The transmission of motion and power between non-parallel, non-intersecting shafts is a fundamental requirement in countless mechanical systems, from automotive steering mechanisms to industrial conveyor belts and precision instrumentation. Among the various solutions available, screw gears, commonly known as worm and worm wheel drives, stand out for their unique capabilities. These drives offer exceptionally high reduction ratios in a single stage, compact design, smooth and quiet operation due to their sliding meshing action, and a inherent self-locking potential under certain conditions. The effectiveness of a screw gear set hinges on the precise geometry of its conjugate surfaces. However, this very geometry—characterized by complex, spatially curved tooth profiles—presents a significant challenge in the design and verification phase. Traditional two-dimensional drawings often fall short in conveying spatial relationships and identifying potential interferences before physical prototyping.

This is where modern three-dimensional parametric Computer-Aided Design (CAD) and dynamic simulation tools become indispensable. In this exploration, I will detail a streamlined workflow for the rapid 3D modeling and kinematic analysis of screw gears. By leveraging the synergistic power of a mainstream CAD platform and a dedicated gear-creation plugin, we can generate accurate digital twins of the components. Subsequently, integrating these models within a motion simulation environment allows us to virtually assemble, animate, and analyze the drive system. This process validates kinematic principles, checks for interferences, and visualizes performance metrics like velocity and acceleration—all before any metal is cut. The methodology significantly enhances design confidence, accelerates development cycles, and reduces costs associated with physical prototyping and testing.

