As a researcher deeply immersed in the field of advanced robotics and precision manufacturing, I have witnessed firsthand the relentless pursuit of more agile, powerful, and efficient machines. The recent global spotlight on humanoid robotics underscores a critical truth: the elegance and capability of these machines are a direct reflection of our mastery over core technologies in perception, control, materials, and actuation. At the very heart of a robot’s physical expression lies its joints—the mechanical analogues to our own shoulders, hips, and wrists. For decades, the industry has relied on a familiar set of solutions for these crucial components, but each comes with inherent trade-offs that ultimately limit robotic potential. Today, a paradigm shift is underway, propelled by a revolutionary mechanical concept: the spherical gear. This innovation promises to transcend the limitations of traditional reducers, offering a path toward truly biomimetic, compact, and high-performance robotic articulation. The concurrent advancements in this field, notably the independent development and mastery of spherical gear technology alongside its international counterparts, signal a pivotal moment of technological leapfrogging.

The landscape of robotic joint actuation has been dominated by several well-established types of speed reducers, each suited for specific niches but none offering a complete solution for the demanding requirements of next-generation humanoids. The table below summarizes their key characteristics and limitations:

| Reducer Type | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Precision Planetary Gear | Compact size, high single-stage efficiency, good load capacity, cost-effective. | Limited single-stage reduction ratio, requires maintenance, lower precision. | Industrial robot axes, general automation. |

| Harmonic Drive | Very high reduction ratio in compact package, excellent positional accuracy, zero backlash. | Limited torque capacity, finite fatigue life, sensitive to shock loads, higher cost. | Robot wrists, precision rotary stages, aerospace. |

| RV (Rotary Vector) Reducer | Very high rigidity and torque capacity, high reduction ratios, excellent durability. | Large size and weight, complex manufacturing, high cost. | Robot base and arm joints requiring high strength. |

| Enveloping Worm Gear | High torque density, compact design, self-locking capability, low noise. | Lower transmission efficiency, typically limited to 90° output, requires additional gearing for other axes. | Packaging machinery, lifts, where self-locking is needed. |

The fundamental shortcoming common to all these designs is their single-degree-of-freedom (DoF) output. A robotic joint, much like a human shoulder or hip, inherently requires movement in two rotational axes (e.g., pitch and yaw) to achieve natural motion. To replicate this with conventional technology, engineers must stack two single-DoF reducers orthogonally. This approach inevitably leads to bulky, heavy, and complex assemblies. The compounded inertia, friction losses, and heat generation from two separate motor-reducer systems become significant bottlenecks for dynamic performance, energy efficiency, and miniaturization—goals paramount for humanoid robots that must operate in human-centric environments.

