In the pursuit of advanced energy dissipation devices for structural vibration control, I have focused on harnessing the synergistic potential of electromagnetic principles and mechanical amplification. This research introduces and thoroughly investigates a novel damper configuration: the Eddy Current Damper with Rack and Pinion Gear transmission (ECD-RPG). The core innovation lies in integrating a rack and pinion gear system with a non-contact eddy current damping mechanism, creating a device that offers unique force characteristics, including significant apparent mass effects and velocity-proportional damping. The primary motivation stems from the limitations of traditional dampers in handling multi-directional seismic inputs and their associated maintenance needs. The proposed ECD-RPG aims to provide a robust, low-maintenance solution with adaptable force output. Throughout this article, I will detail the conceptual design, theoretical foundation, finite element analysis, and experimental validation of a prototype, consistently emphasizing the critical role of the rack and pinion gear in achieving the desired mechanical transformation and performance.

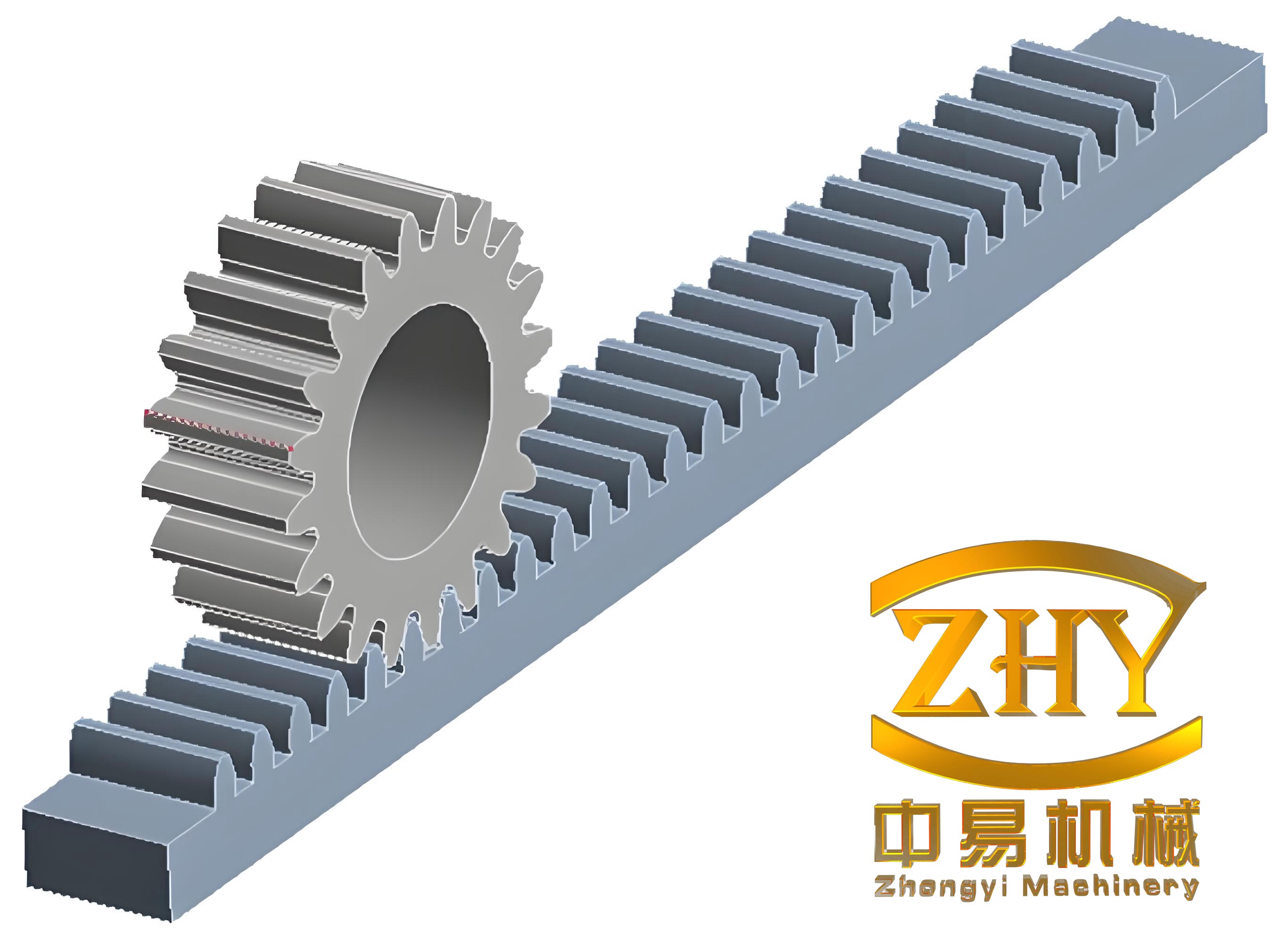

The fundamental operating principle of the ECD-RPG revolves around converting linear structural motion into rotational motion within the damper, thereby enabling the generation of both inertial and damping forces. The rack and pinion gear assembly is the indispensable component that facilitates this conversion. A typical system involves a linear rack that meshes with a pinion gear. When the rack moves linearly due to structural vibration, it causes the pinion to rotate. This simple yet effective rack and pinion gear mechanism can be extended to multi-stage gear trains to achieve specific amplification ratios. In my damper design, this conversion is pivotal for two reasons: first, it allows the use of a compact rotational eddy current damper unit; second, it introduces a gear ratio that amplifies the rotational speed and acceleration, directly influencing the equivalent inertia and damping forces perceived at the structural connection point.

The complete damper system, as I conceptualized it, consists of two main subsystems. The first is the motion translation subsystem built around the rack and pinion gear. It includes a primary rack connected to the structure, a first-stage pinion, a coaxial secondary gear, a third gear meshing with the secondary one, and finally a shaft that carries the conductive rotor. The rack is mounted perpendicular to a sliding guide rail. This specific geometric arrangement is crucial for decomposing arbitrary horizontal structural motions. The second subsystem is the energy dissipation unit, comprising permanent magnets arranged in a Halbach array or similar configuration, a conductive plate (typically copper or aluminum) attached to the rotor, and a back iron to enhance the magnetic circuit. When the rotor spins due to the rack and pinion gear action, the relative motion between the magnets and the conductor induces eddy currents in the latter, generating a damping torque that opposes the motion.

