In my extensive experience analyzing power transmission systems, the design and implementation of herringbone gears present a fascinating set of challenges that are often overlooked. A herringbone gear is essentially a pair of identical helical gears with opposite hand of helix machined or assembled on a common shaft. This configuration offers the prized benefits of helical gearing—smooth, quiet operation and high load capacity—while theoretically canceling out the net axial thrust generated by the helical teeth. This theoretical perfection, however, is shattered by the realities of manufacturing. The critical flaw lies not in the concept but in the practical impossibility of achieving perfect alignment of the two gear halves during production. This misalignment, which I will refer to as the phase error or tooth coincidence error, has profound implications for the entire shaft-bearing system. It dictates that for a pair of herringbone gears to mesh correctly under load, axial movement, or “float,” of at least one shaft is not just beneficial—it is an absolute mechanical imperative. Ignoring this requirement during design or application leads directly to improper loading, excessive wear, and premature failure.

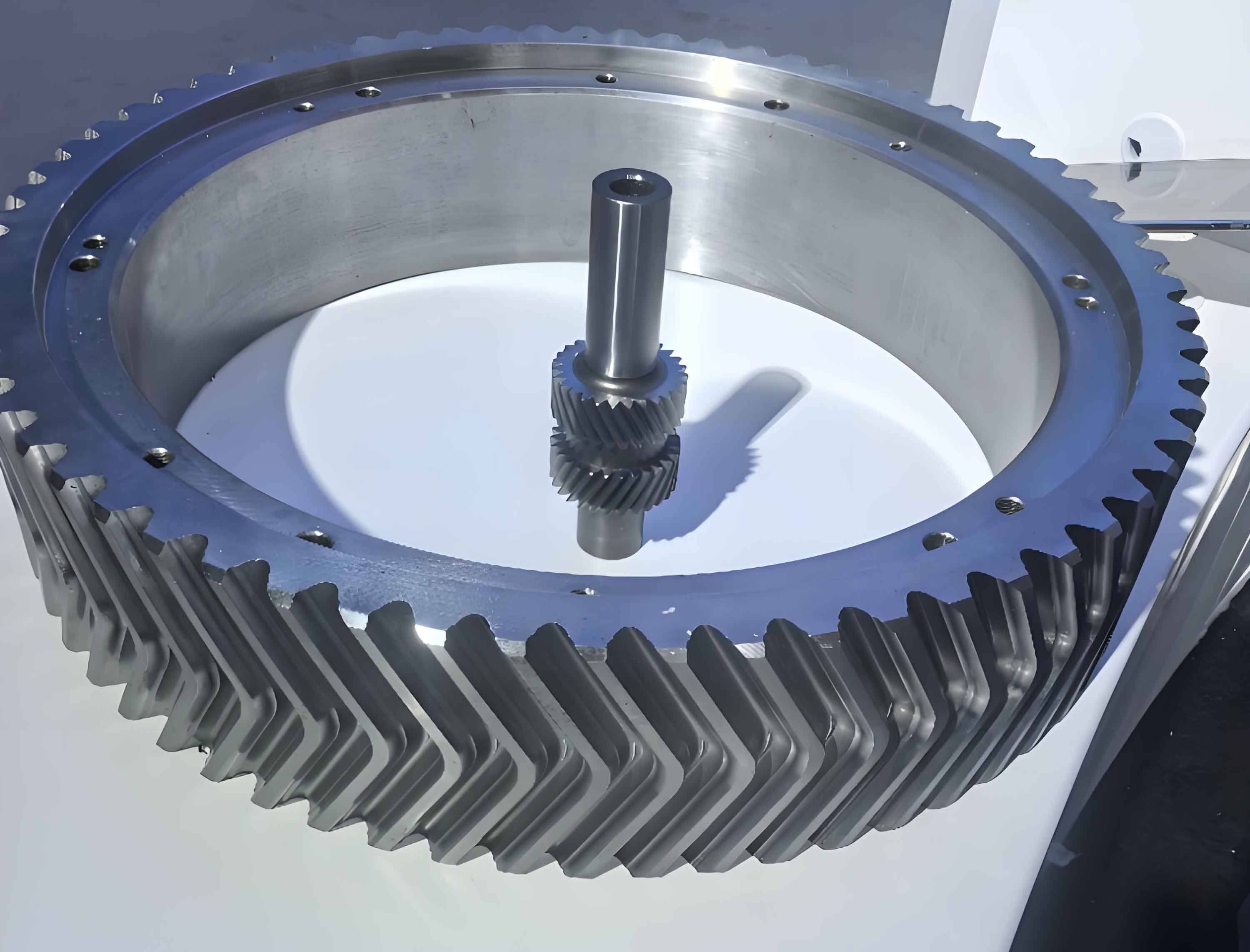

The visual representation above clearly shows the distinct left and right-hand helical threads forming the characteristic “V” shape of herringbone gears. The precise alignment of the apex of this V across the gear face is what manufacturing strives for, but inevitably misses.

