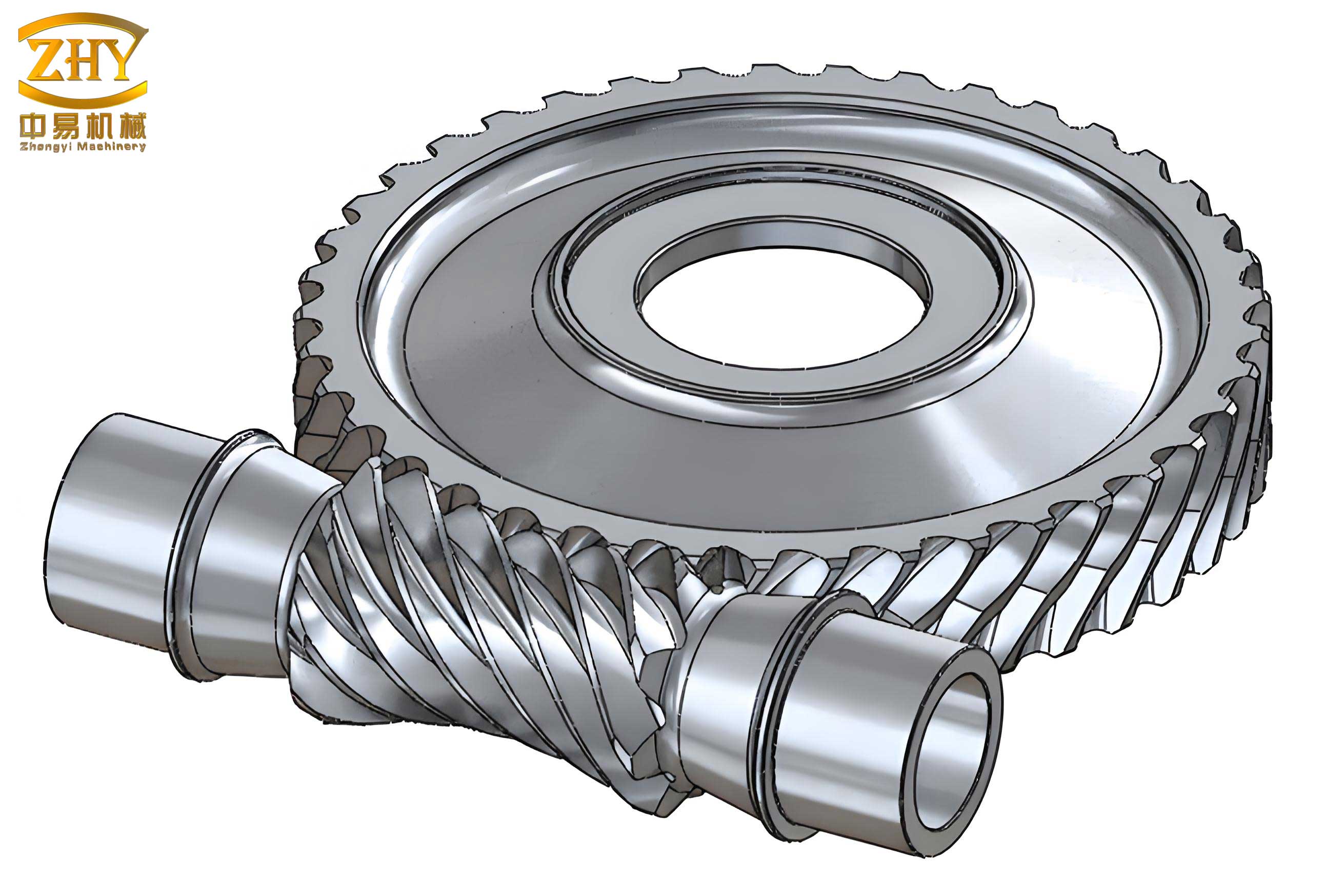

The screw gear drive, commonly known as the worm and worm gear drive, is a fundamental power transmission component prized for its ability to achieve high reduction ratios within a compact envelope, coupled with smooth and quiet operation. This makes it indispensable in applications ranging from heavy-duty industrial machinery to precision positioning systems, such as valve actuators in critical environments. The core of its functionality lies in the complex spatial meshing between the threaded worm and the enveloping gear teeth. Traditional design workflows often rely on standardized gear toolboxes within CAD software or dedicated gear generators. However, these methods can be limiting when dealing with custom or non-standard screw gear geometries, potentially leading to models with improper meshing interfaces that are unsuitable for subsequent high-fidelity engineering analysis. This necessitates a robust, parametric modeling approach that guarantees geometric accuracy from the outset. This article details a comprehensive methodology for the precise 3D modeling of screw gears using CATIA software, followed by an integrated multiphysics analysis loop encompassing Finite Element Analysis (FEA) and Multibody Dynamics Simulation (MBS), culminating in physical validation through machining and testing. The primary objective is to establish a reliable digital prototyping framework that shortens development cycles, reduces prototyping costs, and enhances the performance prediction for screw gear systems.

