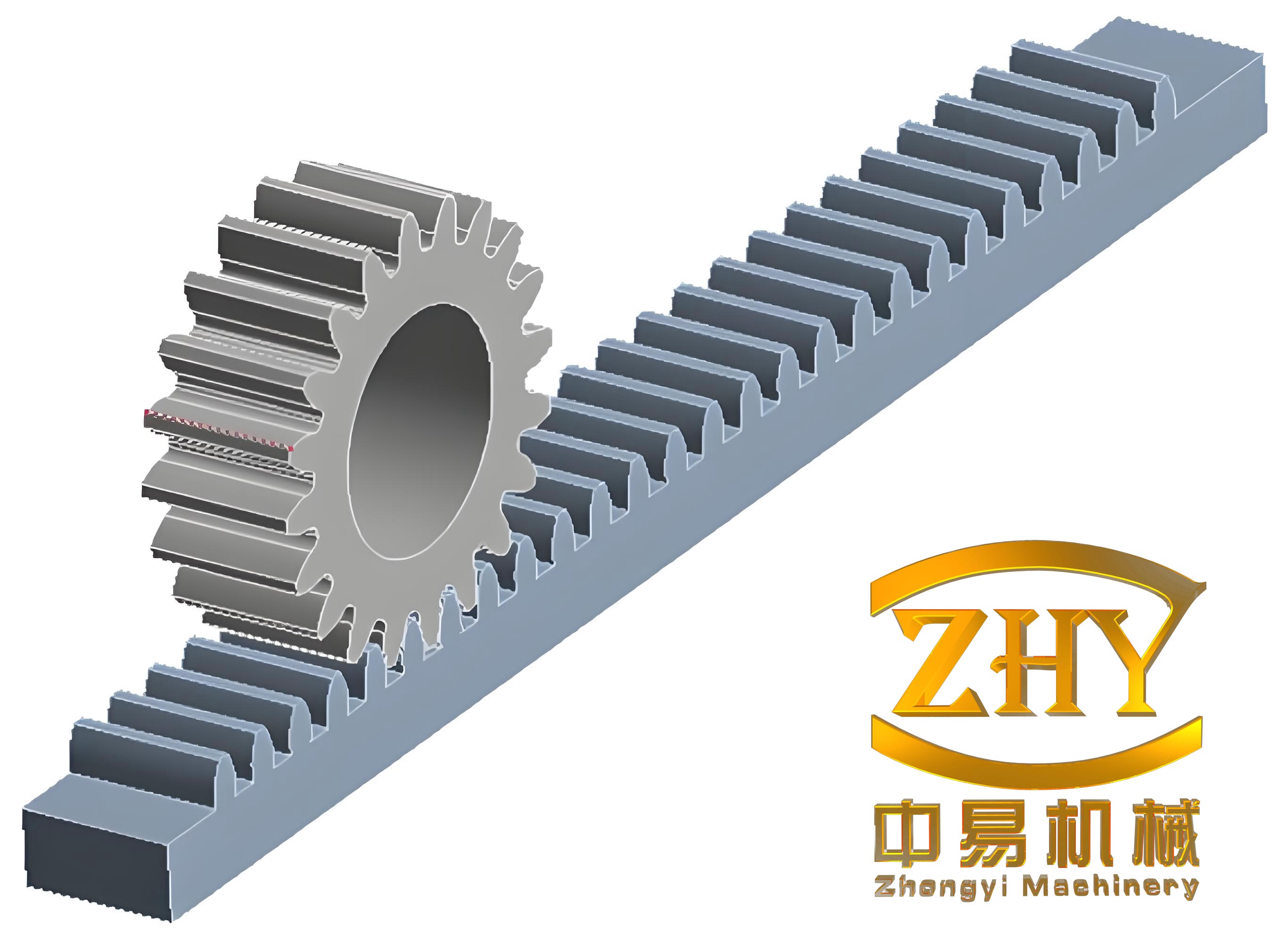

In the field of industrial machinery, reciprocating pumps have been widely utilized for decades, particularly in sectors like oil drilling and extraction. However, traditional reciprocating pumps, especially those based on crank-slider mechanisms, face significant limitations such as short strokes, high operational speeds, and short lifespans of wearing parts like pistons, valves, and seals. These drawbacks restrict their efficiency and durability in demanding applications. To address these issues, I propose a novel composite mechanism that integrates a rack and pinion system with a conventional crank connecting rod. This innovation replaces the standard crosshead with a straight-tooth cylindrical gear, engaging with both a fixed upper rack and a movable lower rack to achieve long-stroke reciprocating motion for the piston. In this article, I will detail the working principles, derive the kinematic equations, perform dynamic simulations, analyze flow characteristics, and evaluate the fatigue life of critical components, focusing on the rack and pinion gear system. The goal is to demonstrate how this rack and pinion mechanism can double the stroke length without increasing the crank radius, thereby reducing operational speed and extending the service life of vulnerable parts.