The necessity for phase accuracy becomes clear when we model the meshing condition. Let us consider a driving and a driven herringbone gear pair. For perfect, simultaneous contact on both flanks, the corresponding teeth on the left and right helices of one gear must be perfectly aligned with the tooth spaces of the mating gear. Now, assume the driven gear is our reference, manufactured with perfect internal phase (a theoretical ideal). The driving herringbone gear, however, has a manufacturing phase error. This means the left helix is rotationally offset relative to the right helix by a small angle. When this gear is mounted on its shaft, its teeth will not simultaneously engage correctly with the driven gear. To achieve dual-flank contact, one of the helical halves must shift axially until its teeth align properly with the mating gear’s spaces.

We can quantify this relationship. Let the phase error be denoted as $\Delta$, measured as a linear displacement along the pitch circle. Let the required axial shift of the single helical half to correct this error be $\delta_s$, and the helix angle be $\beta$. The axial shift is related to the circumferential error by the helix lead. The relationship is given by:

$$\delta_s = \frac{\Delta}{\tan \beta}$$

This equation reveals a critical insight: for a given phase error $\Delta$, a smaller helix angle $\beta$ results in a larger required axial shift $\delta_s$. This is because a lower helix angle means a longer lead, so a smaller rotational error translates to a larger axial movement.

In reality, a system cannot practically allow one helical half to move independently. Therefore, the compensation occurs through the axial float of the entire gear shaft. In a balanced state, both helices move axially by half the distance needed to correct the total misalignment, sharing the adjustment equally. Consequently, if the driving gear has a phase error $\Delta_1$ and the driven gear has a phase error $\Delta_2$, the total system phase error is $\Delta_{total} = \Delta_1 + \Delta_2$. The resulting axial float $\delta$ required for the shaft to find its equilibrium meshing position is approximately:

$$\delta \approx \frac{\Delta_{total}}{2 \tan \beta}$$

This formula is foundational for understanding the behavior of herringbone gears. It shows that the axial float is directly proportional to the sum of the manufacturing errors and inversely proportional to the tangent of the helix angle.

The following table summarizes the impact of key parameters on the required axial float:

| Parameter | Trend | Effect on Required Axial Float ($\delta$) |

|---|---|---|

| Phase Error ($\Delta_{total}$) | Increases | Increases linearly |

| Helix Angle ($\beta$) | Increases | Decreases significantly |

| Manufacturing Precision | Improves (lower $\Delta$) | Decreases |

The implications for bearing selection are decisive and non-negotiable. The bearing system must accommodate this inherent axial float. Choosing a bearing arrangement that rigidly locks the shaft axially at both ends is a fundamental design error for herringbone gears. Let’s examine the consequences of such a restriction and the correct philosophy for bearing configuration.

If a herringbone gear shaft is axially fixed at both ends by its bearings, only two scenarios are possible, both detrimental. In the first scenario, the bearings are positioned and locked before the gears are fully engaged. This forces the herringbone pair into a state where one helix is in tight contact while the other has backlash. The system effectively operates as a single helical gear, with all the transmitted load passing through one helix. This doubles the specific load on the contacting teeth, leading to accelerated pitting, bending fatigue, and catastrophic failure. The second scenario involves adjusting the bearings after perfectly meshing the gears. However, since the phase error is a fixed geometric property, the shaft is now preloaded against the bearing races. Any dynamic effects, thermal expansion, or slight wear will create fluctuating internal axial forces, adding parasitic loads to the bearings and reducing their lifespan significantly.

Therefore, the only correct approach is to design the shaft system to allow for controlled axial float. The standard and most reliable practice is the fixed-float bearing arrangement. One shaft (typically the slower-speed, higher-torque driven shaft) is axially located using bearings that prevent movement. The other shaft (typically the pinion or driving shaft) is supported with a “float” end. This is often achieved using a cylindrical roller bearing (NU or N type) or a deep groove ball bearing with sufficient axial clearance on one side, which allows free axial movement. This configuration permits the floating shaft to find its natural axial equilibrium position where both helices of the herringbone gears share the load equally.

