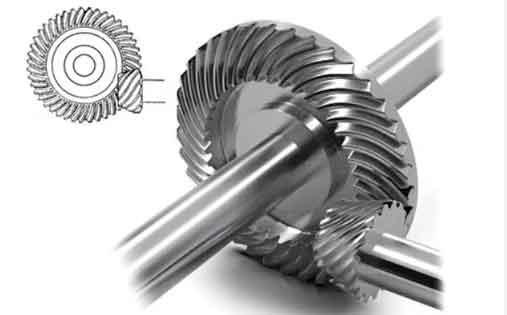

The transmission of motion and power in complex machinery fundamentally relies on precision components, among which gears are paramount. Spiral bevel gears, characterized by their curved teeth and angled axes, offer superior benefits including high load-carrying capacity, smooth and quiet operation, and increased contact ratio. These advantages make them indispensable in demanding sectors such as automotive drivetrains, aerospace propulsion systems, heavy industrial machinery, and robotics. As manufacturing technology advances towards greater precision and efficiency, the requirements for the quality and accuracy of these critical components have become increasingly stringent. Consequently, developing advanced, reliable, and efficient measurement techniques for spiral bevel gears is a crucial endeavor to ensure product performance and longevity.

Traditional measurement methodologies for spiral bevel gears can be broadly categorized into several groups: single-flank rolling composite error testing, single-item geometric error inspection, on-machine measurement, and non-contact measurement. While domestic and international research has led to the development of CNC coordinate-based gear measuring centers and specialized systems, persistent challenges remain. These often include issues with measurement stability, limited functionality and performance, and insufficient accuracy for high-precision applications. Contact-based measurement methods, which use tactile probes, face inherent limitations when inspecting complex curved surfaces like those found on spiral bevel gears. The probe may not reach the tooth root for complete profile data, and extensive, complex pre-measurement path planning is required based on gear parameters, which is computationally burdensome and reduces overall efficiency. Furthermore, probe wear and the need for radius compensation introduce additional sources of potential error. Therefore, the pursuit of a high-efficiency, high-accuracy, and streamlined measurement solution is imperative to overcome the longstanding challenges in spiral bevel gear metrology.

This article presents a comprehensive non-contact measurement methodology for spiral bevel gears utilizing a laser displacement sensor. The core principle involves capturing the three-dimensional coordinates of the gear tooth surface through coordinated motion and optical triangulation. This approach eliminates the need for complex tactile probe path planning and compensation, simplifies the measurement process, and allows for the simultaneous acquisition of data necessary for analyzing multiple error types from a single scan, significantly enhancing measurement throughput and precision. The discussion will encompass the design and working principle of the measurement apparatus, the establishment of a mathematical ideal model for Gleason-system spiral bevel gears, and detailed algorithms for evaluating key geometric deviations such as tooth profile error and pitch deviations.

Principle and Configuration of the Laser-Based Measurement System

Fundamental Working Principle

The measurement system operates on a coordinate measurement principle integrated with optical non-contact sensing. A laser displacement sensor is mounted on a multi-axis motion system. The system controls the relative movement between the sensor and the spiral bevel gear under test. The laser sensor projects a spot onto the gear tooth surface, and the reflected light is captured by the receiver. By combining the known mechanical coordinates of the sensor head (from linear and rotary encoders on the motion axes) with the relative distance value provided by the laser sensor, the three-dimensional coordinates of the sampled points on the tooth surface can be calculated. Through systematic data acquisition over the gear’s surface and subsequent computer analysis comparing the measured data to the ideal geometric model, critical deviations like tooth profile relative error and various pitch errors can be determined efficiently.

