In the field of precision motion control, strain wave gears, also known as harmonic drives, play a pivotal role due to their compact size, high reduction ratios, significant load capacity, and exceptional transmission accuracy. These gears are indispensable in applications ranging from aerospace robotics to industrial automation. However, achieving optimal performance in a strain wave gear heavily relies on the precise control of backlash between the flexspline and circular spline. Insufficient backlash can lead to tooth interference, causing noise, wear, and potential failure, while excessive backlash increases transmission error and hysteresis, degrading positional accuracy. Therefore, designing tooth profiles that ensure minimal and uniformly distributed backlash across the entire meshing cycle is a fundamental challenge in strain wave gear technology. This article presents a comprehensive methodology for the radial modification of the flexspline tooth profile in a strain wave gear, specifically focusing on a triple-arc profile, to achieve spatially uniform backlash distribution and eliminate interference along the axial direction of the cup-shaped flexspline.

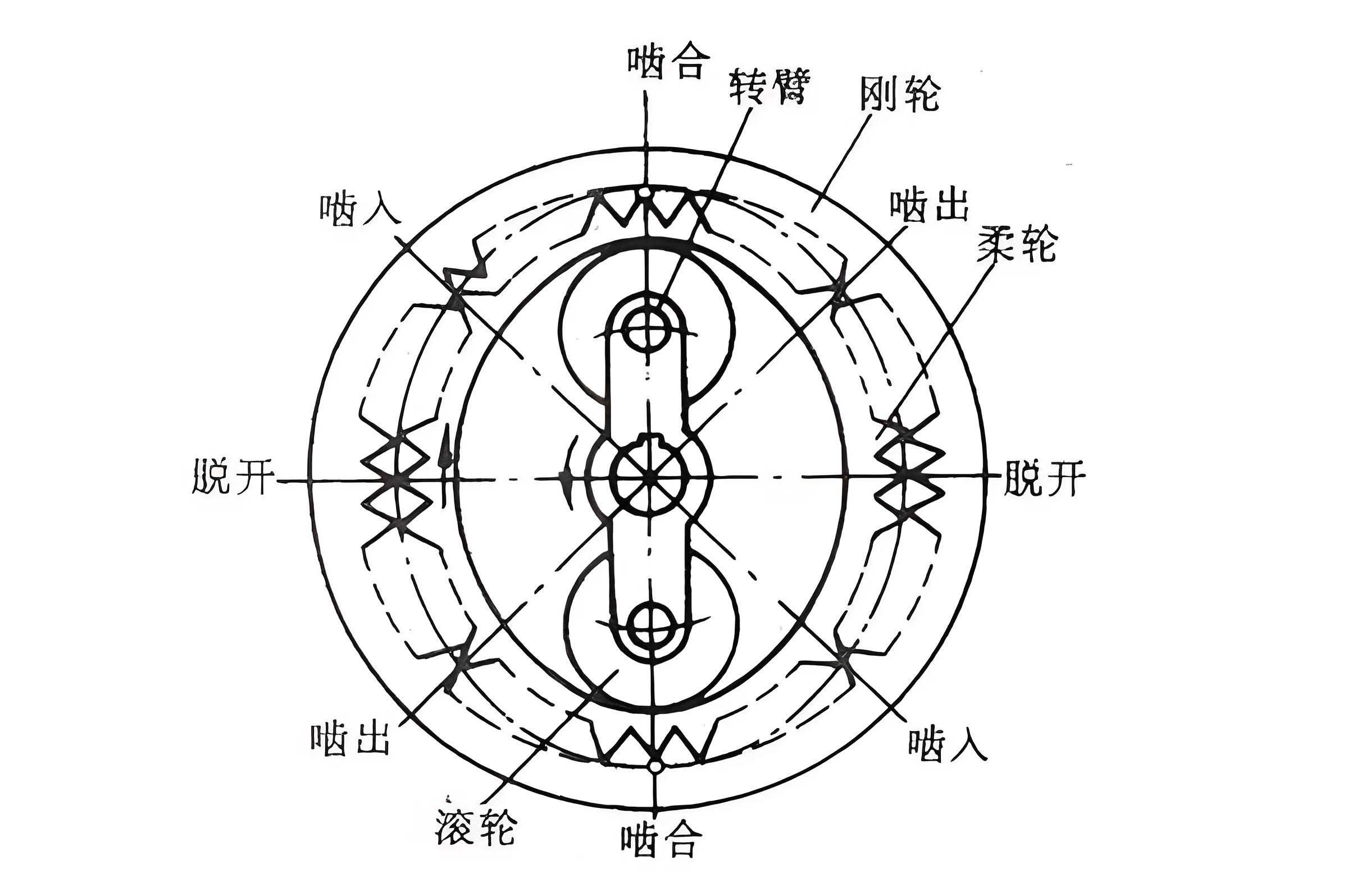

The core principle of a strain wave gear involves an elastic flexspline, a rigid circular spline, and a wave generator. The wave generator, typically an elliptical cam, deforms the flexspline into a non-circular shape, enabling meshing between the flexspline and circular spline at two diametrically opposite regions. As the wave generator rotates, the meshing zones propagate, resulting in slow relative rotation between the splines. A critical aspect often overlooked is the tapered deformation of the cup-shaped flexspline. When the wave generator is inserted, the flexspline does not deform uniformly along its axis; instead, it exhibits a conical deformation where the radial displacement varies linearly from the cup bottom to the front opening. This axial variation means that the meshing condition—defined by the relative position and gap between teeth—differs for each cross-section along the flexspline’s length. If the tooth profiles are designed based solely on a single nominal cross-section, severe interference or excessive backlash can occur at other axial positions, compromising the performance of the strain wave gear.

