In the manufacturing of hypoid gear pairs, achieving the desired contact pattern on the tooth flanks has traditionally relied on empirical adjustments of curvature corrections along the face width (lengthwise) and profile (heightwise) directions. However, the results from this approach are often inconsistent and unsatisfactory. This study re-examines the problem from the fundamental perspective of the contact pattern formation process. By analyzing the geometry along the potential contact lines and the path of contact, a more precise methodology for determining the appropriate magnitude of curvature modification is proposed. Key concepts and formulas for calculating these curvature modifications are established and analyzed. Experimental verification was conducted, yielding highly satisfactory and predictable results. The core conclusion is that by strategically selecting the position of the designated contact reference point and the associated curvature modification values in the gear cutting calculations, one can effectively control the location, shape, and size of the contact pattern. Furthermore, this approach provides a means to control gear noise from the perspective of tooth surface topology.

A new insight arising from extensive calculations is that altering the cutter point diameter for the pinion directly influences the length of the potential contact line, challenging traditional views on cutter diameter effects. This paper will detail the theoretical foundation, computational framework, and experimental validation of this methodology for controlling the contact pattern in hypoid gear pairs.

1. The Formation Process of the Contact Pattern

Consider a hypoid gear pair mounted on a testing machine. After applying a marking compound (e.g., Prussian blue) to the teeth, the gear is rotated under light load to transfer the compound and reveal areas of contact. If the gear pair were in perfect theoretical line contact, the entire potential contact line would be marked. However, due to deliberate modifications and inevitable errors, only an elliptical patch, known as the contact pattern or bearing, appears. The formation process can be visualized conceptually: if the gear pair could be engaged, disengaged, rotated by a small angle, and re-engaged repeatedly, a series of discontinuous contact ellipses would be observed along the tooth surface. The centroid of each small ellipse represents an instantaneous point of contact. The line connecting these centroids forms the path of contact on the gear tooth surface. Under typical conditions, this path is nearly a straight line.

The key geometric elements defining the contact pattern are:

- Virtual Contact Line ($\mathbf{\xi}$): The theoretical line of contact between the perfectly conjugate gear surfaces at the designated reference point. Its unit tangent vector is denoted as $\mathbf{\xi}$. The length of this line segment, denoted as $L_{\xi}$, is finite in practice due to modifications.

- Path of Contact ($\mathbf{\zeta}$): The actual trajectory of contact points on the gear tooth surface under load. Its unit tangent vector is denoted as $\mathbf{\zeta}$, and its length is $L_{\zeta}$.

- Tooth Profile Direction ($\mathbf{h}$): Approximately the direction of the tooth height.

- Face Width Direction ($\mathbf{f}$): Approximately the direction along the tooth length.

The location, shape, and size of the contact pattern are predominantly governed by five parameters: the angles $\alpha$ (between $\mathbf{\xi}$ and $\mathbf{f}$) and $\beta$ (between $\mathbf{\zeta}$ and $\mathbf{f}$), the lengths $L_{\xi}$ and $L_{\zeta}$, and the position of the path of contact on the tooth surface. The angle $\alpha$ is largely determined by the basic gear design parameters and is not typically a free variable for adjustment. Therefore, effective control of the contact pattern hinges on the strategic calculation and implementation of curvature modifications that influence $L_{\xi}$, $L_{\zeta}$, $\beta$, and the path position.

2. Fundamental Theory and Calculation of Tooth Surface Curvature Modification

2.1 Normal Curvature Modification along the Virtual Contact Line Direction ($\mathbf{\xi}$)

The length of the virtual contact line, $L_{\xi}$, is primarily determined by the normal curvature modification applied to the pinion surface along the $\mathbf{\xi}$ direction relative to the theoretical conjugate surface. Consider the theoretical line contact between the gear (surface $\Sigma_2$) and the pinion (surface $\Sigma_1$). To achieve a localized contact pattern, the pinion surface is modified to a new surface $\Sigma_1’$, which is point contact with $\Sigma_2$ at the reference point.

