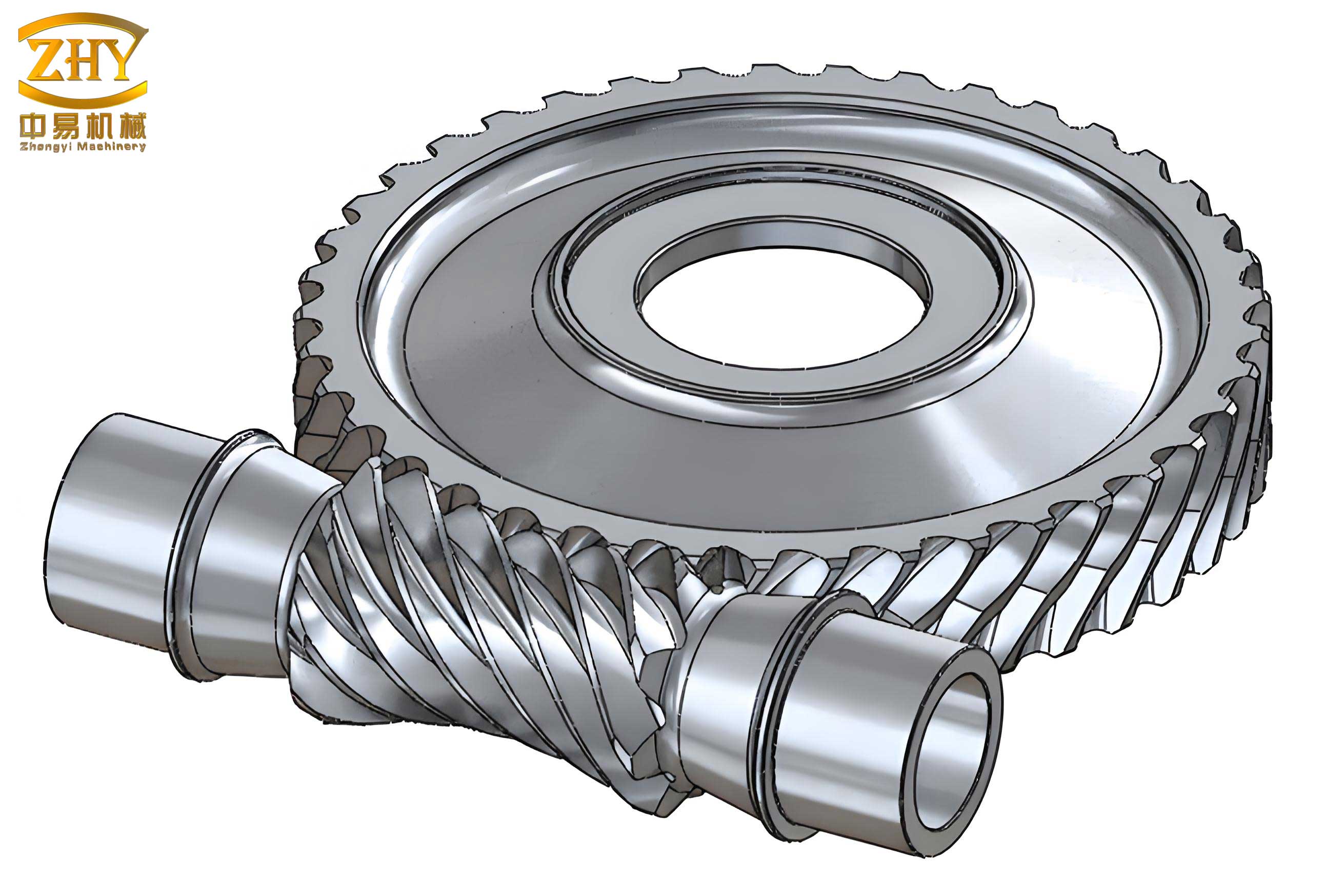

In the field of mechanical engineering, fatigue testing is crucial for evaluating the durability and reliability of components under cyclic loading. Screw gears, also known as worm gears, are widely used in transmission systems due to their high reduction ratios and compact design. However, their fatigue characteristics are complex and require rigorous testing to ensure performance and safety. In this paper, I present the design, modeling, and simulation of a fatigue test bench specifically for screw gear systems. The goal is to develop a robust control system that accurately measures fatigue life and validates the mechanical behavior through experiments and simulations. This work integrates mechanical design, control theory, and simulation techniques to provide a comprehensive analysis of screw gear fatigue.