To address the challenge of multidirectional seismic excitation, I devised a motion decomposition strategy. The arbitrary horizontal motion of a building, denoted by a velocity vector $\vec{u}$, can be resolved into two orthogonal components. The ECD-RPG is designed to be sensitive primarily to the component aligned with its rack’s axis. If two such dampers are installed orthogonally on a structure, as one would with typical bracing systems, the combined system can effectively control motion in any horizontal direction. The rack and pinion gear system in each damper engages only with the motion component parallel to its orientation. For a structural motion at an angle $\alpha$ to the rack’s axis, the effective linear velocity $V$ input to the rack and pinion gear is given by:

$$ V = \dot{u} \cos \alpha $$

where $\dot{u}$ is the magnitude of the structural velocity. This cosine dependence fundamentally affects the force output, as will be derived theoretically. The component perpendicular to the rack is accommodated by the sliding rail, ensuring no binding occurs. This elegant solution, enabled by the independent action of the rack and pinion gear and sliding rail, overcomes the jamming issues common in dampers with fixed axial directions.

The theoretical force output of the ECD-RPG is derived from energy principles and the dynamics of the rotating system. Let the radii of the first pinion, secondary gear, and third gear be $r_1$, $r_2$, and $r_3$, respectively. The angular velocity $\dot{\theta}$ of the conductive rotor is related to the rack velocity $V$ by the overall gear ratio:

$$ \dot{\theta} = \left( \frac{r_2}{r_1 r_3} \right) V = \left( \frac{r_2}{r_1 r_3} \right) \dot{u} \cos \alpha $$

The total torque $T_s$ on the rotor shaft is the sum of the inertial torque and the eddy current damping torque:

$$ T_s = J \ddot{\theta} + T_e(\dot{\theta}) $$

Here, $J$ is the total mass moment of inertia of the rotating parts (conductor and back iron), and $T_e$ is the eddy current damping torque, which is generally a function of angular velocity $\dot{\theta}$. For many configurations and moderate speeds, it can be approximated as linear: $T_e = c_\theta \dot{\theta}$, where $c_\theta$ is the rotational damping coefficient. By equating the input power from the structural force $F$ to the output power at the rotor, we have:

$$ F \dot{u} = T_s \dot{\theta} $$

Substituting the expressions for $\dot{\theta}$ and $T_s$ into the power balance equation yields the force $F$ applied to the structure in the direction of its motion:

$$ F = J \left( \frac{r_2}{r_1 r_3} \cos \alpha \right)^2 \ddot{u} + T_e(\dot{\theta}) \left( \frac{r_2}{r_1 r_3} \cos \alpha \right) \frac{1}{\dot{u}} $$