To address this, I propose a design method that incorporates radial modification of the cutting tool used to manufacture the flexspline. By iteratively adjusting the radial offset of the tool for different axial sections of the flexspline, a three-dimensional tooth surface is generated. This modified spatial tooth profile compensates for the tapered deformation, aiming to achieve near-zero backlash in all cross-sections and promote a favorable line contact meshing state along the tooth face. The foundation of this method lies in an exact algorithm for calculating the assembly deformation of the flexspline and a precise algorithm for computing the circumferential backlash between conjugate arc profiles. The triple-arc tooth profile is chosen for its design flexibility and superior meshing characteristics compared to simpler profiles like the double-arc or involute, making it particularly suitable for high-performance strain wave gear applications.

Mathematical Foundation for Meshing Motion and Backlash Calculation

The kinematic relationship between the deformed flexspline and the circular spline forms the basis for tooth profile design and backlash analysis in a strain wave gear. Consider a coordinate system \(\{O-X_W Y_W\}\) fixed to the wave generator, with its origin at the rotation center and the \(X_W\)-axis aligned with the major axis of the elliptical wave generator. Another coordinate system \(\{O_f-X_f Y_f\}\) is attached to an individual tooth on the flexspline, with \(O_f\) located on the neutral curve of the flexspline and the \(X_f\)-axis aligned with the tooth’s symmetry line (the normal to the neutral curve at \(O_f\)). A third system \(\{O-X_C Y_C\}\) is fixed to the corresponding tooth space on the circular spline, with the \(X_C\)-axis aligned with the symmetry line of the circular spline tooth space.

Under the assumption of an inextensible neutral curve for the flexspline, the relationship between the angular position \(\phi\) of a point on the undeformed neutral circle (radius \(r_m\)) and the angular position \(\phi_1\) of the same point after deformation (with radial distance \(\rho(\phi_1)\) from the center \(O\)) is given by:

$$\phi = \frac{1}{r_m} \int_0^{\phi_1} \sqrt{\rho^2 + \left( \frac{d\rho}{d\phi_1} \right)^2} d\phi_1$$

