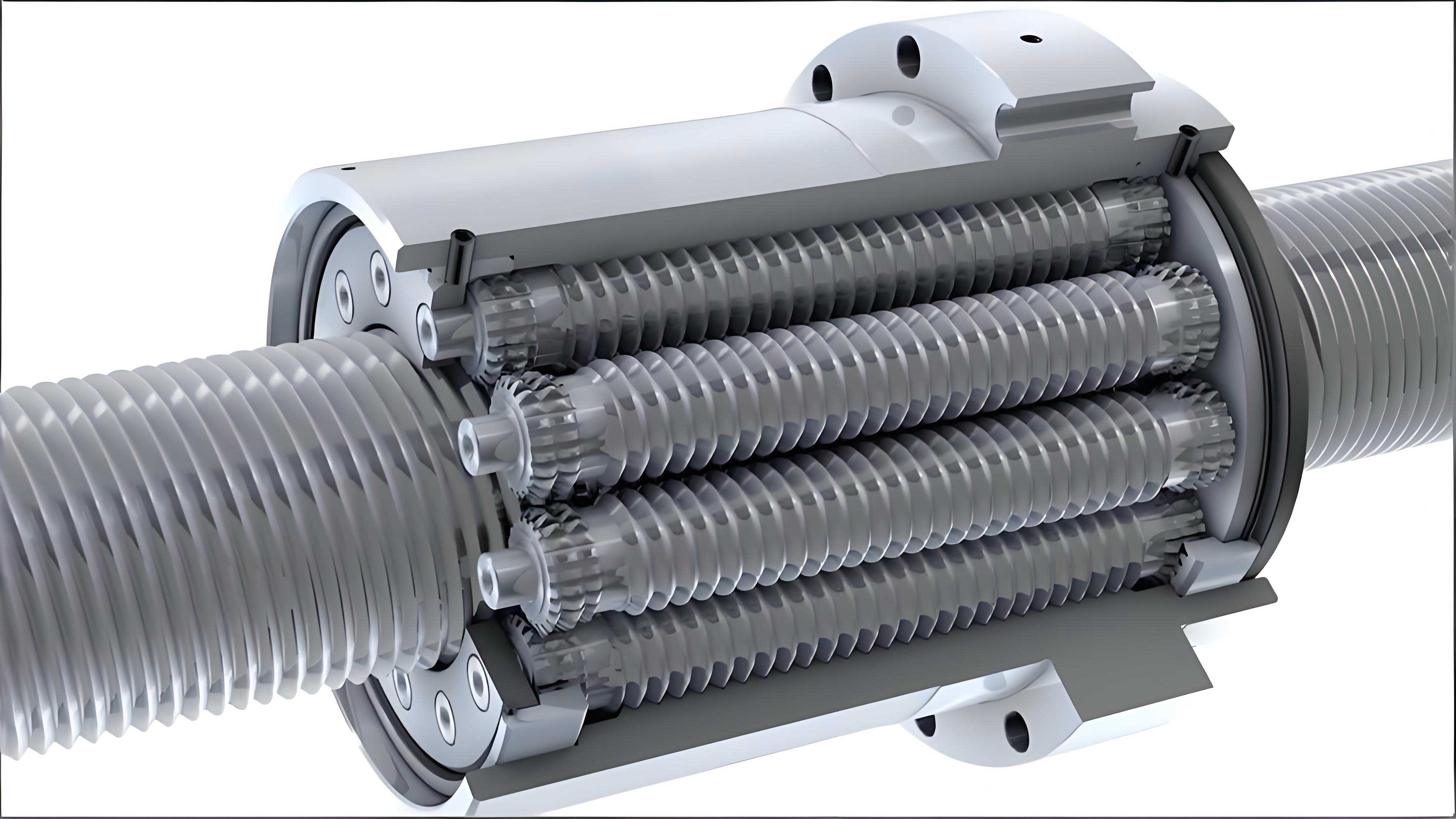

The planetary roller screw assembly represents a pivotal advancement in power-dense, precision linear motion systems. Its superior load capacity, longevity, and accuracy have cemented its role in demanding applications across aerospace, marine, heavy machinery, and industrial automation. The fundamental operation relies on the meshing engagement between the threads of the screw, the planetary rollers, and the nut, transmitting motion and force through rolling contact. Consequently, the load distribution across these interacting threads is a primary determinant of the assembly’s performance, influencing its static and dynamic stiffness, fatigue life, operational smoothness, and ultimate load-bearing capability. Non-uniform load sharing leads to premature wear, stress concentration, and potential failure of the most heavily loaded threads, thereby constraining the assembly’s full potential. This treatise delves into a comprehensive methodology for equalizing the load distribution, herein referred to as “load balance design,” which encompasses both optimal structural parameter selection at the design stage and precision control during manufacturing.

1. Foundational Design Criteria for Thread Parameters

Prior to exploring load equalization strategies, it is imperative to establish the fundamental design constraints for the thread geometry. The thread teeth must be designed to withstand operational loads without failure or permanent deformation. Two core criteria govern this: the thread tooth strength criterion and the contact yield criterion.

1.1 Thread Tooth Strength Criterion

The planetary roller screw assembly features point contacts between the screw, roller, and nut threads. The tooth flank in the vicinity of the contact point is subjected to bending and shear stresses. Modeling the engaged thread portion as a cantilever beam fixed at the thread root provides a basis for analysis. The length of the loaded segment for a thread on the screw, roller, or nut is given by the arc length corresponding to its engagement half-angle:

$$ l = \frac{2 \pi \beta_X R_X}{180} $$

where $\beta_X$ is the engagement half-angle for the respective component (screw, roller-nut side, or roller-screw side), and $R_X$ is its pitch radius. The shear strength condition at the thread root (section m-m) is:

$$ \tau = \frac{f_a}{c l} \leq [\tau] $$

The bending strength condition at the same critical section is:

$$ \sigma = \frac{6 f_a h_f}{c^2 l} \leq [\sigma_b] $$

In these equations, $f_a$ is the axial load on the thread tooth, $c$ is the thickness at the thread root, $h_f$ is the thread dedendum height, and $[\tau]$ and $[\sigma_b]$ are the allowable shear and bending stresses of the material, respectively.

1.2 Thread Contact Yield Criterion

To ensure the contact remains elastic and avoids plastic deformation that accelerates fatigue, the Hertzian contact stress must be below the yield limit. The classic Hertz theory for two elastic bodies in point contact provides the relationship between load $Q$, contact deflection $\delta$, and material/geometry parameters. The maximum compressive stress $\sigma_{max}$ occurs at the center of the contact ellipse. According to the von Mises yield criterion, yielding initiates sub-surface when the maximum orthogonal shear stress reaches a critical value. The condition to avoid plastic deformation can be derived, yielding the maximum permissible normal contact force $Q$:

$$ Q = \frac{2}{3} \pi a^* b^* \left( \frac{\sigma_s}{\sqrt{3} k_{st}} \right)^3 / (E’^2 \cdot \Sigma\rho^2 ) $$

where $\sigma_s$ is the material’s yield strength, $k_{st}$ is a coefficient related to the contact ellipse eccentricity (typically 0.30-0.33), $a^*$ and $b^*$ are Hertzian contact coefficients dependent on the principal curvatures, $E’$ is the equivalent elastic modulus, and $\Sigma\rho$ is the sum of principal curvatures. The corresponding axial force limit for the thread is:

$$ Q_{axial} = Q \cdot \cos\alpha_R \cdot \cos(\theta / 2) $$

where $\alpha_R$ is the roller helix angle and $\theta$ is the thread profile angle.