This can be simplified to a more recognizable form:

$$ F = m_e \ddot{u} + c_e \dot{u} $$

where $m_e$ is the apparent mass or inertance, and $c_e$ is the equivalent viscous damping coefficient as perceived at the structural level. Their expressions are:

$$ m_e = J \left( \frac{r_2}{r_1 r_3} \right)^2 \cos^2 \alpha $$

$$ c_e = \frac{T_e(\dot{\theta})}{\dot{\theta}} \left( \frac{r_2}{r_1 r_3} \right)^2 \cos^2 \alpha = c_\theta \left( \frac{r_2}{r_1 r_3} \right)^2 \cos^2 \alpha $$

The moment of inertia $J$ for a solid annular disc (the common shape for the rotor) is $J = \frac{1}{2} m_c (R^2 + r^2)$, where $m_c$ is the physical mass of the rotor, and $R$ and $r$ are its outer and inner radii. The factor $\cos^2 \alpha$ is critical, showing that both the inertial and damping forces are maximized when the structure moves parallel to the rack ($\alpha=0$) and are zero when motion is perpendicular ($\alpha=90^\circ$). The gear ratio term $\left( \frac{r_2}{r_1 r_3} \right)^2$ demonstrates the quadratic amplification of both apparent mass and damping due to the rack and pinion gear transmission. This is the key advantage: a relatively small physical rotating mass can produce a very large apparent mass $m_e$, potentially orders of magnitude larger, enhancing its inertia-based control force. Furthermore, mechanical friction $f_0$ within the rack and pinion gear assembly and bearings must be accounted for, leading to the complete mechanical model:

$$ F = m_e \ddot{u} + c_e \dot{u} + f_0 \cdot \text{sgn}(\dot{u}) $$

This model represents a parallel combination of an inerter (providing force proportional to acceleration) and a damper (providing force proportional to velocity), a unique characteristic enabled by the rack and pinion gear system.

To validate these theoretical concepts, I designed and fabricated a reduced-scale prototype of the ECD-RPG. The primary goal was to measure the apparent mass $m_e$ and the damping coefficient $c_e$ experimentally and compare them with theoretical and simulation predictions. The prototype’s rack and pinion gear system had the following specifications: the first pinion radius $r_1 = 32$ mm, the secondary gear radius $r_2 = 96$ mm, and the third gear radius $r_3 = 16$ mm. This gives a gear ratio factor $r_2/(r_1 r_3) = 96/(32 \times 16) = 0.1875$ mm$^{-1}$. The conductive rotor was a copper disc with an outer radius $R = 100$ mm, an inner radius $r = 10$ mm, and a variable thickness $t_c$. Its physical mass $m_c$ depended on thickness. For instance, for a 2 mm thick copper disc, $m_c \approx 4.89$ kg. The permanent magnets were NdFeB blocks, $30 \times 30 \times 10$ mm, with their magnetization direction aligned appropriately. The air gap between the magnets and the conductor was set to 4 mm. The entire assembly was mounted on a rigid base.

The experimental setup involved fixing the damper’s base and connecting its rack to an electro-mechanical actuator capable of imposing harmonic displacements. The actuator’s displacement $u(t)$ was measured with a laser displacement sensor, and the force $F(t)$ at the rack-structure interface was measured with a load cell. The tests consisted of applying harmonic motion $u(t) = A \sin(2\pi f t)$ with a fixed amplitude $A = 50$ mm and varying the frequency $f$ from 0.10 Hz to 0.48 Hz. Tests were conducted for two loading angles: $\alpha = 0^\circ$ (optimal) and $\alpha = 45^\circ$, to verify the $\cos^2 \alpha$ dependence. For each configuration, tests were run both with and without the permanent magnets installed to isolate the inertial and damping components.