System Hardware Composition

The measurement instrument is constructed around a precision mechanical platform featuring three orthogonal linear axes (X, Y, Z) and a rotary axis (C). A high-precision rotary table, serving as the C-axis, carries the workpiece (the spiral bevel gear). The Y-axis stage is mounted on the X-axis stage, providing motion in the horizontal plane. The Z-axis stage is mounted vertically and carries the bracket for the laser displacement sensor. This arrangement allows the sensor to be positioned arbitrarily within the measurement volume. A crucial component is the sensor adjustment apparatus, which consists of two rotational stages allowing the laser displacement sensor to be oriented at various angles. This adjustability is essential for ensuring that the laser beam can be oriented approximately perpendicular to the local tooth surface at the mean cone distance, guaranteeing optimal signal reception and data integrity across the entire curved profile of the spiral bevel gear, regardless of its spiral angle. All linear axes are equipped with linear encoders, and the rotary table incorporates a high-resolution angular encoder, providing closed-loop feedback for precise position control. A computer system runs custom software for motion control, data acquisition, and error analysis.

| Component | Description | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| X, Y, Z Linear Axes | Precision linear motion stages with encoders. | Provide Cartesian positioning of the sensor in 3D space. |

| C-Axis (Rotary Table) | High-precision rotary stage with angular encoder. | Rotates the gear under test for full circumferential scanning. |

| Laser Displacement Sensor | Non-contact optical sensor (e.g., confocal or triangulation type). | Measures the distance from the sensor head to the gear tooth surface. |

| Sensor Adjustment Apparatus | Two-axis rotational mount for the sensor. | Orients the laser beam to be near-perpendicular to the local tooth surface slope. |

| Control & Data Acquisition System | Industrial PC with motion controller and DAQ software. | Coordinates axis movement, records encoder and sensor data, performs analysis. |

Establishing the Ideal Mathematical Model for Spiral Bevel Gears

Accurate measurement and error evaluation require a precise mathematical representation of the ideal gear tooth surface. For Gleason system spiral bevel gears, the tooth surface is generated via a simulated gear shaping process using a hypothetical crown gear (generator) and a rotating cutter head. The following derivation establishes the ideal tooth surface equations based on gear generation theory and coordinate transformations.

Coordinate Systems for Gear Generation

The generation process involves multiple coordinate systems representing the machine, cutter, imaginary crown gear, and workpiece. The relationships between these systems are defined by a series of homogeneous transformation matrices. The primary systems include:

1. Machine Fixed Coordinate System \( S_1(O_1-x_1, y_1, z_1) \): Fixed to the gear generator.

2. Cradle Coordinate System \( S_2(O_2-x_2, y_2, z_2) \): Rotates with the cradle (carrying the imaginary crown gear).

3. Cutter Head Coordinate System \( S_3(O_3-x_3, y_3, z_3) \): Fixed to the rotating cutter head.

4. Workpiece Coordinate System \( S_4(O_4-x_4, y_4, z_4) \): Fixed to the gear blank being cut.

The transformation involves parameters such as machine root angle \(\delta\), cradle angle \(\beta_1\), work rotation angle \(\beta_2\), radial setting \(S\), initial phase angle \(q_0\), and the ratio of roll \(i\).

Mathematical Model of the Cutter Blade Surface

The cutting tool is typically a double-sided cutter head with internal and external blades. The surface of a straight-sided blade is conical. In its local coordinate system \(S_3\), the vector equation for a point on the cutter surface is given by:

$$

\mathbf{r}^{(3)}(u, \theta) = \begin{bmatrix}

(r_{p0} – u \sin \alpha) \cos \theta \\

(r_{p0} – u \sin \alpha) \sin \theta \\

-u \cos \alpha

\end{bmatrix}

$$

Where:

• \(u\) is the distance from the blade’s cutting edge point \(P_0\) to the generic point \(P\) along the cone.

• \(\theta\) is the rotation angle of the cutter head.

• \(r_{p0}\) is the point radius (distance from cutter axis to the blade’s cutting edge). For the inner blade: \(r_{p0} = r_d – w/2, \alpha=\alpha_i\). For the outer blade: \(r_{p0} = r_d + w/2, \alpha=-\alpha_o\).

• \(\alpha\) is the blade pressure angle.

• \(r_d\) is the nominal cutter radius.

• \(w\) is the point width.