The angle \(\phi_W\) between the major axis of the wave generator and the symmetry line of the engaging circular spline tooth space is related to \(\phi\) by the gear ratio:

$$\phi_W = \frac{z_1}{z_2} \phi$$

where \(z_1\) and \(z_2\) are the number of teeth on the flexspline and circular spline, respectively. Consequently, the angle \(\theta\) between the position vector of point \(O_f\) and the \(X_C\)-axis is:

$$\theta = \phi_1 – \phi_W = \phi_1 – \frac{z_1}{z_2} \phi$$

Furthermore, the inclination angle \(\theta_{uz}\) of the normal to the flexspline’s neutral curve (i.e., the angle between the tooth symmetry line \(X_f\) and the position vector \(\rho\)) is:

$$\theta_{uz} = -\arctan\left( \frac{d\rho/d\phi_1}{\rho} \right)$$

Thus, the total angle \(\Phi\) between the circular spline’s tooth space symmetry line (\(X_C\)) and the flexspline’s tooth symmetry line (\(X_f\)) is:

$$\Phi = \theta_{uz} + \theta$$

The coordinates of the flexspline tooth reference point \(O_f\) in the circular spline coordinate system \(\{O-X_C Y_C\}\) are therefore:

$$

\begin{cases}

x_{2O1} = \rho \sin \theta \\

y_{2O1} = \rho \cos \theta

\end{cases}

$$

By varying \(\phi_1\) typically from \(0\) to \(\pi/2\), the trajectory of the flexspline tooth relative to the circular spline tooth space is obtained. This trajectory is central to defining conjugate tooth profiles.

Backlash, in the context of a strain wave gear, is defined as the minimum circumferential gap between potentially contacting tooth surfaces of the flexspline and circular spline when no load is applied. For computational simplicity, the meshing point is often assumed to be at the tip of the flexspline tooth. The backlash calculation between two arc profiles involves finding the shortest distance between them and then converting it into a circumferential gap along the pitch circle. For arc profiles, the shortest distance \(d_{\min}\) can fall into one of three geometric scenarios: between two convex arcs, between a line segment and a convex arc, or between two concave arcs. The corresponding circumferential backlash \(j_{\min}\) is then calculated using the geometric relation:

$$j_{\min} = \frac{d_{\min}}{\cos(\alpha_1 + \alpha_2)}$$

where \(\alpha_1\) is the inclination angle of the line segment representing the shortest distance, and \(\alpha_2\) is the angle between the position vector of the point on the flexspline tooth profile (where the shortest distance is measured) and the \(x\)-axis of the circular spline coordinate system. Accurate backlash calculation using this method allows for a detailed assessment of the meshing state across the engagement region.

Tooth Profile Definition and Multi-Section Analysis

The triple-arc tooth profile offers more design parameters and potentially better meshing performance than double-arc profiles for strain wave gears. The flexspline profile is constructed from three circular arcs: a top arc (near the tooth tip), a middle arc, and a bottom arc (near the tooth root), connected by tangent lines. The key parameters defining this profile include the radii of the three arcs (\(\rho_a\), \(\rho_{af}\), \(\rho_f\)), the radial heights of the middle arc relative to the pitch circle (\(h_{la}\), \(h_{lf}\)), the pressure angle at the pitch point (\(\alpha\)), the addendum (\(h_a\)), dedendum (\(h_f\)), and the tooth thickness on the pitch circle (\(s\)). A typical set of parameters for a flexspline with \(z_1=100\) and module \(m=0.506603\,\text{mm}\) is summarized in Table 1.

| Parameter | Symbol | Value (mm) |

|---|---|---|

| Addendum | \(h_a\) | 0.2837 |

| Dedendum | \(h_f\) | 0.3192 |

| Middle Arc Top Height | \(h_{la}\) | 0.2330 |

| Middle Arc Bottom Height | \(h_{lf}\) | 0.0000 |

| Middle Arc Radius | \(\rho_{af}\) | 1.3678 |

| Top Arc Radius | \(\rho_a\) | 0.1317 |

| Bottom Arc Radius | \(\rho_f\) | 2.4317 |

| Tooth Thickness on Pitch Circle | \(s\) | 0.5659 |

The corresponding circular spline tooth profile is designed as the conjugate profile to the flexspline profile at a specific design cross-section. It is also composed of three circular arcs. Its parameters, such as the radii of the arcs (\(\rho_{a2}\), \(\rho_{af2}\), \(\rho_{f2}\)), the coordinates of the arc centers, and the addendum and dedendum circle radii (\(r_{a2}\), \(r_{f2}\)), are derived from the conjugation condition. For a circular spline with \(z_2=102\), a typical parameter set is given in Table 2.

