In my extensive experience with manufacturing and failure analysis of mechanical components, I have observed that grinding cracks on the tooth surfaces of gear shafts after heat treatment are a prevalent issue leading to premature failure. Gear shafts are indispensable in tractors, automobiles, and various machinery, and their integrity is critical for operational reliability. This article delves into the root causes of grinding cracks in gear shafts and outlines effective preventive strategies, drawing from practical case studies and process improvements. I will emphasize the role of heat treatment and grinding parameters, utilizing formulas and tables to summarize key points, with frequent reference to gear shafts to underscore their importance.

The formation of grinding cracks in gear shafts is fundamentally a stress-induced phenomenon. During grinding, the energy input is predominantly converted into heat, causing a rapid temperature rise in the grinding zone to approximately 1000°C. This generates significant thermal stresses; during heating, compressive stresses prevail, while during cooling, tensile stresses emerge. Cracks occur when the instantaneous tensile stress surpasses the material’s fracture strength. The total stress during grinding is a superposition of thermal, transformational, and deformation stresses. Mathematically, the thermal stress component can be expressed as:

$$\sigma_{th} = \alpha E \Delta T$$

where $\sigma_{th}$ is the thermal stress, $\alpha$ is the coefficient of thermal expansion, $E$ is Young’s modulus, and $\Delta T$ is the temperature gradient. For gear shafts, the maximum tensile stress aligns with the grinding direction, leading to cracks perpendicular to it. The combined stress is:

$$\sigma_{total} = \sigma_{thermal} + \sigma_{transformational} + \sigma_{deformation}$$

where $\sigma_{transformational}$ arises from phase changes and $\sigma_{deformation}$ from plastic deformation. Understanding this interplay is crucial for mitigating cracks in gear shafts.

Heat treatment processes profoundly influence the susceptibility of gear shafts to grinding cracks. The carburizing layer’s properties, including carbon concentration, carbide morphology, retained austenite content, and quenching microstructure, are pivotal. For gear shafts made of alloys like 20CrMnTi steel, optimal parameters must be maintained. Table 1 summarizes the impact of carburizing variables on grinding crack risk for gear shafts.

| Factor | Optimal Range for Gear Shafts | Risk if Deviated | Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surface Carbon Concentration | 0.8%–1.0% | High risk above 1.1%; crack rate up to 80% | Excessive carbides increase brittleness and stress. |

| Carbide Morphology | Fine, uniform distribution | Network distribution raises stress concentration. | Poor dissolution during quenching amplifies stresses. |

| Retained Austenite Content | Below Grade 2 (e.g., <20%) | Higher content increases transformational stress. | Volume changes during cryogenic treatment induce stress. |

| Quenching Microstructure | Cryptocrystalline martensite with minimal austenite | Coarse martensite or excessive austenite elevates stress. | Non-uniform transformation leads to residual stresses. |

The carbon concentration profile in the carburized layer of gear shafts can be modeled as:

$$C(x) = C_s – (C_s – C_0) e^{-x/d}$$

where $C(x)$ is the carbon concentration at depth $x$, $C_s$ is the surface concentration (target 0.8–1.0%), $C_0$ is the core concentration (~0.2% for 20CrMnTi), and $d$ is the diffusion depth. Deviations from this profile, such as a steep gradient, exacerbate stress concentrations. For gear shafts, controlling carbide morphology is vital; networked carbides act as stress raisers, which can be quantified using stress intensity factors: $$K_I = \sigma \sqrt{\pi a}$$ where $K_I$ is the stress intensity, $\sigma$ is applied stress, and $a$ is crack length. In gear shafts, such microcracks propagate under grinding tensile stresses.

Retained austenite in gear shafts contributes to transformational stresses during cooling or cryogenic treatment. The volume change during martensitic transformation is approximated by:

$$\Delta V = \beta \cdot \Delta C$$

where $\Delta V$ is the volume change, $\beta$ is a material constant (~0.01 per 1% carbon for steel), and $\Delta C$ is the carbon content difference. Higher retained austenite in gear shafts leads to greater $\Delta V$ upon transformation, increasing internal stresses. Quenching temperature and time directly affect this; for instance, lowering the quenching temperature from 850°C to 820°C for gear shafts reduces retained austenite from Grade 4-5 to Grade 1-2, as shown in Table 2.

| Quenching Parameter for Gear Shafts | Original Process | Improved Process | Effect on Gear Shafts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature (°C) | 850 | 820 | Reduces retained austenite and thermal stress. |

| Holding Time (minutes) | 30 | 20 | Limits austenite homogenization, minimizing stress. |

| Resulting Surface Hardness (HRC) | 58–62 | 58–62 | Hardness maintained while improving toughness. |

| Retained Austenite Grade | 4–5 | 1–2 | Lower grade decreases transformational stress. |