The normal curvature modification $\Delta K_{x\xi}$ for the pinion along $\mathbf{\xi}$ can be derived from simple geometric considerations. If the theoretical surfaces contact along a line, their induced normal curvature in the $\mathbf{\xi}$ direction is zero. Introducing a modification $\Delta K_{x\xi}$ effectively changes the pinion’s cross-sectional curvature in the plane containing the surface normal and the $\mathbf{\xi}$ direction to a circular arc with radius $R = 1 / \Delta K_{x\xi}$. The relationship governing the contact ellipse size in this direction is given by:

$$ \Delta K_{x\xi} = \frac{2a}{L_{\xi}^2} $$

where $a$ is the semi-major axis of the contact ellipse. For a desired contact pattern length $L_{\xi}$ and under typical testing conditions, an empirical value for $a$ can be chosen. For instance, if $a$ is set to a specific value (e.g., derived from testing standards), the formula simplifies to a direct calculation for $\Delta K_{x\xi}$ to achieve a target $L_{\xi}$.

2.2 Determination of the Path of Contact Direction ($\mathbf{\zeta}$) on the Pinion

The direction of the path of contact, $\mathbf{\zeta}$, on the pinion is not arbitrary but is defined by the kinematic and geometric conditions of point contact. For two surfaces in point contact with a specified velocity ratio and its derivative (acceleration) at the contact point, there exists a unique direction on the pinion surface along which the two surfaces can maintain continuous contact in the differential neighborhood. This direction is the path of contact $\mathbf{\zeta}$.

Geometrically, $\mathbf{\zeta}$ on the pinion and $\mathbf{\zeta}_g$ on the gear are conjugate directions. Their relationship can be found using the condition of contact continuity and the fundamental law of gearing. The relative motion between the pinion and gear at the point of contact can be reduced to the rolling/sliding and twisting of a plane over a cylindrical surface when in line contact. In the point contact scenario ($\Sigma_1’$ and $\Sigma_2$), only the direction $\mathbf{\zeta}$ that is perpendicular to the change in the surface normal relative to this reduced motion allows for maintained contact. The angle $\theta$ between $\mathbf{\zeta}_g$ and $\mathbf{\zeta}$ on their respective surfaces, measured around the common surface normal $\mathbf{n}$, can be calculated from known kinematic relations:

$$ \tan \theta = \frac{- \Omega_{\zeta}}{v_{\sigma}} $$

Where specific terms relate to the relative angular velocity and sliding velocity components. In practice, the direction $\mathbf{\zeta}_g$ on the gear is often chosen first based on desired contact pattern orientation (e.g., slightly diagonal), and the corresponding $\mathbf{\zeta}$ on the pinion is computed.

2.3 Curvature Modification along the Path of Contact Direction ($\mathbf{\zeta}$)

The curvature modification along $\mathbf{\zeta}$ is crucial for controlling the length of the contact pattern $L_{\zeta}$ and is intimately linked to the transmission error curve.

Transmission Error Curve: This curve plots the angular deviation of the driven gear from its theoretical position as a function of the driver gear’s rotation when the driver rotates at constant speed. A perfectly conjugate pair would have zero transmission error (a straight line). To reduce noise and impact, a mild, smoothly varying transmission error curve is desirable. A convex-shaped curve for a single tooth pair is often targeted, as it provides better resistance to machining errors and lighter meshing impacts compared to a concave curve.

The second derivative of the transmission error curve is related to the acceleration or the change in instantaneous gear ratio. For a convex curve, this value is negative on the drive side and positive on the coast side.

Calculation of Modification $\Delta K_{x\zeta}$: The targeted transmission error modification $\Delta TE$ (the deviation from linear motion) directly influences the required curvature modification. The maximum induced normal curvature along the relevant direction is derived from the kinematics of the meshing process. The relationship can be expressed as:

$$ \Delta K_{I\zeta} = – \frac{\Delta TE”}{(\mathbf{v}_{\sigma} \cdot \mathbf{\zeta})^2} $$

where $\Delta TE”$ is the second derivative of the transmission error function, and $\mathbf{v}_{\sigma}$ is the relative sliding velocity vector. This $\Delta K_{I\zeta}$ represents the induced normal curvature modification needed between the theoretical line contact surfaces to produce the desired motion. This must then be allocated as a normal curvature modification $\Delta K_{x\zeta}$ on the pinion surface along the $\mathbf{\zeta}$ direction.