| Parameter | Symbol | Value (mm) |

|---|---|---|

| Addendum Circle Radius | \(r_{a2}\) | 25.2694 |

| Dedendum Circle Radius | \(r_{f2}\) | 26.0766 |

| Top Arc Radius | \(\rho_{a2}\) | 0.61233 |

| Bottom Arc Radius | \(\rho_{f2}\) | 0.7979 |

| Middle Arc Center (x) | \(x_B\) | -1.42843 |

| Middle Arc Center (y) | \(y_B\) | 25.0201 |

| Bottom Arc Center (x) | \(x_K\) | 1.06597 |

| Bottom Arc Center (y) | \(y_K\) | 25.96174 |

The critical challenge arises from the tapered deformation of the cup-shaped flexspline. Based on the assumption of a straight generator line for the cup’s sidewall, the radial position \(\rho(\phi, z)\) of the neutral curve at any axial coordinate \(z\) (measured from the cup bottom) can be expressed as:

$$\rho(\phi, z) = \left( \rho(\phi) – r_m \right) \frac{z}{z_0} + r_m \quad \text{for} \quad 0 < z < l$$

where \(z_0\) is the axial distance from the cup bottom to the design cross-section, \(l\) is the total axial length of the cup, and \(\rho(\phi)\) is the radial deformation in the design cross-section. For an elliptical wave generator, the deformation in the design section is often modeled as:

$$\rho(\phi) = \frac{a b}{\sqrt{a^2 \sin^2\phi + b^2 \cos^2\phi}} \quad (0 \le \phi \le 90^\circ)$$

with the semi-major axis \(a = r_m + w_0\), where \(w_0\) is the maximum radial displacement, and the semi-minor axis \(b\) is determined from the inextensibility condition. The polar angle \(\phi\) is assumed to vary linearly along the axis. This model reveals that each axial cross-section has a different effective neutral curve shape and maximum radial displacement, fundamentally altering the meshing geometry from the design intent if the tooth profile is constant.

To analyze this, I define several evaluation cross-sections along the axis of a flexspline with a total length \(l=26\,\text{mm}\) and a tooth ring width \(b_0=8.5\,\text{mm}\). Let the design cross-section be at the axial location of the柔性轴承 (flexible bearing), denoted as the middle section at \(z_{\text{mid}}=20.435\,\text{mm}\). A front section near the cup opening is defined at \(z_{\text{front}}=25.3\,\text{mm}\), and a rear section is defined at \(z_{\text{rear}}=16.8\,\text{mm}\). Seven equally spaced cross-sections are considered: four from the front section to the middle section (1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th) and three from the middle to the rear section (5th, 6th, 7th), where the 4th section coincides with the design middle section. For each section, the deformed neutral curve radius \(\rho(\phi, z)\) is calculated using the tapered deformation model. The flexspline tooth profile is then positioned relative to the circular spline profile based on the kinematic equations for that specific section’s deformation, and the backlash is computed using the arc-distance algorithm.

Backlash Distribution Without Radial Modification

When the flexspline is manufactured with a constant tooth profile (i.e., no radial modification), and the circular spline profile is designed to be perfectly conjugate in the middle design section (4th section), the backlash distribution across the seven axial sections reveals significant problems. The results are summarized in Table 3 and depicted graphically. In the design middle section (4th), the backlash is very small and uniform across a wide engagement range (from about \(5^\circ\) to \(50^\circ\) of the wave generator’s rotation angle \(\phi_1\)), with values consistently below \(1.2\,\mu\text{m}\). This indicates an excellent theoretical meshing condition at this specific cross-section, suitable for multi-tooth engagement and high load capacity.

| Cross-Section | Axial Position z (mm) | Maximum Radial Displacement (mm) | Backlash Characteristics | Minimum Backlash / Interference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st (Front) | 25.3 | 0.49769 | Severe interference in the right side of major axis | -81 µm at ~2° |

| 2nd | 23.1 | 0.46554 | Significant interference | -54 µm at ~3° |

| 3rd | 20.94 | 0.43339 | Moderate interference | -27 µm at ~4° |

| 4th (Middle) | 20.435 | 0.40199 | Very small, uniform backlash | ~0 µm at 11° & 45° |

| 5th | 19.93 | 0.37795 | Interference in meshing-in region | -17 µm at ~47° |

| 6th | 18.37 | 0.35424 | Increased interference | -34 µm at ~50° |

| 7th (Rear) | 16.8 | 0.33048 | Severe interference in meshing-in region | -98 µm at ~75° |