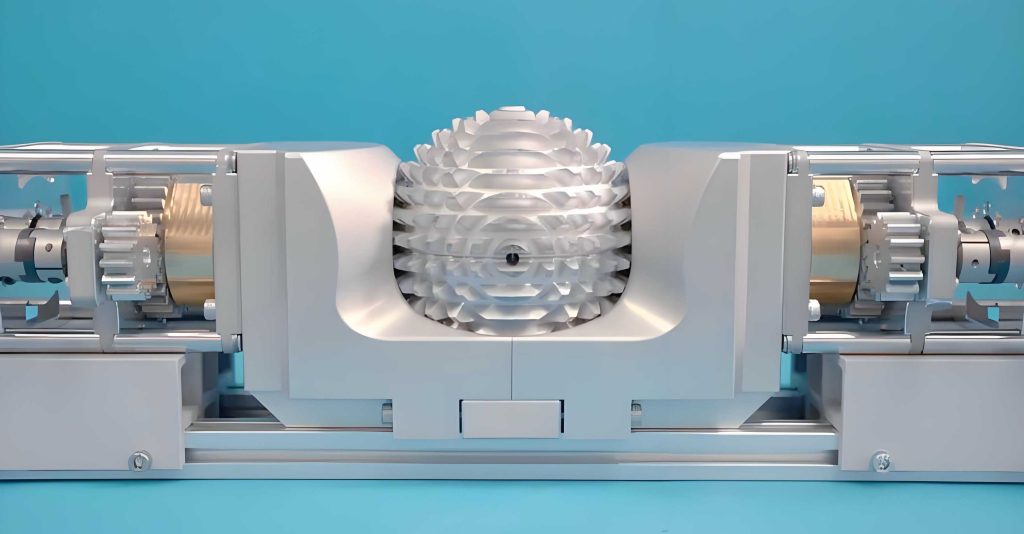

This is where the spherical gear mechanism represents a true breakthrough. Unlike traditional gears that transmit motion between parallel or intersecting shafts via cylindrical or conical tooth forms, the spherical gear operates on an entirely different principle. It is a complex three-dimensional mechanism designed to provide two rotational degrees of freedom directly from a single, compact assembly. Conceptually, it mimics the ball-and-socket joint of the human body but with fully constrained, precisely controlled motion driven by input from two actuators.

The core of the mechanism involves intricate, spatially curved tooth profiles meshing on spherical surfaces. This design allows the output member to tilt and swivel freely within a conical workspace. The kinematics can be described by relating the input rotations (typically from two coaxial motors via a differential system) to the two output angles (e.g., $\theta$ and $\phi$). A simplified kinematic model might represent the output orientation as a function of the input shaft angles $\alpha$ and $\beta$ through a set of non-linear equations derived from spherical trigonometry and the specific gear geometry:

$$ \mathbf{R}_{output} = f(\alpha, \beta; G) $$

where $\mathbf{R}_{output}$ is the rotation matrix of the output socket and $G$ represents the fixed geometric parameters of the spherical gear pair. The transmission ratio is not constant but varies across the workspace, a characteristic that must be expertly managed in the control system.

The advantages of this approach are transformative, especially for humanoid robotics:

| Feature | Benefit | Impact on Humanoid Design |

|---|---|---|

| Dual-DoF Direct Output | Eliminates the need for stacking two reducers. Enables direct, simultaneous control of pitch and yaw. | Dramatically reduces joint size and weight. Simplifies mechanical design and assembly. |

| High Torque Density | Distributes contact forces over complex curved surfaces, allowing high torque transmission in a small volume. | Enables powerful, compact joints for limbs and torso, crucial for dynamic motion and payload capacity. |

| Compact & Lightweight | Inherently integrated design removes redundant housings and structural supports. | Reduces overall robot mass, improving energy efficiency and dynamic response (lower inertia). |

| Potential for High Rigidity | Multi-point contact on a spherical surface can provide excellent torsional stiffness. | Improves positional accuracy and stability during high-force interactions or impacts. |

| Biomimetic Motion | Motion pattern closely resembles a biological ball-and-socket joint. | Facilitates more natural, human-like movement trajectories and grace. |

However, the revolutionary potential of the spherical gear is matched by its formidable engineering challenges. The barriers to realization are primarily in three domains: Design & Analysis, Precision Manufacturing, and Integrated Control.

1. Design and Kinematic/Dynamic Analysis: The tooth profile of a spherical gear is not a simple involute. It is a complex 3D space curve that must be designed to ensure continuous, smooth meshing across the entire range of motion without interference or jamming. This requires advanced geometric modeling and simulation. Contact mechanics become highly non-linear. The contact force $\mathbf{F}_c$ between teeth is a function of the instantaneous orientation, load torque $\tau$, and the local surface curvatures:

$$ \mathbf{F}_c = g(\theta, \phi, \tau, \kappa_1, \kappa_2) $$

where $\kappa_1$ and $\kappa_2$ are principal curvatures of the mating surfaces. Predicting wear, efficiency (which can be modeled as $\eta = P_{out}/P_{in}$ where power losses stem from sliding friction), and lifetime demands sophisticated multi-body dynamics software and tribological studies.