2.4 The Relative Conjugate Curvature Circle and Comprehensive Modification

The various curvature modifications ($\Delta K_{x\xi}$, $\Delta K_{x\zeta}$) and the associated geodesic torsion modifications ($\Delta G_{x\xi\zeta}$) are not independent. They are linked through the geometry of the surface and the condition of point contact. A powerful tool for visualizing and calculating these relationships is the Relative Conjugate Curvature Circle (or simply, the relative curvature circle).

This circle represents all possible induced normal curvatures between the modified pinion and the gear surfaces in every direction tangent to the surface at the reference point. On this circle:

- The horizontal axis represents the induced normal curvature ($\Delta K_I$).

- The vertical axis represents the induced geodesic torsion ($\Delta G_I$).

- Every point on the circle corresponds to a specific tangent direction on the pinion surface. The angle between directions on the tooth surface corresponds to twice the angle between their representative points on the circle.

Key directions like $\mathbf{f}$, $\mathbf{h}$, $\mathbf{\xi}$, and $\mathbf{\zeta}$ can be plotted on this circle. Their positions are determined by their calculated curvature modification values. The relative conjugate curvature circle must lie entirely on the positive side of the normal curvature axis for a feasible, localized contact pattern. The geometric relationships on this circle allow us to compute the modification in one direction if modifications in other directions are known. For instance, knowing $\Delta K_{x\xi}$ and $\Delta K_{x\zeta}$, the modification in the tooth profile direction $\Delta K_{xh}$ can be derived, which is often related to the “crowning” or “barreling” of the tooth.

The comprehensive set of modification calculations ensures that the final manufactured pinion surface will produce the intended contact pattern characteristics when meshed with its gear mate.

3. Experiment and Results

3.1 Machine Tool and Test Hypoid Gear Parameters

Experiments were conducted on standard hypoid gear generators. The test hypoid gear pair was selected based on a common automotive application (similar to parameters for a truck differential). The primary parameters are summarized in Table 1.

| Parameter | Pinion | Gear |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Teeth | 11 | 41 |

| Gear Ratio | 3.727 | |

| Shaft Offset | 45 mm | |

| Mean Spiral Angle | 47° 30′ (LH) | 32° 30′ (RH) |

| Mean Pressure Angle | 21° 15′ | |

| Face Width | – | 58 mm |

| Working Depth at Midpoint | 10.668 mm | |

3.2 Cutting Data and Curvature Modification Settings

Several test cuts were performed with different sets of calculated curvature modification parameters. The pinion concave side was finished in each case. Key machine settings derived from the calculation for three distinct test cases (A, B, C) are shown in Table 2. These include the calculated curvature modifications ($\Delta K_{x\xi}$, $\Delta K_{x\zeta}$), the resulting machine setup corrections (e.g., change in machine center to back, swivel angle, etc.), and the consequential cutter point diameter.

| Calculation Item / Test Case | Case A | Case B | Case C |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pinion Normal Curvature Mod. $\Delta K_{x\xi}$ (1/mm) | 1.45e-4 | 1.45e-4 | 0.95e-4 |

| Pinion Normal Curvature Mod. $\Delta K_{x\zeta}$ (1/mm) | 2.10e-4 | 1.65e-4 | 1.65e-4 |

| Path of Contact Angle $\beta$ (deg) | ~90° | ~60° | ~45° |

| Machine Center to Back Change (mm) | +0.12 | -0.05 | -0.10 |

| Swivel Angle Change (min) | +10 | -5 | -15 |

| Resultant Cutter Point Diameter (mm) | 173.850 | 171.624 | 170.968 |

3.3 Test Results and Analysis

The contact patterns obtained from the three test cases showed distinct and predictable characteristics, closely matching the computational predictions.

Analysis of Virtual Contact Line Length ($L_{\xi}$): The length of the contact pattern along the virtual contact line direction was measured and compared with the value predicted from the calculated $\Delta K_{x\xi}$. The results, shown in Table 3, demonstrate excellent agreement, validating the fundamental relationship $\Delta K_{x\xi} \propto 1 / L_{\xi}^2$.