Tooth Surface Equation of the Imaginary Crown Gear

Transforming the cutter surface equation to the machine coordinate system \(S_1\) yields the surface of the imaginary crown gear tooth. The position vector \(\mathbf{r}_p\) of the cutting edge point \(P_0\) in \(S_1\) is:

$$

\mathbf{r}_p = \begin{bmatrix}

S \cos q + r_{p0} \sin(q – \theta) \\

S \sin q – r_{p0} \cos(q – \theta) \\

0

\end{bmatrix}

$$

Where \(q = q_0 + \beta_1\) is the current machine phase angle. The unit normal vector \(\mathbf{n}\) and a vector \(\mathbf{t}\) along the blade cone in \(S_1\) are:

$$

\mathbf{n} = \begin{bmatrix}

\cos \alpha \sin(q – \theta) \\

-\cos \alpha \cos(q – \theta) \\

-\sin \alpha

\end{bmatrix}, \quad

\mathbf{t} = \begin{bmatrix}

\sin \alpha \sin(q – \theta) \\

-\sin \alpha \cos(q – \theta) \\

\cos \alpha

\end{bmatrix}

$$

Since \(u = \overline{PP_0}\), the crown gear tooth surface equation in \(S_1\) becomes:

$$

\mathbf{r}^{(1)}(u, \theta, q) = \mathbf{r}_p – u \mathbf{t} = \begin{bmatrix}

S \cos q + r_{p0} \sin(q – \theta) – u \sin \alpha \sin(q – \theta) \\

S \sin q – r_{p0} \cos(q – \theta) + u \sin \alpha \cos(q – \theta) \\

-u \cos \alpha

\end{bmatrix}

$$

Tooth Surface Equation of the Generated Spiral Bevel Gear

The spiral bevel gear tooth surface is the envelope of the crown gear surface during the generating motion. Applying the equation of meshing \( \mathbf{n} \cdot \mathbf{v}^{(12)} = 0 \), where \(\mathbf{v}^{(12)}\) is the relative velocity between the crown gear and the workpiece, solves for the parameter \(u\) as a function of \(q\) and \(\theta\):

$$

u(q, \theta) = -\frac{a \cos \alpha (b + c) + d \sin \alpha \cdot e}{d \cos(q – \theta)}

$$

where:

$$

a = i \sin \delta – 1, \quad b = [S \sin q – r_{p0} \cos(q – \theta)] \sin(q – \theta)

$$

$$

c = [S \cos q + r_{p0} \sin(q – \theta)] \cos(q – \theta), \quad d = i \cos \delta, \quad e = S \sin q – r_{p0} \cos(q – \theta)

$$

Finally, transforming the crown gear surface \(\mathbf{r}^{(1)}\) and its normal \(\mathbf{n}\) to the workpiece coordinate system \(S_4\) via transformation matrices \(\mathbf{M}_{41} = \mathbf{M}_{4f2}\mathbf{M}_{f21}\) yields the final generated spiral bevel gear tooth surface:

$$

\mathbf{r}^{(4)} = \mathbf{M}_{41} \mathbf{r}^{(1)}, \quad \mathbf{n}^{(4)} = \mathbf{L}_{41} \mathbf{n}

$$

where \(\mathbf{L}_{41}\) is the 3×3 rotational submatrix of \(\mathbf{M}_{41}\). The explicit form of \(\mathbf{r}^{(4)}\) is:

$$

\mathbf{r}^{(4)} = \begin{bmatrix}

r_{1x} \cos \delta + r_{1z} \sin \delta \\

r_{1y} \cos[i(q – q_0)] + \sin[i(q – q_0)] (r_{1z} \cos \delta – r_{1x} \sin \delta) \\

-r_{1y} \sin[i(q – q_0)] + \cos[i(q – q_0)] (r_{1z} \cos \delta – r_{1x} \sin \delta)

\end{bmatrix}

$$

Here, \(r_{1x}, r_{1y}, r_{1z}\) are the components of \(\mathbf{r}^{(1)}\). This vector function \(\mathbf{r}^{(4)}(q, \theta)\) defines the ideal tooth flank of the spiral bevel gear.