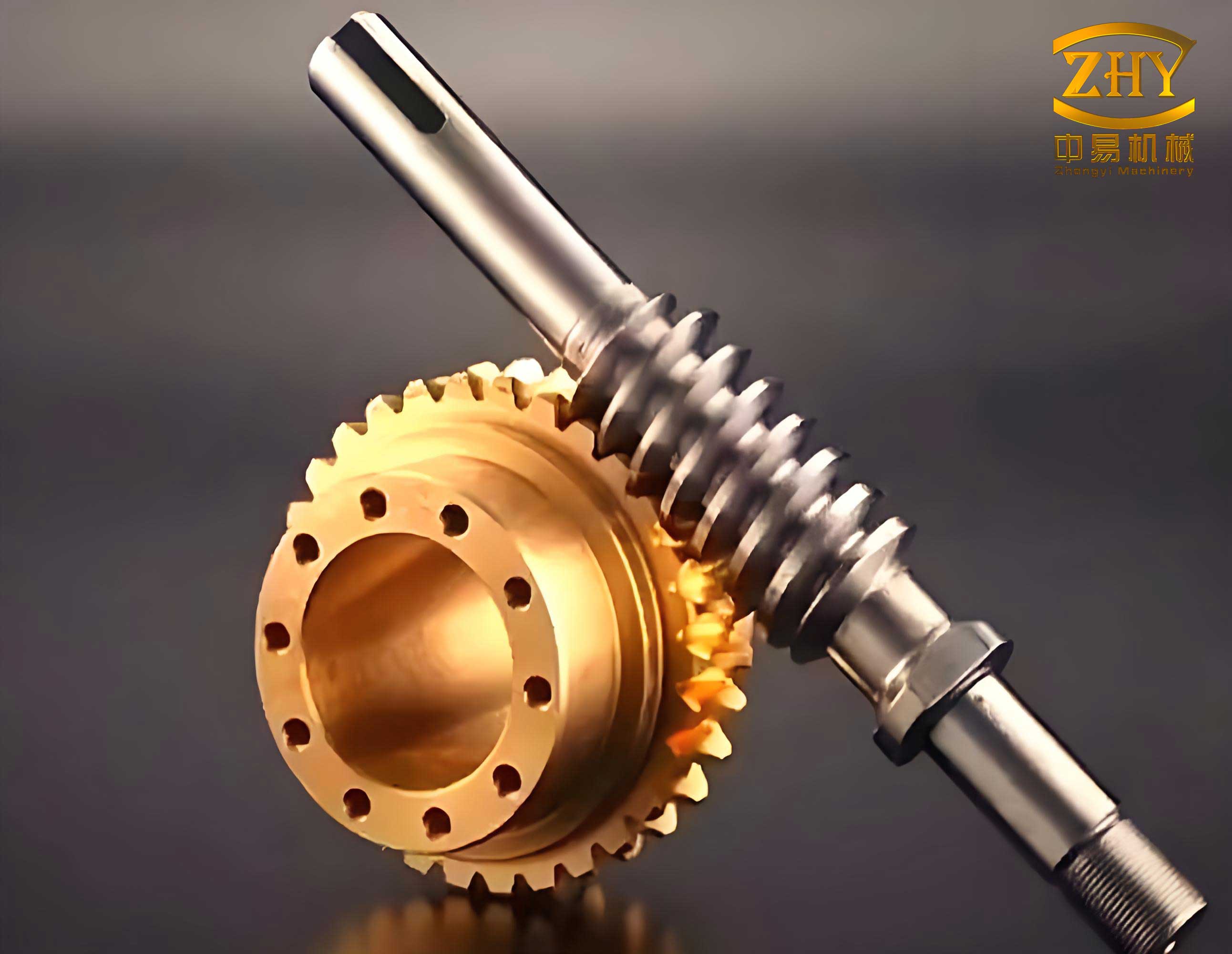

Three-Dimensional Modeling of Screw Gears

The foundation of any credible simulation is an accurate geometric model. Modeling the intricate helicoidal surface of a worm and the matching enveloping surface of a worm wheel from scratch using standard CAD features is a tedious and error-prone process. To achieve both efficiency and precision, I utilize a combination of SolidWorks, a powerful parametric CAD software, and GearTrax, a specialized third-party plugin designed for generating standard and custom gear geometry directly within the SolidWorks environment.

The process begins with defining the key geometric and operational parameters of the screw gear pair. For this case study, I have selected a standard single-enveloping worm gear set with the following primary specifications, summarized in the table below:

| Parameter | Worm (Screw) | Worm Wheel (Gear) |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Threads/Teeth (z) | 1 | 28 |

| Module (m) [mm] | 2 | 2 |

| Pressure Angle (α) [°] | 20 | 20 |

| Lead Angle / Helix Angle (γ, β) [°] | 3.5 | 3.5 |

| Center Distance (a) [mm] | Calculated based on parameters | |

These parameters are fundamental. The module defines the tooth size, the pressure angle affects the force transmission and tooth strength, and matching lead and helix angles are essential for proper meshing. The theoretical center distance \( a \) for a worm gear pair is given by:

$$ a = \frac{m(q + z_2)}{2} $$

where \( q \) is the diametral quotient (worm diameter factor), often related to the lead angle by \( \tan \gamma = z_1 / q \). For our parameters, with \( z_1 = 1 \) and \( \gamma = 3.5^\circ \), \( q \approx 16.35 \), yielding a center distance \( a \approx 44.35 \) mm.

With the parameters defined, the modeling in GearTrax is remarkably straightforward. The procedure follows a logical sequence:

| Step | Action | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Launch GearTrax | Open the plugin from within SolidWorks. |

| 2 | Select Gear Type | Choose the “Worm Gears” module from the interface. |

| 3 | Input Parameters | Enter all values from Table 1 into the corresponding fields in the GearTrax input dialog box. Secondary parameters (e.g., tip and root clearances) are set to standard defaults. |

| 4 | Generate Models | Click the “Finish” or “Create” button. GearTrax automatically processes the inputs, calculates the full tooth geometry, and instantiates two new, fully-defined part documents in SolidWorks: one for the worm and one for the worm wheel. |

The generated models are feature-based and parametric. This means that modifying any key parameter in GearTrax and regenerating the model will update the 3D geometry accordingly, making iterative design exploration highly efficient. The resulting worm model accurately represents the threaded screw with its precise lead angle, while the worm wheel model features the throated, concave tooth profile necessary to envelop the worm properly. The final step in model preparation is virtual assembly. I create a new SolidWorks assembly document, insert the two generated parts, and constrain them using mates that define their operational spatial relationship: the worm axis and wheel axis are set at 90°, the center distance is fixed, and a tangent mate ensures the teeth are in proper contact alignment. This completes the digital prototype of the screw gear system, ready for dynamic analysis.

Kinematic Simulation and Analysis

With an accurate 3D assembly of the screw gears, we can now move beyond static geometry and investigate its dynamic behavior. SolidWorks provides an integrated motion analysis tool, often called Motion Study or Simulation, which is powered by the ADAMS solver engine. This tool allows us to define physical interactions, apply drivers, and simulate the mechanism’s motion over time.

The simulation setup involves defining the components and their interactions logically. First, we establish the ground (fixed) reference frame, typically the housing or base that holds the bearings. Next, we define the kinematic joints or mates. In our assembly, the worm is connected to the ground via a revolute (or hinge) joint, allowing only rotation about its central axis. Similarly, the worm wheel is connected to the ground via its own revolute joint. The meshing contact between the worm threads and the wheel teeth is defined as a 3D contact condition. This contact definition calculates forces based on geometry and material properties, but for a pure kinematic analysis focusing on motion transfer, a simpler gear mate can be used. A gear mate directly enforces a specific speed ratio between two rotating components. The gear ratio \( i \) for a screw gear set is:

$$ i = \frac{\omega_{worm}}{\omega_{wheel}} = \frac{z_2}{z_1} $$

where \( \omega \) represents angular velocity. For our set with \( z_1=1 \) and \( z_2=28 \), the theoretical ratio is \( i = 28 \). This means the worm wheel rotates 28 times slower than the worm.