Cryogenic treatment of gear shafts further influences grinding crack propensity. The process involves cooling to subzero temperatures (e.g., -70°C) to transform retained austenite to martensite, but it introduces additional stresses. The stress relief during tempering is critical; increasing the tempering temperature from 160°C to 180–200°C for gear shafts effectively reduces residual stresses without compromising hardness. The tempering kinetics can be described by the Arrhenius equation for stress relaxation: $$\tau = \tau_0 e^{Q/RT}$$ where $\tau$ is relaxation time, $\tau_0$ is a constant, $Q$ is activation energy, $R$ is gas constant, and $T$ is tempering temperature. Higher $T$ accelerates stress relief in gear shafts. Table 3 compares cryogenic treatment parameters for gear shafts.

| Cryogenic Treatment Parameter for Gear Shafts | Original | Improved | Impact on Gear Shafts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment Temperature (°C) | -70 | -70 | Transforms austenite but adds stress. |

| Tempering Temperature (°C) | 160 | 180–200 | Better stress relief while retaining hardness >58 HRC. |

| Tempering Time (hours) | 2 | 2 | Sufficient for stress dissipation in gear shafts. |

| Residual Stress Reduction | Moderate | Significant | Lower stress minimizes grinding crack risk. |

Grinding processes themselves are a direct contributor to cracks in gear shafts. Factors such as wheel grit, feed rate, cooling, and wheel speed dictate the thermal and mechanical loads. Inadequate cooling or excessive feed rates elevate $\Delta T$ in the grinding zone, raising $\sigma_{th}$ as per the earlier formula. For gear shafts, optimizing these parameters is essential. The specific grinding energy $u$ can be expressed as: $$u = \frac{F_t v_s}{Q_w}$$ where $F_t$ is tangential force, $v_s$ is wheel speed, and $Q_w$ is material removal rate. High $u$ values correlate with increased heat generation and crack risk in gear shafts. Table 4 outlines grinding parameter improvements for gear shafts.

| Grinding Parameter for Gear Shafts | Original | Improved | Rationale for Gear Shafts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wheel Grit Size | 60 (coarse) | 80 (finer) | Sharper cutting edges reduce heat buildup. |

| Cooling Efficiency | Insufficient | Enhanced with wheel slots | Lowers $\Delta T$ and thermal stress. |

| Transverse Feed Rate (mm/pass) | High (e.g., 0.05) | Reduced (e.g., 0.02) | Decreases mechanical and thermal load. |

| Wheel Speed (m/s) | High | Moderate reduction | Lowers grinding energy input. |

| Grinding Stages | Single pass | Roughing + finishing | Distributes stress; finishing removes damaged layer. |

To prevent grinding cracks in gear shafts, I have implemented comprehensive improvements in both heat treatment and grinding. For heat treatment of gear shafts, we ensure a uniform sorbitic microstructure prior to carburizing, with grain size of 5–8 grade and no abnormal structures like Widmanstätten patterns. A small-drop, three-stage gas carburizing process stabilizes surface carbon at 0.8–1.0% for gear shafts, followed by direct air cooling instead of furnace cooling to refine carbide morphology. Two high-temperature tempering cycles at 650°C are used to reduce retained austenite below Grade 2. The quenching temperature for gear shafts is lowered to 820°C with a 20-minute hold, and cryogenic treatment is paired with tempering at 180–200°C. These steps collectively minimize residual stresses in gear shafts, as quantified by the reduction in stress magnitude: $$\Delta \sigma_{residual} \propto \frac{1}{T_{temper}}$$ where higher tempering temperatures $T_{temper}$ yield greater stress relief for gear shafts.

In grinding gear shafts, we adopt a multi-stage approach. The wheel grit is changed to 80 for finer cutting, and cooling is optimized using water-based fluids with additives. The transverse feed is reduced, and wheel speed is adjusted to maintain a specific energy below critical thresholds. The material removal rate $Q_w$ is controlled to avoid excessive heat: $$Q_w = a_p v_w b$$ where $a_p$ is depth of cut, $v_w$ is workpiece speed, and $b$ is width of cut. For gear shafts, limiting $Q_w$ during finishing passes is crucial. Additionally, grinding is split into roughing (high $Q_w$ but with cooling) and finishing (low $Q_w$ for surface integrity). This strategy reduces the net tensile stress on gear shafts during grinding, preventing crack initiation.