| Test Case | Calculated $L_{\xi}$ (mm) | Measured $L_{\xi}$ (mm) |

|---|---|---|

| A | ~12.5 | ~12.8 |

| B | ~12.5 | ~12.3 |

| C | ~15.5 | ~15.0 |

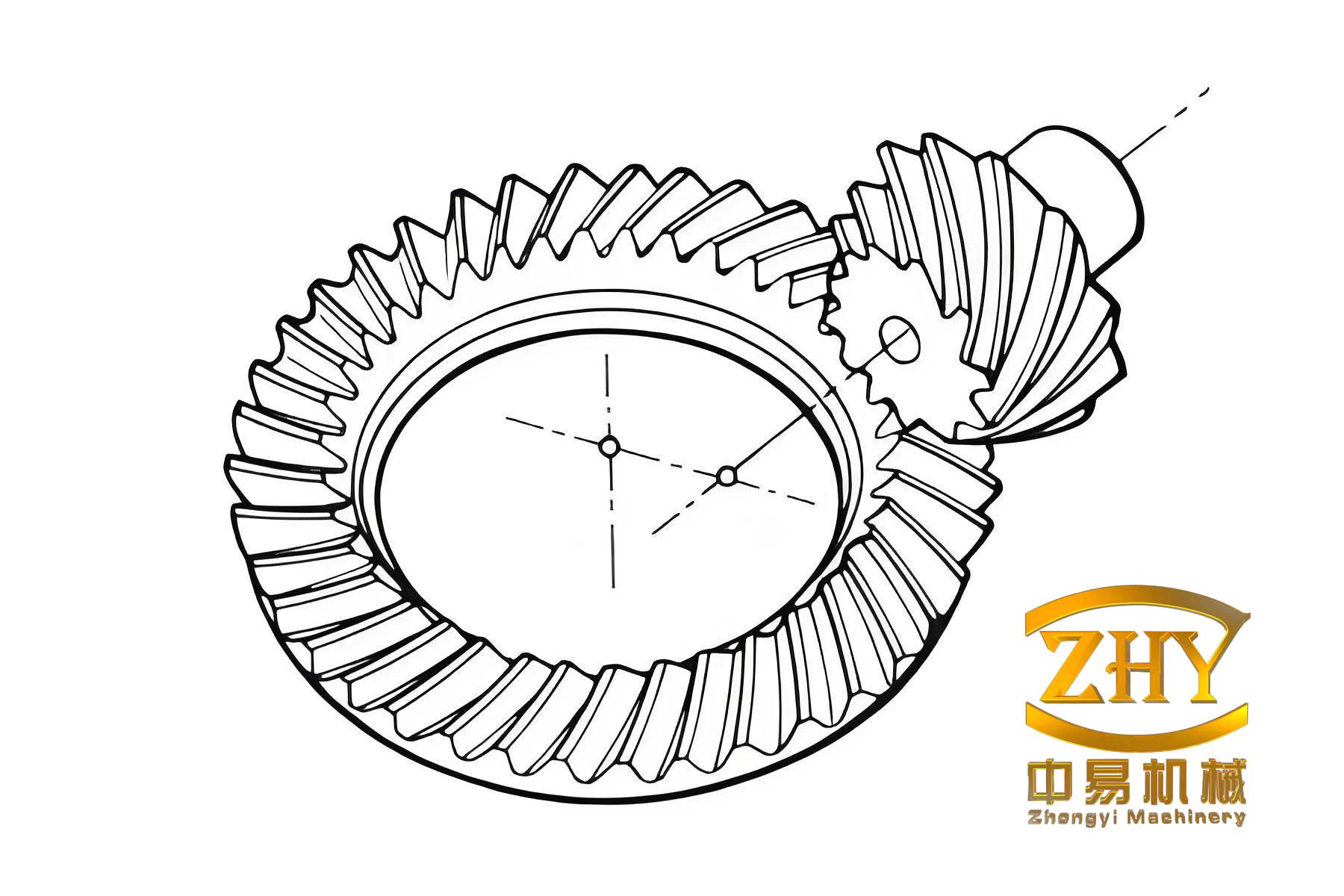

A critical observation from the calculations is the direct and strong influence of the $\Delta K_{x\xi}$ value on the required cutter point diameter for the hypoid pinion. As shown in Table 2 and Figure 1 (conceptual plot), varying $\Delta K_{x\xi}$ while holding other factors constant causes a significant change in the cutter point diameter. This refutes the conventional simplistic view that cutter diameter only affects lengthwise curvature. For a hypoid gear, where the angle $\alpha$ between the virtual contact line $\mathbf{\xi}$ and the face width $\mathbf{f}$ is significant (often around 30°), $\Delta K_{x\xi}$ impacts curvature in both the face width and profile directions. This influence diminishes for spiral bevel gears (smaller $\alpha$) and is zero for straight bevel gears ($\alpha = 0$).

