In the field of petroleum machinery, particularly in pumping unit applications, the demand for robust and efficient gear systems is paramount. As oil fields enter middle and late stages of extraction, the need for long-stroke, low-frequency pumping units to handle viscous and extra-viscous crude oil becomes critical. However, operational conditions often lead to significant load disparities between the upstroke and downstroke, resulting in imbalance and, frequently, over-torque during the downstroke. This over-torque phenomenon poses a severe challenge to the reducers used in these units, leading to premature failures and downtime. In our experience with manufacturing pumping units, several instances of reducer over-torque were observed, prompting a search for solutions that avoid major structural modifications. Traditional approaches, such as upgrading to larger reducers, involve changes to the base, beam, and connecting rod structures, which are impractical for retrofitting existing equipment. Instead, we turned to an innovative concept: the staggered tooth configuration in double-circular-arc herringbone gears. This technology, which we refer to as “staggered tooth,” offers a simple yet effective means to enhance load capacity without altering the reducer’s footprint. In this article, we delve into the mechanics of staggered tooth herringbone gears, analyze their meshing characteristics, and demonstrate through theoretical and practical examples how they can significantly improve the performance of pumping unit reducers.

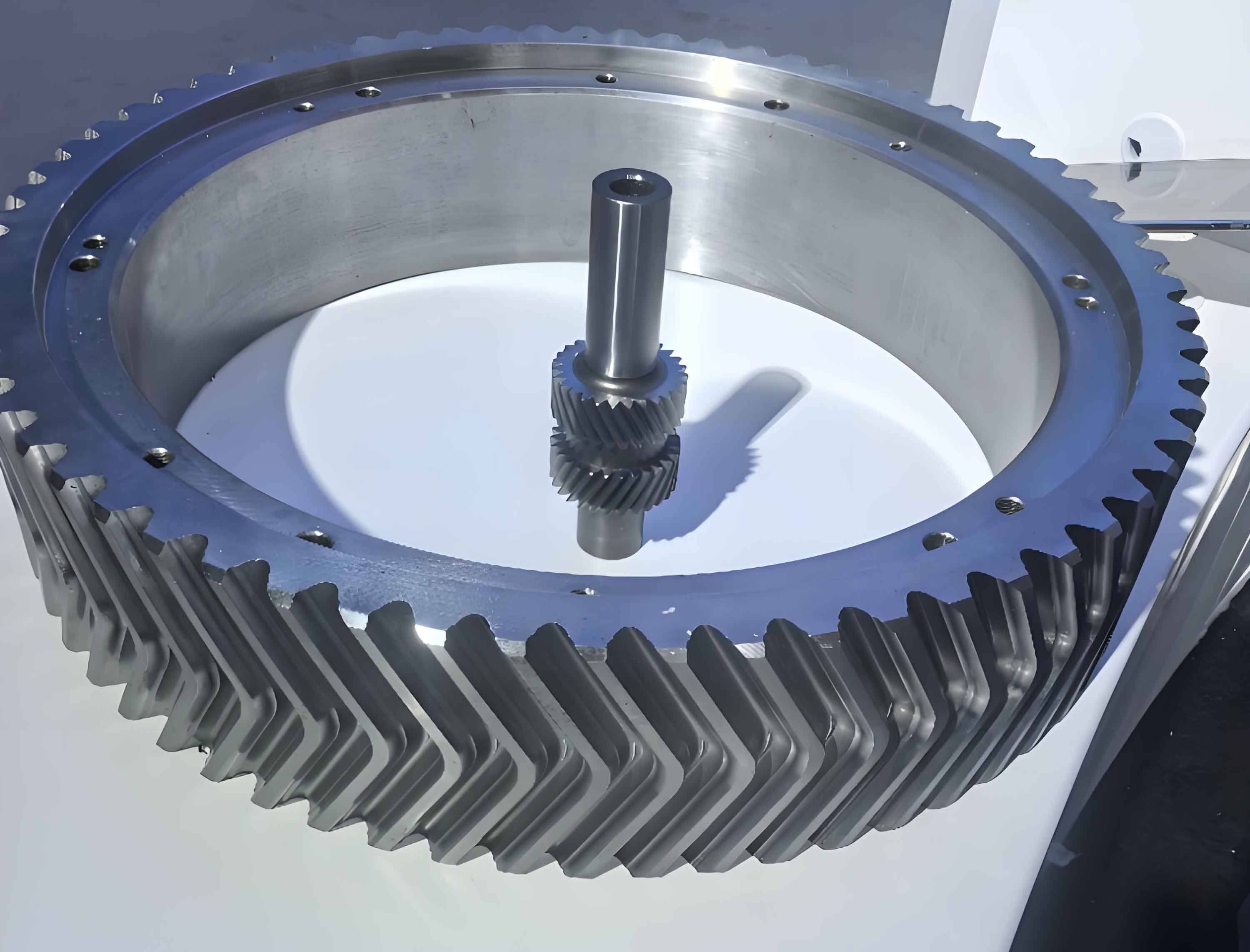

The herringbone gear, characterized by its symmetric V-shaped teeth, is widely adopted in reducers due to its ability to cancel axial forces and provide smooth operation. In a standard double-circular-arc herringbone gear, the teeth on the left and right sides are aligned such that convex profiles face convex profiles, and concave face concave. The staggered tooth concept involves axially shifting the teeth on one side relative to the other by a fraction of the axial pitch, typically half, resulting in a configuration where convex profiles on one side oppose concave profiles on the other. This misalignment alters the meshing dynamics, leading to an increase in the minimum number of simultaneous contact points during operation. For herringbone gears used in pumping unit reducers, this translates directly to higher load-bearing capacity. The principle is geometrically straightforward but yields profound effects on stress distribution and gear durability. We will explore this in detail, but first, let us formalize the concept.

