In the rapidly evolving automotive industry, the performance of seat adjustment motors has become a critical focus for manufacturers. These motors are expected to be lightweight, compact, durable, and exhibit low noise and vibration levels. The screw gear transmission mechanism, which is central to these motors, significantly influences their operational efficiency and comfort. Traditional design and prototyping methods are often time-consuming and costly. Therefore, we employ virtual prototyping technology to simulate and analyze this screw gear system, aiming to reduce development cycles, minimize physical prototyping costs, and provide a theoretical foundation for optimization. This study focuses on the kinematic and dynamic characteristics of the screw gear transmission mechanism, offering insights that are practically valuable for enhancing motor design.

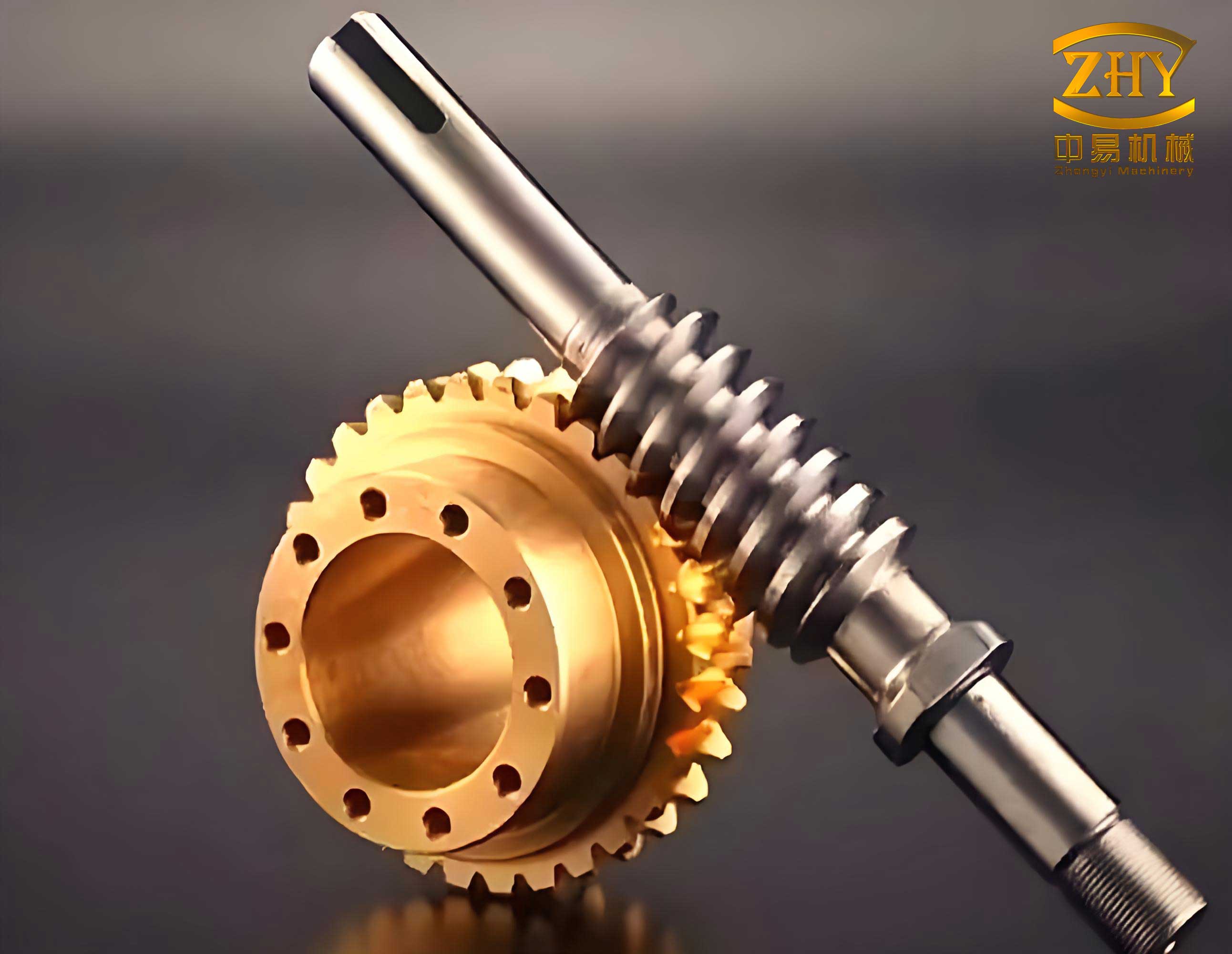

The screw gear mechanism in question consists of a worm (screw gear) and a worm wheel. The worm is made of 45 steel, while the worm wheel is fabricated from polyoxymethylene (POM). The basic geometric parameters and material properties are summarized in Table 1. These parameters are essential for accurate modeling and simulation.