Analysis of Path of Contact Direction ($\beta$): The orientation of the contact pattern, defined by angle $\beta$, was also measured and compared with the calculation. The results in Table 4 confirm that the chosen $\mathbf{\zeta}_g$ direction on the gear successfully translated into the intended path on the pinion.

| Test Case | Calculated $\beta$ (deg) | Measured $\beta$ (deg) |

|---|---|---|

| A | ~90° | ~88° |

| B | ~60° | ~62° |

| C | ~45° | ~47° |

The contact pattern characteristics varied significantly with $\beta$:

- Case A ($\beta \approx 90°$): The path of contact was nearly perpendicular to the face width direction. The contact pattern appeared as a narrow band across the tooth, resembling an “I” shape. Load transmission relies heavily on the tooth profile, resulting in a lower contact ratio and higher contact stress. It is also difficult to achieve toe/heel relief in this configuration for hypoid gears.

- Case B ($\beta \approx 60°$): The path was more diagonal. The contact pattern was more uniform and elliptical. While load distribution improves, controlling the lengthwise size can be challenging, often resulting in a long pattern, though toe/heal relief is easier to achieve.

- Case C ($\beta \approx 45°$): This represents a mild “inner diagonal” contact. The pattern utilizes both the profile and face width directions for load sharing, leading to a higher contact ratio. The size of the pattern in both directions is more easily controlled. Most well-designed hypoid gear pairs in practice exhibit contact patterns of this general type. The degree of diagonal can be adjusted via $\Delta K_{x\zeta}$ to fine-tune performance and noise.

A significant finding was that while controlling $\Delta K_{x\zeta}$ effectively shapes the pattern, setting it to zero (implying no modification along the path of contact) led to audible meshing impacts and increased noise, even if the static pattern looked acceptable. This underscores that contact pattern control and noise control, while related, are not identical. A comprehensive curvature modification strategy must address both.

4. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that precise control over the contact pattern of a hypoid gear pair is achievable through a fundamental understanding of its formation geometry and the strategic calculation of tooth surface curvature modifications. The key conclusions are:

- Effective Control Parameters: The position, shape, and size of the contact pattern can be effectively controlled by appropriately selecting the location of the contact reference point and the associated curvature modification values ($\Delta K_{x\xi}$, $\Delta K_{x\zeta}$, etc.) during the pinion cutting calculation process.

- Superior Methodology: The proposed methodology, which analyzes and determines modifications based on the virtual contact line ($\mathbf{\xi}$) and the path of contact ($\mathbf{\zeta}$) directions, provides a more direct and accurate representation of the contact mechanics than the traditional empirical approach of separate lengthwise and profile corrections. This can be termed a “Direct Tooth Contact Analysis” method.

- Optimal Path of Contact: For hypoid gears, selecting the path of contact direction to have an angle $\beta$ in the range of 40° to 50° (an inner diagonal orientation relative to the face width) generally facilitates better control over the contact pattern dimensions and promotes a higher contact ratio and smoother operation.

- Noise Consideration: Proper curvature modification is not only about achieving a visually acceptable static contact pattern but is also a critical factor in controlling gear meshing noise. The modification along the path of contact ($\Delta K_{x\zeta}$), linked to the transmission error curve, is particularly important for acoustic performance.

- Cutter Diameter Effect: A new insight is established: For hypoid gears, changing the pinion cutter point diameter directly and significantly influences the length of the virtual contact line ($L_{\xi}$), as it is the primary machine setting used to realize the calculated $\Delta K_{x\xi}$. This effect is modulated by the angle $\alpha$ between the contact line and the tooth face width.

- Manufacturing Implication: With this calculative approach, it is possible to obtain high-quality hypoid gears with predictable contact patterns on machine tools without relying on complex ratio-varying mechanisms during the cut, simplifying the manufacturing process.

In summary, a systematic approach to curvature modification, grounded in the differential geometry of gear surfaces and meshing kinematics, enables the rational design and predictable manufacture of high-performance, quiet hypoid gear pairs.