Consider a herringbone gear with a total face width $B$, which includes the groove width for machining. The axial pitch $P_a$ is given by:

$$P_a = \frac{\pi m_n}{\sin \beta}$$

where $m_n$ is the normal module and $\beta$ is the helix angle. The face width can be expressed as $B = k P_a + \Delta$, where $k$ is an integer and $\Delta$ is the fractional part. For a standard herringbone gear, the axial distance between contact points on the same tooth is derived from the gear geometry. However, with staggered tooth arrangement, this distance changes. Let $P_a$ be the axial pitch, and let the shift be $\delta = 0.5 P_a$. This shift causes the convex and concave profiles to interlock differently, modifying the contact pattern. The key parameter affected is the minimum number of contact points $N_{min}$, which is crucial for load distribution. In our analysis of a typical pumping unit reducer, we found that staggered tooth herringbone gears increase $N_{min}$ by two points for the high-speed stage and three points for the low-speed stage, compared to standard herringbone gears. This increase is achieved without changing the overall dimensions, merely by adjusting the tooth alignment.

To understand the meshing characteristics, we analyze the contact point progression along the face width. For a standard double-circular-arc herringbone gear, the contact points alternate between convex and concave surfaces. The number of simultaneous contact points varies periodically, and the minimum value $N_{min}$ is determined by the overlap ratio and face width. With staggered tooth herringbone gears, the phase shift between left and right sides introduces additional contact points, effectively increasing $N_{min}$. This can be visualized using a meshing diagram where the contact patterns for left and right sides are offset. For instance, in a high-speed stage with parameters $m_n = 6$, $\beta = 25^\circ$, and $B = 200$ mm, the axial pitch $P_a \approx 44.4$ mm. The face width accommodates $k=4$ full pitches, and $\Delta \approx 22.2$ mm. For standard herringbone gears, $N_{min}$ is 4, while for staggered tooth herringbone gears, it becomes 6. Similarly, for a low-speed stage with $m_n = 8$, $\beta = 20^\circ$, and $B = 250$ mm, $P_a \approx 73.3$ mm, $k=3$, $\Delta \approx 40$ mm, and $N_{min}$ increases from 6 to 9. This enhancement is summarized in Table 1.