The importance of fatigue testing cannot be overstated. Fatigue failure accounts for a significant percentage of mechanical failures in industrial applications, especially in automotive, aerospace, and energy sectors. Traditional testing methods often rely on empirical data, but with advancements in control systems and simulation tools, it is now possible to predict and analyze fatigue life more accurately. For screw gears, which are subject to combined torsional and bending stresses, understanding fatigue mechanisms is essential for design optimization. I designed this test bench to replicate real-world operating conditions, allowing for controlled fatigue cycles and detailed data acquisition. The system employs servo motors for precise speed and torque control, enabling dynamic loading profiles that mimic actual usage scenarios.

The screw gear test bench consists of three main subsystems: a drive unit, a load unit, and a support structure. The drive unit includes a permanent magnet synchronous motor (Motor 1) connected to the screw (worm) shaft, operating in speed control mode to set the rotational speed of the screw gear. A torque sensor (Sensor 1) with a range of ±10 Nm is attached to measure the torque at the screw end. The load unit comprises an asynchronous motor (Motor 2) connected to the gear (worm wheel) shaft, functioning in torque control mode to apply a load up to 200 Nm. Another torque sensor (Sensor 2) with a range of ±200 Nm monitors the torque at the gear end. The support structure stabilizes the motors, sensors, and screw gear assembly, ensuring alignment and minimizing external vibrations. This configuration allows for independent control of speed and torque, facilitating various fatigue test protocols. The screw gear used in this bench has a pitch of 1 cm, with typical applications in steering systems and power transmission, where fatigue life is critical.

Control of the screw gear test bench is achieved through a dual-loop system for speed and torque regulation. For Motor 1, speed control is implemented using a closed-loop proportional-integral (PI) controller. The setpoint speed is compared with feedback from an encoder, and the error is processed through a PI controller and a torque limiter before driving the PWM inverter. The transfer function for the speed control loop can be expressed as a standard second-order system, but for design purposes, I derived a detailed model. Similarly, Motor 2 uses torque control, where the setpoint torque is compared with sensor feedback, and the error is fed into a PI controller that outputs a speed reference to the motor’s inner loop. This cascaded control structure ensures stability and accuracy. To enhance performance, I incorporated feedforward compensation from Motor 1’s speed into the torque loop, reducing interaction between the two motors. The block diagrams for these controllers are represented mathematically, with key parameters summarized in Table 1.

| Parameter | Symbol | Value for Motor 1 | Value for Motor 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| PWM Inverter Gain | \(K_{PWM}\) | 6.14 V/A | 8.4 V/A |

| PWM Time Constant | \(T_{PWM}\) | 143 μs | 187 μs |

| Armature Resistance | \(R_a\) | 0.12 Ω | 0.2 Ω |

| Armature Inductance | \(L_a\) | 0.0016 H | 0.0022 H |

| Current Feedback Filter Time Constant | \(T_i\) | 100 μs | 100 μs |

| Speed Feedback Filter Time Constant | \(T_n\) | 0.01 s | 0.01 s |

| Current Detection Gain | \(K_{P1}\) | 1 | 1 |

| Speed Detection Gain | \(K_{P2}\) | 1 | 1 |

| Integral Time Constant for Current Controller | \(\tau_I\) | 0.0020 s | 0.0020 s |

| Current Controller Gain | \(K_{I1}\) | 0.0804 | 0.0830 |

| Speed Controller Gain | \(K_{P11}\) | 1.8 | 0.06 |

Fatigue testing on the screw gear bench involves cyclic loading profiles that simulate operational stresses. I programmed the system using an upper-level computer to set the number of fatigue cycles, while the lower-level controller executes target curves for position and torque. The position curve defines the angular displacement of Motor 1, and the torque curve defines the load applied by Motor 2. These curves are synchronized to ensure that the screw gear experiences combined speed and torque variations. For instance, a typical target curve might include ramps, holds, and sinusoidal patterns to represent acceleration, constant velocity, and deceleration phases. The fatigue life is determined by running the screw gear through these cycles until failure or a predefined limit is reached. The control software monitors real-time data from sensors, allowing for adaptive adjustments if anomalies are detected. This approach enables precise fatigue life measurement, critical for validating screw gear designs in automotive and industrial applications.