1.3 Rated and Ultimate Thread Load

Based on the above criteria, two critical load limits for a single thread tooth are defined. The Rated Load ($f_c$) is the maximum axial load a thread tooth can sustain without plastic contact deformation or strength failure, ensuring elastic operation and long life. The Ultimate Load ($f_{max}$) is the maximum axial load before strength failure (shear or bending), disregarding plastic deformation. They are calculated as:

$$ f_c = \min \left( Q_{axial},\ cl[\tau],\ \frac{c^2 l[\sigma_b]}{6h_f} \right) $$

$$ f_{max} = \min \left( cl[\tau],\ \frac{c^2 l[\sigma_b]}{6h_f} \right) $$

These values serve as benchmarks for evaluating the acceptability of the load distribution in a planetary roller screw assembly design.

1.4 Planetary Roller Screw Assembly Parameter Design Criterion

The load distribution pattern is a function of the assembly’s design parameters. A key metric is the Load Distribution Non-Uniformity Coefficient ($i_{Xj}$), defined as the ratio of the calculated load on the j-th thread to the average thread load:

$$ i_{Xj} = \frac{f_{Xj}}{f_{ave}} $$

Here, $X$ denotes $S$ for the screw side or $N$ for the nut side of the roller threads. The maximum value, $\max[i_{Xj}]$, quantifies the severity of load concentration. A successful load balance design must satisfy the condition that the most heavily loaded thread does not exceed its capacity:

$$ \max[i_{Xj}] \cdot f_{ave} \leq f_{max} $$

Since $\max[i_{Xj}]$, $f_{ave}$, and $f_{max}$ are all interdependent functions of the design parameters, the design process becomes an iterative optimization balancing load distribution, overall dimensions, and strength.

2. Load Equalization through Structural Parameter Design

The selection of geometric parameters fundamentally influences the stiffness chain within the planetary roller screw assembly and hence the load distribution. This section analyzes the impact of key parameters, guiding their optimization for load equalization. The analysis is based on a representative planetary roller screw assembly with a 15 kN load capacity.

The core principle is that non-uniform load distribution stems primarily from the cumulative axial deflections of the screw and nut shaft sections under load. Thread contact and bending deflections are localized. Therefore, achieving uniform load distribution requires the careful matching of shaft section stiffnesses among the screw, rollers, and nut to favorably compensate for these deflections.

2.1 Screw-to-Roller Diameter Ratio ($k$) and Number of Rollers ($z$)

The screw-to-roller pitch diameter ratio, $k = d_S / d_R$, is intrinsically linked to the screw thread starts $n_S$ and the maximum possible number of rollers $z_{max}$:

$$ k = n_S – 2 $$

This ratio critically affects the relative shaft stiffness between the screw and the rollers. The shaft stiffness ratio is proportional to the fourth power of the diameter. Therefore, increasing $k$ significantly increases the screw’s stiffness relative to a single roller.

| $k$ | Screw Starts ($n_S$) | Max Rollers ($z_{max}$) | Approx. Screw/Roller Stiffness Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | 5 | 2 / $z$ |

| 2 | 4 | 9 | 8 / $z$ |

| 3 | 5 | 12 | 18 / $z$ |

| 4 | 6 | 15 | 32 / $z$ |

Analysis reveals that as $k$ increases (or as the number of rollers $z$ increases for a given $k$), the load distribution becomes less uniform on both the screw and nut sides. A higher $k$ or more rollers reduces the relative stiffness of the roller set compared to the screw, diminishing their ability to equalize load. However, a greater number of rollers reduces the average load per thread, potentially benefiting overall life. The design choice involves a trade-off between load distribution quality, radial size ($k$ affects helix angles and nut size), and total load-sharing capability. The goal is to select a $k$ value that meets installation and transmission requirements, then optimize other parameters for load equalization.

2.2 Lead ($P$)

The lead is a primary thread parameter, dictating other profile dimensions. Its selection profoundly affects load distribution and manufacturing cost/complexity.