The backlash distribution curves show that all other sections exhibit varying degrees of negative backlash (i.e., interference). The most severe interference occurs at the frontmost (1st) and rearmost (7th) sections. At the front, around \(\phi_1 \approx 2^\circ\), the interference reaches -81 µm, indicating that the flexspline tooth material protrudes into the circular spline tooth space. At the rear, around \(\phi_1 \approx 75^\circ\), the interference peaks at -98 µm. All curves intersect near \(\phi_1 \approx 22^\circ\) at a point where the backlash is nearly zero for all sections, but this is an exception. The trend is clear: interference decreases from the front sections toward the middle and then increases again toward the rear. This non-uniform spatial backlash distribution is a direct consequence of the tapered deformation not being accounted for in a constant-profile design. Such interference would cause binding, increased friction, and accelerated wear in an actual strain wave gear assembly, severely degrading its performance and lifespan.

Principles and Implementation of Radial Modification

To compensate for the tapered deformation and achieve a uniformly small backlash along the entire tooth length, I propose applying a radial modification to the tool used to cut the flexspline teeth. Conceptually, this involves shifting the cutting tool radially inward by different amounts for different axial zones of the flexspline. This creates a flexspline with a variable tooth thickness and, consequently, a variable neutral line radius along its axis. The relationship is illustrated in Figure 9 (conceptual). If \(\delta_p(z)\) represents the radial reduction in tooth thickness (or wall thickness) at axial position \(z\), compared to the design section, then the effective neutral line radius \(r_p(z)\) at that section becomes:

$$r_p(z) = r_m – \frac{\delta_p(z)}{2}$$

Since the inner diameter of the cup is typically constant, this modification effectively creates a tapered tooth ring where the teeth are “shorter” radially at the front and rear compared to the middle. The goal of the modification design is to find the function \(\delta_p(z)\) that results in backlash approaching zero in all cross-sections.

An iterative design approach is employed. Based on the initial backlash analysis, target radial inward shifts are set for the most problematic front (1st) and rear (7th) sections to eliminate their interference. Using the backlash calculation algorithm as an evaluation function, the modification amounts for intermediate sections are adjusted, often following a linear or piecewise linear taper, until the backlash in every defined cross-section is minimized and nearly uniform. For the case study presented, after several iterations, the optimal radial downward shifts (relative to the middle section’s tooth height) for the seven sections were determined as shown in Table 4.

| Cross-Section | Axial Position z (mm) | Radial Inward Shift (µm) | Resulting Neutral Line Radius \(r_p(z)\) (mm) | Adjusted Max. Radial Disp. (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st (Front) | 25.3 | 81.82 | 24.7328 | 0.49769 |

| 2nd | 23.1 | 54.55 | 24.7460 | 0.46554 |

| 3rd | 20.94 | 27.27 | 24.7601 | 0.43339 |

| 4th (Middle) | 20.435 | 0.00 | 24.7737 | 0.40199 |

| 5th | 19.93 | 16.81 | 24.7653 | 0.37795 |

| 6th | 18.37 | 33.62 | 24.7569 | 0.35424 |

| 7th (Rear) | 16.8 | 50.40 | 24.7485 | 0.33048 |

The backlash distribution after applying this optimal radial modification is shown in Figure 10. The key improvement is that all sections now exhibit near-zero backlash throughout their engagement ranges, with no interference. The specific minimum backlash values are: 0 µm at \(\phi_1 \approx 2^\circ\) for the 1st section, 0.6 µm at \(\phi_1 \approx 4^\circ\) for the 2nd, 1.1 µm at \(\phi_1 \approx 4^\circ\) for the 3rd, 0 µm and 0.4 µm at \(\phi_1 \approx 11^\circ\) and \(45^\circ\) for the 4th (middle), 0.04 µm at \(\phi_1 \approx 47^\circ\) for the 5th, 0.3 µm at \(\phi_1 \approx 50^\circ\) for the 6th, and 0 µm at \(\phi_1 \approx 51^\circ\) for the 7th section. This represents a spatially uniform meshing condition, transforming the contact from a single-point best contact in the middle section to a line contact spanning the entire tooth face from front to rear. This is highly desirable for load distribution and smooth operation in a strain wave gear.