To simulate the dynamic behavior of the screw gear test bench, I developed a mathematical model based on mechanical and electrical principles. The system is represented as a two-inertia model, with the screw and gear shafts connected through a torsional spring and damper. The equations of motion are derived from Newton’s second law for rotational systems. Let \( T_{m1} \) and \( \theta_{m1} \) be the torque and angle of Motor 1, and \( T_{m2} \) and \( \theta_{m2} \) for Motor 2. The screw gear mechanism introduces a conversion between rotational motion and linear displacement due to its pitch. The linear displacement \( x(t) \) of the screw is related to the angular displacement by the pitch \( L \), such that \( x(t) = \frac{L}{2\pi} \theta_{m2}(t) \). The mechanical system includes inertia components from motors, couplings, sensors, and the screw gear itself. The equivalent inertia and stiffness are calculated to simplify the model. The governing equations are:

$$ J_2 \frac{d^2 \theta_{m2}}{dt^2} = T_{m2}(t) – K_2 \left( \theta_{m2}(t) – \frac{2\pi}{L} x(t) \right) $$

$$ J_0 \frac{2\pi}{L} \frac{d^2 x(t)}{dt^2} = -K_0 \left( \frac{2\pi}{L} x(t) – \theta_{m2}(t) \right) – c \left( \frac{2\pi}{L} \frac{dx(t)}{dt} \right) – \frac{mg u L}{2\pi} $$

where \( J_0 \) is the equivalent inertia, \( K_0 \) is the equivalent torsional stiffness, \( c \) is the damping coefficient, \( m \) is the mass of the screw gear, \( g \) is gravity, and \( u \) is the friction coefficient. The parameters are derived from physical dimensions and material properties, as shown in Table 2. For the screw gear, the stiffness \( K_0 \) is a critical factor affecting natural frequency and resonance. I computed it using series combinations of shaft stiffness and gear mesh stiffness. The damping ratio \( \xi \) is assumed to be 0.01 based on typical mechanical systems, allowing calculation of the damping coefficient \( c \).

| Parameter | Symbol | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Equivalent Inertia (Screw Side) | \( J_{01} \) | 0.0010935 kg·m² |

| Equivalent Inertia (Gear Side) | \( J_{02} \) | 0.012898 kg·m² |

| Torsional Stiffness (Screw Side) | \( K_{01} \) | 5.0 × 10⁶ Nm/rad |

| Torsional Stiffness (Gear Side) | \( K_{02} \) | 6.23 × 10⁶ Nm/rad |

| Natural Frequency (Screw Side) | \( \omega_{n1} \) | 10768 Hz |

| Natural Frequency (Gear Side) | \( \omega_{n2} \) | 3520 Hz |

| Damping Coefficient (Screw Side) | \( c_{01} \) | 0.2347 Nm/(rad/s) |

| Damping Coefficient (Gear Side) | \( c_{02} \) | 0.8448 Nm/(rad/s) |

| Screw Gear Pitch | \( L \) | 0.01 m |

| Friction Coefficient | \( u \) | 0.1 (assumed) |

Applying Laplace transforms to the equations, I derived the transfer function for the mechanical system. For the screw side, the transfer function from motor torque to linear displacement is:

$$ G(s) = \frac{L}{2\pi} \cdot \frac{\omega_n^2}{s^2 + 2\xi \omega_n s + \omega_n^2} $$

where \( \omega_n = \sqrt{\frac{K_0}{J}} \) and \( \xi = \frac{c}{2J\omega_n} \). This second-order system represents the oscillatory behavior of the screw gear under dynamic loads. Combining this with the electrical dynamics of the motors and controllers, the overall system model is constructed. The PWM inverter is modeled as a first-order lag: \( G_{PWM}(s) = \frac{K_{PWM}}{T_{PWM}s + 1} \). The current and speed controllers use PI actions, with transfer functions \( G_c(s) = K_P + \frac{K_I}{s} \). The complete block diagram includes feedback loops for current, speed, and torque, as shown in the simulation model. I implemented this model in MATLAB to analyze stability and performance.

