The pursuit of compact, high-performance robotic joints has consistently driven innovation in actuator and transmission technology. Among the various solutions, the strain wave gear, also commonly known as a harmonic drive, stands out due to its exceptional properties: high reduction ratios, compactness, lightweight design, and excellent positional accuracy with zero backlash. These attributes make the strain wave gear an indispensable component in precision robotics, collaborative robots, and aerospace applications where space and weight are at a premium.

However, advanced robotic applications, particularly those involving direct physical human-robot interaction or delicate manipulation tasks, require not just precise position control but also sophisticated force and impedance control. Implementing force control at the joint level necessitates an accurate, reliable, and low-latency measurement of the output torque. Traditional methods often involve mounting external rotary torque sensors on the joint output shaft. While effective, this approach invariably increases the axial length, inertia, and complexity of the joint module, counteracting the inherent advantages of the compact strain wave gear transmission.

This article presents a design methodology for a torque sensor that is intrinsically embedded within the strain wave gear assembly itself. The core concept leverages the inherent flexibility of a key component within the strain wave gear—the flexspline. By instrumenting the flexspline to measure its strain under load, we can directly infer the transmitted torque. This design philosophy aligns perfectly with the goal of joint miniaturization, as it adds sensing capability without significantly altering the external dimensions or mass of the joint module. The primary challenge lies in accurately extracting the torque-induced strain signal from the complex, dynamic strain field present in the rotating flexspline of a strain wave gear, which is also subjected to periodic deformation from the wave generator.