Verification via Meshing Trajectory Simulation

To visually confirm the improved meshing state, I simulated the meshing trajectory for key cross-sections before and after radial modification. The simulation involves plotting the positions of the flexspline tooth profile relative to the fixed circular spline tooth space at successive angular positions of the wave generator.

For the unmodified case, the simulation in the front (1st) section shows the flexspline tooth profile overlapping significantly with the circular spline profile, confirming the severe interference indicated by the negative backlash calculation. Similarly, in the rear (7th) section, the flexspline tooth tip intersects with the circular spline tooth tip during the meshing-in phase. In contrast, the middle (4th) section shows perfect conjugate motion with a consistent small clearance.

After applying the optimal radial modification, the meshing trajectory changes dramatically. In the front (1st) section, the inward shift of 81.82 µm eliminates the overlap. The flexspline tooth now correctly engages with the circular spline tooth root, maintaining a slight clearance throughout the cycle. The engagement occurs over a broader area of the tooth flank, particularly where the flexspline’s top arc interacts with the circular spline’s root arc. In the rear (7th) section, the inward shift of 50.40 µm prevents the tip-to-tip interference during meshing-in. The simulation shows a clean entry with near-zero clearance, promoting smooth engagement. The overall effect is that all axial sections now exhibit meshing trajectories similar in quality to the originally designed middle section, validating the effectiveness of the radial modification strategy for this strain wave gear.

Discussion and Concluding Remarks

The design of tooth profiles for cup-shaped or hat-shaped flexsplines in strain wave gears must explicitly account for the tapered deformation inherent in their assembly. Relying on conjugate theory based on a single nominal cross-section is insufficient, as it leads to spatially non-uniform backlash and severe interference at the front and rear of the tooth engagement zone. The proposed method of radial tool modification provides a practical and effective solution to this problem. By intentionally varying the radial position of the cutting tool along the flexspline’s axis, a three-dimensional tooth surface is generated that compensates for the axial variation in neutral curve deformation.

The iterative design process, guided by precise algorithms for deformation calculation and arc-profile backlash computation, allows for the determination of an optimal modification law—often a simple linear taper—that minimizes backlash in all critical cross-sections. The result is a strain wave gear where the flexspline and circular spline achieve a near-zero clearance line contact along the entire tooth face. This state is highly beneficial for several reasons: it minimizes the potential for binding under load, reduces stress concentrations by distributing contact over a larger area, improves torsional stiffness, and can help mitigate transmission error caused by tooth-to-tooth variations. Furthermore, by deliberately targeting near-zero backlash, the design can accommodate minor manufacturing tolerances without risking interference, thereby improving the robustness and reliability of the strain wave gear assembly.

The use of a triple-arc tooth profile enhances the effectiveness of this method due to its parametric flexibility. The multiple arc segments provide more degrees of freedom to optimize the contact conditions across the modified spatial surface. While this study focused on a linear radial modification, the framework can be extended to nonlinear modification laws if the deformation pattern or performance requirements demand it. Future work could integrate this radial modification strategy with multi-objective optimization of the arc profile parameters themselves (radii, pressure angle, etc.) to simultaneously optimize for spatial backlash uniformity, contact stress, and bending stress in the strain wave gear teeth.

In conclusion, controlling the spatial distribution of backlash is paramount for unlocking the full performance potential of strain wave gears in precision applications. The radial modification design method presented here offers a systematic, analyzable, and manufacturable approach to achieving this goal. It transforms the meshing condition from a point-focused optimal state to a spatially continuous optimal state, ensuring smooth power transmission, high positional accuracy, and extended service life for one of the most critical components in modern robotic and aerospace drive systems. This advancement contributes significantly to the ongoing evolution of strain wave gear technology towards higher performance and greater reliability.