Parametric Geometric Modeling of Screw Gears in CATIA

The foundation of any accurate engineering analysis is a geometrically precise digital model. For screw gears, this involves creating the worm and the worm gear as separate entities that perfectly conjugate in their meshing action. We begin with a complete set of design parameters, typically derived from initial load and kinematic requirements. The key parameters for our exemplary secondary stage screw gear from a valve actuator reducer are summarized in the table below.

| Parameter | Worm | Worm Gear | Common |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type | ZI (ZI) | Enveloping | – |

| Number of Threads/Teeth | Z1 = 1 | Z2 = 40 | – |

| Normal Module | mn = 1.8 mm | – | |

| Normal Pressure Angle | α_n = 20° | – | |

| Center Distance | a = 46.0 mm | ||

| Reference Diameter | d1 = 20.0 mm | d2 = 72.0 mm | – |

| Tip Diameter | da1 = 23.6 mm | da2 = 78.0 mm | – |

| Root Diameter | df1 = 19.68 mm | df2 = 67.68 mm | – |

| Lead Angle | γ = 5.14° | – | – |

| Face Width | b1 = 25 mm | b2 = 17 mm | – |

| Profile Shift Coefficient | x1 = 0 | x2 = -0.1 | – |

The modeling process is bifurcated for the worm and the worm gear due to their distinct geometries.

Worm Modeling via Helical Sweep

For the ZI-type worm, the axial tooth profile is a straight-sided rack with a pressure angle equal to the normal pressure angle. The 3D worm thread is generated by sweeping this 2D profile along a precise helical path. First, the axial profile is sketched in a plane containing the worm axis, using dimensions calculated from the module, pressure angle, and addendum/dedendum coefficients. The helix is defined by its lead, which is a function of the axial pitch and the number of threads ($$p_z = \pi m_n / \cos\gamma$$, Lead = $$Z_1 \cdot p_z$$). In CATIA, using the “Helix” and “Sweep” commands, the profile is swept along this helix to generate a single thread. This solid thread body is then patterned axially (though for Z1=1, it’s a single thread) and combined with the worm shaft body, which includes features like bearing journals and keyways, to complete the worm model. The geometric integrity of this process ensures the theoretical tooth surface is accurately represented.

Worm Gear Modeling via Envelope Simulation

Modeling the conjugate worm gear is more complex, as its tooth shape is not a simple involute but a surface enveloped by the worm thread during the gear generation process (simulating a hobbling operation). In CATIA, this is efficiently achieved using the Digital Mockup (DMU) Kinematics module. The modeled worm is virtually used as a cutting hob. A kinematic joint (screw joint) is defined between the worm and a blank worm gear body, replicating the exact relative motion of the hobbing process: the worm rotates and translates axially relative to the rotating gear blank. By running this kinematic simulation and using the “Swept Volume” or “Envelope” command, the volume swept by the worm threads is computed. The subtraction of this envelope volume from the gear blank yields the precise tooth spaces of the worm gear. This method directly simulates the manufacturing process, guaranteeing that the generated gear teeth are the exact geometric conjugate of the worm thread, leading to theoretically perfect meshing with minimal backlash when assembled.

Virtual Assembly and Interference Check

The individually created worm and worm gear models are assembled in CATIA’s Assembly Design module with appropriate constraints, typically aligning their axes according to the specified center distance and orienting them correctly. A critical step is the interference and clearance analysis. Using the “Clash” or “Clearance” analysis tool, the assembly is checked for any physical penetration between components. More importantly, the meshing flank clearance can be measured. For our model, the maximum total clearance at the mesh was found to be 0.027 mm. According to international standards like ISO 1328 or GB/T 10089, for a Grade 8 screw gear pair, the allowable single-flank meshing deviation is typically larger than this value (e.g., 0.064 mm), confirming the model’s geometric suitability. This virtual validation step is crucial before committing to analysis or manufacturing.