Fundamental Principles of the Strain Wave Gear and Torque Sensing

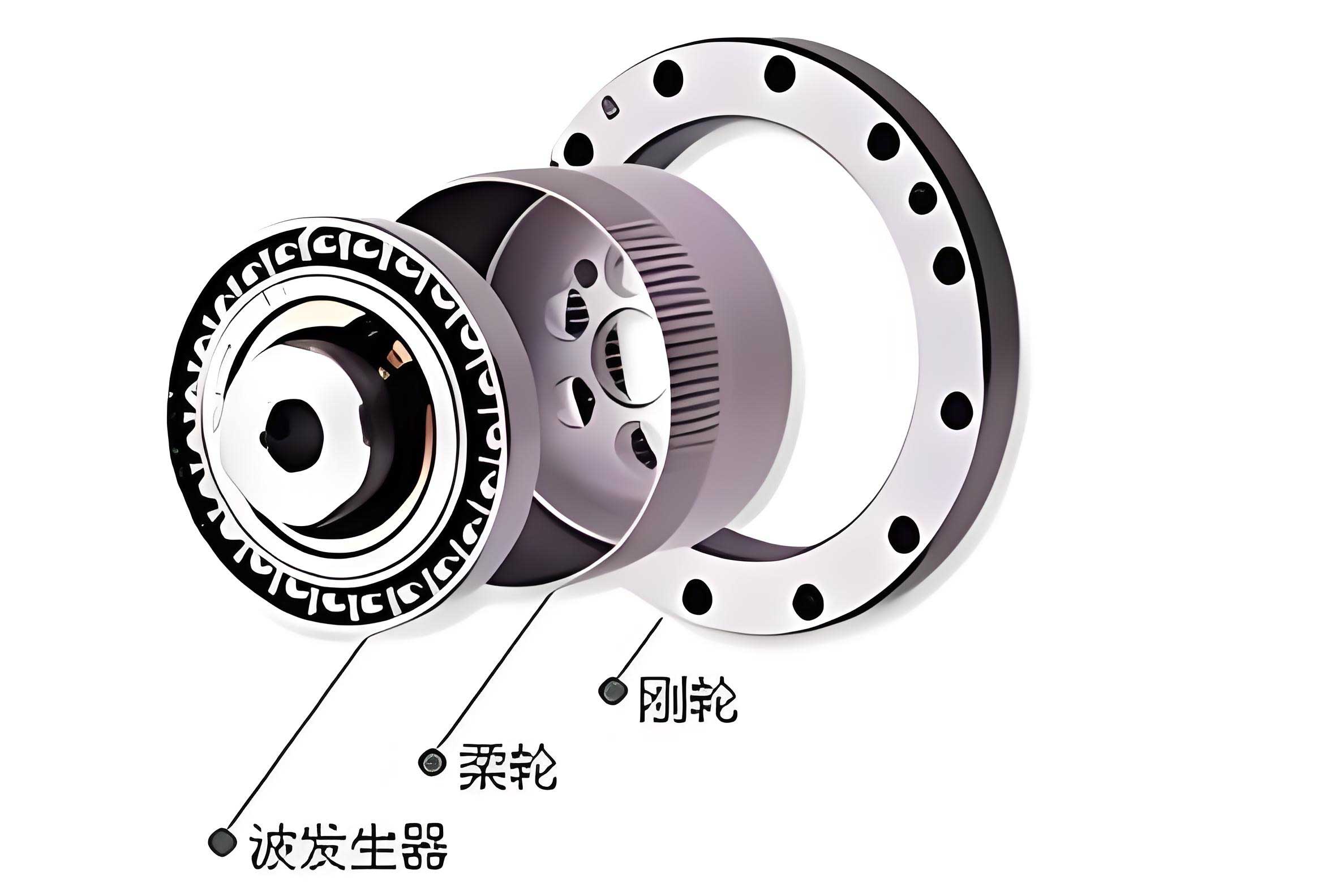

To understand the embedded sensor design, one must first grasp the basic kinematics and torque relationships within a strain wave gear. The system comprises three primary elements: the wave generator (input), the flexspline (output in a standard configuration), and the circular spline (stationary). The wave generator, typically an elliptical bearing assembly, deforms the flexible flexspline, causing its external teeth to engage with the internal teeth of the rigid circular spline at two diametrically opposite regions. The difference in the number of teeth between the flexspline and the circular spline creates a high reduction ratio as the wave generator rotates.

The torque relationship between the components is fundamental to our sensing approach. For a standard configuration with a fixed circular spline and rotating flexspline output, the torques are related by the gear reduction ratio, N.

$$T_{wg} = \frac{T_{cs}}{N+1} = \frac{T_{fs}}{N}$$

Where \(T_{wg}\) is the wave generator (input) torque, \(T_{cs}\) is the circular spline reaction torque, \(T_{fs}\) is the flexspline (output) torque, and \(N\) is the reduction ratio (e.g., 100:1). For a high reduction ratio \(N\), the flexspline torque \(T_{fs}\) is approximately \(N\) times larger than the input torque. More importantly for sensing, in a configuration where the flexspline is fixed and the circular spline is the output (a “cup-type” design), the relationship simplifies, and the torque through the flexspline body is directly and nearly equally related to the output torque at the circular spline. This configuration is often preferred for embedded sensing as it subjects the flexspline to a more constant stress field.

The flexspline is a thin-walled, cup-shaped elastic metal component. When transmitting torque, its diaphragm (the bottom of the cup) experiences shear stress, leading to a measurable angular strain. According to the theory of elasticity for a thin-walled cylindrical shell under torsion, the shear strain \(\varepsilon_a\) at the diaphragm can be approximated by:

$$\varepsilon_a = \frac{T_{fs} (r_1 + r_2)}{8\pi a G r_1^2 r_2}$$

where \(G\) is the shear modulus of the flexspline material, \(r_1\) is the radius of the diaphragm’s central hub, \(r_2\) is the outer radius of the diaphragm, and \(a\) is the thickness of the diaphragm. This equation forms the theoretical foundation: the strain on the flexspline diaphragm is directly proportional to the torque it transmits (\(T_{fs}\)). Therefore, by accurately measuring \(\varepsilon_a\), we can determine \(T_{fs}\) and, consequently, the output torque of the joint module incorporating the strain wave gear.

Sensor Design and Strain Gauge Configuration

The practical implementation of this principle involves the use of metallic foil strain gauges. These gauges exhibit a change in electrical resistance proportional to the applied strain. The core design task is to configure these gauges to maximize sensitivity to the torsional (shear) strain while rejecting spurious signals from other sources.

The most significant source of noise is the periodic, wave generator-induced deformation of the flexspline. As the elliptical wave generator rotates, it forces the flexspline into an elliptical shape, creating a large, spatially rotating bending strain that is unrelated to the transmitted torque. If a single strain gauge were used, its signal would be dominated by this unwanted “ripple” at twice the wave generator rotation frequency.

To cancel this effect, a symmetrical configuration of multiple strain gauges is employed. The most common and effective approach uses four pairs of strain gauges bonded to the flexspline diaphragm. Each pair consists of two gauges oriented at 90 degrees to each other (a tee rosette). The four pairs are distributed at 90-degree intervals around the diaphragm’s circumference. This configuration is designed to be sensitive to the pure shear strain field caused by torque, which has a consistent sign around the circumference, while the bending strain from the wave generator alternates in sign at opposing points.