| Gear Stage | Standard Herringbone Gear $N_{min}$ | Staggered Tooth Herringbone Gear $N_{min}$ | Increase in Contact Points |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Speed | 4 | 6 | 2 |

| Low-Speed | 6 | 9 | 3 |

The increase in $N_{min}$ directly impacts the load capacity of the herringbone gear. In gear strength calculations, the contact stress and bending stress are inversely proportional to the number of contact points. For double-circular-arc gears, the contact is initially point-like, but under load, it spreads into an elliptical area. The stress distribution peaks at the center and tapers off towards the edges. When multiple contact points are present, the load is shared, reducing the stress at each point. Therefore, a higher $N_{min}$ leads to lower stresses and higher safety factors. The fundamental formulas for contact stress $\sigma_H$ and bending stress $\sigma_F$ in herringbone gears are adapted from standard gear theory, incorporating factors for the double-circular-arc profile and herringbone configuration.

The contact stress for a herringbone gear is given by:

$$\sigma_H = Z_E Z_H Z_\beta Z_\epsilon \sqrt{\frac{F_t K_A K_v K_{H\beta} K_{H\alpha}}{d_1 b N_{min}}}$$

where:

- $Z_E$ is the elasticity coefficient,

- $Z_H$ is the zone factor,

- $Z_\beta$ is the helix angle factor,

- $Z_\epsilon$ is the contact ratio factor,

- $F_t$ is the tangential force,

- $K_A$ is the application factor,

- $K_v$ is the dynamic factor,

- $K_{H\beta}$ is the face load factor for contact stress,

- $K_{H\alpha}$ is the transverse load factor for contact stress,

- $d_1$ is the pinion pitch diameter,

- $b$ is the face width, and

- $N_{min}$ is the minimum number of contact points.

For herringbone gears, $F_t$ is based on half the torque due to the symmetric design. The safety factor for contact strength $S_H$ is:

$$S_H = \frac{\sigma_{H\lim} Z_N Z_L Z_v Z_R Z_W}{\sigma_H}$$

where $\sigma_{H\lim}$ is the endurance limit, and $Z_N$, $Z_L$, $Z_v$, $Z_R$, $Z_W$ are life, lubricant, speed, roughness, and hardness factors, respectively.

The bending stress for a herringbone gear is:

$$\sigma_F = \frac{F_t K_A K_v K_{F\beta} K_{F\alpha} Y_\beta Y_\epsilon}{b m_n N_{min}} Y_F Y_S$$

where:

- $K_{F\beta}$ is the face load factor for bending stress,

- $K_{F\alpha}$ is the transverse load factor for bending stress,

- $Y_\beta$ is the helix angle factor for bending,

- $Y_\epsilon$ is the contact ratio factor for bending,

- $Y_F$ is the form factor, and

- $Y_S$ is the stress correction factor.

The safety factor for bending strength $S_F$ is:

$$S_F = \frac{\sigma_{F\lim} Y_N Y_\delta Y_R Y_X}{\sigma_F}$$

where $\sigma_{F\lim}$ is the bending endurance limit, and $Y_N$, $Y_\delta$, $Y_R$, $Y_X$ are life, size, roughness, and sensitivity factors.

In these equations, $N_{min}$ appears in the denominator for both stresses. Therefore, increasing $N_{min}$ reduces $\sigma_H$ and $\sigma_F$, thereby increasing $S_H$ and $S_F$. For staggered tooth herringbone gears, $N_{min}$ is replaced by $N_{min} + \Delta N$, where $\Delta N$ is the increase due to staggering. For example, if $N_{min}$ increases from 4 to 6, the contact stress is reduced by a factor of $\sqrt{6/4} \approx 1.225$, and the bending stress by a factor of $6/4 = 1.5$. This directly enhances the load capacity. We applied this to a pumping unit reducer model, with parameters typical for oil field operations. The reducer is a two-stage herringbone gear system, with both stages modified to staggered tooth configuration. Additionally, the face width of the low-speed stage was increased within the existing housing to maximize $N_{min}$.