Increasing the lead, while keeping diameters constant, reduces the cross-sectional area of the screw and nut threads, thereby reducing their axial shaft stiffness. Analysis shows that as lead increases, load distribution deteriorates significantly. The non-uniformity coefficient range widens considerably. Furthermore, for larger leads, the load distribution on the nut side often develops a distinct “high-low-high” pattern across the engaged threads. This phenomenon occurs because reduced shaft stiffness in both screw and nut amplifies the interaction between loads on opposite sides of a roller. The nut side, typically stiffer than the screw, shows greater sensitivity to this interaction, manifesting the bimodal pattern. Therefore, for load equalization, a smaller lead is generally preferable, provided it meets the strength criteria and manufacturing constraints.

2.3 Number of Threads per Roller ($n$)

The number of engaged threads on each roller directly affects load distribution and average thread load. While increasing $n$ spreads the total load over more teeth, it also exacerbates load non-uniformity due to the cumulative effect of shaft deflections.

Analysis indicates that the load distribution on both sides becomes progressively more non-uniform as $n$ increases, with the screw side being more sensitive. Beyond a certain count (e.g., n > 26 in the studied case), the “high-low-high” pattern emerges on the nut side. Conversely, a very small $n$ results in excessively high average load per thread, risking overstress. The design must strike a balance by ensuring the condition $\max[i_{Xj}] \cdot f_{ave} \leq f_c$ is satisfied, where $f_{ave} = F_{axial} / (z \cdot n)$.

2.4 Nut Outer Diameter ($D_{out}$)

The nut’s outer diameter governs its axial shaft stiffness. A larger diameter increases stiffness. Analysis shows that the screw-side load distribution is largely unaffected by $D_{out}$. However, the nut-side distribution becomes more uniform as $D_{out}$ increases, up to a point. Beyond a certain threshold, the nut becomes so stiff that its deformation is minimal, making the load distribution on its side highly sensitive to the interacting deformation from the screw side, again leading to the “high-low-high” pattern.

The key insight is that the nut’s shaft stiffness should be commensurate with the screw’s stiffness. An excessively stiff nut does not necessarily lead to better overall load equalization and may hinder later corrective measures via precision control. The design should target a nut outer diameter that brings its axial stiffness into a similar order of magnitude as the screw’s stiffness.

| Parameter | Trend (Increase) | Effect on Load Distribution | Guideline for Load Balance Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| Screw-to-Roller Ratio ($k$) | Increase | Increases non-uniformity on both sides. | Choose based on transmission needs, then compensate with other parameters. Avoid unnecessarily high $k$. |

| Number of Rollers ($z$) | Increase | Increases non-uniformity but lowers average thread load. | Select to balance load-sharing capability and distribution quality. |

| Lead ($P$) | Increase | Significantly increases non-uniformity; can cause bimodal pattern. | Prefer smaller leads to enhance shaft stiffness and distribution uniformity. |

| Threads per Roller ($n$) | Increase | Increases non-uniformity, especially on screw side. | Optimize to satisfy $ \max[i_{Xj}] \cdot f_{ave} \leq f_c$; avoid very high counts. |

| Nut Outer Diameter ($D_{out}$) | Increase | Initially makes nut-side distribution more uniform; after a threshold, causes bimodal pattern. | Design so nut shaft stiffness is comparable to screw stiffness. |

3. Load Equalization through Precision and Tolerance Design

Even with optimally chosen parameters, manufacturing imperfections, primarily pitch deviations, can severely disrupt load distribution. However, this sensitivity can be harnessed through active precision design—controlling not just the magnitude of errors but also their systematic pattern (tolerance zone placement) to pre-compensate for elastic deformations.

3.1 Control of Pitch Accuracy

Pitch errors alter the initial contact state of the threads. Under load, threads with positive pitch error (locally longer lead) engage earlier and carry more load, while those with negative error carry less. The sensitivity of load distribution to pitch error increases with the shaft stiffness of the components. For a stiff planetary roller screw assembly (large screw diameter or fine lead), even small pitch errors can cause significant load fluctuation.