The choice of which shaft floats is strategic. Floating the pinion is often preferred because it is usually smaller, carries less inertia, and its float has less impact on other connected components (like couplings or motors). However, the entire system layout must be reviewed to ensure that the required axial movement does not interfere with seals, couplings, or other adjacent machinery elements.

Beyond bearing type, the management of phase error is a critical design input. While it is impossible to eliminate $\Delta_{total}$, it must be strictly controlled through manufacturing tolerances. The trade-off is cost: tighter phase tolerances require more precise and expensive machining processes. The designer must specify an economically viable phase error limit that, when combined with the chosen helix angle, results in an axial float $\delta$ that is manageable within the mechanical constraints of the system (e.g., allowable coupling misalignment, seal tolerance). A common industrial guideline is to keep the calculated float within a few tenths of a millimeter.

| Design Aspect | Consideration & Guideline |

|---|---|

| Bearing Arrangement | Mandatory fixed-float configuration. Never use double-axial fixation. |

| Floating Bearing Type | Cylindrical roller bearings (non-locating) or deep groove ball bearings with axial clearance. |

| Shaft to Float | Typically the pinion/driving shaft. Evaluate system interfaces. |

| Helix Angle ($\beta$) | Select sufficiently large (e.g., 20°-30°) to minimize axial float from a given phase error. Avoid very low angles. |

| Phase Error Tolerance ($\Delta$) | Specify as a tight manufacturing requirement. Balance cost with allowable float $\delta$. |

| System Integration | Ensure adequate space for axial movement. Use flexible couplings. Protect float path from obstruction. |

In high-performance or critical applications, more sophisticated solutions can be employed. For instance, using a double-helical gear with a centrally located groove (true herringbone) machined from a single blank reduces phase error compared to assembling two separate helical gears. Furthermore, bearing technologies like hydrodynamic journal bearings with thrust collars can naturally accommodate slight axial movements while maintaining load capacity. For ultra-precision systems, the use of preloaded tapered roller bearings on both shafts is sometimes seen, but this requires the herringbone gears to be manufactured with exceptionally low phase error, effectively making the float negligible and the preload dominant; this is a high-cost solution.

From a systems engineering perspective, the behavior of herringbone gears has cascading effects. The axial float is not a static offset; it can be dynamic, changing slightly with load, temperature, and wear. This necessitates robust sealing solutions that can handle small axial oscillations without leaking. Lubrication systems must be designed to ensure both helices are adequately lubricated throughout the range of axial travel. Vibration analysis must account for the fact that the gear mesh stiffness may vary slightly with the axial position of the floating shaft.

A crucial safety and maintenance protocol stems from this design: the floating shaft must never be mechanically impeded. During installation or service, locking devices used for transport must be removed. Couplings must be aligned with care to avoid introducing external axial forces that could “pin” the shaft and defeat the float. Routine maintenance should include checks for any unintended restriction of axial movement.

To consolidate the design process for herringbone gear systems, I propose the following step-by-step guidelines:

- Define Operating Conditions: Determine power, speed, torque, and life requirement.

- Select Gear Geometry: Choose module, face width, and a helix angle $\beta$ of at least 20° to limit sensitivity to phase error.

- Specify Manufacturing Tolerance: Set a maximum allowable phase error $\Delta_{total}$ for the gear pair based on capability and cost.

- Calculate Required Float: Use $\delta \approx \frac{\Delta_{total}}{2 \tan \beta}$ to estimate the necessary axial movement.

- Design Bearing System: Adopt a fixed-float arrangement. Select bearing types (e.g., tapered roller for fixed end, cylindrical roller for float end) suitable for radial loads and the calculated float range.

- Integrate System Components: Design shaft seals, couplings, and housing to accommodate the axial float $\delta$ without interference.

- Implement Safety Measures: Ensure the float path is clear and consider external locking devices for transport only, with clear warnings for their removal.

The analysis of herringbone gears reveals a beautiful interplay between theory and practice. The theoretical cancellation of axial thrust is a powerful motivation for their use in heavy-duty applications like marine propulsion, rolling mills, and large compressors. However, the practical requirement for axial float due to manufacturing imperfections is an inescapable reality. Successfully implementing herringbone gears hinges on acknowledging this imperative at the earliest design stage and propagating it through every subsequent decision—from gear machining tolerances and bearing selection to final system integration. The correct application of herringbone gears results in a robust, efficient, and long-lasting transmission system. Conversely, neglecting the axial float requirement is a guarantee of operational problems and reduced mechanical integrity.