Tooth Profile Equation at the Mean Cone Distance

According to gear standards (e.g., GB/T 11365, ISO 23509), key deviations like profile and pitch errors are evaluated on the trace located at the mean cone distance. At this point, the gear can be approximated by an equivalent spur gear. The tooth profile on this equivalent gear is a standard involute. The parametric equations for this involute profile in a local Cartesian coordinate system are:

$$

\begin{aligned}

x_p(u_k) &= r_b \sin u_k – r_b u_k \cos u_k \\

y_p(u_k) &= r_b \cos u_k + r_b u_k \sin u_k

\end{aligned}

$$

Where:

• \(u_k = \alpha_k + \theta_k\) is the roll angle.

• \(\alpha_k\) is the pressure angle at the point.

• \(\theta_k\) is the involute roll angle (function of \(\alpha_k\)).

• \(r_b\) is the base radius of the equivalent gear at the mean cone.

The base radius is calculated from gear parameters: number of teeth \(z\), mean module \(m_m\), and pressure angle \(\alpha\). For a spiral bevel gear with outer module \(m_e\), pitch angle \(\delta\), and face width factor \(\phi_R = b/R_e\):

$$

m_m = m_e (1 – \phi_R / 2), \quad z_v = \frac{z}{\cos \delta}, \quad r_b = \frac{m_m z_v \cos \alpha}{2} = \frac{m_e (1 – \phi_R / 2) z \cos \alpha}{2 \cos \delta}

$$

The equation of the normal to the involute at any point \(P(x_p, y_p)\) is:

$$

y = k x + r_b, \quad \text{where } k = \tan\left( \arctan\left(\frac{y_p}{x_p}\right) + \frac{\pi}{2} + \alpha_H \right)

$$

Here, \(\alpha_H\) is the pressure angle at point \(P\). This model serves as the theoretical reference for evaluating tooth profile deviations on spiral bevel gears.

Methodology for Deviation Analysis of Spiral Bevel Gears

Non-Contact Measurement Procedure

The measurement process begins with system setup. The laser sensor’s tilt angle (via the adjustment apparatus) is set approximately equal to the mean spiral angle of the spiral bevel gear. The gear is mounted on the rotary table via a precision mandrel. The system software is initialized with the basic gear parameters. The measurement sequence is automated:

1. The sensor is rotated (around a secondary axis) so the laser beam is perpendicular to the gear’s root cone element.

2. The linear axes position the sensor so the laser spot lies on the plane containing the gear axis.

3. The Y-axis moves the sensor a distance equal to the mean cone radius \(R_m\).

4. The Z-axis positions the sensor at the height corresponding to the midpoint of the face width.

5. The automated measurement command starts. The rotary table (C-axis) rotates the gear at a constant angular velocity while the system simultaneously records the laser sensor distance readings and the corresponding angular positions from the rotary encoder at a fixed sampling rate (e.g., every 100 ms). This continues for one full revolution of the spiral bevel gear.

6. The sensor is retracted, and the acquired cloud of 3D coordinate points is processed for error analysis.

Analysis of Tooth Profile Relative Error (\(\Delta f_c\))

The tooth profile relative error for spiral bevel gears is defined as the maximum difference, along the direction of the tooth profile normal at the evaluation trace, between the actual profile and the design profile within the evaluated range. It is measured as a linear deviation at the mean cone.

