In my experience with the FT624 vertical slice cutting machine, a critical component in the tobacco primary processing line, I have encountered persistent issues affecting production stability. This machine, comprising a frame, pusher car, conveyor belt, cutter head, flipping device, blocking plate device, guiding device, and compressed air system, is designed to precisely cut tobacco bales into uniform slices. However, a design flaw in the transmission mechanism of the blocking plate device led to inconsistent slice thickness and overlapping tobacco blocks. These irregularities caused flow instability in the subsequent loosening and conditioning process, frequently resulting in blockages and material breaks, thereby compromising process quality control. My investigation focused on the root cause and the implementation of a robust solution centered on the application of screw gears.

The core problem manifested during operation: as the pusher car advanced the tobacco bale, it exerted a significant impact force against the blocking plate. The plate’s positioning mechanism, driven by a standard gear reducer, lacked a self-locking capability. Consequently, the impact force caused the blocking plate to shift backward. This displacement altered the effective cutting position for each slice, leading to variations in thickness. Thicker slices would not slide down smoothly, while thinner slices, especially the final irregularly shaped piece with a forward center of gravity, would follow the preceding slice and overlap onto it. This stacking phenomenon was exacerbated when processing loose or thin-leaf tobacco. The accumulated, non-uniform material flow onto the conveyor belt directly contributed to choke-ups and breaks at the inlet of the loosening and conditioning cylinder. To quantify the instability, the standard deviation of slice width was measured at 11.5 cm prior to any modifications.

A fundamental mechanical analysis clarifies the issue. The force exerted by the tobacco bale on the blocking plate can be described by the impulse-momentum principle. The change in momentum of the bale during deceleration creates an impulse on the plate. If the resisting torque from the reducer’s output shaft is insufficient, the plate rotates and retracts. The relationship can be simplified for analysis. Let the mass of the tobacco bale be \( m_b \), its velocity at contact be \( v \), and the effective deceleration distance be \( s \). The average impact force \( F_{impact} \) can be approximated as:

$$ F_{impact} \approx \frac{m_b v^2}{2s} $$

This force creates a torque \( \tau_{impact} \) on the blocking plate mechanism at a radius \( r \):

$$ \tau_{impact} = F_{impact} \cdot r $$

The original gear reducer, with a transmission ratio \( i_{gear} = 37 \), provides an output torque \( \tau_{output} \) related to the motor torque \( \tau_{motor} \) and efficiency \( \eta_{gear} \):

$$ \tau_{output, gear} = \tau_{motor} \cdot i_{gear} \cdot \eta_{gear} $$

However, the critical factor is the reducer’s ability to resist back-driving. A standard parallel-axis gear reducer has high efficiency in both directions, meaning a torque applied to the output shaft can easily back-drive the input motor (i.e., it lacks self-locking). Therefore, when \( \tau_{impact} \) exceeds the frictional and motor holding torque, the plate moves. The condition for stability is:

$$ \tau_{resisting} > \tau_{impact} $$

Where \( \tau_{resisting} \) is the net torque preventing backward rotation. For the original system, \( \tau_{resisting} \) was too low.

