 | 1.072 | 0.866 | 0.715 |

The advantages of this computational adjustment method for herringbone gears are manifold. Firstly, it significantly enhances precision. By replacing visual estimation with quantitative measurement and calculation, the alignment error can be reduced to a level primarily limited by measurement accuracy and machine backlash, often well below 0.05 mm. Secondly, it drastically improves production efficiency. What used to require several iterative adjustments—each involving machine stoppage, inspection, manual tweaking, and restart—now typically requires just one calculated adjustment after the trial cut. This reduction in non-cutting time is substantial, especially in batch production of herringbone gears. Thirdly, it reduces reliance on operator skill and judgment, making the process more robust and repeatable. A junior operator following the prescribed measurement and calculation steps can achieve results comparable to a seasoned expert using the old method. Fourthly, it minimizes material waste by reducing the number of corrective cuts needed, which is particularly important for large, expensive herringbone gear forgings.

However, successful application requires attention to several practical details. The machine tool must have a reliable and precise vertical adjustment mechanism for the hob head or workpiece. Backlash in the lead screw or gibs must be accounted for; I recommend always approaching the final adjustment position from the same direction to eliminate play. Environmental factors like temperature variation can affect measurement accuracy, so controlling the workshop climate is beneficial. Furthermore, the scribing process itself must be highly accurate, as any error in the reference lines will propagate through the adjustment. For closed-width herringbone gears (without a central groove), the principle still applies, but the hobbing strategy differs, often requiring plunge cutting or specialized hobs. The calculation method can be adapted, but access for measurement might be more challenging.

Beyond the basic formula, we can derive related expressions for different machine configurations or quality control checks. For instance, the angular error in tooth trace alignment Δθ (in radians) over the face width F can be estimated from the horizontal error ΔW as:

$$ \Delta \theta \approx \frac{\Delta W}{F} $$

This is useful for verifying overall gear quality standards. Additionally, for machines where the workpiece is adjusted vertically instead of the hob, the formula remains identical because the relative motion is the same. The calculation also integrates seamlessly with modern CNC gear hobbing machines. While the manual method described is for conventional machines, on CNC machines, the measured ΔW can be input into the control system, which can automatically compute and execute the tool path offset, further automating the process for herringbone gears.

In my practice, I have applied this method to herringbone gears ranging from 500 mm to over 3000 mm in diameter, with helix angles from 15° to 35°. The consistency of results has been remarkable. A case study involved a large herringbone gear for a steel mill drive. Using the traditional method, aligning the second helix took an average of 4.5 hours of adjustment time after roughing. After implementing the calculation-based adjustment, this time was reduced to approximately 45 minutes—a time saving of over 85%. Moreover, the final tooth alignment quality, measured via coordinate measuring machine, showed a standard deviation improvement of nearly 60%, confirming the superior precision. This translates directly into smoother operation, higher load-sharing among teeth, and reduced maintenance downtime for the machinery employing these herringbone gears.

To further optimize the process for herringbone gears, I recommend establishing a standardized work instruction sheet that includes the following steps: 1) Verify gear blank and scribing data. 2) Perform trial cut on second helix to a defined depth. 3) Measure W1 and W2 at prescribed locations (record in a log table). 4) Calculate ΔW and Δh. 5) Perform vertical adjustment using a dial indicator, documenting the before-and-after readings. 6) Proceed with finish hobbing. This documentation not only ensures consistency but also provides valuable data for statistical process control, helping to identify trends or drifts in machine performance over time.

In conclusion, the precise adjustment of tooth slot position during the hobbing of herringbone gears is a critical factor in achieving their full performance potential. The computational method I have detailed, based on the fundamental trigonometric relationship between horizontal error and vertical adjustment via the helix angle, offers a superior alternative to traditional trial-and-error techniques. By embracing this calculated approach, manufacturers can achieve higher geometric accuracy, significantly reduce auxiliary production time, lower dependency on operator skill, and enhance overall process robustness. As the demand for high-performance, low-noise, and highly reliable power transmission solutions continues to grow, mastering such precise manufacturing techniques for complex components like herringbone gears becomes ever more essential. The integration of this simple yet effective calculation into standard practice represents a meaningful step forward in the art and science of gear manufacturing.