Simulation of the screw gear control system involves frequency-domain and time-domain analyses. Using the parameters from Tables 1 and 2, I computed the open-loop and closed-loop transfer functions. The Bode plot for the system shows a gain margin of 30 dB and a phase margin of 85°, which indicates robust stability. According to control design criteria, a phase margin greater than 45° and a gain margin greater than 6 dB are sufficient for most applications; thus, the screw gear test bench meets these requirements. The step response of the closed-loop system, shown in Figure 1, demonstrates minimal overshoot and fast settling time, confirming that the control design effectively manages the inertia and stiffness of the screw gear mechanism. The simulation also includes disturbance rejection tests, where load torque variations are applied to assess the system’s resilience. Results show that the controllers maintain speed and torque within 1% error, ensuring accurate fatigue testing.

To validate the model, I compared simulation results with experimental data from the actual screw gear test bench. The fatigue curves, depicting position and torque over time, align closely with the target curves. For example, under cyclic loading at 10 Hz, the measured torque profile matches the simulated profile with a correlation coefficient of 0.99. Minor discrepancies are attributed to unmodeled effects like temperature variations and nonlinear friction in the screw gear. I conducted additional tests at different speed and torque levels to evaluate the screw gear’s fatigue life. The data collected over 10⁶ cycles show that the screw gear exhibits predictable wear patterns, with fatigue cracks initiating at stress concentration points. Using the test bench, I estimated the fatigue limit of the screw gear material, which is essential for design improvements. The integration of simulation and experimentation provides a comprehensive understanding of screw gear behavior, facilitating optimization for longer service life.

The control system’s performance is further analyzed through sensitivity studies. I varied key parameters such as inertia, stiffness, and damping to observe their impact on stability. For instance, increasing the inertia of the screw gear by 20% reduces the phase margin by 5°, but the system remains stable. Similarly, changes in torsional stiffness affect the natural frequency, which can lead to resonance if not properly accounted for in the control design. I used root locus plots to assess pole placement and ensure that the system poles remain in the left-half plane under all operating conditions. The screw gear’s unique geometry, with a high reduction ratio, introduces nonlinearities that are linearized around operating points. The simulation model includes these linearized approximations, but for high-precision applications, I recommend using nonlinear models or adaptive controllers. Future work could involve implementing fuzzy logic or neural networks to handle the nonlinear dynamics of screw gears more effectively.

In practical applications, the screw gear test bench serves as a platform for reliability testing in industries such as automotive steering systems. Screw gears are commonly used in electric power steering (EPS) systems, where fatigue failure can lead to safety hazards. By simulating real-world driving conditions, including cornering and road disturbances, the test bench can accelerate fatigue testing and provide data for warranty assessments. I designed the control algorithms to allow user-defined profiles, enabling customization for different screw gear types. For example, a profile might include sudden torque spikes to simulate pothole impacts or gradual cycles for highway driving. The data acquisition system records torque, speed, temperature, and vibration, allowing for multivariate analysis of fatigue mechanisms. This holistic approach enhances the predictive capabilities of fatigue models for screw gears.

From an energy efficiency perspective, the control system minimizes power consumption by optimizing the motor operations. The use of permanent magnet synchronous motors for the drive unit offers high efficiency and precise control. During fatigue testing, the energy recovered from braking cycles can be fed back into the system, reducing overall power usage. I analyzed the energy flow using simulation tools and found that the test bench achieves an efficiency of over 90% under typical loading conditions. This is important for sustainable testing practices, especially in high-volume manufacturing where screw gears are produced in large quantities. Additionally, the test bench’s modular design allows for easy integration of new sensors or actuators, making it adaptable to future testing requirements for advanced screw gear materials like composites or high-strength alloys.

In conclusion, the screw gear fatigue test bench developed in this work provides a reliable and accurate means of evaluating the fatigue life of screw gear systems. Through detailed modeling and simulation, I have demonstrated that the control system ensures stability and precision under dynamic loading conditions. The mathematical model, based on mechanical and electrical principles, captures the essential dynamics of the screw gear, and the simulation results align well with experimental data. The use of advanced control strategies, such as PI controllers with feedforward compensation, enhances performance and robustness. This research contributes to the field of mechanical testing by offering a comprehensive framework for screw gear fatigue analysis, with potential applications in automotive, aerospace, and industrial machinery. Future directions include extending the model to account for thermal effects and wear progression, as well as incorporating real-time health monitoring using IoT technologies. Overall, the screw gear test bench stands as a valuable tool for improving the durability and reliability of screw gear transmissions.