The driver for the simulation is applied to the worm, defining it as the input component. I apply a rotary motor to the worm’s axis of rotation. For this analysis, I set the motor to provide a constant angular velocity. The input speed is defined as:

$$ n_{input} = 100 \text{ rpm} $$

Converting this to angular velocity in radians per second, which is the standard SI unit often used internally by solvers:

$$ \omega_{input} = \frac{2 \pi \times n_{input}}{60} = \frac{2 \pi \times 100}{60} \approx 10.47 \ \text{rad/s} $$

The simulation is then set to run for a sufficient duration (e.g., several seconds) to capture multiple revolutions of the worm wheel.

| Element | Component | Type/Value |

|---|---|---|

| Ground | Assembly Housing/Bearings | Fixed Geometry |

| Joint 1 | Worm to Ground | Revolute Joint (Rotation about axis) |

| Joint 2 | Worm Wheel to Ground | Revolute Joint (Rotation about axis) |

| Kinematic Constraint | Worm to Worm Wheel | Gear Mate (Ratio = 28:1) |

| Driver | Worm Axis | Rotary Motor (Constant Speed: 10.47 rad/s) |

| Analysis Type | Kinematic (Ignores inertial forces) | |

Upon running the simulation, the software calculates the position, velocity, and acceleration of every component at each time step. The results can be visualized as an animation, providing an immediate check for smooth operation and interference. More quantitatively, we can plot graphs of key performance metrics. The most critical plots are the angular velocity of the input worm and the output worm wheel, and the angular acceleration of the worm wheel.

The theoretical output speed of the worm wheel is calculated as follows:

$$ n_{output} = \frac{n_{input}}{i} = \frac{100 \text{ rpm}}{28} \approx 3.571 \text{ rpm} $$

In angular velocity terms:

$$ \omega_{output} = \frac{\omega_{input}}{i} = \frac{10.47 \text{ rad/s}}{28} \approx 0.3739 \ \text{rad/s} $$

The simulation results are exported and plotted. The graph for the worm’s angular velocity shows a constant line at \( 10.47 \ \text{rad/s} \), confirming the constant input condition. The graph for the worm wheel’s angular velocity shows a constant line at \( 0.374 \ \text{rad/s} \), which matches the theoretical calculation perfectly. The ratio of the two values is exactly 28, validating the fundamental kinematic principle of the screw gear drive.

Furthermore, since the input angular velocity is constant, the theoretical angular acceleration of the output wheel should be zero (\( \alpha = d\omega/dt \)). The simulation plot for the worm wheel’s angular acceleration confirms this, showing a value fluctuating around zero (with minor numerical noise inherent to the solver). This consistency between theoretical prediction and simulation output is crucial. It verifies that the 3D models are geometrically correct, the assembly constraints are properly applied, and the motion simulation is accurately representing the system’s kinematics. Beyond these basic checks, the simulation environment allows for advanced analyses like interference detection throughout the entire motion cycle, ensuring the teeth do not clash, and force estimation if material properties and friction are defined, providing insight into mechanical efficiency and loading.

Conclusion

The integration of specialized modeling tools like GearTrax with comprehensive CAD and CAE platforms such as SolidWorks provides a formidable methodology for the design and analysis of complex mechanical components like screw gears. This approach transforms a traditionally challenging modeling task into a rapid, parameter-driven process. By inputting basic design parameters, a fully detailed and geometrically accurate 3D model of both the worm and worm wheel is generated automatically, eliminating manual modeling errors and saving considerable time.

Subsequent kinematic simulation within the same software ecosystem allows for immediate validation of the design. The motion analysis confirms critical functional characteristics: the achieved speed reduction ratio matches the theoretical design intent, the motion is smooth without discontinuities, and the components operate without interference. The ability to visualize velocity and acceleration plots provides clear, quantitative verification that goes far beyond what static drawings or mental visualization can offer. For the designer, this workflow significantly de-risks the development process. Potential issues can be identified and rectified in the digital domain, long before committing to expensive manufacturing. It facilitates optimization, allowing for quick “what-if” scenarios by simply changing parameters in GearTrax and re-running the simulation. Ultimately, this digital prototyping capability for screw gears and similar complex mechanisms leads to more reliable, better-performing, and faster-to-market mechanical designs.