Simulations with random pitch errors following different normal distributions $N(\mu, \sigma^2)$ on the rollers demonstrate this effect. With errors obeying $N(0, 0.25^2)$, load distribution resembles the ideal (error-free) pattern with mild fluctuation. Under $N(0, 1^2)$, fluctuation increases, worsening non-uniformity. Under $N(0, 1.5^2)$, the fluctuation becomes severe, with some threads severely underloaded and others overloaded, potentially inverting the overall distribution trend.

Therefore, stringent control of pitch accuracy is mandatory. The required precision level is inversely related to the shaft stiffness: assemblies with higher stiffness require tighter pitch tolerances.

3.2 Active Tolerance Zone Placement

The paradigm shifts from merely minimizing errors to strategically assigning them. By intentionally offsetting the pitch tolerance zones for the screw, rollers, and nut, the initial “gap” distribution between threads can be engineered to counteract the anticipated elastic deformations under load, thereby promoting uniform final contact.

For instance, if analysis predicts that under load the screw shaft stretches and the nut compresses axially, the threads near the ends of the engagement zone will tend to separate slightly more than those in the middle. To compensate, one can specify the roller pitch (on the screw side) to have a systematic positive deviation trend from one end to the other, and the nut pitch to have a corresponding compensatory deviation. This ensures that when the assembly is loaded, all threads come into contact more simultaneously.

A practical method involves calculating the axial compression/elongation of the screw and nut shafts at rated load. This total deformation $\Delta L$ is distributed along the engaged length. The pitch deviation for the $j$-th thread on a component can be specified as a function of its position to offset this deformation. For example, a linear correction profile could be:

$$ \delta P_{component}(j) = C \cdot \left( \frac{j}{n} – 0.5 \right) $$

Where $C$ is a coefficient determined from $\Delta L$ and the stiffness relationships. The sign and magnitude of $C$ differ for the screw, roller (screw side), roller (nut side), and nut. The screw lead accuracy must remain very high to preserve the system’s kinematic accuracy, while the roller and nut pitches can be more actively adjusted for load equalization.

Simulation confirms that with actively designed pitch errors (e.g., roller screw-side errors following $N(+0.15, 0.25^2)$ and nut-side errors following $N(+0.075, 0.25^2)$), the load distribution can be dramatically improved, yielding a near-uniform pattern with a very narrow non-uniformity coefficient range (e.g., [0.98, 1.02] on the nut side).

4. Conclusion

A holistic methodology for the load balance design of planetary roller screw assemblies has been presented, integrating structural parameter optimization and precision/tolerance control.

- Design Criteria: Thread parameters must satisfy strength and contact yield criteria, defining the rated ($f_c$) and ultimate ($f_{max}$) thread loads. The overarching design criterion is $\max[i_{Xj}] \cdot f_{ave} \leq f_{max}$, ensuring no thread is overloaded.

- Parameter Design for Equalization: The primary goal of parameter optimization is to achieve a favorable matching of the axial shaft stiffnesses of the screw, the roller set, and the nut. Key guidelines include:

- Prefer moderate screw-to-roller diameter ratios ($k$).

- Select leads that provide adequate screw/nut shaft stiffness.

- Optimize the number of roller threads to balance average load and distribution uniformity.

- Design the nut outer diameter so its stiffness is on the same order as the screw’s stiffness.

- Precision and Tolerance Design for Equalization: Load distribution is highly sensitive to pitch errors, especially in stiff assemblies.

- Tighter pitch accuracy is required for assemblies with higher shaft stiffness (larger diameters, finer leads).

- Active tolerance zone placement, based on predicted elastic deformations under load, is a powerful technique to equalize load distribution. By specifying systematic pitch deviations for rollers and the nut, the initial contact gaps can be pre-compensated, leading to remarkably uniform load sharing under operational conditions.

The synergistic application of these two pillars—thoughtful structural design informed by stiffness analysis and strategic precision control—enables the realization of planetary roller screw assemblies that fully utilize their material potential, delivering superior load capacity, extended service life, and reliable performance in the most demanding applications. The pursuit of optimal load balance is thus central to advancing the performance frontier of these critical mechanical components.