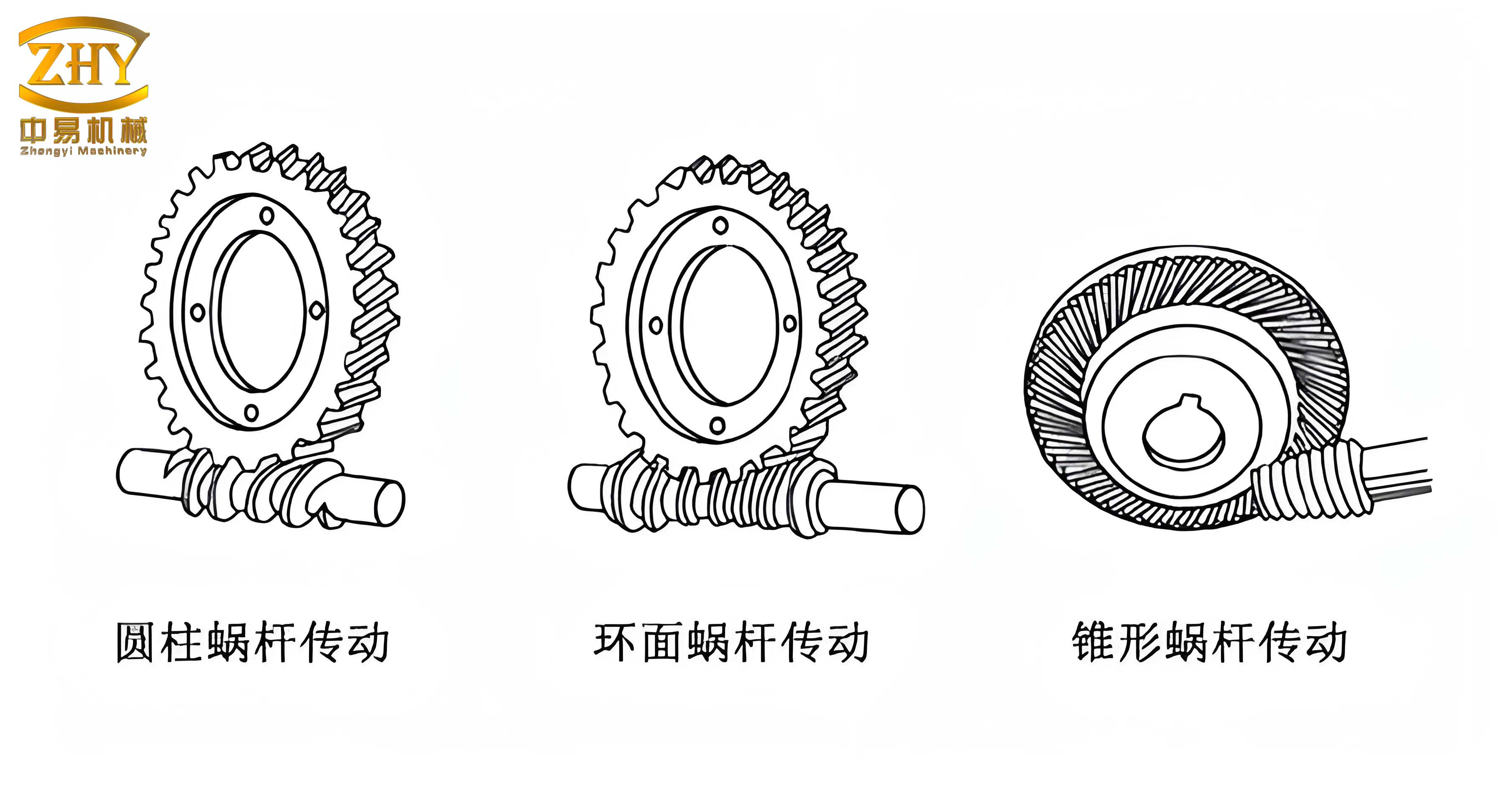

The pivotal improvement involved replacing the standard gear reducer with a screw gears system, specifically a worm gear reducer. Screw gears, characterized by a worm (screw) meshing with a worm wheel, offer a quintessential advantage: inherent self-locking under certain conditions. This property arises from the high friction and the lead angle of the worm. If the lead angle \( \lambda \) is less than the arctangent of the coefficient of friction \( \mu \), the mechanism becomes self-locking, preventing output back-driving. The condition is:

$$ \lambda < \tan^{-1}(\mu) $$

This fundamental principle of screw gears makes them ideal for applications requiring a rigid positional hold, such as the blocking plate. Furthermore, screw gears provide significantly larger single-stage reduction ratios compared to parallel shaft gears, allowing for more compact designs to achieve the necessary slow output speed for precise plate adjustment.