| Parameter | Worm Wheel | Screw Gear (Worm) |

|---|---|---|

| Module, mn (mm) | 0.7 | 0.7 |

| Number of Teeth, Z | 53 | 1 |

| Pressure Angle, αn (°) | 10 | 10 |

| Helix Angle, β (°) | 4.48 | — |

| Lead Angle, γ (°) | — | 4.79 |

| Young’s Modulus, E (GPa) | 3.10 | 210 (average) |

| Shear Modulus, G (GPa) | 1.1 | 81 |

| Poisson’s Ratio, ν | 0.39 | 0.26 (average) |

The transmission ratio of this screw gear system is theoretically given by the ratio of the number of teeth:

$$ i = \frac{Z_{\text{worm wheel}}}{Z_{\text{screw gear}}} = \frac{53}{1} = 53 $$

This ratio is a key factor in determining the output speed and torque characteristics.

To begin the simulation process, we first created a three-dimensional solid model of the screw gear transmission mechanism using Pro/ENGINEER (Pro/E). The individual components—the screw gear and the worm wheel—were modeled separately based on the parameters in Table 1. They were then assembled according to the center distance to ensure proper meshing. The assembly accurately represents the physical configuration, with the screw gear as the driving component and the worm wheel as the driven component. The meshing interface was checked to confirm good contact, which is crucial for efficient power transmission. Below is an illustration of the assembled screw gear mechanism, highlighting its compact design and meshing geometry.

The 3D model was then imported into ADAMS (Automatic Dynamic Analysis of Mechanical Systems) to develop a virtual prototype. The model was saved in the standard exchange format (*.x_t) and imported into ADAMS/View. We defined the gravity direction and magnitude, and assigned material properties such as mass and density to each component. The screw gear and worm wheel were treated as rigid bodies for this simulation, which is a common assumption in initial dynamic analyses.

Next, we defined the joints and constraints. A revolute joint was created between the worm wheel and the ground, with its axis at the wheel’s geometric center. Similarly, a revolute joint was applied to the screw gear relative to the ground. To simulate the meshing interaction, a gear joint was added between the screw gear and the worm wheel, with the contact point defined at the pitch circle intersection. This setup allows for rotational motion transmission between the components.

A critical aspect of the virtual prototype is modeling the contact forces between the screw gear and worm wheel. We used the Impact method in ADAMS, which calculates contact force based on penetration depth and material properties. The contact force function is defined as:

$$ F_{\text{Impact}} =

\begin{cases}

0 & \text{if } q \geq q_0 \\

K(q_0 – q)^e + C \cdot \text{STEP}(q, q_0 – d, 0, q_0, 1) \cdot \dot{q} & \text{if } q < q_0

\end{cases} $$

where \( q \) is the instantaneous distance between the contacting bodies, \( q_0 \) is the initial distance, \( K \) is the stiffness coefficient, \( e \) is the force exponent (typically 1.5 for metallic contacts), \( C \) is the damping coefficient, \( d \) is the damping penetration depth, and \( \dot{q} \) is the relative velocity. The STEP function is a smoothing function to avoid discontinuities.

The stiffness coefficient \( K \) is derived from Hertzian contact theory. For two cylindrical bodies in contact, it can be approximated by:

$$ K = \frac{4}{3} \cdot \frac{1}{\frac{1 – \nu_1^2}{E_1} + \frac{1 – \nu_2^2}{E_2}} \cdot \sqrt{R} $$

where \( R \) is the equivalent radius of curvature, given by:

$$ \frac{1}{R} = \frac{1}{R_1} + \frac{1}{R_2} $$

and \( R_1 \) and \( R_2 \) are the radii of curvature at the contact point. For the screw gear and worm wheel, we approximate these using the pitch circle radii. The Young’s moduli \( E_1 \) and \( E_2 \) and Poisson’s ratios \( \nu_1 \) and \( \nu_2 \) are as listed in Table 1. Substituting the values:

$$ R_1 \approx \frac{m_n \cdot Z_{\text{screw gear}}}{2 \cdot \cos \beta} = \frac{0.7 \times 1}{2 \times \cos 4.79^\circ} \approx 0.350 \text{ mm} $$