The core of this research lies in the rack and pinion gear arrangement, which transforms the linear motion derived from the crank mechanism into an amplified piston displacement. Typically, in a traditional reciprocating pump, the crank connecting rod drives a crosshead that directly moves the piston, resulting in a stroke limited by the crank radius. By incorporating a rack and pinion system, the piston’s displacement becomes the sum of the translational movement of the gear’s center and the additional distance covered due to the gear’s rotation along the racks. This rack and pinion setup not only enhances the stroke but also maintains smooth motion transitions, crucial for reducing wear and tear. Throughout this study, I will emphasize the role of the rack and pinion gear in achieving these improvements, using mathematical models and simulations to validate the design.

To understand the motion characteristics of the piston in this rack and pinion combined mechanism, I start by deriving the kinematic equations. For a standard crank connecting rod, the displacement of the crosshead (replaced by the gear in this case) can be expressed based on the crank angle. Let \( r \) denote the crank radius, \( l \) the length of the connecting rod, \( \phi \) the crank angle (where \( \phi = \omega t \) for constant angular velocity \( \omega \)), and \( \beta \) the swing angle of the connecting rod. The displacement \( S_C \) of the gear center is given by:

$$ S_C = r(1 + \cos \phi) – l(1 – \cos \beta) $$

From geometric relationships, \( \cos \beta = \sqrt{1 – \left( \frac{r \sin \phi}{l} \right)^2} \). Substituting this into the equation and simplifying using the binomial expansion, ignoring higher-order terms, yields the approximate displacement formula:

$$ S_C = r \left( 1 + \cos \phi – \frac{\lambda}{2} \sin^2 \phi \right) $$

where \( \lambda = r / l \) is the ratio of crank radius to connecting rod length. The velocity \( v_C \) and acceleration \( a_C \) of the gear center are obtained by differentiating with respect to time:

$$ v_C = -r \omega \left( \sin \phi + \frac{\lambda}{2} \sin 2\phi \right) $$

$$ a_C = -r \omega^2 \left( \cos \phi + \lambda \cos 2\phi \right) $$

In the rack and pinion mechanism, the piston is attached to the lower rack, so its displacement \( S \) is the sum of the gear center displacement \( S_C \) and the distance the rack moves relative to the gear due to rotation. Since the gear rotates as it translates, the relative velocity at the pitch line equals the translational velocity, leading to \( v = 2 v_C \). Integrating and differentiating this, the piston’s motion equations become:

$$ S = 2r \left( 1 + \cos \phi – \frac{\lambda}{2} \sin^2 \phi \right) $$

$$ v = -2r \omega \left( \sin \phi + \frac{\lambda}{2} \sin 2\phi \right) $$

$$ a = -2r \omega^2 \left( \cos \phi + \lambda \cos 2\phi \right) $$

These equations show that the rack and pinion gear system doubles the displacement, velocity, and acceleration compared to a traditional pump with the same crank radius. This means that for a given power input, the stroke length increases by 100%, allowing for lower operational speeds and reduced fatigue on components. The rack and pinion arrangement thus plays a pivotal role in enhancing performance without mechanical complexity.

To validate these theoretical insights, I conducted a rigid-body dynamics simulation using Recurdyn software for a three-cylinder reciprocating pump equipped with this rack and pinion mechanism. The pump parameters are summarized in the table below, highlighting key specifications for both traditional and new designs.

| Parameter | Traditional Pump | New Pump with Rack and Pinion |

|---|---|---|

| Input Power (kW) | 1491 | 1491 |

| Crank Radius (mm) | 100 | 100 |

| Operational Speed (strokes/min) | 120 | 60 |

| Maximum Discharge Pressure (MPa) | 51.7 | 51.7 |

| Piston Stroke (mm) | 200 | 400 |

The simulation model included components such as the frame, high-speed shaft, crankshaft, connecting rods, rack and pinion gear assembly, lower rack-piston rod assembly, and hydraulic end. Joints and contacts were defined, with gear interactions modeled using Hertz contact theory to compute stiffness accurately. A step function controlled the drive motor’s startup, accelerating the crankshaft to a steady 60 rpm, and a load equivalent to the discharge pressure was applied during the discharge phase. The results for piston displacement, velocity, and acceleration over a 2-second simulation are plotted and analyzed.

The displacement curve confirmed a stroke of 400 mm, aligning with theoretical predictions, and exhibited smooth, continuous motion. The velocity profile showed peaks comparable to those of a traditional pump at 120 strokes/min, but with an average reduction in speed due to the lower operational frequency. Acceleration peaks were halved, indicating lower inertial forces and reduced stress on components. Notably, the rack and pinion gear introduced minor vibrations during gear meshing, particularly at motion reversals, but these did not compromise overall stability. The velocity-time graph for all three pistons demonstrated phased motion, essential for balanced flow in multi-cylinder pumps.