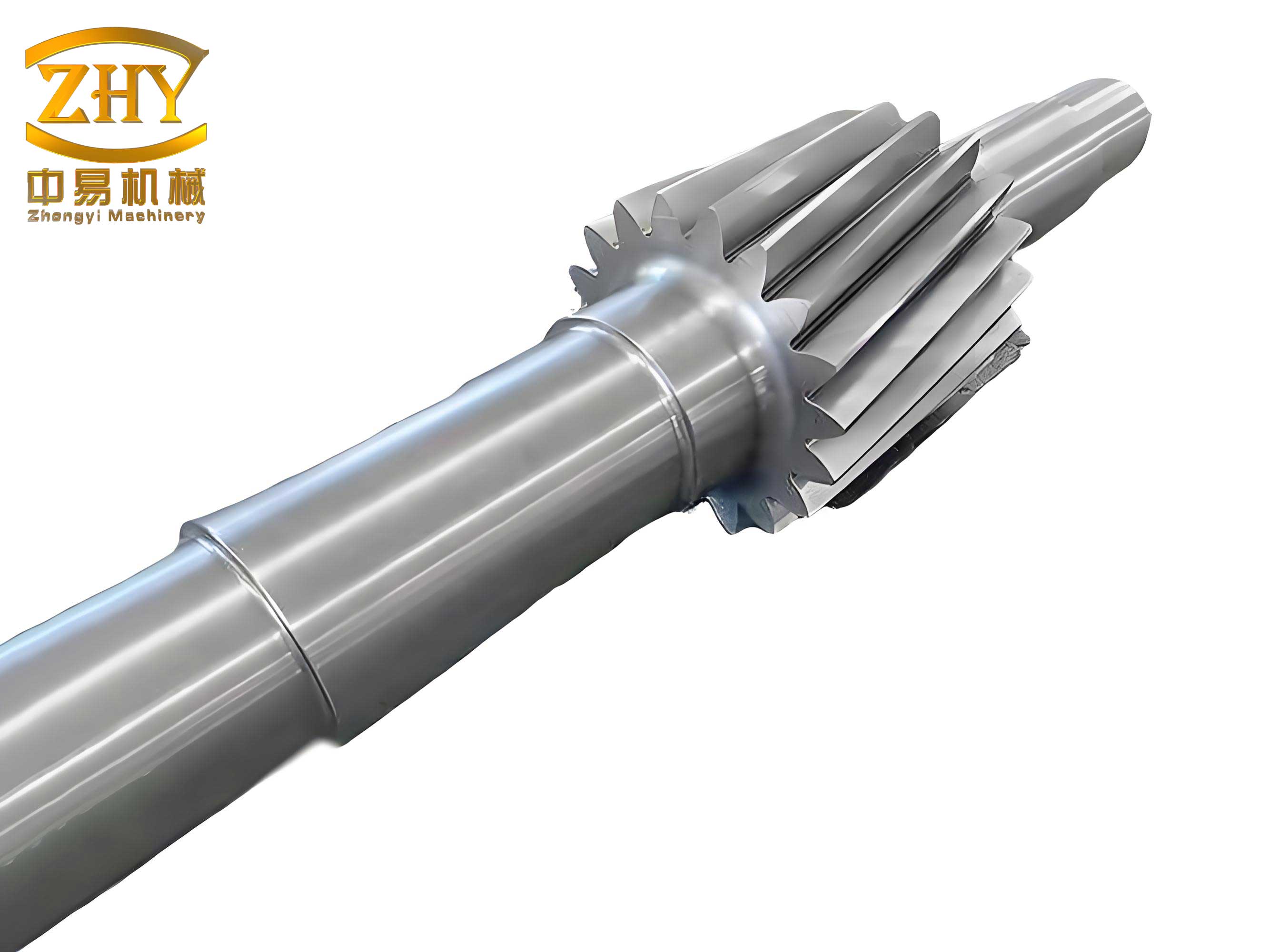

A case study on 20CrMnTi steel gear shafts illustrates these principles. The gear shafts had dimensions: shaft diameter 40 mm, gear outer diameter 100 mm, length 200 mm. The original process led to grinding cracks due to high carbon concentration (1.2%), networked carbides, and insufficient tempering. After implementing the improvements, including carburizing to 0.9% carbon, quenching at 820°C, cryogenic treatment with 180°C tempering, and two-stage grinding with 80-grit wheels, no cracks were detected via magnetic particle inspection. The hardness of the gear shafts remained at 58–62 HRC, meeting performance standards. The success underscores that for gear shafts, a holistic approach addressing both metallurgical and mechanical factors is key.

In conclusion, preventing grinding cracks in gear shafts requires a deep understanding of the interplay between heat treatment-induced stresses and grinding parameters. Through controlled carburizing, optimized quenching and tempering, and careful grinding practices, the risk can be mitigated. Gear shafts treated with these improved protocols exhibit enhanced durability and reliability. Future work could explore advanced modeling of stress distributions in gear shafts using finite element analysis, but the empirical measures discussed here provide a robust foundation for quality assurance in gear shaft manufacturing.