From the harmonic input, the velocity and acceleration are $\dot{u} = 2\pi f A \cos(2\pi f t)$ and $\ddot{u} = -4\pi^2 f^2 A \sin(2\pi f t)$. The theoretical force output becomes:

$$ F(t) = -4m_e\pi^2 f^2 A \sin(2\pi f t) + 2c_e\pi f A \cos(2\pi f t) + f_0 \cdot \text{sgn}(\dot{u}) $$

By analyzing the measured force-displacement hysteresis loops, the amplitude of the inertial force $Q_{ia}$ (from tests without magnets) and the damping force amplitude $Q_{da}$ (from the difference in loops with and without magnets) can be extracted. They relate to the parameters as:

$$ Q_{ia} = 4 m_e \pi^2 f^2 A $$

$$ Q_{da} = 2 c_e \pi f A $$

These equations allow for the experimental determination of $m_e$ and $c_e$ from the slope of $Q_{ia}$ versus $f^2$ and $Q_{da}$ versus $f$, respectively.

The theoretical apparent mass for $\alpha=0^\circ$ is calculated first. Using $J = \frac{1}{2} \times 4.89 \times (0.1^2 + 0.01^2) = 0.0247$ kg·m² and the gear ratio factor $0.1875$ mm$^{-1}$ = $187.5$ m$^{-1}$, we get:

$$ m_e = J \left( \frac{r_2}{r_1 r_3} \right)^2 = 0.0247 \times (187.5)^2 \approx 868 \text{ kg} $$

For $\alpha=45^\circ$, $m_e$ is multiplied by $\cos^2 45^\circ = 0.5$, yielding approximately $434$ kg. These are the theoretical benchmarks. The experimental results for the inertial force amplitude across different frequencies are summarized in Table 1, along with the derived apparent mass.

| Loading Angle $\alpha$ | Frequency $f$ (Hz) | Acceleration Amplitude $\ddot{u}_a$ (m/s²) | Inertial Force Amplitude $Q_{ia}$ (N) (Experimental) | Apparent Mass $m_e$ (kg) (Experimental) | Theoretical $m_e$ (kg) | Relative Error |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0° | 0.10 | 0.020 | 35.5 | 887.5 | 868 | +2.2% |

| 0.20 | 0.079 | 136.2 | 861.4 | 868 | -0.8% | |

| 0.30 | 0.178 | 299.0 | 840.3 | 868 | -3.2% | |

| 0.40 | 0.316 | 521.0 | 824.1 | 868 | -5.1% | |

| 0.48 | 0.455 | 766.8 | 842.3 | 868 | -3.0% | |

| 45° | 0.10 | 0.020 | 16.8 | 420.0 | 434 | -3.2% |

| 0.20 | 0.079 | 66.5 | 420.6 | 434 | -3.1% | |

| 0.30 | 0.178 | 145.2 | 408.1 | 434 | -6.0% | |

| 0.40 | 0.316 | 252.0 | 398.6 | 434 | -8.2% | |

| 0.48 | 0.455 | 370.0 | 406.6 | 434 | -6.3% |

The data shows good agreement between experimental and theoretical apparent mass values. The small discrepancies, typically within 8%, can be attributed to factors like slight misalignments in the rack and pinion gear mesh, variations in the actual gear dimensions, and the influence of bearing friction which is partially subtracted but may have velocity-dependent components. Importantly, the ratio of $m_e$ at $45^\circ$ to that at $0^\circ$ is consistently close to 0.5, validating the $\cos^2 \alpha$ dependence inherent to the rack and pinion gear transduction mechanism.

To predict the eddy current damping performance, I conducted a three-dimensional finite element analysis (FEA) using electromagnetic simulation software. The model included the permanent magnets, the copper conductor, the steel back iron, and a surrounding air domain. The key output was the damping torque $T_e$ as a function of the rotor’s angular velocity $\dot{\theta}$. For the linear speed range of our experiments, the relationship was nearly linear, allowing the extraction of a constant rotational damping coefficient $c_\theta$. The equivalent linear damping coefficient $c_e$ for the structure is then $c_e = c_\theta (r_2/(r_1 r_3))^2 \cos^2 \alpha$. The FEA-predicted damping force for a given structural velocity $\dot{u}$ is $F_d = c_e \dot{u}$.