The gauges are connected to form a full Wheatstone bridge circuit. The arrangement ensures that gauges experiencing tensile strain under torque are placed in adjacent bridge arms, while those in compression are placed opposite. The wave generator-induced bending strains, being antisymmetric, produce equal and opposite changes in resistance in strategically paired arms of the bridge, resulting in their cancellation at the output. The output voltage \(U_{out}\) of an ideal bridge with perfect gauge placement becomes a clean function of the torsional strain:

$$U_{out} = 2 K \varepsilon_a E_{sup}$$

where \(K\) is the gauge factor of the strain gauges and \(E_{sup}\) is the bridge excitation voltage.

Combining this with the strain-torque relation, we derive the intrinsic sensitivity \(K_R\) of the embedded sensor (before signal amplification):

$$K_R = \frac{U_{out}}{T_{fs}} = \frac{K E_{sup} (r_1 + r_2)}{4\pi a G r_1^2 r_2}$$

The following table summarizes the key design parameters and their influence on the strain wave gear embedded torque sensor’s performance.

| Parameter | Symbol | Role in Sensor Design | Design Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shear Modulus | \(G\) | Material property linking stress and strain. | High \(G\) (e.g., alloy steel) reduces strain for a given torque, requiring more sensitive electronics. |

| Diaphragm Thickness | \(a\) | Directly inversely proportional to strain and sensitivity \(K_R\). | A thinner diaphragm increases sensitivity but reduces mechanical strength and maximum torque capacity. |

| Hub & Diaphragm Radii | \(r_1, r_2\) | Geometric factors in the strain equation. | Optimized based on the overall strain wave gear size and desired strain distribution. |

| Gauge Factor | \(K\) | Converts mechanical strain to electrical resistance change. | A higher \(K\) (e.g., 2.0) yields a larger output signal. |

| Bridge Excitation | \(E_{sup}\) | Scales the output voltage linearly. | Limited by gauge power dissipation and signal conditioning circuit design. |

| Reduction Ratio | \(N\) | Relates flexspline torque \(T_{fs}\) to joint output torque. | A fundamental property of the chosen strain wave gear. |

Precision Manufacturing and Signal Processing

While the four-pair symmetrical bridge theory promises perfect ripple cancellation, practical implementation is hindered by manufacturing tolerances. Imperfect gauge placement—deviations from exact 90-degree alignment within a pair or from perfect 90-degree circumferential spacing—leaves a residual ripple signal in the output. This residual is often called “torque ripple” and occurs at a frequency related to the wave generator rotation and the gear meshing frequency (typically twice the wave generator frequency).

Laser-Assisted Precision Alignment

To minimize this geometric error source, a laser marking technique is employed prior to gauge bonding. Finite Element Analysis (FEA) of the flexspline diaphragm under load identifies the region of maximum and most uniform shear strain. A precise laser marker is then used to etch alignment fiducials directly onto the diaphragm surface at these optimal locations. These fiducials provide a visible, high-accuracy guide for the manual or automated placement of each strain gauge, ensuring near-perfect angular and positional alignment. This step is critical for achieving high signal fidelity and is a key advancement over traditional freehand or simple jig-based mounting methods for sensors integrated into a strain wave gear.

Kalman Filtering for Dynamic Ripple Rejection

Even with laser-guided placement, minor asymmetries and dynamic effects mean the output signal contains some residual high-frequency torque ripple. A standard low-pass filter is insufficient because the ripple frequency varies directly with the joint rotation speed. A more sophisticated approach uses a Kalman filter, an optimal estimator that is particularly effective for systems with well-defined dynamics and measurement noise.

The system dynamics can be modeled with two primary states: the actual transmitted torque (which changes relatively slowly based on load conditions) and the residual ripple (modeled as a sinusoidal disturbance). The Kalman filter recursively predicts the system state based on a model and then corrects the prediction using the noisy strain gauge measurements. It optimally balances the trust between the model’s prediction and the new measurement, effectively isolating and suppressing the time-varying ripple component while preserving the true torque signal. The filter’s performance is superior to fixed filters because it adapts its estimation based on the statistical properties of the noise, leading to a significant smoothing of the output signal, especially during constant-torque operations or at speed transitions, without introducing phase lag that would be detrimental for force control.