The following table contrasts the key characteristics of the original gear reducer and the proposed screw gears system:

| Parameter | Original Gear Reducer | Screw Gears (Worm Gear Reducer) |

|---|---|---|

| Self-locking Capability | No | Yes (when \( \lambda < \tan^{-1}(\mu) \)) |

| Typical Single-Stage Ratio Range | 1:1 to 1:10 (higher with multi-stage) | 1:10 to 1:100+ |

| Mechanical Efficiency | High (95-98%) | Moderate to Low (50-90%), depends on ratio and design |

| Back-drive Efficiency | High | Very Low to Zero (when self-locking) |

| Compactness for given ratio | Less compact for high ratios | Very compact for high ratios |

| Primary Application | Power transmission, speed reduction | Speed reduction, positioning, holding loads |

For the FT624 machine, the self-locking property of screw gears was the paramount selection criterion. The original reducer had an output speed of 39 rpm, derived from a 1440 rpm motor and a 1:37 ratio. To maintain the same operational cycle time and plate adjustment speed after retrofit, the output speed needed to remain constant. The selected screw gears unit had a standard ratio of \( i_{screw} = 50 \). Its theoretical output speed with the same motor would be:

$$ N_{out, screw\_theory} = \frac{N_{motor}}{i_{screw}} = \frac{1440}{50} = 28.8 \, \text{rpm} $$

To compensate and restore the output speed to the original 39 rpm, the drive pulley system between the motor and the screw gears input shaft was modified. The speed relationship in a belt drive is governed by:

$$ \frac{N_{driver}}{N_{driven}} = \frac{D_{driven}}{D_{driver}} $$

Let the original setup be: Motor pulley diameter \( D_{m,old} \), reducer input pulley diameter \( D_{in,old} \), and reducer output pulley diameter \( D_{out,old} = 100 \, \text{mm} \). The original output speed was 39 rpm. For the new setup with screw gears, we need \( N_{out,new} = 39 \, \text{rpm} \). Given the screw gears’ theoretical output speed is 28.8 rpm, the diameter of the new output pulley \( D_{out,new} \) on the screw gears must be increased to achieve a higher linear speed at the same rotational speed. The required ratio for the output stage is:

$$ \frac{D_{out,new}}{D_{out,old}} = \frac{N_{out,old}}{N_{out,screw\_theory}} $$

Therefore,

$$ D_{out,new} = D_{out,old} \cdot \frac{N_{out,old}}{N_{out,screw\_theory}} = 100 \, \text{mm} \cdot \frac{39}{28.8} \approx 135.4 \, \text{mm} \approx 135 \, \text{mm} $$

Furthermore, to accommodate the physical dimensions of the new screw gears unit and motor, the primary drive stage was also recalculated. The new motor pulley diameter was chosen as \( D_{m,new} = 97 \, \text{mm} \), and the new screw gears input pulley diameter as \( D_{in,new} = 71 \, \text{mm} \). The center distance \( C \) between these two shafts was measured as 130 mm after installation. The required belt length \( L \) for a two-pulley system can be approximated by:

$$ L \approx 2C + \frac{\pi}{2}(D_{m,new} + D_{in,new}) + \frac{(D_{m,new} – D_{in,new})^2}{4C} $$

Substituting the values:

$$ L \approx 2 \times 130 + \frac{\pi}{2}(97+71) + \frac{(97-71)^2}{4 \times 130} $$

$$ L \approx 260 + \frac{\pi}{2} \times 168 + \frac{676}{520} $$

$$ L \approx 260 + 263.9 + 1.3 \approx 525.2 \, \text{mm} $$

A standard A-section V-belt of type A-600 (inside length ~605 mm, effective length ~600 mm accounting for pitch line differences) was suitable. The installation involved drilling new mounting holes adjacent to the original reducer’s position to fix the screw gears housing and realigning the motor. The original synchronous belt connecting the reducer output to the blocking plate mechanism was retained, as the new 135 mm output pulley maintained the necessary timing.

The following table summarizes the key parameters before and after the screw gears retrofit:

| Component/Parameter | Original Configuration | Modified Configuration with Screw Gears |

|---|---|---|

| Blocking Plate Reducer Type | Parallel Shaft Gear Reducer | Worm Gear Reducer (Screw Gears) |

| Reducer Transmission Ratio | 1:37 | 1:50 |

| Motor Speed (rpm) | 1440 | 1440 |

| Theoretical Reducer Output Speed (rpm) | 38.9 (1440/37) | 28.8 (1440/50) |

| Output Pulley Diameter (mm) | 100 | 135 |

| Final Output Speed at Blocking Plate (rpm) | ~39 | ~39 (via pulley compensation) |