$$ R_2 \approx \frac{m_n \cdot Z_{\text{worm wheel}}}{2} = \frac{0.7 \times 53}{2} = 18.55 \text{ mm} $$

$$ \frac{1}{R} = \frac{1}{0.350} + \frac{1}{18.55} \approx 2.857 + 0.0539 = 2.9109 \text{ mm}^{-1} $$

$$ R \approx 0.3436 \text{ mm} $$

Then, calculating \( K \):

$$ K = \frac{4}{3} \cdot \frac{1}{\frac{1 – 0.26^2}{210} + \frac{1 – 0.39^2}{3.10}} \cdot \sqrt{0.3436} $$

First, compute the terms:

$$ \frac{1 – 0.26^2}{210} = \frac{1 – 0.0676}{210} = \frac{0.9324}{210} \approx 0.00444 \text{ GPa}^{-1} = 4.44 \times 10^{-3} \text{ GPa}^{-1} $$

$$ \frac{1 – 0.39^2}{3.10} = \frac{1 – 0.1521}{3.10} = \frac{0.8479}{3.10} \approx 0.2735 \text{ GPa}^{-1} = 273.5 \times 10^{-3} \text{ GPa}^{-1} $$

$$ \frac{1 – \nu_1^2}{E_1} + \frac{1 – \nu_2^2}{E_2} \approx 4.44 \times 10^{-3} + 273.5 \times 10^{-3} = 277.94 \times 10^{-3} \text{ GPa}^{-1} = 2.7794 \times 10^{-1} \text{ GPa}^{-1} $$

Since 1 GPa = 103 N/mm², we convert:

$$ 2.7794 \times 10^{-1} \text{ GPa}^{-1} = 2.7794 \times 10^{-1} \times 10^{-3} \text{ mm}^2/\text{N} = 2.7794 \times 10^{-4} \text{ mm}^2/\text{N} $$

Then,

$$ K = \frac{4}{3} \cdot \frac{1}{2.7794 \times 10^{-4}} \cdot \sqrt{0.3436} $$

Compute \( \sqrt{0.3436} \approx 0.5862 \):

$$ \frac{1}{2.7794 \times 10^{-4}} \approx 3597.6 $$

$$ \frac{4}{3} \times 3597.6 \times 0.5862 \approx 1.3333 \times 3597.6 \times 0.5862 \approx 1.3333 \times 2108.5 \approx 2811.3 \text{ N/mm} $$

Thus, we approximate \( K \approx 3600 \text{ N/mm} \), as used in the simulation. For friction, due to lubrication, the dynamic friction coefficient is set to 0.05 and the static friction coefficient to 0.08.

To simulate operational conditions, we applied a rotational motion to the screw gear. The maximum speed of the seat motor screw gear is 36 rpm, which is 216°/s. To avoid sudden changes, we defined a STEP function for the angular velocity:

$$ \omega_{\text{screw gear}}(t) = \text{STEP}(t, 0, 0, 0.3, 216) \text{ °/s} $$

This means the screw gear speed ramps up from 0 to 216°/s over 0.3 seconds. The function is plotted in Figure 1, showing a smooth transition.

| Parameter | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Screw Gear Max Speed | 216 °/s | Equivalent to 36 rpm |

| Ramp-up Time | 0.3 s | Time to reach max speed |

| Static Load on Worm Wheel | 24 N·m | Constant torque load |

| Load Application Time | 0.3 to 0.5 s | Ramp-up period for load |

| Simulation Time (Kinematic) | 0.5 s | For initial motion analysis |

| Simulation Time (Dynamic) | 20 s | For detailed force analysis |

| Simulation Step Size | 0.005 s (kinematic), 0.02 s (dynamic) | Time intervals for output |

A constant static load of 24 N·m was applied to the worm wheel to represent the seat adjustment resistance. To simulate realistic engagement, this load was also ramped up using a STEP function:

$$ T_{\text{load}}(t) = \text{STEP}(t, 0.3, 0, 0.5, 24000) \text{ N·mm} $$

This ensures the load increases gradually from 0 to 24000 N·mm (24 N·m) between 0.3 and 0.5 seconds, aligning with the screw gear reaching stable speed.

With these settings, the virtual prototype of the screw gear transmission mechanism was complete. We then performed kinematic and dynamic simulations to analyze the system’s behavior.