Finite Element Analysis for Contact Stress Evaluation

With a validated geometric model, the next step is to evaluate its mechanical performance under load using Finite Element Analysis (FEA). The primary concern for screw gears is the contact stress on the tooth flanks, as this drives surface fatigue (pitting) failure. The 3D CATIA model is imported into ANSYS Mechanical for static structural analysis.

| Component | Material | Density (kg/m³) | Young’s Modulus, E (GPa) | Poisson’s Ratio, ν |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Worm | 42CrMo (Alloy Steel) | 7850 | 212 | 0.28 |

| Worm Gear | QAL10-4-4 (Aluminum Bronze) | 7500 | 114 | 0.34 |

The model is appropriately simplified (e.g., small fillets, chamfers may be suppressed) to reduce mesh complexity without affecting contact stress results. The materials are assigned as per Table 2. A fine, curvature-conforming mesh, typically using tetrahedral or hex-dominant elements, is generated with local refinement in the anticipated contact zone. The global element count often exceeds 900,000 to ensure result accuracy. Boundary conditions are applied to simulate a loaded static position: the worm shaft is fully constrained except for a prescribed small rotational displacement (e.g., 5°) around its axis to engage the teeth. The worm gear hub is constrained in all but its rotational degree of freedom, where a resisting torque (T2 = 32 N·m, calculated from input torque and ratio) is applied. A frictional contact pair is defined between the worm thread and worm gear tooth surfaces.

The solved FEA provides the contact stress distribution. For the analyzed screw gear pair, the maximum contact stress was found to be approximately 241 MPa, located near the root area of the worm gear tooth where the relative curvature is highest. This stress value is a key input for evaluating the surface durability of the screw gear design against pitting resistance criteria. The FEA, while powerful, provides a static “snapshot” of the stress at a specific engagement position. To understand the dynamic forces and time-varying stress throughout the mesh cycle, multibody dynamics simulation is employed.

Multibody Dynamics Simulation: From Rigid to Flexible Bodies

Dynamic simulation reveals the time-history of meshing forces, velocities, and accelerations, which are vital for assessing vibration, noise, and dynamic loads. We use ADAMS software, importing the CATIA geometry via a neutral format like STEP or using a direct translator like SimDesigner.

Rigid Body Dynamics Analysis

Initially, both the worm and worm gear are treated as rigid bodies. They are connected to the ground via revolute joints. A rotational motion (velocity) is applied to the worm input shaft. A load torque, applied smoothly using a step function to avoid numerical instability, is placed on the worm gear output shaft. The most critical element is defining the contact force between the gear teeth. ADAMS uses a penalty-based method, often modeling the contact force based on an impact function. A widely used model is based on Hertzian contact theory, where the normal force F_n is a function of the penetration depth δ:

$$F_n = K \delta^{n} + C \frac{d\delta}{dt}$$

Here, K is the contact stiffness, n is the force exponent (typically 1.5 for metallic contact), C is the damping coefficient, and $$d\delta/dt$$ is the penetration velocity. The stiffness K is derived from Hertz theory for two cylinders in contact:

$$K = \frac{4}{3} R^{1/2} E^{*}$$

where the equivalent radius R and equivalent modulus E* are given by:

$$\frac{1}{R} = \frac{1}{R_1} \pm \frac{1}{R_2} \quad \text{(sign depends on curvature)}$$

$$\frac{1}{E^{*}} = \frac{1-\nu_1^2}{E_1} + \frac{1-\nu_2^2}{E_2}$$

For the screw gear pair, R1 and R2 are approximated by the radii of curvature at the pitch point. Using the material properties from Table 2, the contact stiffness K is calculated. Damping C is tuned through iteration to achieve stable, physically reasonable results with minimal numerical energy generation. Friction can be modeled using a Coulomb model. Running the simulation yields the dynamic meshing force. The results typically show an initial impact peak followed by a near-steady fluctuating force. The average meshing force correlates well with the theoretical static force derived from transmitted torque. The fluctuation frequency corresponds to the tooth meshing frequency, which scales linearly with the input speed.

| Worm Speed (r/s) | Avg. Meshing Force, F_avg (N) | Max Meshing Force, F_max (N) | Gear Speed Fluctuation Range (deg/s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.3 | ~622 | ~677 | 11.62 – 11.66 |

| 2.6 | ~622 | ~678 | 23.60 – 23.72 |

| 3.9 | ~622 | ~678 | 35.18 – 35.34 |

Flexible Multibody Dynamics (FMB) / Rigid-Flexible Coupling Analysis

While rigid-body analysis gives forces, it cannot predict component deformation and stress under these dynamic loads. For this, a rigid-flexible coupled analysis is performed. The worm and/or worm gear are converted into flexible bodies. This is done by performing a modal analysis in FEA software (like ANSYS) to extract the component’s natural frequencies and mode shapes. The output is a Modal Neutral File (MNF), which contains information about the flexible body’s mass, stiffness, and mode shapes. This MNF is imported into ADAMS, replacing the rigid geometry. The flexible body interacts with other rigid or flexible bodies through the same joints and forces.