2. Precision Manufacturing: This is arguably the most significant hurdle. Machining the intricate, hardened, and micron-accurate 3D contours of a metal spherical gear is an extreme challenge for conventional machine tools. It is a task uniquely suited for high-precision 5-axis computer numerical control (CNC) machining centers. The toolpath generation for such a part is extraordinarily complex, requiring simultaneous and synchronized movement along five axes ($X$, $Y$, $Z$, and two rotational axes $A$ and $C$) to keep the cutting tool normal to the constantly changing surface geometry. The volumetric accuracy and repeatability of the machine tool directly dictate the performance of the final spherical gear assembly. The manufacturing equation is one of extreme precision:

$$ \text{Final Gear Accuracy} \propto f(\text{CNC Volumetric Error}, \text{Toolpath Algorithm}, \text{Thermal Stability}, \text{Tool Wear}) $$

Mastering the manufacturing of the spherical gear, therefore, implies mastery at the pinnacle of “mother machine” technology—the advanced 5-axis CNC mill.

3. Integrated Control System: Controlling a dual-DoF joint driven by two motors through a differential and a non-linear spherical gear transmission is non-trivial. The control system must account for kinematic coupling, variable transmission ratios, and potential non-linear friction effects. A sophisticated servo control law is required. For a desired output torque vector $\vec{\tau}_{d} = (\tau_{\theta}, \tau_{\phi})$, the controller must calculate the required motor currents $\vec{I}_{m}$, compensating for the mechanism’s dynamics:

$$ \vec{I}_{m} = \mathbf{J}^{-T}(\theta, \phi) \cdot \vec{\tau}_{d} + \text{Compensation}(\dot{\theta}, \dot{\phi}, \text{friction, inertia}) $$

where $\mathbf{J}$ is the Jacobian matrix mapping motor space to output space, which varies with joint position. This demands a powerful, real-time “cloud-native” or embedded CNC/robotic controller capable of executing complex algorithms.

The recent, nearly simultaneous progress in Japan and the independent, parallel breakthrough achieved domestically mark a historic convergence. It demonstrates that the underlying principles of the spherical gear are recognized globally as the next frontier. The domestic achievement is particularly significant because it represents a full-stack mastery—from the core design theory and proprietary 5-axis CNC technology needed to manufacture it, to the advanced control systems required to bring it to life. This vertical integration is a potent formula for innovation and rapid iteration.

The implications of this technology extend far beyond humanoid robotics. The unique capabilities of the spherical gear joint open doors across multiple high-tech sectors:

- Aerospace: For compact, dual-axis pointing mechanisms for satellite antennas, sensors, and solar array drives, where weight, reliability, and precision are critical.

- Medical & Assistive Devices: In advanced prosthetics and exoskeletons, providing patients with more natural and powerful joint movements.

- Semiconductor Manufacturing: In precision wafer handling and assembly equipment requiring delicate, multi-orientation manipulation in cleanroom environments.

- Advanced Industrial Automation: For complex assembly tasks where a compact, dexterous end-effector can replace multiple single-axis systems.

The path forward is one of refinement and integration. Research must focus on optimizing tooth profiles for minimal wear and maximum efficiency, experimenting with advanced materials (including composites and special polymers for specific applications), and further miniaturizing the overall joint package. The development of standardized, modular spherical gear joint units will be key to widespread adoption. Furthermore, seamless integration with high-torque-density motors and embedded sensors (torque, position) will create truly intelligent, plug-and-play actuator modules.

In conclusion, the advent of the practical spherical gear joint is not merely an incremental improvement; it is a fundamental re-architecting of robotic articulation. It directly addresses the critical shortcomings of mass, volume, complexity, and kinematic naturalness that have constrained robot design for years. The fact that this core technology has been independently grasped and is being propelled toward industrialization signifies a major strategic advancement. It moves the field from imitation to innovation, providing a foundational technology upon which a new generation of agile, efficient, and truly capable robots—especially humanoids—can be built. The race is no longer about assembling known components better, but about leveraging breakthroughs like the spherical gear to redefine what is mechanically possible. This is the new height of robotic articulation technology, and it is a frontier now being actively charted.