Abstract

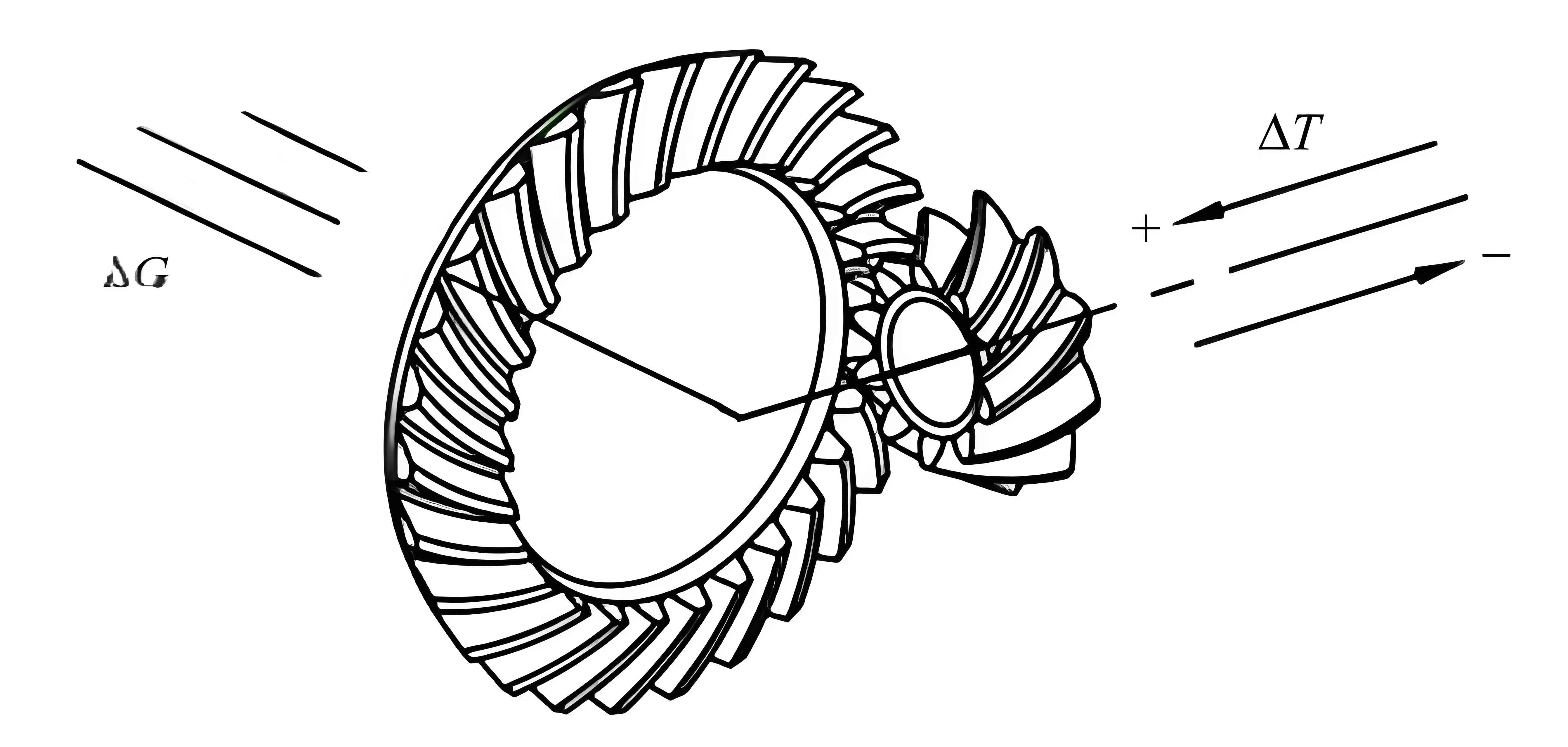

The heavy-duty spiral bevel gear transmission system, employing theories such as gear strength calculation, fatigue cumulative damage, and fracture mechanics. Combined with domestic manufacturing processes and technologies for spiral bevel gears, the fatigue characteristics of these gears are thoroughly examined.

1. Introduction

Heavy-duty spiral bevel gears serve as crucial transmission components in various drivetrains. Due to complex operating conditions, these gears are subjected to alternating loads during actual use, leading to fatigue cracks. These cracks propagate continuously, ultimately causing fatigue failure of the gears. As the contradiction between fatigue issues of spiral bevel gears and the increasing demands for high transmission power and lightweight designs intensifies, predicting the fatigue life of gear teeth has become an indispensable challenge in the development of transmission technology.

2. Research Status of Spiral Bevel Gears

| Period | Key Developments | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1960s | Gleason’s generation and forming methods for spiral bevel gears | Relying heavily on empirical knowledge |

| 1970s | Domestic technology system formed based on Gleason’s technology | In-depth research on tooth surface optimization, meshing characteristics, and contact pattern sensitivity |

| Mid-1980s | Introduction of Free-Form CNC milling and grinding machines by Gleason | Improved precision, rigidity, and adjustment efficiency |

| Present Day | Widespread adoption of Free-Form CNC machines for spiral bevel gear manufacturing | Domestic manufacturing theory is mature, but there is still a gap in precision and efficiency compared to international standards |

3. Manufacturing Processes of Spiral Bevel Gears

3.1 Manufacturing Methods

3.1.1 Milling

Spiral bevel gears consist of a driving gear and a driven gear. The driving gear is milled using the blade tilt method or the deformation method, while the driven gear employs the generative or forming method. Each method requires theoretical calculations to adjust tool and machine parameters. Milling is commonly used for rough machining, leaving a margin for final heat treatment and grinding.