Running the simulation with both screw gear components as flexible bodies provides a more realistic result. The dynamic meshing force history (Table 4) shows similar average values to the rigid analysis but with higher-frequency content due to structural vibrations. More importantly, the stress at any node on the flexible body can be recovered over time. Extracting the stress at the tooth root fillet—a critical location for bending fatigue—over several mesh cycles provides a dynamic stress spectrum. The peak root stress from this dynamic simulation was found to be approximately 229 MPa.

| Analysis Method | Output Metric | Result | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Static FEA (ANSYS) | Max Contact Stress | 241.4 MPa | Static snapshot at loaded position. |

| Rigid MBS (ADAMS) | Avg. Meshing Force | ~622 N | Dynamic force, insensitive to speed. |

| Flexible MBS (ADAMS) | Avg. Meshing Force | ~623 N | Agrees with rigid analysis; includes vibration. |

| Flexible MBS (ADAMS) | Dynamic Root Stress Peak | 228.6 MPa | Time-varying, peak value. |

The close agreement between the static FEA contact stress (241 MPa) and the peak dynamic root stress from the flexible body simulation (229 MPa), with a deviation of only about 5%, serves as a strong cross-validation of both the geometric model and the analysis methodologies. It confirms that the modeling approach captures the essential physics of the screw gear meshing process.

Physical Manufacturing and Experimental Validation

The ultimate validation of any digital design and analysis process is the performance of a physical prototype. The CATIA model, having been vetted through simulation, was used directly for Computer-Aided Manufacturing (CAM). Toolpaths were generated within CATIA’s machining module or a dedicated CAM system, and CNC code was produced to machine the worm from 42CrMo steel and the worm gear from aluminum bronze QAL10-4-4.

The manufactured screw gear pair was subjected to rigorous quality inspection and performance testing. Key steps included:

- Dimensional and Runout Inspection: Critical dimensions and radial runout of the gear were measured. The average radial runout was 0.024 mm, well within the 0.030 mm limit specified for a Grade 8 gear per relevant standards, confirming high manufacturing accuracy.

- Meshing Contact Pattern Test: This is a classic test for gear quality. The worm threads were coated with a thin layer of marking compound (e.g., Prussian blue). The worm was then rotated to drive the gear through several revolutions. The resulting contact pattern on the worm gear teeth was examined. A healthy pattern should be centered on the tooth flank. For this screw gear pair, the contact area covered approximately 70% of the tooth height and 60% of the tooth length, exceeding the minimum requirements (e.g., 55% height, 50% length for Grade 8) and indicating excellent alignment and conjugate geometry from the modeling process.

- Full-Reducer Endurance Test: The screw gear pair was assembled into the complete multi-stage valve actuator reducer. The reducer was mounted on a comprehensive test bench and subjected to prolonged cyclical load testing under lubricated conditions. The test simulated severe operating cycles over an accelerated timeline equivalent to a target service life. After accumulating over 1,200 hours of operation, the reducer was disassembled and inspected. The screw gears showed no signs of abnormal wear, pitting, scuffing, or other fatigue damage. The tooth surfaces remained in excellent condition, confirming the durability predicted by the stress analyses.

| Test | Parameter Measured | Result | Standard/Requirement | Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Runout Inspection | Radial Runout | 0.024 mm (avg) | < 0.030 mm (Grade 8) | Pass |

| Contact Pattern | Area (Height) | ~70% | > 55% | Pass |

| Contact Pattern | Area (Length) | ~60% | > 50% | Pass |

| Endurance Test | Visual Inspection after 1200h | No pitting, spalling, or severe wear | No functional degradation | Pass |

Conclusion

This research demonstrates a complete and effective digital engineering workflow for the design and development of high-performance screw gear drives. The methodology hinges on the creation of a precise, parametrically controlled 3D model using CATIA’s advanced surfacing and kinematic simulation capabilities, which ensures geometric fidelity and correct meshing kinematics from the outset. This accurate digital twin is then seamlessly utilized for multiphysics analysis. Static FEA provides detailed contact and bending stress distributions under load, while multibody dynamics simulation, evolving from rigid-body to more computationally intensive rigid-flexible coupled analysis, reveals the dynamic meshing forces and time-varying stresses. The strong correlation (within 5.3%) between the peak root stress from dynamic flexible-body analysis and the static FEA result provides mutual validation and confidence in the models. Finally, the physical realization and testing of the screw gear pair validated the entire digital process, showing that components manufactured directly from the virtual model met all geometric quality standards and performed reliably under extended endurance testing. This integrated approach—from parametric CATIA modeling through correlated FEA/MBS simulation to physical validation—forms a robust framework that significantly reduces design iteration time, minimizes prototyping costs, and enhances the reliability and performance of screw gear systems for demanding industrial applications. The methodology is particularly valuable for custom or non-standard screw gear designs where off-the-shelf toolboxes are insufficient.