The experimental damping forces were obtained by subtracting the inertial and frictional forces from the total measured force when the magnets were installed. The results for both loading angles are compared with FEA simulations in Table 2. The conductor plate thickness was 2 mm for this set of data.

| Loading Angle $\alpha$ | Structural Velocity Amplitude $\dot{u}_a$ (m/s) | Experimental Damping Force Amplitude $Q_{da}$ (N) | FEA-Simulated Damping Force Amplitude $Q_{da}$ (N) | Relative Error | Experimental $c_e$ (N·s/m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0° | 0.031 | 24.1 | 26.5 | -9.1% | 775 |

| 0.063 | 48.5 | 53.2 | -8.8% | 770 | |

| 0.094 | 72.8 | 79.8 | -8.8% | 774 | |

| 0.126 | 96.5 | 106.5 | -9.4% | 766 | |

| 0.151 | 116.0 | 127.8 | -9.2% | 768 | |

| 45° | 0.031 | 11.9 | 13.3 | -10.5% | 384 |

| 0.063 | 23.8 | 26.6 | -10.5% | 378 | |

| 0.094 | 35.5 | 39.9 | -11.0% | 378 | |

| 0.126 | 47.8 | 53.3 | -10.3% | 379 | |

| 0.151 | 57.5 | 63.9 | -10.0% | 381 |

The agreement between simulation and experiment is satisfactory, with errors around 10%. The slightly lower experimental values may be due to imperfect magnetic circuit closure, minor air gap variations, or temperature effects on conductivity not fully captured in the FEA. The experimental $c_e$ values are stable across velocities, confirming near-linear damping in this range. Furthermore, the ratio of $c_e$ at $45^\circ$ to that at $0^\circ$ is approximately 0.49, again close to the theoretical $\cos^2 45^\circ = 0.5$, demonstrating the consistent scaling law governed by the rack and pinion gear kinematics.

The hysteresis behavior of the ECD-RPG is a critical performance indicator. I conducted tests at a fixed frequency of 0.48 Hz ($\dot{u}_a \approx 0.15$ m/s) and $\alpha=0^\circ$, varying the conductor plate thickness $t_c$ to observe its effect. The complete force-displacement ($F$-$u$) loops, inertial component loops, and damping component loops were analyzed. Representative data for different thicknesses is condensed into Table 3, showing key metrics like energy dissipated per cycle $E_d$ and the equivalent damping ratio $\zeta_e$ for a hypothetical single-degree-of-freedom system.

| Conductor Thickness $t_c$ (mm) | Total Force Amplitude $F_a$ (N) | Inertial Force Amplitude $Q_{ia}$ (N) | Damping Force Amplitude $Q_{da}$ (N) | Energy Dissipated per Cycle $E_d$ (J) | Equivalent Linear Damping Coefficient $c_e$ (N·s/m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 680 | 560 | 120 | 37.7 | 400 |

| 2 | 890 | 767 | 123 | 38.6 | 410 |

| 4 | 1250 | 1120 | 130 | 40.8 | 433 |

| 6 | 1620 | 1490 | 130 | 40.8 | 433 |

| 8 | 1980 | 1850 | 130 | 40.8 | 433 |

The hysteresis loops were consistently smooth and repeatable across all cycles, indicating stable performance with minimal wear or degradation—a direct benefit of the non-contact eddy current damping and the robust rack and pinion gear transmission. As thickness increases, the physical mass $m_c$ and thus the moment of inertia $J$ increase linearly. This causes a significant rise in the inertial force amplitude $Q_{ia}$, as predicted by $m_e \propto J$. The damping force amplitude $Q_{da}$, however, initially increases and then saturates beyond a certain thickness. This saturation occurs because the eddy current penetration depth is limited; beyond a critical thickness, additional material does not contribute significantly to current generation. The energy dissipation $E_d$ per cycle, which is the area enclosed by the damping force-displacement loop, follows a similar trend. This highlights an important design consideration: there exists an optimal conductor thickness for maximizing damping efficiency, beyond which only the apparent mass continues to increase. The rack and pinion gear system effectively transmits both these force components to the structure without modification.

The potential applications for this ECD-RPG are broad. In civil engineering, it could serve as a standalone damper in building frames or bridges, particularly where large inertial forces are beneficial for control, such as in suppressing wind-induced vibrations or seismic responses. Its ability to decompose motion via the orthogonal rack and pinion gear and sliding rail setup makes it suitable for bi-directional control systems. Furthermore, the apparent mass effect can be exploited to design novel tuned mass damper inerter (TMDI) systems, where the large $m_e$ allows for effective tuning with smaller attached physical masses. The non-contact nature ensures long service life and minimal maintenance, addressing key drawbacks of fluid viscous or friction-based dampers.