Next, I analyzed the flow characteristics of the three-cylinder pump. The instantaneous flow rate for a single cylinder is given by \( q_v = A v_i \) when \( v_i \geq 0 \) (during discharge), and zero during suction, where \( A \) is the piston area and \( v_i \) is the instantaneous velocity. Using the derived velocity equation, I computed the flow rates for each cylinder and superimposed them to obtain the total flow. The flow pulsation rate \( \delta_q \) was calculated as:

$$ \delta_q = \frac{q_{v,\text{max}} – q_{v,\text{min}}}{q_{v,\text{aver}}} $$

where \( q_{v,\text{max}} \), \( q_{v,\text{min}} \), and \( q_{v,\text{aver}} \) are the maximum, minimum, and average flow rates, respectively. The results indicated a pulsation rate of approximately 18.4%, similar to traditional three-cylinder pumps. However, the frequency of pulsations was reduced by half due to the lower stroke rate, meaning fewer reversals per minute. This reduction in flow fluctuation frequency decreases the cycling of pump valves, potentially extending their lifespan. The table below summarizes key flow parameters for the rack and pinion based pump.

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Maximum Instantaneous Flow (m³/s) | 0.15 |

| Minimum Instantaneous Flow (m³/s) | 0.12 |

| Average Flow (m³/s) | 0.135 |

| Pulsation Rate (%) | 18.4 |

| Pulsation Frequency (Hz) | 1 |

Fatigue life analysis of the rack and pinion gear is critical, as gears are prone to failure under cyclic loading. In this mechanism, the十字齿轮 (cross gear) engages with both racks during operation, experiencing varying stresses. I focused on the discharge phase, where the piston force \( F_T = P_d A_0 \) is applied, with \( P_d \) as the discharge pressure and \( A_0 \) the piston area. The gear forces include tangential components \( F_{t1} \) and \( F_{t2} \) from the upper and lower racks, and radial components \( F_{r1} \) and \( F_{r2} \). For equilibrium, \( F_{t1} = F_{t2} = F_T / 2 \) per gear, given the symmetric design. The gear parameters are listed in the following table.

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Module (mm) | 14 |

| Number of Teeth | 32 |

| Pressure Angle (degrees) | 20 |

| Face Width (mm) | 120 |

| Material | 20Cr2Ni4A Steel |

| Surface Hardness | >58 HRC |

Transient dynamics simulation revealed stress distributions, with maximum von Mises stress reaching 567.8 MPa at the tooth root during peak loading, primarily due to stress concentration at the fillet. Stress-time histories for four engaged teeth showed decreasing stresses from the first to the fourth tooth, influenced by acceleration profiles. For fatigue assessment, I used the Basquin equation to model the S-N curve for 20Cr2Ni4A steel, which has a tensile strength of 1483 MPa and yield strength of 1292 MPa. The fatigue life \( N \) in cycles is given by:

$$ N = \frac{1}{2} \left( \frac{\sigma_a}{S’_f} \right)^{1/b} $$

where \( \sigma_a \) is the stress amplitude, \( S’_f = 2122 \) MPa is the fatigue strength coefficient, and \( b = -0.077 \) is the fatigue strength exponent. Corrections for size, surface quality, reliability, and stress concentration were applied using factors \( C_s \), \( C_f \), \( C_r \), and \( k_f \), respectively, leading to the corrected stress \( S_a \):

$$ S_a = \frac{\sigma_a C_s C_f C_r}{k_f} $$

The Morrow model was used for mean stress correction, resulting in the adjusted S-N curve. Fatigue analysis in Recurdyn, considering one crankshaft revolution as a cycle, showed the minimum fatigue life of \( 4.79 \times 10^7 \) cycles, equivalent to 13,316 hours at 60 rpm. This exceeds the 10,000-hour benchmark, indicating the rack and pinion gear’s durability. However, critical areas were identified at the tooth roots, particularly at transition regions, suggesting potential improvements through fillet optimization or increased face width.

In conclusion, the rack and pinion combined crank connecting rod mechanism effectively addresses the limitations of traditional reciprocating pumps by doubling the stroke length without increasing the crank radius. This rack and pinion system reduces operational speed, lowers acceleration peaks, and decreases flow pulsation frequency, all of which contribute to extended component life. The dynamics simulations and fatigue analysis confirm the feasibility of this design, with the rack and pinion gear demonstrating sufficient fatigue resistance for long-term use. Future work could focus on optimizing gear geometry and conducting experimental validations to further enhance the rack and pinion mechanism’s performance in industrial applications.