The raw measurement provides discrete points \(N_i(x_i, y_i)\) near the evaluation circle. To accurately find the intersection of the actual profile with this circle, a segment of the actual profile is fitted using a cubic polynomial via the least-squares method. For \(n\) selected data points near the evaluation circle, let the fitting curve be \(y = a_0 + a_1x + a_2x^2 + a_3x^3\). The coefficients are found by minimizing the sum of squared errors:

$$

\min \sum_{i=1}^{n} \left[ y_i – (a_0 + a_1x_i + a_2x_i^2 + a_3x_i^3) \right]^2

$$

This leads to the normal equations:

$$

\begin{bmatrix}

n & \sum x_i & \sum x_i^2 & \sum x_i^3 \\

\sum x_i & \sum x_i^2 & \sum x_i^3 & \sum x_i^4 \\

\sum x_i^2 & \sum x_i^3 & \sum x_i^4 & \sum x_i^5 \\

\sum x_i^3 & \sum x_i^4 & \sum x_i^5 & \sum x_i^6

\end{bmatrix}

\begin{bmatrix}

a_0 \\ a_1 \\ a_2 \\ a_3

\end{bmatrix}

=

\begin{bmatrix}

\sum y_i \\ \sum x_i y_i \\ \sum x_i^2 y_i \\ \sum x_i^3 y_i

\end{bmatrix}

$$

Solving this system yields the coefficients and thus the equation of the fitted actual profile curve \(y_{act}(x)\). Its intersection point \(C_i(x_C, y_C)\) with the evaluation circle (radius \(r_m\)) is found numerically.

Next, the theoretical involute profile equation (from the model) is used to find its intersection point \(D_i(x_D, y_D)\) with the same evaluation circle. The normal line to the theoretical profile at \(D_i\) is constructed using the previously described normal equation. The intersection point \(E_i(x_E, y_E)\) of this normal line with the fitted actual curve \(y_{act}(x)\) is calculated. The profile deviation for this tooth \(i\) is the signed distance between points \(D_i\) and \(E_i\) along the normal direction:

$$

\Delta f_{ci} = \pm \sqrt{(x_D – x_E)^2 + (y_D – y_E)^2}

$$

The sign is positive if \(E_i\) lies outside the theoretical profile (excess material) and negative if inside. The tooth profile relative error \(f_c\) for the gear is the range of these deviations across all teeth or as specified by the relevant standard.

Analysis of Pitch Deviations

Pitch deviations are evaluated on the evaluation circle at the mean cone. The single pitch deviation \(f_{pt}\) is the difference between the actual pitch and the theoretical pitch. The cumulative pitch deviation \(F_p\) is the maximum difference between the actual and theoretical positions of tooth flanks over a full revolution.

Using the same fitted curves for each tooth flank, the intersections \(C_i\) with the evaluation circle are determined for all teeth. The actual arc length between the corresponding points on two adjacent teeth \(i\) and \(i+1\) is the actual pitch \(p_{act, i}\):

$$

p_{act, i} = r_m \cdot \Delta \phi_i = r_m \cdot \left| \arctan\left(\frac{y_{C_{i+1}} – y_{C_i}}{x_{C_{i+1}} – x_{C_i}}\right) \right|

$$

where \(r_m\) is the mean cone radius. The theoretical pitch \(p_{th}\) is:

$$

p_{th} = \frac{2\pi r_m}{z} = \pi m_m

$$

The single pitch deviation for the \(i\)-th pitch is:

$$

\Delta f_{pt, i} = p_{act, i} – p_{th}

$$

The cumulative deviation up to the \(k\)-th tooth is the sum of single pitch deviations:

$$

F_{pk} = \sum_{i=1}^{k} \Delta f_{pt, i}

$$

The total cumulative pitch deviation \(F_p\) is the maximum range of \(F_{pk}\) over one revolution:

$$

F_p = \max(F_{pk}) – \min(F_{pk})

$$

This method also allows for the indirect calculation of related parameters like individual tooth thickness and potential backlash.

| Deviation Type | Symbol | Algorithmic Basis | Key Calculation Step |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tooth Profile Relative Error | \(f_c, \Delta f_{ci}\) | Least-squares curve fitting of measured points, intersection with evaluation circle and theoretical normal. | Solve \( \min \sum [y_i – P_3(x_i)]^2 \), find intersection of normal line at theoretical point with fitted actual curve. |

| Single Pitch Deviation | \(f_{pt}\) | Angular difference between adjacent tooth intersection points on the evaluation circle. | \( \Delta f_{pt, i} = r_m \cdot \Delta \phi_i – \pi m_m \). |

| Cumulative Pitch Deviation | \(F_p\) | Running sum of single pitch deviations over all teeth. | \( F_p = \max(\sum_{i=1}^k \Delta f_{pt,i}) – \min(\sum_{i=1}^k \Delta f_{pt,i}) \). |