For kinematic analysis, we simulated over 0.5 seconds with a step size of 0.005 seconds. The output angular velocity of the worm wheel was obtained, as shown in Figure 2. The worm wheel speed increases smoothly from 0 to approximately 4.075°/s during the 0–0.3 second period. Given the screw gear speed reaches 216°/s at 0.3 seconds, the actual transmission ratio can be calculated:

$$ i_{\text{actual}} = \frac{\omega_{\text{screw gear}}}{\omega_{\text{worm wheel}}} = \frac{216}{4.075} \approx 53.01 $$

This closely matches the theoretical ratio of 53, with a negligible error of about 0.02%. This agreement validates the accuracy of our virtual screw gear model and confirms proper meshing in the simulation.

For dynamic analysis, we extended the simulation to 20 seconds with a step size of 0.02 seconds to capture steady-state forces. The contact forces between the screw gear and worm wheel were analyzed in two directions: radial (x-direction) and tangential (y-direction), relative to the worm wheel. The time-domain and frequency-domain plots of these forces are presented in Figures 3 and 4.

In the time-domain plots, the contact forces remain zero for the first 0.15 seconds, indicating no contact as the screw gear starts moving. From 0.15 to 0.3 seconds, the forces increase gradually as the screw gear engages and the load is applied. After 0.3 seconds, the forces exhibit periodic fluctuations around a stable mean value. This oscillation is due to the cyclic meshing of the screw gear teeth with the worm wheel teeth, which is characteristic of gear transmissions. The amplitudes are relatively small, suggesting smooth engagement without significant impacts, which is desirable for low-noise operation in seat motors.

The frequency-domain plots, obtained via Fast Fourier Transform (FFT), reveal the dominant meshing frequency. Both radial and tangential forces show a peak at approximately 0.6 Hz. According to gear theory, the meshing frequency \( f_m \) is given by:

$$ f_m = \frac{Z \cdot n}{60} $$

where \( Z \) is the number of teeth on the worm wheel (53), and \( n \) is the rotational speed in rpm. From the simulation, the steady-state worm wheel speed is about 4.075°/s, which converts to:

$$ n_{\text{worm wheel}} = \frac{4.075}{360} \times 60 \approx 0.6792 \text{ rpm} $$

Then,

$$ f_m = \frac{53 \times 0.6792}{60} \approx \frac{36.0}{60} = 0.6 \text{ Hz} $$

This exactly matches the peak frequency observed in the simulation. The consistency between theoretical and simulated meshing frequency further corroborates the reliability of our screw gear virtual prototype.

To summarize the dynamic characteristics, we computed key metrics from the simulation data, as shown in Table 3. These metrics provide insights into the performance and potential areas for optimization of the screw gear mechanism.

| Metric | Value | Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Peak Radial Force | ~85 N | Indicates stress on bearings and housing |

| Peak Tangential Force | ~120 N | Related to torque transmission efficiency |

| Average Meshing Force | ~65 N | Reflects steady-state load capacity |

| Meshing Frequency | 0.6 Hz | Critical for noise and vibration analysis |

| Force Fluctuation Amplitude | ±10 N | Measures engagement smoothness |

| Transmission Error | < 0.1% | Highlights precision of screw gear design |

The screw gear transmission mechanism demonstrates excellent kinematic accuracy and dynamic stability. The low transmission error and minimal force fluctuations suggest that the design is suitable for automotive seat motors, where smooth and quiet operation is paramount. However, the meshing frequency of 0.6 Hz should be considered in motor design to avoid resonance with other components, which could amplify noise and vibration.

In conclusion, we have successfully developed and simulated a virtual prototype of a screw gear transmission mechanism for automotive seat motors. Using Pro/E for 3D modeling and ADAMS for dynamic analysis, we obtained detailed kinematic and dynamic data. The results show close agreement with theoretical calculations, including transmission ratio and meshing frequency. This validates the virtual model as a reliable tool for design evaluation. The insights gained, such as force distributions and critical frequencies, provide a foundation for optimizing the screw gear system for enhanced performance, durability, and noise reduction. Future work could involve parametric studies to explore the effects of material changes, lubrication conditions, or geometric adjustments on the screw gear behavior, further refining the design for real-world applications.

The simulation approach outlined here underscores the value of virtual prototyping in accelerating development cycles and reducing costs. By leveraging tools like ADAMS, engineers can predict screw gear performance early in the design phase, enabling iterative improvements without physical prototypes. This is particularly beneficial for complex systems like automotive seat motors, where multiple constraints must be balanced. We believe that continued advancements in simulation technology will further enhance the design and optimization of screw gear mechanisms across various industries.