Future work will involve scaling up the prototype for higher force capacities. Parametric studies will optimize the gear ratios of the rack and pinion gear train, the magnet configuration, and the conductor geometry. Investigating nonlinear effects at higher velocities, where the eddy current damping becomes nonlinear and the rack and pinion gear dynamics might introduce higher-order effects, is also crucial. Additionally, developing accurate closed-form models for the damping torque $T_e(\dot{\theta})$ that account for edge effects and temperature will enhance predictive design.

In conclusion, I have presented a comprehensive study on a novel Eddy Current Damper that utilizes a rack and pinion gear transmission system. The theoretical analysis established that the device produces a force composed of an apparent mass (inertial) term and a damping term, both scalable by the square of the gear ratio and the cosine squared of the loading angle. Experimental results from a prototype confirmed these predictions, showing good agreement with theoretical apparent mass and finite element-simulated damping forces. The hysteresis performance was stable and repeatable. The rack and pinion gear mechanism proved to be the critical enabler, providing the motion conversion and amplification necessary to achieve significant forces from a compact rotational damper. This research demonstrates the feasibility and promising performance of the ECD-RPG as a versatile device for structural vibration control.

The mathematical foundation can be further elaborated. The equations governing the electromagnetic damping are derived from Maxwell’s equations. For a conductor moving with velocity $\vec{v}$ relative to a magnetic field $\vec{B}$, the induced current density $\vec{J}$ is given by Ohm’s law for moving conductors: $\vec{J} = \sigma (\vec{E} + \vec{v} \times \vec{B})$, where $\sigma$ is electrical conductivity. The damping force density is $\vec{f} = \vec{J} \times \vec{B}$. Integrating over the conductor volume gives the total damping force or torque. For a rotational configuration with angular velocity $\dot{\theta}$, a common simplified model for the damping torque is $T_e = k \dot{\theta}$, where $k$ is a constant depending on geometry, magnetic flux, and conductivity. However, more precise models account for magnetic diffusion. The torque can be expressed as:

$$ T_e = \frac{\pi \sigma \omega B_0^2}{2} \int_{r_i}^{R} \int_{0}^{h} \frac{r^3}{1 + (\omega \tau)^2} dr dz $$

where $\omega = \dot{\theta}$ is angular speed, $B_0$ is the characteristic magnetic flux density, $\tau = \mu_0 \sigma \delta^2$ is a magnetic diffusion time constant, $\delta$ is a characteristic dimension, and the integrals are over the radial and thickness dimensions of the conductor. This illustrates the complexity behind the seemingly simple linear relationship observed in the low-speed regime. The rack and pinion gear system’s role is to map the structural linear velocity $\dot{u}$ to this angular velocity $\omega$ via $\omega = (r_2/(r_1 r_3)) \dot{u} \cos \alpha$.

To further illustrate the design space, consider the following generalized equations for the ECD-RPG performance metrics as functions of key rack and pinion gear and electromagnetic parameters:

$$ m_e = \left[ \frac{1}{2} \rho_c \pi (R^2 – r^2) t_c (R^2 + r^2) \right] \cdot \left( \frac{N_2}{N_1 N_3} \right)^2 \cdot \cos^2 \alpha $$

$$ c_e \approx \left[ \frac{\pi \sigma B_{\text{eff}}^2}{2} \cdot f_{\text{geo}}(R, r, t_c, g) \right] \cdot \left( \frac{N_2}{N_1 N_3} \right)^2 \cdot \cos^2 \alpha $$

Here, $\rho_c$ is conductor density, $N_i$ are tooth numbers of the gears (related to radii), $B_{\text{eff}}$ is an effective magnetic flux density in the air gap, $g$ is the air gap size, and $f_{\text{geo}}$ is a complex geometric function. These equations highlight that both key performance metrics are proportional to the square of the overall gear ratio $(N_2/(N_1 N_3))^2$, which is determined by the rack and pinion gear train design. This quadratic dependence provides a powerful means to tailor the damper’s force characteristics without altering the electromagnetic core. For instance, to double the apparent mass, one could increase the gear ratio by a factor of $\sqrt{2}$ by adjusting the number of teeth on the rack and pinion gears, a more practical approach than doubling the physical rotor mass. This underscores the indispensable flexibility afforded by the mechanical rack and pinion gear transmission in this integrated damper system.