Measurement Experiment and Results for Spiral Bevel Gears

A practical measurement experiment was conducted to validate the proposed methodology on a pair of Gleason-system spiral bevel gears. The key gear parameters are listed in the table below.

| Parameter | Symbol | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Teeth | \(z_1, z_2\) | 30 | – |

| Outer Module | \(m_e\) | 3.0 | mm |

| Shaft Angle | \(\Sigma\) | 90° | degree |

| Pitch Angle | \(\delta_1, \delta_2\) | 45° | degree |

| Outer Cone Distance | \(R_e\) | 63.64 | mm |

| Face Width | \(b\) | 20.00 | mm |

| Mean Spiral Angle | \(\beta_m\) | 35° | degree |

| Pressure Angle | \(\alpha\) | 20° | degree |

| Face Width Factor | \(\phi_R\) | ~0.314 | – |

The gear was manufactured to a target accuracy grade of IT8. The measurement procedure as described was executed. The laser sensor scanned the tooth flanks, and the collected data was processed using the algorithms for profile and pitch deviation. The resulting deviation plots were generated, and key metrics were extracted.

| Evaluation Item | Symbol | Measured Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average Single Pitch Deviation | \(\bar{f}_{pt}\) | +0.000829 | mm |

| Maximum Single Pitch Deviation | \(f_{pt max}\) | -0.02788 | mm |

| Minimum Single Pitch Deviation | \(f_{pt min}\) | +0.00097 | mm |

| Total Cumulative Pitch Deviation | \(F_p\) | -0.05557 | mm |

| Tooth Profile Relative Error | \(f_c\) | 0.01093 | mm |

The analysis of the deviation curves and the tabulated results shows that all evaluated parameters—single pitch deviation \(f_{pt}\), total cumulative pitch deviation \(F_p\), and tooth profile relative error \(f_c\)—fall within the tolerance limits specified for accuracy grade IT8 according to international standards. This confirms that the measured spiral bevel gear conforms to its intended design grade and validates the effectiveness of the laser-based measurement and analysis system in accurately assessing the geometric quality of spiral bevel gears.

Conclusion

This article has detailed a comprehensive and effective methodology for the precision measurement of spiral bevel gears using a non-contact laser displacement sensor system. The key advantages of this approach over traditional tactile methods are substantial. First, it eliminates the need for complex pre-measurement probe path planning based on the intricate geometry of spiral bevel gears, streamlining the setup process. Second, the non-contact nature avoids issues related to probe wear, stylus force deflection, and the need for probe radius compensation, thereby enhancing measurement reliability and accuracy. Third, a single, continuous data acquisition scan provides a dense point cloud that can be used to evaluate multiple geometric deviations simultaneously, dramatically improving inspection throughput.

The system’s hardware design, featuring a multi-axis motion platform and a crucial laser sensor orientation mechanism, ensures that the measurement beam can be optimally aligned perpendicular to the local tooth surface slope. This is essential for obtaining valid data across the entire curved flank of spiral bevel gears with high spiral angles. The mathematical foundation, deriving the ideal tooth surface equations from basic gear generation principles, provides a rigorous reference model for the spiral bevel gear. The error analysis algorithms, leveraging least-squares curve fitting and geometric intersection calculations, robustly extract critical quality metrics such as tooth profile relative error and pitch deviations from the measured data.

The experimental results on a sample spiral bevel gear demonstrate the system’s practical capability to accurately assess gear quality against standard tolerance grades. This laser-based measurement technology presents a significant advancement in spiral bevel gear metrology, offering a solution that is efficient, accurate, and adaptable to the high-quality demands of modern manufacturing. The principles and methods described are also broadly applicable to the measurement of other complex, sculptured surfaces found in advanced mechanical components.