| Motor Pulley Diameter (mm) | Not specified (part of integrated unit) | 97 |

| Reducer Input Pulley Diameter (mm) | Not specified | 71 |

| Drive Belt Type (Motor to Reducer) | Integrated | A-600 V-belt |

| Center Distance, Motor to Reducer (mm) | Fixed | 130 |

| Self-locking Property | No | Yes |

The effectiveness of incorporating screw gears was immediately apparent and quantitatively verifiable. Post-modification, continuous monitoring confirmed that the blocking plate remained steadfast upon impact from the tobacco bale. The self-locking nature of the screw gears completely eliminated the backward shift, ensuring a consistent and reliable cutting reference position for every slice. This directly translated into superior slice uniformity. Statistical process control data showed a marked reduction in slice width variation. The standard deviation of slice width improved from the initial 11.5 cm to 9.4 cm after the retrofit. This 18.3% reduction in variability is significant for process stability.

To further analyze the torque holding capability, we can model the system. With screw gears, the holding torque \( \tau_{hold} \) against back-driving is immense due to the self-locking condition. The efficiency for back-driving \( \eta_{back} \) is near zero. Therefore, the resisting torque available is essentially the breakaway torque of the screw gears system, which is a function of the input shaft holding torque (provided by the motor brake or friction) multiplied by the very high reverse mechanical advantage. For a worm gear with lead angle \( \lambda \), normal pressure angle \( \alpha_n \), and coefficient of friction \( \mu \), the efficiency for driving from worm to wheel \( \eta_d \) is:

$$ \eta_d = \frac{\cos \alpha_n – \mu \tan \lambda}{\cos \alpha_n + \mu \cot \lambda} $$

The efficiency for back-driving (wheel to worm) \( \eta_b \) is:

$$ \eta_b = \frac{\cos \alpha_n \tan \lambda – \mu}{\cos \alpha_n + \mu \tan \lambda} $$

When \( \eta_b \leq 0 \), self-locking occurs. In our application, the selected screw gears were specifically chosen to satisfy this condition robustly, ensuring \( \tau_{impact} < \tau_{hold} \).

The improvement in material flow was dramatic and visually evident in the process data trends. Before the screw gears retrofit, the flow rate at the inlet to the loosening and conditioning stage showed frequent spikes and dips corresponding to blockages and breaks, indicating the inconsistent feed of overlapping and variably thick slices. After the retrofit, the flow rate stabilized significantly, exhibiting a much smoother and consistent profile. This directly addressed the core issue of “blockage” and “breakage,” enhancing overall line efficiency and product quality consistency. The reduction in manual interventions to clear jams also lowered operator workload.

Beyond the immediate application, the principles of using screw gears for positional integrity extend to numerous other machine elements in tobacco processing and beyond. For instance, gate controls, adjustable guides, and indexing mechanisms that require holding against intermittent forces can benefit from the self-locking characteristic of screw gears. The design calculations also underscore the importance of system-level integration—simply swapping a reducer is insufficient; one must recalibrate the entire drive train (e.g., pulley sizes) to preserve functional parameters like speed. The screw gears solution proved to be a cost-effective and reliable modification because it addressed the root cause (lack of self-locking) with a standard, durable mechanical component.

In conclusion, the strategic replacement of a standard gear reducer with a self-locking screw gears system in the FT624 vertical slice cutting machine’s blocking plate mechanism resolved a chronic production issue. The inherent back-drive resistance of screw gears provided the necessary rigidity to withstand impact forces, ensuring consistent slice thickness and preventing tobacco block overlap. This mechanical fix, complemented by precise pulley recalculation, resulted in an 18.3% reduction in slice width variability and eliminated downstream flow disruptions. The success of this project highlights the critical importance of selecting power transmission components not just for their speed reduction capabilities, but for their dynamic holding properties in applications involving shock loads or positional accuracy. Screw gears, with their unique combination of high reduction ratio and self-locking, offer an invaluable solution for enhancing stability in industrial machinery where precise positioning under load is paramount. Future designs of similar equipment should strongly consider incorporating screw gears from the outset for critical positioning functions to ensure inherent process robustness and reduce maintenance needs. The reliability and simplicity of the screw gears mechanism make it a cornerstone for improving mechanical stability in demanding industrial environments.