Let us consider a detailed example. For a high-speed stage herringbone gear with: $m_n = 6$ mm, $\beta = 25^\circ$, $z_1 = 20$, $z_2 = 80$, $b = 200$ mm, input torque $T_1 = 5000$ Nm, material grade 42CrMo, and hardness 58 HRC. Using standard calculation methods, we compute the safety factors for both standard and staggered tooth configurations. The results are shown in Table 2.

| Parameter | Standard Herringbone Gear | Staggered Tooth Herringbone Gear | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum Contact Points $N_{min}$ | 4 | 6 | +2 |

| Contact Stress $\sigma_H$ (MPa) | 850 | 694 | -18.4% |

| Contact Safety Factor $S_H$ | 1.8 | 2.2 | +22.2% |

| Bending Stress $\sigma_F$ (MPa) | 280 | 187 | -33.2% |

| Bending Safety Factor $S_F$ | 2.5 | 3.75 | +50% |

For the low-speed stage herringbone gear with: $m_n = 8$ mm, $\beta = 20^\circ$, $z_1 = 30$, $z_2 = 120$, $b = 250$ mm (increased from 220 mm to utilize space), input torque $T_2 = 20000$ Nm, same material. The results are in Table 3.

| Parameter | Standard Herringbone Gear | Staggered Tooth Herringbone Gear | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum Contact Points $N_{min}$ | 6 | 9 | +3 |

| Contact Stress $\sigma_H$ (MPa) | 920 | 750 | -18.5% |

| Contact Safety Factor $S_H$ | 1.7 | 2.08 | +22.4% |

| Bending Stress $\sigma_F$ (MPa) | 320 | 213 | -33.4% |

| Bending Safety Factor $S_F$ | 2.2 | 3.3 | +50% |

The tables clearly demonstrate that staggered tooth herringbone gears yield significant reductions in stress and improvements in safety factors. Overall, the load capacity of the reducer is enhanced by approximately 30-35%, allowing it to handle over-torque conditions effectively. This makes the staggered tooth herringbone gear a viable upgrade for existing pumping units without necessitating major redesigns. In practice, we implemented this technology on several reducers in the field, and they have performed reliably under demanding conditions. The manufacturing process requires precise control of tooth alignment, but it is achievable with modern CNC gear cutting machines. The cost increment is minimal compared to the benefits of extended service life and reduced downtime.

Beyond pumping units, staggered tooth herringbone gears have potential applications in other industries such as metallurgy, mining, and heavy machinery, where high-torque reducers are essential. The principle of increasing $N_{min}$ through geometric modification can be adapted to various gear types, but it is particularly effective for double-circular-arc herringbone gears due to their point contact nature. Further research could explore optimal shift amounts (e.g., other fractions of $P_a$) and their effects on noise, vibration, and efficiency. However, our focus here is on load capacity, and the half-pitch shift has proven optimal for balancing contact pattern and manufacturing simplicity.

In conclusion, the staggered tooth technology for herringbone gears offers a straightforward yet powerful solution to enhance the load capacity of reducers in pumping units and beyond. By increasing the minimum number of simultaneous contact points, it reduces contact and bending stresses, leading to higher safety factors and longer gear life. The herringbone gear, with its inherent advantages, becomes even more robust with this modification. Our analysis and field applications confirm that staggered tooth herringbone gears can handle over-torque conditions up to 35% higher than standard designs, making them ideal for retrofitting existing equipment. As the petroleum industry continues to face challenges with aging infrastructure and harsh operating conditions, innovations like staggered tooth herringbone gears will play a crucial role in maintaining efficiency and reliability. We recommend widespread adoption of this technology, as it requires minimal investment and delivers substantial returns in performance and durability.