Experimental Validation and Calibration

A prototype joint module was constructed using a standard commercial “cup-type” strain wave gear (where the flexspline is fixed, and the circular spline rotates as the output). Four pairs of strain gauges were bonded to the flexspline diaphragm using the laser fiducial method. The gauge bridge output was amplified and digitized. The module was integrated into a test rig consisting of a servo motor input, the instrumented strain wave gear, and a output shaft connected to a high-precision, calibrated reference rotary torque sensor and a magnetic powder brake to apply variable loads.

Testing was conducted in both static and dynamic regimes. For static calibration, the motor applied a series of stepped torque commands, and the steady-state output from both the embedded sensor and the reference sensor was recorded. A dynamic test involved commanding a constant motor torque while the load brake applied a sinusoidal torque profile to the output, simulating a varying external force.

The raw output from the embedded sensor, after amplification, showed a strong linear correlation with the reference torque but with a visible superimposed ripple, particularly in dynamic tests. After applying the Kalman filter, the ripple was substantially attenuated. The static calibration data was used to determine the sensor’s operational sensitivity and to establish the relationship between the measured flexspline torque (\(T_{fs,measured}\)) and the actual joint output torque (\(T_{output}\)). This relationship accounts for factors not in the ideal model, such as minor power losses and load-dependent deflections in the strain wave gear assembly.

The analysis yielded linear calibration equations. For the static case:

$$T_{output, static} = C_{s1} \cdot T_{fs,measured} + C_{s0}$$

For the dynamic case:

$$T_{output, dynamic} = C_{d1} \cdot T_{fs,measured} + C_{d0}$$

The coefficients \(C_{s1}, C_{s0}, C_{d1}, C_{d0}\) are determined empirically. The slight difference between static and dynamic coefficients reflects the influence of dynamic factors like viscous damping and slight hysteresis within the strain wave gear under motion.

The following table presents typical performance results from the prototype validation, demonstrating the effectiveness of the strain wave gear-embedded torque sensor design.

| Test Condition | Calibration Coefficients | Max Absolute Error | Root Mean Square (RMS) Error | RMS Error (% of Full Scale) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Static (Stepped Load) | \(C_{s1} = 1.284, C_{s0} = -0.0812\) Nm | 0.39 Nm | 0.21 Nm | 1.04% |

| Dynamic (Sinusoidal Load) | \(C_{d1} = 1.572, C_{d0} = -0.0928\) Nm | 0.64 Nm | 0.265 Nm | 1.27% |

Application in Robotic Joints and Conclusion

The integration of this embedded torque sensing technology into a robotic joint module based on a strain wave gear provides a profound advantage. It enables direct, joint-level force sensing without the drawbacks of external sensors. The compact form factor is preserved, making it ideal for collaborative robots (cobots) with strict size limitations, humanoid robots with many degrees of freedom, and exoskeletons where low inertia is critical.

The availability of a high-fidelity torque signal at the joint facilitates advanced control strategies. These include:

- Direct Force Control: The joint can be controlled to output a specific torque, essential for tasks like assembly, polishing, or physical human-robot interaction.

- Impedance/Admittance Control: The joint can be programmed to behave like a spring-damper system with variable parameters, allowing for compliant and safe interaction with the environment.

- Collision Detection and Safety: Rapid detection of unexpected torque spikes can trigger an emergency stop or a gentle retreat maneuver, enhancing operational safety.

- Friction and Load Compensation: The measured torque can be used in feedforward control loops to compensate for nonlinearities like friction within the strain wave gear and motor, improving tracking accuracy.

In conclusion, the design of a torque sensor embedded within the flexspline of a strain wave gear represents a highly effective synergy between mechanical transmission and sensing. By leveraging the component’s inherent flexibility and employing precision manufacturing (laser alignment) and advanced signal processing (Kalman filtering), we achieve accurate torque measurement with minimal impact on the joint module’s size and weight. This approach successfully addresses the core challenge of separating the desired torque signal from the significant kinematic deformation noise inherent in the strain wave gear’s operation. The experimental results confirm that the embedded sensor can estimate joint output torque with an error of approximately 1-1.3% of full scale, meeting the requirements for sophisticated robotic force control. This technology paves the way for a new generation of highly integrated, sensor-rich, and performance-optimized robotic actuators.