3.1.2 Grinding

Grinding is a precision process, mainly for hard-surfaced gears after final heat treatment. It removes deformation and milling margins, improving tooth surface accuracy to grade 4 or 5. The grinding parameters are derived from complex calculations, considering factors such as grinding burns and cracks.

3.1.3 Contact Pattern Inspection

Inspecting the contact pattern of spiral bevel gears is crucial for simulating their operation. This involves loading a gear pair on a tester, applying colorant to the tooth surfaces, and observing the contact area shape and position under a given load.

3.2 Manufacturing Challenges

- Adjustments for achieving ideal contact patterns.

- Deformation of hard-surfaced gears due to materials, internal stresses, and heat treatment.

- Stress release during processing, causing gear deformation.

- Controlling imbalance for high-speed gears.

3.3 Process Route Design

When designing the process route, consider the overall manufacturing difficulties of spiral bevel gears, such as thin walls, easy deformation, poor machinability, high surface hardness, and meshing pattern sensitivity. Design tool shapes, grinding wheel profiles, deformation compensation fixtures, and low-imbalance process routes based on calculated parameters and deformation laws.

4. Bending Fatigue Life Analysis of Spiral Bevel Gears

Spiral bevel gears are the most critical, complex, and vulnerable components in a transmission system. They operate under dynamic conditions with point contact and localized conjugacy. The working environment is extremely complex, especially for gears operating under high speeds, heavy loads, high temperatures, and weight restrictions.

4.1 Prediction of Crack Initiation Life

Crack initiation life refers to the time from initial crack formation to a significant crack extension under fatigue loads. There is no uniform standard for determining crack initiation; however, common sizes for initial cracks range from 0.05 to 0.50 mm.

According to Dowling’s elastic fracture mechanics formula, the critical crack size typically ranges from 0.1 to 1.0 mm. Zheng Xiulin proposed a fatigue crack initiation life expression based on the local stress-strain method. Fatigue cracks often initiate at the root of notches due to high strain concentrations.

4.2 Prediction of Crack Propagation Life

Crack propagation life involves the stage where the bending fatigue crack extends from its initial size to a critical size. It can be analyzed using linear elastic fracture mechanics theory. Cracks are classified into three types: opening-mode, sliding-mode, and tearing-mode. Among these, opening-mode cracks are the most dangerous and are the primary cause of failure under low stress conditions.

Considering the quantitative effect of surface hardness on fatigue life, the crack propagation rate formula is applied. Various parameters, expressed as functions of hardness, estimate crack growth at different lengths.

5. Contact Fatigue Life Analysis of Spiral Bevel Gears

In addition to bending fatigue, spiral bevel gears experience contact fatigue due to repeated compressive stresses from meshing. Contact fatigue failure is a primary cause of gear failure in heavy-duty transmissions.

5.1 Formation Mechanism and Characteristics of Contact Fatigue Cracks

During operation, high contact stress in the meshing area generates maximum shear stress in the subsurface layer, leading to plastic deformation. With repeated strain cycles, initial cracks form after a certain number of cycles. Cracks then propagate along the subsurface plane towards the gear surface and the core, forming long fatigue pits. The crack propagation rate is hindered by surface hardness.

For heavy-duty spiral bevel gears, processes like carburizing, quenching, and shot peening are used to increase tooth surface hardness. These treatments result in specific characteristics for crack initiation and propagation:

- Initial crack formation occurs below the non-hardened layer with the highest shear stress-to-hardness ratio.

- Cracks form in both directions from the maximum shear stress location.

- Multiple cracks merge, leading to spalling.

5.2 Prediction of Contact Fatigue Crack Initiation Life

The local stress-life curve predicts crack initiation life, assuming a crack length of 30 μm after a specific number of load cycles. The ratio of critical stress to hardness is considered the mechanical criterion for crack initiation. The crack initiation point is assumed to be where the maximum shear stress-to-hardness ratio is highest.

Prediction is based on the Basquin equation, using the equivalent tensile stress at the initiation point. The tensile strength limit is estimated from local hardness, assuming a fatigue limit stress of 700 MPa for high-strength steels above 1400 MPa.

5.3 Prediction of Contact Fatigue Crack Propagation Life

The crack propagation life model depends on accurately predicting the crack initiation point and propagation rate. Microhardness and residual stress are incorporated into the analysis model based on the Paris formula. The Paris formula is revised to account for the influence of local hardness on crack propagation rates, which increase with lower hardness values. By integrating over the range from initial to final crack lengths, the crack propagation life is obtained.

Conclusion

This study examines the fatigue development process of heavy-duty spiral bevel gears, analyzing bending fatigue crack initiation, bending fatigue crack propagation, contact fatigue crack initiation, and contact fatigue crack propagation. By combining these scenarios, a comprehensive contact fatigue life model is derived, considering both crack initiation and propagation lives.

This research provides a comprehensive framework for predicting the fatigue life of heavy-duty spiral bevel gears, essential for the design and development of transmission systems.